Warrior Nun's Demise Carves Out The Perfect Opening For Hollywood To Finally Get Joan Of Arc Right

Content warning: the following article contains mentions of sexual assault.

A lot of time has passed since Netflix's unceremonious cancellation of "Warrior Nun." Despite the determined efforts of its zealous fandom, it doesn't appear that Netflix, a company that's been happy to pick up other networks' droppings regardless of their smaller followings (see: "Lucifer" and its 3.5 million renewal tweets vs. the 10 million championed by #SaveWarriorNun), has any interest in reviving this female-led, LGBTQ+-friendly, YA comic book adaptation.

Thus, in the absence of a "Warrior Nun" resurrection, maybe it's time to turn our attention to another young female warrior — one whose story Hollywood has yet to tell in a way that gives her the credit and respect she deserves. To her family, she was simply Jehanne. To her soldiers, she was La Pucelle, the Maid of Lorraine, and of Orléans. To her followers, she was a savior. To her enemies — including the very same church that would later deem her a saint — she was a heretic, an idolater, and a witch.

History, though, would know her as Joan of Arc.

And although the world of cinema has given us some compelling depictions of her trial and martyrdom, more recent attempts to explore her life and "hero's journey" have been less successful. Partially because Joan is both the hero and the hero's "supernatural aid," and partially because our modern worldview prohibits us from accepting the supernatural as historical, many depictions have been plagued by anachronistic (and ultimately reductive) interpretations and themes. However, the influence of "Warrior Nun" has opened a doorway to finally telling a proper Joan of Arc story, which could deal with similar themes, understand the historical context, resist the urge to substitute symbolism for reality, and tell a tale with great relevance to contemporary audiences.

Joan of Arc, 101

Let's start with the story most folks "know," about the young, illiterate shepherdess and would-be saint.

In 1425, in the rural French village of Domrémy, 13-year-old Jehanne began hearing voices. At first, they instructed her simply to be pious. But with a divided France at war with England, the disinherited French heir to the throne (aka, the Dauphin) holed up with his supporters (the Armagnacs) in Chinon, and the English and their allies (the Burgundians) gaining territory, there was work to be done. Joan's voices told her to obtain an army, lift the siege at Orléans, and lead the Dauphin to Reims to be crowned. On God's orders, she was to unite the French, and drive the English out.

Around the age of 16, she set out to do just that. In May of 1428, Joan convinced her mother's cousin to take her to Vaucouleurs. Somehow, Joan persuaded its captain (Robert de Baudricourt), to give her a horse and some men, so that she might travel — through enemy territory — to Chinon Castle. For the trip and task ahead, she cut her hair and dressed as a boy. At Chinon, Joan won over the Dauphin by correctly identifying him in the crowd, and sharing a "sign" that only God (and he) would know. That May, her army lifted the months-long Siege of Orléans, and on July 17th, 1429, the Dauphin was crowned in Reims.

Then the wheels came off. Joan was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, imprisoned, "tried," and found guilty of heresy by a pro-English ecclesiastical court. In 1431, Joan was burned at the stake. The Dauphin did nothing. 25 years later, a rehabilitation trial would exonerate her posthumously. 460 years later, the Catholic Church dubbed her a saint.

Context is king, when it comes to adapting Joan of Arc's tale

The problem with this "checklist of events" version of the story is that it robs the narrative of crucial context, and Joan of the admiration she deserves. Using the lessons that "Warrior Nun" has taught us about understanding religious and historical context, a new Joan of Arc series could get this right. And to tell Joan's story in a way that makes sense — and that, subsequently, reveals her actual triumphs — we have to go back, to a decade before her voices began, and a muddy field approximately forty miles northeast of Domrémy.

