Movies That Share A Title And Nothing Else

How important is a movie's title? As a 2021 article from Creative Screenwriting (via the International Screenwriters Association) breaks down, a good one can mean the difference between a potential moviegoer buying a ticket, or passing on a movie altogether.

Titles help establish a movie's tone, focus, and mood; they can set expectations of new, unique, compelling entertainment as effectively as any one-sheet or promotional trailer. The wrong title can spell a movie's doom; as Variety posits, would "Casablanca," "Pretty Woman," and "The Breakfast Club" have succeeded if they'd gone to theaters under their original titles ("Everybody Comes to Rick's," "3,000," and "The Lunch Bunch," respectively)?

A great title carries so much freight that from time to time, they repeat. That connection is often the only linking element (legal concerns, typically, scuttle any thoughts of similarly-themed movies from overlapping), leaving moviegoers with a strange, curious entertainment phenomenon. Below, a list of some films which share a title — and absolutely nothing else.

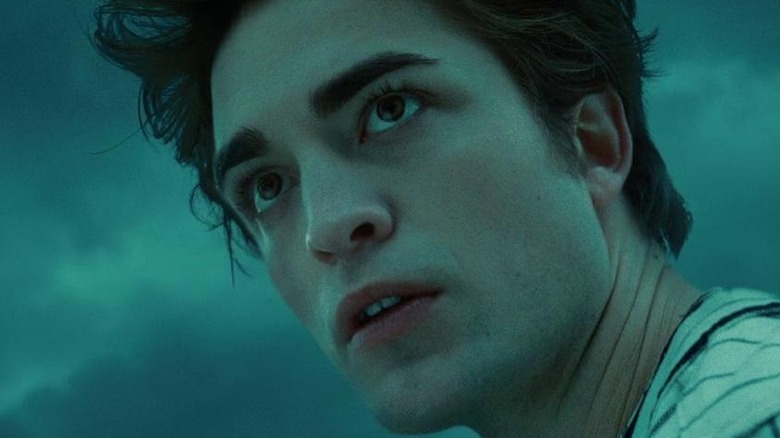

Twilight (2008) and Twilight (1998)

Nearly a decade before director Catherine Hardwicke adapted the Stephenie Meyer YA smash "Twilight," another feature film bore the same name, focusing on a very different relationship than that of human Bella Swan and vampire Edward Cullen. Oscar-winning filmmaker Robert Benton co-wrote and directed the 1998 thriller "Twilight," which featured a cast of Hollywood heavyweights in a noir-fueled story of crime and punishment in and around the film industry.

The cast included no less than four Oscar winners: Paul Newman as an aging private eye, Gene Hackman and Susan Sarandon as former movie stars with a secret, and Reese Witherspoon as their wayward daughter. It also had a host of acclaimed supporting players, including Stockard Channing, James Garner, Giancarlo Esposito, Margo Martindale, and Liev Schreiber, among others. Despite all that firepower and a twist-laden plot, the '98 "Twilight" was a disappointment at the box office, netting just $15 million.

Perhaps because the film was so quickly forgotten, the title easily moved over to the Hardwicke film that would eclipse its box-office take, making some $400 million worldwide. Film detectives may also note that "Twilight" has served as the title for four other films, including international releases from Cambodia, France, and Mexico. But it seems safe to assume nobody else will be titling a film "Twilight" anytime soon, lest they grapple with sparkly vampire jokes.

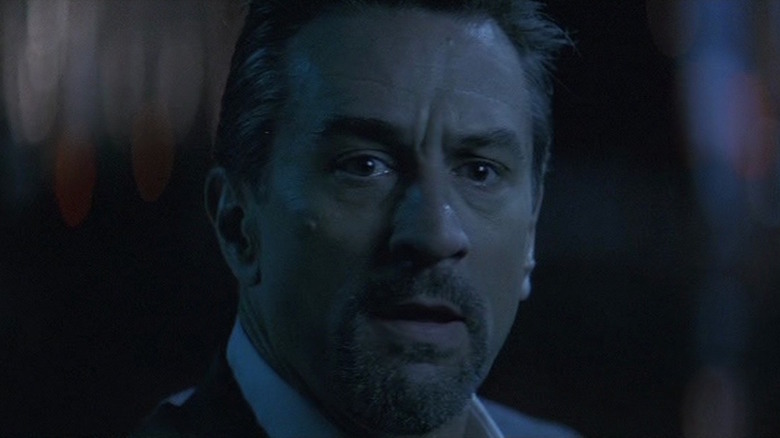

Heat (1995), Heat (1986) and Heat (1972)

Michael Mann's 1995 crime thriller "Heat" earned critical praise for pairing Robert De Niro and Al Pacino as opposite (if equally principled) sides of the law, drawn together over a series of robberies; the film's expertly-crafted action sequences and the acting fireworks of its two legendary leads — on screen together for the first time, albeit for only a few minutes — have made it a favorite among crime film fans and an enduring influence on numerous film and TV productions, as well as several real-life crimes.

