Classic Movie Scenes Filmed In Just One Take

"They did that in one take" is always an impressive statement to make about any film, but it actually carries two different meanings. On one hand, getting a scene down in a single take can mean everyone involved experienced a moment of genius, perfect execution, or just pure dumb luck, and the scene was completed on the first try. On the other, it can also mean that actors and crew members went over an elaborate sequence any number of times, practicing every line and every camera movement until they were able to execute a gorgeous sequence with a single unbroken shot. The two have very different meanings for the people making the film, but in both cases they produce movie magic for the audience. Here are some of the best examples of both versions of one-take magic, from perfectly choreographed tracking shots to an iconic song recorded perfectly on the first try.

Goodfellas (1990)

The films of Martin Scorsese are absolutely loaded with iconic shots, but few are as well-remembered as this gorgeous long take from Goodfellas. Known to many film fans as "The Copa Shot," it's a nearly three-minute Steadicam take that follows Henry (Ray Liotta) and Karen (Lorraine Bracco) as they enter the Copacabana nightclub through a side entrance so Henry can flaunt his many mob-based connections.

According to camera operator Larry McConkey, the shot was originally just a simple case of the camera following the actors, but he and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus decided to spice up the blocking — in part because McConkey needed pauses in the walk so he could transition between wide shots and close-ups without cutting away — so they added touches like a walk through the club's kitchen (because Ballhaus liked the lighting in there) and the moment when Henry stops to playfully chastise a flirting couple. Add in Scorsese's use of The Crystals' "Then He Kissed Me" on the soundtrack, and you've got a classic moment.

Rope (1948)

Movies like Russian Ark (2002) and Birdman (2014) have taken the idea of the "one-take" film to new heights in the 21st century. Back in the 1940s, though, feature filmmakers were largely uninterested in the idea of trying to make a film even look like it was one continuously flowing shot, let alone actually shooting one that way. Alfred Hitchcock was not like most filmmakers, and decided to stretch the long-take as far as 1940s filmmaking could take him with Rope.

Because the film was based on a stage play that takes place in a single apartment, Hitchcock opted to shoot it as a string of 10-minute takes (roughly the length of a magazine of film at the time) cut together through conveniently timed obstructions of the camera lens (a close-up of someone's back, for example, or the lid of a trunk opening). He hoped that by doing this, he would not only achieve a visually interesting style with a constantly fluid camera, but also end up saving time and money by not resetting over and over for new shots.

That didn't end up working out. Hitchcock had to reshoot a sizable chunk of Rope when he discovered that the backdrop he'd had built for the set — meant to depict a setting sun in real time — was distorted in the first developed film, among other production issues. Ultimately, Rope was neither cost-effective nor a box office hit for Hitchcock, but it remains a fascinating filmmaking experiment.

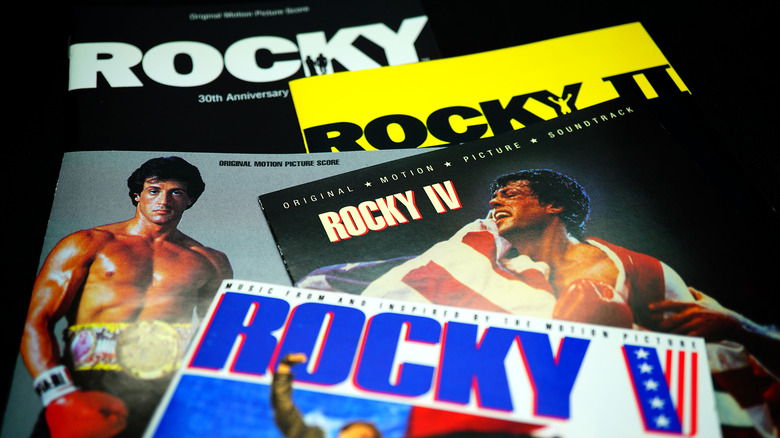

Rocky (1976)

Sometimes films require a single uninterrupted long take. Sometimes they just require a single take, period. In one of Rocky's most emotional scenes, the latter was the case.

The night before his fight with Apollo Creed, Rocky (Sylvester Stallone) goes to Madison Square Garden, where he stands under a massive portrait of his champion opponent. After the bright lights and grand stage really start to get to him, he goes home to his girlfriend Adrian (Talia Shire) and admits all of his fears and doubts while lying in bed next to her. The "I can't beat him" scene is a classic, but it almost didn't happen.

Producers, concerned about the film's schedule, wanted to simply skip the moment, but Stallone (who also wrote the film) fought to keep it in. He managed to convince them to shoot one take, which is what you see in the film. The story goes that he was so nervous about blowing his one shot at the scene that he got drunk before filming. Drunk or not, it's a good thing Stallone nailed the take, because it adds a layer of vulnerability to Rocky that changes the tone of the film's thrilling final act.

Creed (2015)

Nearly 40 years after Rocky, another film in the franchise delivered an iconic moment — not with a single make-or-break take, but with a dazzling, uninterrupted fight sequence. For the fight between Adonis "Donnie" Johnson (Michael B. Jordan) and Leo "The Lion" Sporino (Gabriel Rosado), director Ryan Coogler wanted to achieve the visual metaphor of the two boxers being suddenly "all on their own" within the tight confines of the ring after months of working with their trainers, so the fight was filmed as one continuous Steadicam take, with the camera dancing around the actors.

Coogler shot 13 takes of the fight, with no additional cameras on set to provide extra coverage should he later decide to break it up in the editing room. As he told the New York Times, "We just dove off the cliff and said, hey, we're doing to do this." The result is an intense, intimate sequence that ranks among the best moments in boxing cinema since Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull 35 years earlier.

