How The Joker Became So Sick And Twisted

In the entirety of the superhero genre — and arguably the entirety of fiction in general — there's no character who embodies terrifying, homicidal insanity more than the Joker. He's the DC Universe's most prolific killer in a walk, an "agent of chaos" whose unpredictable actions mask meticulously constructed schemes, an amoral sadist who has dedicated his criminal career to tearing down the very ideas of order and stability. He's been a part of some of the most controversial stories in comics, and despite the overwhelming popularity that has led to countless appearances, he's managed to maintain an edge that makes him feel truly dangerous.

But that wasn't always the case. Just like Batman himself, the Joker didn't arrive fully formed, and while a few of the basics might've been there from the beginning, he's undergone a whole lot of changes, revisions, and reversions over the past 80 years. Here's how we got from a one-shot gimmick villain to the embodiment of madness and mayhem — and how he was almost completely forgotten along the way.

The Man Who Laughs

It might be hard to believe now that he's the cornerstone of a genre in a medium that he helped to define, but when he first hit the pages in 1939, Batman wasn't exactly an original concept. Bill Finger and Bob Kane were heavily influenced by the Shadow, a pulp vigilante who eventually found himself replaced in the pop culture pantheon by Batman. In fact, the story that introduced Batman, "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate," was, to put it charitably, "inspired by" (read: lifted its entire plot from) a Shadow novel called Partners of Peril that had been released a few years earlier.

Before long, of course, Batman emerged as his own character. Six months after his debut, he got the origin story that remains unchanged to this day, and five months after that, Finger and Jerry Robinson introduced Robin, who redefined the idea of a sidekick and inspired a thousand knockoffs himself. Still, those stories were never exactly subtle about where they were digging up their ideas. Finger was even known to carry around a "Gimmick Book," in which he'd write down anything that he thought would make a good story. That's how the sight of an advertisement for Kool Cigarettes led him to create a bad guy called the Penguin.

Enter German actor Conrad Veidt. In 1928, he'd starred in a silent film called The Man Who Laughs, about a 17th-Century noble named Gwynplaine. His father had been killed in an iron maiden by political rivals, and as for Gwynplaine himself, they "carved a grin upon his face so that he might laugh forever at his fool of a father." Gwynplaine grows up, gets revenge, and actually gets a much happier ending than he gets in the Victor Hugo novel on which the film was based.

The important part for the then-new Batman comics, however, was the striking image of a man whose face was permanently twisted into a grin, forced to smile no matter what emotion he was actually feeling — something that Veidt did very well in the film. Finger was inspired by that incredible visual, and brought the idea to Jerry Robinson just in time for Batman to get his second monthly comic, appropriately titled Batman.