If "Heat" remains a well-remembered film, the other pictures that have employed the same title haven't enjoyed the same degree of notoriety. The 1986 thriller "Heat" is best remembered for its numerous production problems, including director Robert Altman abandoning the project and its star, Burt Reynolds, punching out replacement director Dick Richards; a remake, 2015's "Wild Card" with Jason Statham, appears to have been conflict-free but found no favor at the box office.

However, 1972's "Heat" — an Andy Warhol production starring cult actor Joe Dallesandro, actress Sylvia Miles, and tragic Warhol superstar Andrea Feldman as desperate types using and being used by each other – was a critical hit thanks to the name value of its producer and its outrageous on-screen action. Sadly, Feldman died by suicide shortly after the film's completion.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Fast and the Furious (1954) and The Fast and the Furious (2001)

A number of titles were initially considered for "The Fast and the Furious," the 2001 feature that kicked off the phenomenally popular media franchise about street racers, which adds its tenth title, "Fast X," in 2023.

Producer Neal Moritz told Entertainment Weekly in 2016 that the film was billed at various times as "Redline," "Racer X," and "Street Wars," until he saw a documentary about American International Pictures, the company that produced countless low-budget genre films from the 1950s to the 1980s, many directed by the legendary Roger Corman. "They talked about a Roger Corman movie called 'The Fast and the Furious,' and I was like, 'That should be the title of the movie!'"

Though the films share a title and a focus on fast cars, there are actually little to no similarities between the '01 and '54 "Fast and Furious" films. As Corman told Latin Horror in 2021, Moritz paid for the title but not the story (in the EW interview, Moritz noted that Universal also added reels of stock footage to the package), allowing them to keep the street racing angle in the script by Gary Scott Thompson, Erik Bergquist, and David Ayer.

Corman's "Furious" film focused on a truck driver (actor John Ireland, who also co-directed) fleeing a trumped-up murder charge by entering a race from the United States to Mexico in a Jaguar owned by his kidnapping victim (Dorothy Malone). There are two other American films that bear the close-but-no-cigar "Fast and Furious" as their titles — an Ann Sothern comedy-mystery from 1939, and a Reginald Denny silent comedy from 1927 — devoid of both dialogue and the presence of Vin Diesel.

Crash (1996) and Crash (2004)

Mention a movie titled "Crash," and you might face questions about a surprisingly large number of films that share the title.

Most will likely want to engage you in a discussion of the merits of the 2004 Paul Haggis "Crash," which won three Oscars, including best picture, for its examination of racial tension in Los Angeles — today, it is frequently cited as perhaps the worst best picture winner of the century; even fan favorite Brendan Fraser can't escape the vitriol.

Arthouse audiences were surprised to see that film being advertised, however, because barely a decade prior David Cronenberg had employed the title for one of his most controversial films – and for Cronenberg, that's saying something. His 1996 drama starred James Spader and Holly Hunter as symphorophiliacs — individuals sexually aroused by disasters, in this case, car wrecks — and drew criticism and praise in equal measure from audiences, critics, and even other media figures.

Not surprisingly, an eye-catching, simple title like "Crash" has been adopted by a number of other productions over the years: two TV movies, "Crash: The Mystery of Flight 1501" from 1990, and 1978's "Crash," used it for their stories about airplane accidents, while 1977's "Crash!" added an exclamation point for a bizarre horror movie about a comatose young woman (Sue Lyon) who uses the occult powers of an ancient statue to animate various objects — including a Chevy Camaro — to get revenge on her husband. Less well known is the 1974 Norwegian film "Crash," about a young man left disabled after a motorcycle accident, and 1932's "Crash," which concerned a very different sort of disaster: the Wall Street crash of 1929.

The Avengers (2012) and The Avengers (1998)

The two best-known films to use "The Avengers" as their title — the 2012 Marvel Cinematic Universe feature and the 1998 film with Ralph Fiennes, Uma Thurman, and Sean Connery — were both based on venerable properties with enduring followings, but only one delivered a big-screen adventure that satisfied its fanbase.

