Slumberland Review: Dream On, Film Off

- Heartfelt themes

- Strong performances

- Feels only tenuously connected to the source material

- Dream world doesn't feel particularly inventive

In a world where a majority of new films in the marketplace must be based in some way on existing IP, it is strange to find a film so divorced from its source material. Take Netflix's new film "Slumberland." 20 or so minutes into this very expensive, very schmaltzy family film, the viewer might find themselves scratching their heads to figure out what recently published YA novel this picture has taken a stab at adapting. But a cursory google search will reveal that this is in fact an adaptation of Winsor McCay's iconic "Little Nemo" comic strip from the early 20th century. One of the most influential and enduring examples of sequential art ever drafted, reduced to what is sure to be a forgettable streaming release aimed at kids whose grandparents might not even recall its origins.

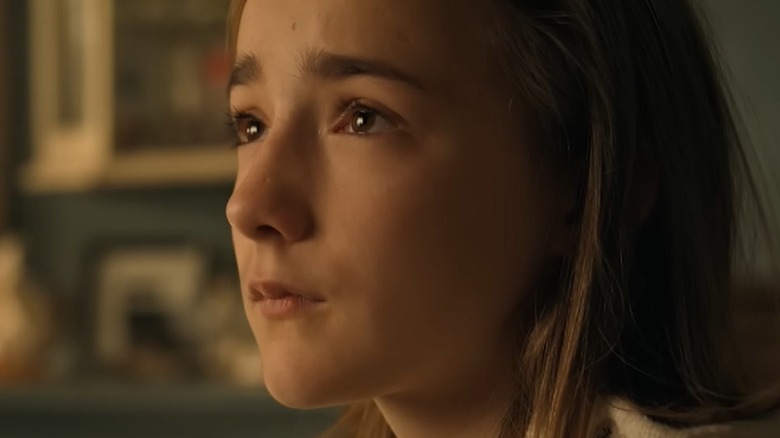

That's not to say "Slumberland" possesses no redeeming qualities. The film follows a gender-swapped Nemo (Marlow Barkley) as she navigates the world of dreams in the hopes of being reconnected with her deceased father (Kyle Chandler). Director Francis Lawrence seems to be having a good time balancing the story's tearjerker elements with its more whimsical and fantastical visual flourishes, and he's got a game cast at his disposal, including Jason Momoa as Nemo's dreamland companion Flip and Chris O'Dowd as her uncle and new caretaker Philip.

But for all the heartfelt moments "Slumberland" nails with relative ease, one can't help but feel let down by the chasm between how imaginative McCay's awe-inspiring illustrations remain and how screensaver bland the final looks by comparison.

The adventure begins

When we meet little Nemo (Barkley), her world is incredibly small. She lives in a lighthouse with her father Peter (Chandler), a man who alleges to have lived an illustrious life full of adventure and intrigue. His riveting bedtime stories provide enough nourishment for Nemo to never want for a world bigger or more expansive than the one she knows. The swashbuckling intensity of her dad's tall tales is more than enough excitement for this little girl and her lighthouse-keeper aspirations. But when Peter is lost at sea and she's shipped away to live with his doddering, emotionally closed-off brother Philip (O'Dowd), she can't fathom a life without him.

Her dreams become more lifelike, and within them, she meets Flip (Momoa), a horned outlaw who purports to be her father's former partner from his old life. Flip enlists Nemo's help in procuring mythical pearls deep in the heart of Slumberland, the dream world, that provide wishes, giving her the hope of seeing her father again.

When "Slumberland" works, it's as a fable about the power of childlike wonderment. The heart of Nemo's relationship with her father lies in their shared ability to invest in the impossible, to dream, and fixate on the unlimited potential of magical thinking. When Nemo loses him, she fears she'll lose her connection to that raw conduit of possibility. This is exacerbated by the time she spends with Philip, an introverted doorknob company employee who seems to only be excited by living in a high-rise apartment building he seldom has to leave. He's the polar opposite of Peter in every imaginable way, and as much as Nemo doesn't want to spend the rest of her adolescence with him as a young ward, she also doesn't want to grow up to be like him, ever.

So her kinship with the impish and chaotic rogue Flip, and his tenuous connection to her father, just makes more sense. There's something a little doomed in her pursuit of this pearl, as she goes from thinking it can bring her father back to life to planning to live forever in a dream where he's still alive, never having to wake up or grow old. It's heartbreaking, in a way, to see a child so ready to give up on existence for a little more time in a fantasy. By the film's halfway mark, even the audience may have difficulty supporting this quest, but that's conveniently where the film reveals something important about Flip and his true nature, a devastating but not entirely un-telegraphed twist that reshapes the remainder of the film's plot.

It more squarely shapes "Slumberland" from a story about grieving a lost loved one to a story about the death of the inner child, of the inevitable march of time, and the cruel way it sands the entertaining edges off of existence itself. For that thematic throughline, "Slumberland" is a moving and rewarding picture — one that feels a little like Steven Spielberg's underrated Peter Pan flick "Hook." But it's not adapted from J.M. Barrie's public domain classic. It's based on something it otherwise feels so detached from.

Little Nemo's origins

In adapting McCay's "Little Nemo" strips, it feels as though director Francis Lawrence and the film's screenwriters David Guion and Michael Handelman took some character names and the generic premise of "Slumberland" — an alternative world in which all dreams are connected — and found their own story to tell. This is fine, obviously, in the annals of cinematic adaptation, and not necessarily something to angrily underline in red ink. But so much of the appeal those strips have to this day comes from the enigmatic and everlasting ways McCay depicted dreams with his art. The panel progressions and page breakdowns of his strips feel decades ahead of their time on the printed page, and his work in animation predates Walt Disney and the Fleischers in its smoothness and wonder.

So the prospect of watching a blockbuster-budgeted adaptation of his work for a streaming platform where the most eye-catching sequences look, at best, like commercials for a new Apple wearable product and, at worst, like a Maroon 5 video, feels almost insulting. Lawrence is an accomplished enough director, between his work in the music video medium to the "Hunger Games" sequels he brought to life. But whether it's a script more concerned with emotions than spectacle, or if he himself just wasn't inspired enough by the material, the dreamscapes feel so flat and lifeless and uninteresting. People mocked Christopher Nolan for "Inception" being too sterile and industrial to truly capture the enigma of dreams, but at least it possessed an aesthetic that made sense for that filmmaker and their perspective. "Slumberland" feels like its entire production design team threw everything together at the last minute, or left devices to some AI art program.

The strips play in the middle ground between a fairy tale buoyancy and a sort of semi-realistic bureaucratic take on the structure of the dream world, something maybe Terry Gilliam would have had a field day with. But outside of the concept of dream police and a few half-hearted car chases, "Slumberland" could just as easily have taken place in any other ill-defined fantasy land from some similar comic, video game, or yes, even a YA novel.

It also, for all the expanse of its scope, comes off decidedly myopic. A very small ensemble cast and a paucity of variation in the different dreams we're subjected to make everything look and feel so dull, lifeless, and limited. That's a shame given how much heart its cast puts into the film's overarching story.

The best dreams stick with us well into the afternoon of our waking hours, the sensory depth of the emotion outlasting the details or particulars of the dream itself. In that way, the power of its stirring finale lingers longer than the rest of "Slumberland," a film that evaporates into the air once the credits begin to roll.