Enter: The Joker

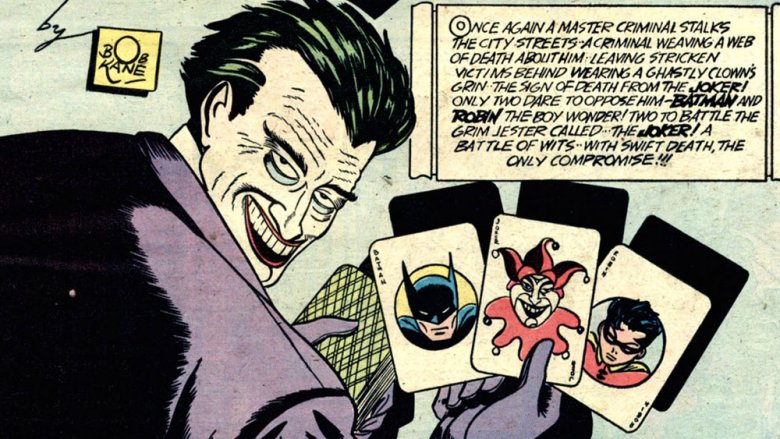

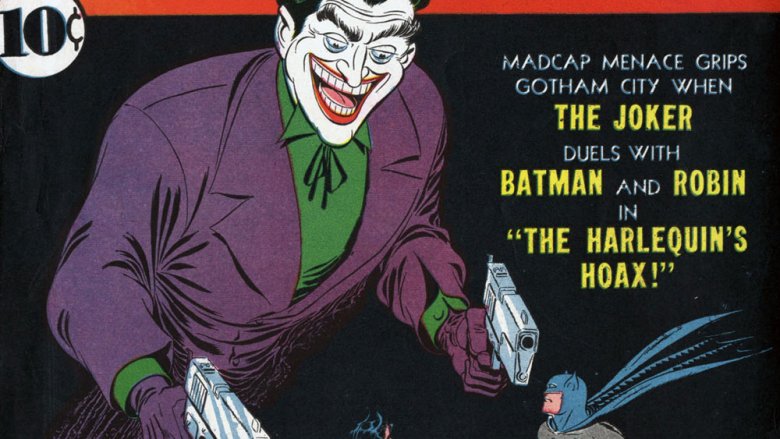

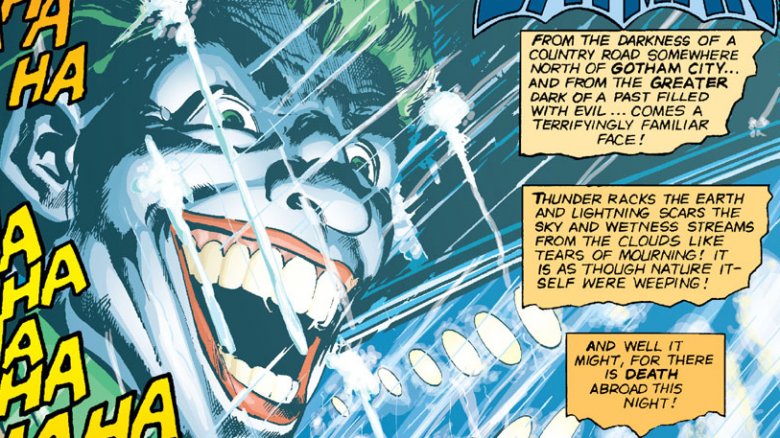

Batman #1 hit the shelves in 1940, and after a quick recap of who Batman was and how he came to be, the first full-length story kicked off with one of the Golden Age's most memorable images: the Joker, looking over his shoulder, directly at the reader, smiling while the caption promises "a web of death" forming around him.

Finger and Robinson had, of course, added in the motif of a playing card, imagery that's such familiar, low-hanging fruit that it almost had to happen in the brand-new superhero genre. It's such a recognizable element that comics have gone back to it time and time again — the Royal Flush Gang, Jack of Hearts, Gambit, you get the idea. Right from that first panel, though, the Joker was unsettling, for the same reason that Veidt's performance was memorable in the film: a total disconnect between emotion and expression. From page one, in a very literal sense, there's something off about him.

And the story, of course, bears that out. The Joker racks up a dozen kills in his first appearance, and when he comes back for his second story later in that same issue, there's a visceral quality to the scenes where he's shouting "I'll kill you!" and trying to stab Batman with a knife that's at odds with the stiff art that's so common in the Golden Age. Clearly, the creators were onto something, even if they didn't realize it. The Joker was originally intended to die at the end of that first story, like most of Batman's early foes did, but editor Whitney Ellsworth decided to keep him around, and the last panel of the Joker's body being hauled away was changed to have the doctors surprised that he'd survived instead.

Boners, blunders, and gimmicks

It wasn't long until the Joker, as a character, ran up against a problem. With the arrival of Robin, the Batman titles had started to skew towards a younger audience, a tactic that was making competing books like Action Comics (starring Superman) and Captain Marvel Adventures (with the character known today as Shazam) extremely profitable for their publishers. A murderous clown who nearly kills Batman with a knife and then breaks into uncontrollable laughter at the idea of his own death is... maybe not something they thought kids would be into.

The Joker stuck around, though. He was already a popular character, and the striking contrast of the smiling, colorful villain and the darker, Dracula-influenced hero was a great visual, even in the years when Batman was also smiling. He just changed to keep up with the times, leaning hard into the clown aesthetic of his personality rather than the serial killer stuff that had been a huge part of his debut.

If you've been on the Internet for more than five minutes, you've probably seen the most famous example of this: a story where the Joker declares that he's going to commit crimes based on history's greatest "boners" (i.e., mistakes), which would turn out to be hilarious once the next century rolled around with a whole new meaning for that word. While it's a popular one to bust out without context, it's actually pretty representative of the Joker stories of the time: entertaining and clever, but not substantially different from any other villain in comics.

The Red Hood

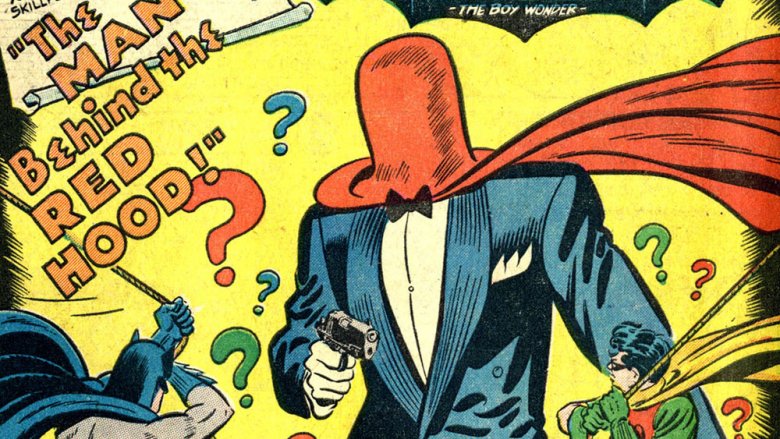

A crucial element that the Joker kept through the sillier years was that he was never given a real name or a definitive origin story, a fact that's actually pretty remarkable in itself. Comics back then were dedicated to explaining every single piece of their mythology, to the point where they'd eventually have Batman encounter the guy who killed his parents, and then later encounter the guy who really killed his parents by hiring the first guy. That story also explains where Batman really got the idea for his costume — his dad had a bat costume that he wore to a costume party — which had already been explained back in 1939.