The MCU "Avengers" was, of course, inspired by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby's comic book, which first united "Earth's Mightiest Heroes" in 1963. The '98 film, meanwhile, drew upon the British cult television series of the same name that paired secret agent John Steed (Patrick Macnee) with a string of formidable and stylish female partners (including Diana Rigg and Honor Blackman) who traded witty banter while foiling foes between 1961 and 1969.

Marvel Studio's "Avengers," which capped Phase One for the MCU, was a worldwide hit, generating more than $1.5 billion in global ticket sales and an Oscar nomination while also setting the stage for some of the studio's biggest hits, including "Avengers: Infinity War" and "Avengers: Endgame." The 1998 "Avengers" was almost its direct opposite; as Peter Bart's "The Gross" noted (via Facebook), it was perceived as a flop even before its release and hastily recut by Warner Bros, which only made its needlessly complicated plot even more confusing. Further complicating matters was a script laden with dreadful puns and an abundance of weird images (Sean Connery in a giant teddy bear costume) meant to evoke the series' cheeky, offbeat humor. The '98 "Avengers" was a huge flop, netting just $23 million in domestic sales against a $60 million budget.

Gladiator (2000) and Gladiator (1992)

Ridley Scott's "Gladiator" may have reaped the acclaim and awards, including best picture and best actor Oscars for star Russell Crowe, but in terms of title, a 1992 boxing drama beat it to the punch. That "Gladiator" starred Cuba Gooding, Jr. and "Twin Peaks" star James Marshall as members of an underground fight organization. Rowdy Harrington, the journeyman director responsible for the Patrick Swayze cult favorite "Roadhouse," oversaw the film, which despite the presence of pros like Jon Seda, Cara Buono, and Brian Dennehy, was a critical and box office flop.

A handful of other movies have used "Gladiator" in their titles, though in these cases, the wording hasn't been exact. Most either used "The Gladiator" — such as the 1986 TV movie by Abel Ferrara about LA motorists stalked by a killer — or the 1969 Swedish dystopian thriller "The Gladiators." That film, by British director Peter Watkins, got the jump on "The Running Man" by envisioning a future in which wars were decided by soldiers battling to the death on a reality-style television show.

Bad Boys (1994) and (Bad Boys (1983)

Mention "Bad Boys" and what comes to mind? Perhaps Inner Circle's theme to the Fox/Paramount Network reality series "Cops?" Or perhaps it's the 1995 action film with Will Smith and Martin Lawrence that used that song as inspiration, having since bloomed into a franchise, with a fourth title announced in 2020. The popularity of that series has largely overwhelmed all the other "Bad Boys" features, including the critically-praised 1983 film that helped Sean Penn break out, playing a troubled teenager sent to a juvenile correctional facility.

You'd be forgiven if you never heard of 1961's "Bad Boys," though the Japanese drama about juvenile delinquents won several awards, including best film from the venerable Japanese film journal Kinema Junpo. The Finnish film "Pahar Pojat" ("Bad Boys") was also a huge hit that ranked second, just below "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King," on the list of top box office winners of 2003. The drama, about a quartet of brothers who turn to crime, doesn't appear to have earned an American theatrical release, but is available on some streaming services.

Child's Play (1988) and Child's Play (1972)

The title "Child's Play," at this point, has been irrevocably claimed by the horror franchise featuring the killer doll Chucky, which as of this writing encompasses seven movies, two shorts, and a series on SyFy/USA Network between 1988 and 2022. But Chucky wasn't the first to employ the common phrase, which refers to something so easy to accomplish that a child could do it.

Director Sidney Lumet ("Dog Day Afternoon") directed a very different "Child's Play" in 1972; that film, based on the Tony-winning play of the same name, concerned a much-hated teacher (James Mason) who believed that a more popular educator (Robert Preston) had turned his students against him.

The '72 "Child's Play" earned mixed reviews from critics like Roger Ebert, who praised the performances and Lumet's direction but ultimately found the film confusing: "The entire movie is set up to suggest supernatural overtones, so when we get a rather conventional Freudian ending, we're disappointed," he wrote in his Chicago Sun-Times review (via RogerEbert.com). Little has been noted about the other films that bear a "Child's Play" title, including a 1954 British science fiction feature, a 1992 German thriller, and a Spanish supernatural horror film from 1995.

Deep Blue Sea (1999) and Deep Blue Sea (1955)

The phrase "between the Devil and the deep blue sea" commonly refers to a problem in which all solutions are bad ones. According to sources, versions of the phrase were first used in the 17th century, and it made its way into the popular lexicon through use as song and book titles.