Joan was just three years-old when England's King Henry V dealt a devastating blow to the French at the battle of Agincourt. In an effort to cement his right to the English throne, Henry V reignited the Hundred Years War, and stormed into France to reinstate an ancient English claim to the French crown. The timing was ideal. France was a collection of rival fiefdoms all vying for power under the ineffective and easily-manipulated rule of a king so mad he was convinced he was made of glass. As the French King Charles VI slipped further into his own delusions, the nobles of France went to war with themselves, and England took full advantage. Henry V's lowborn English archers cut down the flower of the French nobility within hours. In the end, between over 6,000 of France's elite lay dead.

Out of the chaos, two factions arose: the Armagnacs, who supported the Dauphin (the mad king's son), and the Burgundians, who supported the Duke of Burgundy. When one Duke of Burgundy, John the Fearless, was assassinated in 1419 by the Dauphin's supporters, his son and heir made an alliance with the English.

Yolande must play a key role in a Warrior Nun-inspired Joan of Arc series

To understand Joan of Arc, we need to understand the importance of religion in that era. Modern depictions generally try to "explain" Joan's voices as an outlier — ignoring that in the 15th century, voices, visions, and prophecies were everywhere. People believed God had a tangible hand in everyday affairs and that everything that befell them, be it bad or good, was a result of their own piety or sinfulness. To people at the time, there wasn't a question of "belief" or "delusions," but to them, an accepted reality — one that extended into politics and warfare.

Agincourt had convinced Henry V that God was on his side. It would take an equally "miraculous" event to convince the apprehensive and indecisive Dauphin that god was on his side. Without that conviction, his France would undoubtedly be lost forever. One woman understood this better than most, but her name was not Joan, and she was no peasant.

Yolande of Aragon — the Dauphin's mother-in-law and the queen of Sicily by marriage, but also regent to parts of France — had long influenced politics. For years, she'd facilitated diplomacy and stability amidst in-fighting, greed, and generational grudges. Her daughter, Marie of Anjou, was married to the Dauphin, and Yolande was a surrogate mother and political mentor for the prince. Despite the Dauphin's intelligence, his paranoia made him easy to manipulate, and slow to act: thus, Yolande stepped in, and a successful Joan of Arc series needs to recognize her role as a prime mover of the narrative.

Yolande plays a pivotal part in Joan of Arc's ascension

In "The Maid and the Queen," Nancy Goldstone uses long (long) overlooked evidence to argue that it was Yolande who set the stage for Joan's rise to prominence. "An unusual prophecy, attributed to a seer from Provence named Marie of Avignon, began circulating throughout southern France," she writes. "The first of these was that 'France, ruined by a woman, would be restored by a virgin from the marches [border region] of Lorraine.' The second was that 'a Maid [a virgin] would come... who would carry arms and would free the kingdom of France'" (p. 92).

The "viral" prophecy likely came straight from Yolande, with intention. She had grown up in a court of poetry and romance, and she knew all too well the power that such stories had. She herself was fascinated by "The Romance of Mélusine," a work whose parallels to the Maid's story and the conflict in France are impossible to miss. In all of French history prior to the 15th century, it's the only work involving a female savior. And, as the "Harry Potter" of its day, it was a story well-known to just about everyone, as was the prophecy it inspired.

Crucially, Joan was not the only young peasant girl who spoke to God — which makes what she did all the more incredible. Imagine (as Hollywood has so often failed to) the strength, intelligence, and impenetrable belief and determination it must have taken for this one lowly peasant girl — no different, in terms of her standing, lack of education, and upbringing, from any other pious, lowly peasant girl — to succeed not only in positioning herself as the prophesied savior of France, but to go on to, well, actually save France.

Classic Hollywood didn't understand Joan of Arc

When productions fail to paint a picture of the exact France into which Joan was born, and when they ignore how the 15th century world operated, they make it almost impossible to understand some of Joan's actions, much less find any inspiration or meaning in them.

