Freddy Krueger Is Dead - But New Nightmare Holds The Key To A 21st Century Revival

Despite the insistence of some die-hard fans that the "Nightmare on Elm Street" franchise is dead, talk of an upcoming reboot continues to swirl. It's been four years since Bloody Disgusting announced that Wes Craven's estate was taking pitches, but the recent success of a pile of '80s and '90s horror reboots — including returns to Wes Craven's own "Scream," John Carpenter's "Halloween," Clive Barker's "Hellraiser," and now, a potential resurrection of Friday the 13th — certainly points toward Freddy's return being ineveitable.

If we must return to Elm Street, then, inspiration should only be drawn from the one Freddy film that's not only capable of making the leap to the 21st century, but that — in its original, 1994 form — had plenty to say about the world in which we now live.

"Wes Craven's New Nightmare" is often talked about as his first foray into the world of meta on his journey toward "Scream." In truth, "New Nightmare," unlike "Scream," is actually meta, whereas the latter is more of a commentary on its genre. In "New Nightmare," actors appear as themselves, Craven appears as himself, the themes and thesis engage the (then dead) Freddy franchise itself, and the fourth wall doesn't exist — or at least, isn't depicted as existing — at all. And it speaks, with unsettling prescience, not simply to the horror genre, but to the very nature of storytelling, and the relationship between creator and creation.

In 1994, the film was a surprisingly insightful installment, given the slap-dash nature of the sequels that preceded it. In 2023, a similar exploration would speak, as only horror can, to today's existential threats. More than that, as a film that asks us to care about who owns a narrative, "Wes Craven's New Nightmare" embodies, in so many ways, our current reality.

Wes Craven's New Nightmare is a prophetic nightmare

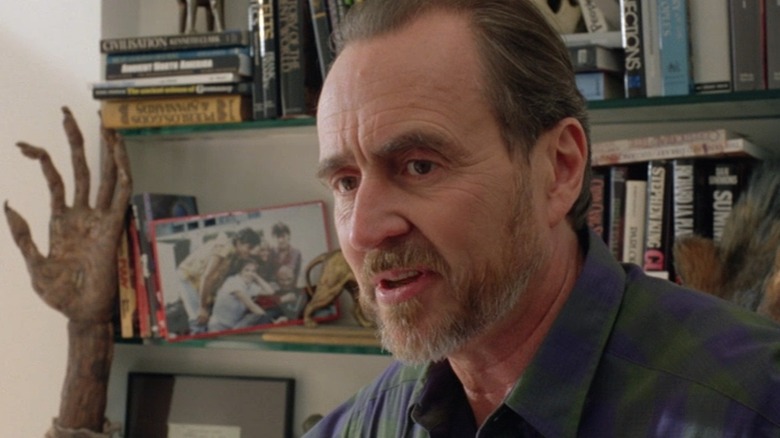

In "New Nightmare," final girl Heather Langenkamp (playing herself, not Nancy) is having violent dreams about her fictional foe, Freddy Krueger. Her husband dies in a car crash after falling asleep at the wheel, and her young son Dylan (Miko Hughes) slips into trance-like states, in which he appears to be channeling the monster himself. Meanwhile, Heather is asked to star in another sequel, and as her son slips away, she seeks helps from Robert Englund (who played Freddy in the films), her friend John (Saxon, her policeman father in "Nightmare on Elm Street") and, ultimately, Craven himself.

When she confronts Craven about the new movie, he confesses that while he's not totally in control of the script, he knows why this is: an ancient, evil entity that's taken different forms over the centuries has now taken over the form of Freddy, and it is attempting to break out into the real world. When Heather asks if it has any weaknesses, Craven explains it can be captured only by storytellers. As Craven tells it, "Every so often, [storytellers] imagine a story good enough to sort of catch its essence... and then for a while it's held prisoner in the story [...] but the problem comes when the story dies [...] It can get too familiar to people ... or somebody waters it down to make it an easier sell. You know, or maybe it's just so upsetting to society that it's banned outright. However it happens, when the story dies, the evil is set free."

When he says that only Heather can stop it, she's confused — she's Heather, not Nancy. However, as Craven puts it, "It was you that gave Nancy her strength."

One, two, Freddy 's feeding on you

"New Nightmare" came out in 1994. Almost 30 years later, though, Craven's discussion with Heather embodies why it's the perfect model for revisiting the "Nightmare on Elm Street" franchise — because it was not only ahead of its time, but spoke to contemporary debates we couldn't have predicted back then.