For science fiction and killer shark movie fans, it also provided the title of 1999's "Deep Blue Sea," a thriller by Renny Harlin that's best remembered for co-star Samuel L. Jackson's outrageous, out-of-left-field death scene and LL Cool J as a scripture-spouting cook with a parrot sidekick. A sizable hit despite its laughable effects, it generated two direct-to-video sequels.

However, a 1955 film has spawned an even greater number of iterations. The British drama "The Deep Blue Sea" was based on a popular stage play by Terence Rattigan about the fallout from a woman's adulterous affair and subsequent suicide attempt. The play has been adapted on numerous occasions: twice for television in 1954 and 1974, twice for radio, and twice as a feature film, the first with "Gone with the Wind" star Vivien Leigh in 1955 and later, with Rachel Weisz and Tom Hiddleston in 2011.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Frozen (2013) and Frozen (2010)

Shocking as it may seem, 2013's "Frozen" marked the first time that Walt Disney Animation Studios — the Walt Disney Company's own animation studio, founded by Walt and Roy Disney in 1923 — won an Oscar for best animated feature. Previous animated feature Oscars went to divisions within the Walt Disney Company, such as Pixar or its live-action entity, Walt Disney Pictures, and while the animation studio reaped countless animated short Oscars, it wouldn't land an animated feature award until the release of "Frozen," which also brought home an Oscar for best original song with "Let It Go."

The global success of "Frozen" — it was the highest-grossing film worldwide in 2013 — and its soundtrack, as well as two shorts and a 2013 sequel, made it almost inescapable, especially for individuals with small children. Its moniker seemed particularly insulting for horror fans, however, who just three years prior had thrilled to "Hatchet" director Adam Green's 2010 horror-thriller about skiers trapped on a lift.

Other movies share the title, including an Indian drama from 2007 and a heady UK psychological drama from 2005, but even if modest critical favorites, they couldn't approach the pop culture juggernaut that the Disney film became.

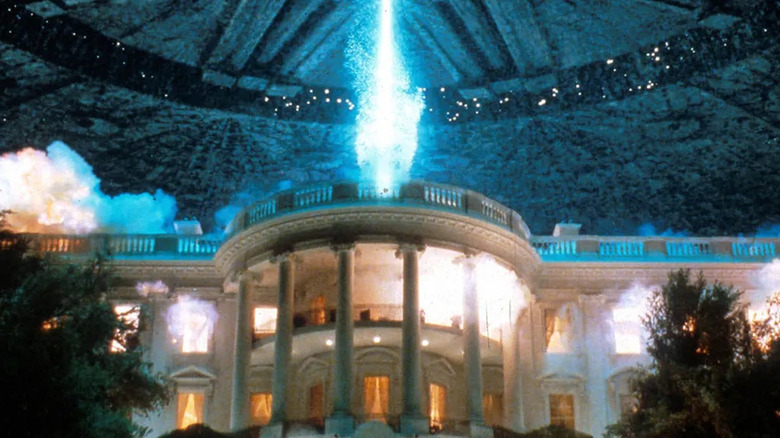

Independence Day (1996) and Independence Day (1983)

Before squandering audience goodwill with an unnecessary sequel in 2017, the title "Independence Day" belonged to Roland Emmerich's 1996 alien invasion film (and yes, the American national holiday). An unabashed crowd-pleaser with Oscar-winning visual effects, "Independence Day" was invariably mentioned any time media observers ticked off a list of Hollywood blockbusters in the late '90s and early 2000s, and it helped to pave the way for such Earth-in-peril pictures as "Armageddon" and "Deep Impact."

By comparison, the 1983 "Independence Day" served as a symbol of the struggle that smaller-scaled, more intimate features often face when trying to reach an audience. Directed by Robert Mandel ("F/X"), the film starred Kathleen Quinlan as an amateur photographer who found it difficult to slip from the bonds of her family and small New Mexico hometown. Despite a talented cast that included an early role for Oscar winner Dianne Wiest, the film was yanked from theaters by its distributor, Warner Bros. Pictures, after it received mixed reviews, and remained almost impossible to see until 2015, when the studio released it on DVD via its manufacture-on-demand imprint, Warner Archives Collection.