Children of Men (2006)

Though the stunning opening sequence of his 2013 hit Gravity might be his crowning achievement in long takes, the acclaimed car attack scene in Children of Men is arguably director Alfonso Cuarón's most visceral use of an unbroken visual thread to achieve an emotional impact.

Shot with a special rig that allowed the camera to move around within the cramped car (as well as move out of it later), the four-minute sequence has a lot of moving parts. There's the car itself, packed tight with five actors, a burning car that blocks their path, the extras functioning as any angry mob, a motorcycle crash, a gunshot wound that has to continuously bleed, a police pursuit, and more. To make things even more stressful, Cuarón revealed during a 2013 San Diego Comic-Con panel that a number of circumstances meant he only had approximately four takes to get the shot right. It ended up coming down to the very last take before the production was going to lose access to the location, and Cuarón almost ruined that one himself.

"We were shooting the last take, everything goes great, but then by accident the blood spills onto the lens," he recalled. "I yelled cut, but there was an explosion and nobody heard me so they kept shooting. Then, later, I realized that the blood splash was the miracle [in that scene]."

The final take, the one Cuarón almost abandoned mid-shot, is the one in the film.

The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)

James Bond films are filled with massive action set pieces and daring stunts (particularly in the pre-CGI days), but almost any list of the top five Bond stunts ever performed has to include the corkscrew jump from The Man with the Golden Gun. In the scene, Bond (Roger Moore) is pursuing the titular villain (Christopher Lee) in a car chase, only to find that his prey is on the opposite side of a Thailand river. To fix that, Bond uses a broken bridge to jump an AMC Hornet (stolen from a car showroom in Bangkok) over the water.

In the film, it just looks like Bond did something cool. In reality, it was stuntman Loren "Bumps" Willard who had to execute the daring corkscrew jump. To minimize risk, the production turned to Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory and its Highway Vehicle Object Simulation Model, a computer program designed to increase road safety. The computer model calculated the best speed with which to approach the jump given the off-kilter design of the bridge, but producers still had paramedics on standby just in case. Willard nailed the jump in just one take, and got a £30,000 bonus for his trouble. It's still one of the most recognizable movie stunts ever filmed, despite the annoying slide whistle added to the soundtrack.

The Player (1992)

Robert Altman was one of the most famously playful directors of the 20th century. His movies are packed with improvisation, stepped-on dialogue, and homages, making for films that only get richer with repeat viewing. The Player, a dark satire about a ruthless Hollywood executive, is essentially a movie about movies, so Altman took every chance possible to cram in references to classic films. He also took the opportunity to give us the entire look and feel of the film in an unbroken, eight-minute opening shot.

Beginning with the tongue-in-cheek clicking of a film slate and a call of "Action!" (to remind us we're about to watch a movie about movies), the take pulls back and rises up into a wide crane shot in an homage to Touch of Evil. Then the camera dances around the lot, following various characters as they walk between buildings and peeking in windows to witness meetings the titular power player Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) is having. To further drive the point home, Altman has studio security head Walter Stuckel (Fred Ward) constantly referencing classic Hollywood long takes, including Touch of Evil and Rope, while decrying the "cut, cut, cut" style of filmmaking in the early '90s. Even if you're a true movie buff, it'll take you a few tries to catch every reference and inside joke in the sequence.

Beauty and the Beast (1991)

One-take wonders don't always have to include visuals. Audio recording can sometimes be just as miraculous, and this was the case during recording sessions for Disney's classic animated musical Beauty and the Beast.

Though Celine Dion and Peabo Bryson recorded the title song for a radio release, fans of the film will never forget the emotional vocal performance by Angela Lansbury, singing as Mrs. Potts while Belle and the Beast dance in a grand ballroom. It's hard to imagine now, but according to Lansbury, she was initially reluctant to sing the song at all, believing the style in which it was written didn't really match her particular musical theater background. When she was given permission to interpret the song however she liked, she agreed, but things got more complicated when a bomb scare delayed her flight from Los Angeles to New York, where she was scheduled for a recording session. According to producer Don Hahn, Lansbury arrived at the studio late, after a very long travel day, and refused offers to get some rest and record the song later. She got it right in one take, and one of the greatest Disney movie moments of all time was born.

The Protector (2005)

Though the final product often looks amazing, shooting heavily edited fight scenes can be tedious work, often entailing days and days of close-ups of hands, feet, and faces. Or, you can do what The Protector (released as Tom-Yum-Goong in its native Thailand) did: shoot a badass, four-minute fight scene featuring one hero, one camera, dozens of stuntmen, and lots of stairs, in a single amazing take.

In this sequence, the hero Kham (Tony Jaa) has made his way to Tom Yum Goong Otob, a restaurant specializing in exotic meats where, he believes, a gangster is holding his beloved elephants. Proving just how far one man will go for his animal friends, Kham storms the restaurant's VIP area, where he's confronted by an enormous spiral staircase and a load of henchmen ready to take him out. From here, a Steadicam, Jaa's martial arts skills and fight choreography by Jaa and Panna Rittikrai take over. What's particularly impressive about the sequence is that it's not just a sequence of cool martial arts moves. We get to watch the camera lose track of Jaa, follow the action as a henchman falls or crashes through something, then catch up to him again. The scene is about one hero, but the whole set is used. The result is one of the best fight sequences of the past two decades. Plus, it has arguably the best action hero closing line in the history of cinema.