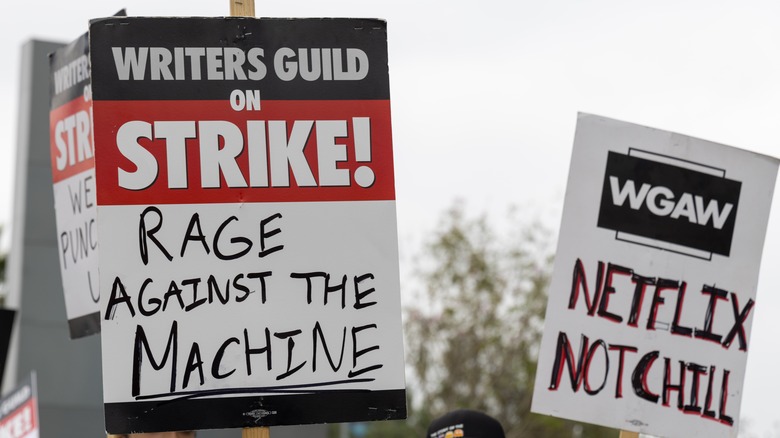

First, there's creativity as it relates to key concerns (read: AI tech) in the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike. Next, there's the terrifying trend of parents and politicians trying to restrict history teachings as well as (already marginalized) narratives in schools. Finally, there's the increasing lack of control we have over the stories we read, believe, and share in the age of misinformation.

If you've ever had an infuriating argument about basic facts, or struggled to determine the accuracy of a story, you know that the single most polarizing debate in our society today circles around how all of us exist in slightly different realities, reading slightly different truths tailored to maintain our attention or blindly reinforce our beliefs. The feeds we feed off of can contain factual information, but truth and accuracy are not their goal. Their goal, as "The Social Dilemma" made abundantly clear (and as the existence of QAnon has proven) is our attention, our engagement, our clicks, and our data. Ultimately, it isn't a truth-focused, human storyteller who controls the narrative we tell ourselves about ourselves and the world in which we live, but an algorithm — one that, just as Freddy does to Heather (and Nancy), uses our own vulnerabilities against us.

Freddy will always have the upper hand because human beings need to sleep. And now that we've created the internet (just as the townsfolk inadvertently created Freddy), it will always have the upper hand.

Freddy Krueger is the monstrous embodiment of the algorithm

In "Why We're Polarized," Ezra Klein notes that while research can lead us to accurate answers, it often digs us deeper into misinformation, as we strive to validate our preexisting knowledge. That's right, folks: at the risk of really ruining your day and your perception of yourself (and of your opposition), it turns out that human beings are far, far more concerned with proving we're already right about something than with uncovering whatever the "true story" is. Profit-driven algorithms not only run on, but learn from and rely on this frailty — just as Freddy relies on our need for sleep, and as our inability to control our dreams allows him to control us within them.

The scariest thing about Freddy has always been that the call isn't just coming "from inside the house," but from inside our very own mind. Similarly, we create — but do not control — the narrative(s) our digital world propagates and reinforces for us. And it's not just the hundreds of millions of people all over the world who get their news from social media who are prone to such a loss of narrative control. That oh-so newsworthy campaign story you read in your super legit and truth-motivated (likely online) newspaper? Yeah — that came from social media (read: an algorithm), too.

As Craven says in the film, "The genie's out of the bottle, Heather [...] he's sort of gotten used to being Freddy now... and he likes our time and space, so he's decided to cross over."

New Nightmare reshapes the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise as an allegory for contemporary issues

While a number of potential "Nightmare on Elm Street" reboot concepts would likely want to tackle dreams as a metaphor for digital illusions, there's something special about the meta focus "New Nightmare" takes on how a story dies, which also truly feels as if it was written for 2020s America.

When Heather brings Dylan to the hospital after one of his trances, she's peppered with questions about whether or not she exposed him to her movies. "Those films can tip an unstable child over the edge," she's told. While she didn't intentionally show him one, she knows he's seen scenes from it. What she doesn't realize until after she and Dylan defeat Freddy is that proper exposure to a story — particularly a story that scares us, or makes us uncomfortable — is what helps keep its horror contained. In the end, it's Dylan's familiarity with a very dark folk tale (Hansel and Gretel) that allows him and his mother to triumph over Freddy.