For instance: why oh why, a viewer might ask, would Joan continue to support Charles VII — and continue to believe in and fight for him, right up until her death — even after it became clear that he was done with her mission, had more interest in treaties and truces than warfare, and had no intention of saving her? Too often, when directors attempt to address this question, they fail to acknowledge Joan's literal belief in her voices. Unfortunately, this almost always has the effect of painting her as naive, delusional, weak, or just plain dim.

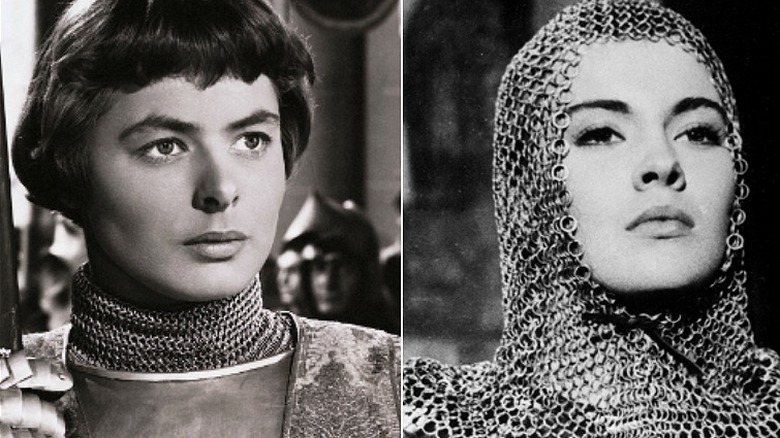

In "The Wizard of Oz" director Victor Fleming's "Joan of Arc" (1948) — in which a 33-year-old Ingrid Bergman attempts to portray a teenage girl, a fact that only further hurts Joan's credibility — it's not even Joan's own idea to stand by her cause. One of her brothers at arms "explains" to her that if she speaks against Charles VII, it will only make things worse. In Otto Preminger's "Saint Joan" (1957) — a film that turns George Bernard Shaw's brilliant play into an inane version of "A Christmas Carol" — Jean Seberg's Joan doesn't come out much better, and is essentially too proud, too young, and too stupid to acknowledge the reality before her. And yet, neither of these films are as disappointing as 1999's "The Messenger: The Story of Joan of Arc," starring an unfairly-directed Milla Jovovich.

The Messenger was the weakest Joan of Arc attempt to date

"The Messenger" starts out on the wrong foot, and gets worse as it goes. While it's one of the few films that gives us Yolande (Faye Dunaway), she's relegated to a archetypal background "she-wolf," and the movie's sins only get worse from there.

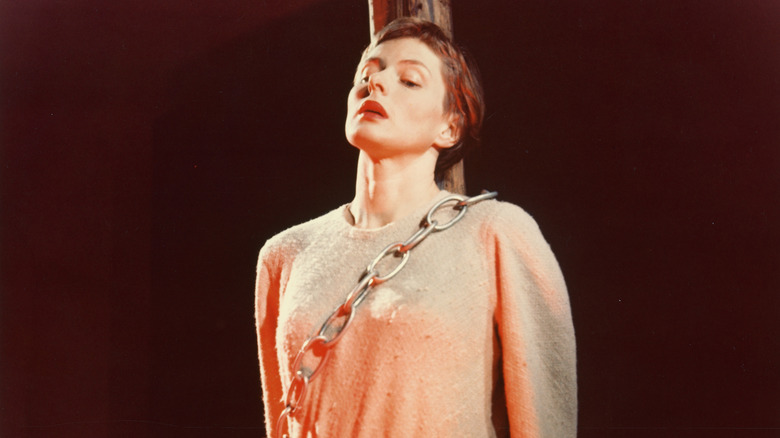

Here, little girl Joan witnesses the (egregiously gory) sexual assault and murder of her sister Catherine, fulfilling the exhausted stereotype of all medieval fiction and fantasy that strong female characters are seemingly required to have their entire personalities, motivations, and trajectories formed by such acts. Though the film makes a passing, clumsy attempt to explore Joan's trauma, it's far too heavy a topic for the uneven writing to navigate. Instead, we're left with the classic Hollywood madwoman. Jovovich delivers every line screaming or whimpering, bug-eyed or bleary-eyed, breathless or ranting. When she's imprisoned, she has a Hollywoodized schizophrenic break. Dustin Hoffman appears as her conscience, and gets her to admit that her mission had nothing to do with God.