Inside Out (2015), Inside Out (1975), Inside Out (1986) and Inside Out (2011)

Let's say someone recommends "Inside Out" for movie night. Great idea, you say — but which "Inside Out" are they referring to? Common consensus would dictate the 2015 Pixar movie with Amy Poehler, Bill Hader, Lewis Black, and Phyllis Smith of "The Office" as the voices of a young girl's basic emotions. It's certainly a good pick — a favorite with critics and audiences alike, as well as an Oscar winner for best animated feature — as well as an endless font of inspiration for memes, and well, an excellent source if you're in need of a good cry.

If there's a budding Tarantino in the room, they might get some arched eyebrows when they say, "Oh, yeah, the 1975 British action film with Telly Savalas and Robert Culp!" while fans of indie movie obscurities might think you're talking about the 1986 film with Elliott Gould as an agoraphobic. There's even a chance that the wrestling fan in your life could be convinced that you mean the 2011 "Inside Out," which features the dizzyingly surreal combination of Paul "Triple H" Levesque, Parker Posey, and Michael Rapaport as leads. But let's be honest, most people mean the Pixar movie.

Rush (2013) and Rush (1991)

There are two very good films called "Rush," and while they have absolutely nothing to do with one another, they're both worth your time. The 2013 "Rush" may be the one audiences are most familiar with, as its the more recent of the two. That drama, directed by Ron Howard, chronicled the rivalry between Formula One drivers James Hunt (played by Chris Hemsworth) and Niki Lauda (Daniel Bruhl of "The Falcon and the Winter Soldier"). A thrilling picture and an involving drama about the price of obsession, "Rush" was critically acclaimed — as was 1991's equally excellent "Rush."

The directorial debut of producer Lili Fini Zanuck, "Rush" starred Jennifer Jason Leigh and Jason Patric as narcotics cops whose use of narcotics during undercover operations cost them their jobs. Authentically gritty and fueled by excellent performances, including a menacing turn by rocker Gregg Allman as a crime boss, "Rush" is perhaps best remembered today for its Eric Clapton score, which included the Grammy-winning single "Tears in Heaven."

Venom (2018), Venom (1966), Venom (1971) and Venom (1981)

Marvel Comics introduced an early version of the alien symbiote Venom as a sentient replacement suit for Spider-Man in "Marvel Superhero Secret Wars" #252 in 1984 and gradually developed the ravenous entity across several "Spider-Man" titles until its full-fledged debut in the host body of reporter Eddie Brock in "Amazing Spider-Man" #300 in 1988. Since then, Venom's popularity with readers led to appearances in many of Marvel's animated series, as well as a much-derided live-action debut in "Spider-Man 3" before earning its own marquee title via Sony's Spider-Verse with 2018's "Venom" and 2021's "Venom: Let There Be Carnage," as well as a mid-credits appearance in "Spider-Man: No Way Home."

But before Marvel unleashed Venom, the name applied to several horror- and suspense-themed features between 1966 and 1981. A Danish adults-only feature called "Gift" (the Danish word for "poison") from Denmark adopted "Venom" as its American release title in 1966, and a deeply weird 1971 British horror about a woman with a poisonous touch employed it as one of several alternate titles, including "The Legend of Spider Forest." Cult fans also know "Venom" as the title of a 1981 British feature about a kidnapping plot foiled by a rogue black mamba; the film was noted for director Tobe Hooper ("The Texas Chain Saw Massacre") jumping ship mid-production, and according to director Piers Haggard, for off-camera combat between its controversial stars, Oliver Reed and Klaus Kinski.

It (1990, 2017), It (1958) and It (1967)

For modern audiences, "It," as a title, largely belongs to Stephen King's epic 1986 novel and its two screen adaptations — the 1990 TV miniseries and the two feature films released in 2017 and 2019. But "It" has also served as the title for a wide array of other film and video projects; followers of the jam band Phish know "It" as the title of a two-day festival (and accompanying DVD) featuring the group from 2003, while classic sci-fi devotees recall 1958's "It! The Terror from Beyond Space," often cited as one of the inspirations for "Alien."

There's also 1967's "It!" a British horror film with Roddy McDowall as a museum employee who discovers a golem — a statue that comes to life in Jewish folklore — and uses it for his deranged purposes, and a 1989 Russian satire about the development of a town filled with corrupt and inept leaders. However, classic film devotees know "It" as the title of a 1927 breezy silent comedy with screen legend Clara Bow as a brassy shopgirl who sets her sights on landing her wealthy boss. The film's popularity helped introduce the idea of the "it girl," one still in use nearly 100 years later, referring to a young woman whose popularity was due to an indefinable but undeniable combination of charisma, social standing, and sex appeal.