It's hardly a new idea, and yet it's one many seem to have forgotten in their rush to ban books, hide and deny history, and stifle learning in the guise of "protecting" children. Logic, and not an algorithm, suggests that if we fear the things we don't know, and we hate the things we fear, then the way to prevent fear and hate is to (crazy as it might sound) learn about the things we don't know, or haven't yet learned about. And when it comes to containing an evil by telling its story, isn't there a saying, or something, about being doomed to repeat the history — and, in so many cases, the real-life horror — that we don't know?

New Nightmare's focus on storytelling should inform a new reboot

If you're at all familiar with the current WGA and SAG-AFTRA strike, you know that protections against AI technologies like ChatGPT are a major sticking point for writers. The WGA asked studios to "regulate use of artificial intelligence on MBA-covered projects: AI can't write or rewrite literary material; can't be used as source material; and MBA-covered material can't be used to train AI." The AMPTP rejected the proposal, instead offering annual meetings to discuss AI, according to CBS News.

It's tempting to think that AI won't replace writers and actors, as evidenced by that bot-penned Olive Garden commercial, and the fact that, when put to the test, all this technology has ever managed to produce are crappier versions of movies that already exist. But technologies like this advance rapidly, and exponentially, and studios and streamers are already using AI technology to determine what movies get made, per The Verge, and what series end up in our "for you" feeds. What's more, studios are very much okay with "crappier versions of movies that already exist," so long as they turn a profit (see: the 101 live-action Disney remakes).

The acceptance of money-printing mediocrity is nothing new, and it's noteworthy how Craven's Craven character lists this explicitly as a reason that a story dies — that is, either it becomes too familiar, or is watered down into an easier sell.

Freddy Krueger, as an iconic (and oft-recycled) IP, could represent the dangers of recycling iconic IPs

Even if you are content to live forever in the land of reboots, remakes, requels, and preboots, the truth is that such an approach will eventually halt pop culture in its tracks ... or, perhaps, mean that it just keeps spinning in circles, meaninglessly, forever. And that stagnation in our storytelling culture — a culture that's defined us as humans for millennia — has serious consequences for our species.

In 2014's "The Psychological Comforts of Storytelling," Cody C. Delistraty writes, "Stories can be a way for humans to feel that we have control over the world. They allow people to see patterns where there is chaos, meaning where there is randomness. Humans are inclined to see narratives [because] it can afford meaning to our lives — a form of existential problem-solving."

But as "Wes Craven's New Nightmare" asks: what happens when we lose control of the very thing that gives us some semblance of it? The film's answer to this, in 1994, was simple: evil wins. The entity breaks through and takes over, and the only two people who might be able to stop it are (1) a writer and (2) an actor. Two very real, very human storytellers.

That Craven could not have known he was speaking decades into the future doesn't negate the film's foresight. And as the line between the digital world and the real world grows increasingly imperceptible — and as technology grows increasingly adept at "creating" (read: regurgitating) and controlling our stories — Craven's question takes on a whole new urgency. Thus, while a 21st century reboot might, indeed, be little more than a retread of what we previously watched in 1994, it could also lend some necessary, meta perspective to a world that's forgotten something deeply important.

Freddy Kreuger's new nightmare is the nightmare of our times

What happens when stories themselves — when the biological imperative that helps us process randomness and chaos as a means of "existential problem-solving" — are not only beyond our control, but the product of randomness and chaos? Not, of course, in the most literal sense — since algorithms are nothing but pattern, calculated variation, and predictability. They are, however, random in the sense that they have no understanding of the experiences, emotions, moralities, and conflicts they attempt to replicate, and to which they (appear to) speak. They can't tell the truth from a lie, and they can't (for now, and the foreseeable future) tell us anything we don't already know — or, more disturbingly, that we don't already think we know.

What becomes, then, of the problems humanity has yet to solve? A world taught by machines that can learn "new" things from us, but from which we can learn nothing new, is a world doomed to repeat past failures with even greater uniformity and accuracy than it already does. In that world, Freddy wins — because he has to. He wins because if he doesn't, he can't come back for another repetitive, predictable sequel. His defeats are only temporary because they're the result of temporary solutions (solutions that have already been tried, and that have failed again, and again), and his victory is greater because it isn't merely the "murder of innocence," but the murder of imagination — that is, the complete and total death of our ability to fathom what has never been fathomed before.

And if we lose that, we lose the very thing that, for all these centuries, has kept our self-destructive species alive: our ability not simply to create, but to interpret, deeply feel, and learn from the stories we tell.