It all boils down to yet another depiction of a woman who has no actual agency, and is — from start to finish — a victim. In an attempt, perhaps, to counteract this, we're given a healthy dose of the most cartoonish, lazy feminism ever to find its way into the 15th century: "To you, I'm just a 'girl!'" Joan pout-yells in disbelief at her captain, before dramatically chopping off her hair at the siege of Orléans. Sadly, the film's attempt to superimpose modern understandings onto a 15th century narrative results in a borderline offensive investigation of trauma. Thankfully, 1999's other Joan production (it was a real banner year for the Maid) gets us slightly closer to where we need to be.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Sobieski did Joan of Arc justice, but could have used a full series

There may be no greater evidence for the fact that Joan's story deserves and requires a full-length series than 1999's "Joan of Arc," a roughly three hour-long miniseries starring Leelee Sobieski. Not only does it provide a relatively thorough historical introduction, it also gives us an age-appropriate lead, a realistically complex Dauphin/Charles VII (Neil Patrick Harris), and a somewhat historically accurate order of events. It allows us to linger on Joan's often rushed-passed path to the Dauphin, meaning we're able to see just how much of an anomaly it was that she ever found her way to Chinon to begin with. Then, of course, there's Sobieski.

Joan's real life rehabilitation trial saw 115 witnesses speak to her purity, piety, and goodness, often with such enthusiasm and obvious hyperbole that when directors rely on that testimony for their portrayal of her, the result is a woman made one-dimensional in her perfection. Luckily, Sobieski manages to imbue her Joan with equal parts vulnerability, plausibility, and strength. What's more, while technically aimed at a slightly younger audience, "Joan of Arc" doesn't hold back on the chaos and desperation of unending war — a backdrop that's absolutely crucial to understanding Joan's fervor.

Unfortunately, because it's aimed at a slightly younger audience, and very much a product of its time, the miniseries occasionally can't help itself. In addition to giving Joan an unnecessary "plutoni-crush," the mini-series maintains an anachronistic thread of "girl power" for much of its first part. Moreover, Yolande is left out entirely (though the prophecy is not) and Peter O'Toole's Pierre Cauchon — essentially, Joan's own Pontius Pilate — ends up being inserted in inaccurate parts of the story.

A Joan of Arc series needs to understand her as a real person

The films that have succeeded in giving us a meaningful and dignified portrayal of Joan — e.g., Carl Theodor Dreyer's renowned "La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc" (1928) and Robert Bresson's "Procès de Jeanne d'Arc" (1962) — have focused solely on her trial at Rouen (they're also, unsurprisingly, French).

Joan's trial is a tempting chapter to zero in on. After all, as Mark Twain wrote in his own Joan narrative, "The details of the life of Joan of Arc form a biography which is unique among the world's biographies in one respect: It is the only story of a human life which comes to us under oath." In the transcripts of the Great Trial of 1431 and the testimony of her supporters years later, we see the inhumanity, perversion, and cruelty of her captors and prosecutors. And in her articulate, disarming, and unwavering responses to their ceaseless interrogation, we see not only her astonishing strength and unbreakable spirit, but her wit, intelligence, compassion, and vulnerability as well. When asked (in an attempt to trick her into presuming to speak for God) if she believed she was in god's grace, this weakened, abused, malnourished, illiterate and uneducated young peasant famously answered: "If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me."

And therein lay the problem for the church: Joan refused to accept their authority on the matter. It was God, and God alone, who could render such a judgement, even on earth.

There's only one way to conclude a Joan of Arc series, but the little details matter

Since Joan was (once again) subjected to an invasive physical examination that proved her virginity, she couldn't be found guilty of witchcraft. Witches, after all (and as everyone knows) seal their pact with the devil via intercourse. She would have to be found guilty of heresy and idolatry instead, and by whatever means necessary. Joan was kept in shackles throughout her imprisonment, frequently threatened with torture, and watched over by male English guards who mocked and tormented her. For her own safety and modesty, she continued to don the clothes of a man, a point of such contention for the church that the debate over whether or not her attire was heretical would ultimately prompt both her execution and her rehabilitation trial.

Finally, Joan reached a state of such deterioration that Cauchon coaxed her into signing a confession renouncing her voices. As a confessed heretic, she should, by law, have been imprisoned by the church. She was ordered to put on a dress, which she did, but she was not sent to a new location. Instead, she was ordered back to her cell, and back to her English guards. Days later, Cauchon found she had once again donned her male clothing. Though it was clear she did so for her own safety (and that she may even have been forced to, since no one knows how she obtained the garments) this move sealed her fate: she was now a relapsed heretic, and the secular court would put to death.

Joan recanted her coerced confession, and she was burned alive on May 30th, 1431. Her heart, which remained intact, was twice cremated before being thrown into the river Seine.

Joan of Arc has a massive, complex legacy

What Joan accomplished in the course of her short but remarkable life is so incredible that it's often hard to believe. But what she accomplished over the course of her trial — and the determination and dignity with which she faced her death — are so incredible that it's proven impossible to forget.

In the centuries since her murder, Joan has been used to represent everything from Protestantism to the Divine Right of Kings, and from Marxism, Feminism, Nationalism, and Civil Rights to, in more recent years, conspiracy theorists and far right politics. But when the context and specific circumstances surrounding her narrative are ignored, or tweaked to fit a given era's attitudes or debates, it's not just Joan who suffers. To tell her story, but only part of it, or only the elements we can reduce to tidy symbolism and metaphor, is to rob ourselves of the important lessons we might still glean from her journey, and from the girl herself.

As Helen Castor notes in "Joan of Arc: God's Warrior," "If [Joan] becomes all things to all people, we risk losing the human being. The girl who burned in this place was a ferocious champion of one side in a bloody civil war. She was able to do what she did, to achieve what should have been impossible for someone of her class and sex, because she and all those around her believed they were fighting a war in which god's will was at work. And perhaps it's there, in the possibilities that faith can create, and in the violence it can bring, that Joan's worlds and ours don't seem so very far apart."

Which circles us back to Netflix's unfairly canceled "Warrior Nun."

Joan of Arc's rehabilitation, take 2

Simon Barry's beloved adaptation never got the change to fully explore its most ambitious themes, including the many ways in which faith — be it in a deity or wealth, ourselves, or something as seemingly benign as celebrity — operates, drives, advances, impedes, creates, and destroys a society. Joan's story may not speak with such clear-cut directness to how these things manifest in the 21st century, but it's every bit as relatable and relevant. And "Warrior Nun" equips creative talent with a lot of tools to make a new "Joan of Arc" work.

Are there not still those who harbor a (literally) medieval obsession with the anatomy and attire of others? Are there not still powerful institutions, and individuals hungry for power, who will exploit the obsessions and superstitions of the public for their own gain? Are there not still those in a position of authority who'll break the law in the name of "God," or in order to "maintain order?" On the other hand, and far more importantly: are there not still those without any power — without, in fact, any access to it — who'll risk their freedom and their lives to stand by what they know to be true?

If a series were willing to tell Joan's story — in its entirety, and without sacrificing the reality of the girl and the world in which she lived for easy, anachronistic commentary — we might finally be able to offer her a genuine rehabilitation. Joan already has plenty to say about the world in which we live. It's just that, despite Hollywood's inability to see this, it's a lesson she can only share through her 15th century lens.

That lesson is, quite bluntly, that in the 592 years since her death, humanity really hasn't changed that much.