The closest they ever got came to "explaining" the Joker was when Bill Finger, Lew Sayre Schwartz, and George Roussos gave us "The Man Behind the Red Hood" in 1951. The thing is, that story doesn't actually tell us anything. We never learn the Red Hood's real name, we never see his face. All we find out is that he's had multiple identities, and that there are things in his past that even Batman, the World's Greatest Detective, doesn't know. Even better, we find out that he was willing to leap into a vat of toxic chemicals — which just happened to be next to a playing card manufacturer — rather than be apprehended by the police. Even before he's the Joker, he's got a disregard for human life, even his own.

As an "origin story," "The Man Behind the Red Hood" only served to make the Joker more mysterious. If he wasn't always the Joker, was he even really the Joker now? Were there more identities in his past? Those questions would remain a part of the character for the next 70 years.

Gone and forgotten?

Believe it or not, there was a time when the Joker just wasn't around in the pages of Batman or Detective Comics, but it wasn't because of a lack of popularity, at least not on a large scale. There was one audience for whom the Joker was decidedly unpopular, and while it was an audience of exactly one person, it turned out to be the one that mattered the most: Julius Schwartz, who took over editing Batman and Detective in 1964, "despised the character."

As a result, his role in the core Batman titles dropped off dramatically, with the few appearances he did have coming as a result of the Joker being such a fan-favorite villain on the Batman TV show. When the show ended in 1969, however, Schwartz apparently didn't see any reason to keep him around, and for the next four years — June 1969 to September 1973, to be precise — there weren't any new Joker stories in those two comics.

There were, however, two appearances elsewhere, in books that Schwartz wasn't editing. The first was in Justice League of America, where the Joker proved himself to be a world-class villain by tricking the JLA's sidekick into betraying the team's secrets. The second was in the pages of Brave and the Bold, in a story that opens with the Joker murdering an entire family as they're sitting down to dinner, leading Batman to furiously swear that if the GCPD wanted to take the Joker alive, they'd better find him before Batman did. In retrospect, those are two pretty important turning points. He'd been a homicidal maniac before, but this was the Joker working through psychological terror, murdering innocents for the sole purpose of messing with Batman and setting up a complicated trap.

The Comeback

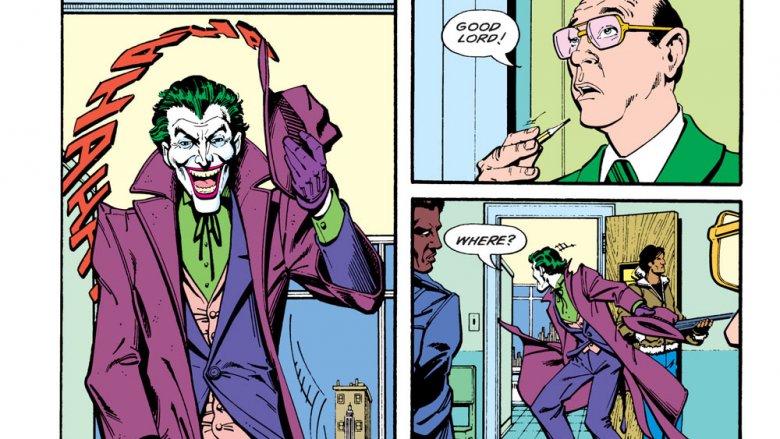

In 1973, Julie Schwartz apparently had a change of heart, or was convinced that four years was long enough to go without a villain that readers still liked. The result was one of the most memorable Batman comics ever: "The Joker's Five-Way Revenge," by Denny O'Neill and Neal Adams.

That team would wind up contributing some pretty huge elements to the Batman mythos — they co-created Ra's al-Ghul and Talia, among others, and O'Neil would himself spend about 15 years as the editor of the Batman comics, bringing over a writer/artist named Frank Miller for an ambitious project about Batman's later years when he left Marvel. Even with all that, though, this might be their most important work. It wasn't just a reintroduction of the Joker, both in-universe and for the readers, it was arguably the single story that "created" the modern Joker. As the title suggests, he's out for revenge — not against Batman, but against his own henchmen.

The story established that Joker had been imprisoned in — and escaped from — "the state hospital from the criminally insane," brought back the poison that had left his victims as smiling corpses back in his first appearance, and, crucially, established that his plans weren't necessarily driven by logic. Only one of the five henchmen targeted in the story had actually betrayed him to the police, but Joker didn't know which one. The solution: kill them all, by poison, bombing, and feeding one to a shark. The Brave and the Bold story may have been a prototype for the ramping up of the Joker's insanity, but this was the foundation on which everything else was built. If the Joker wasn't Batman's true arch-nemesis before then, he certainly was after.

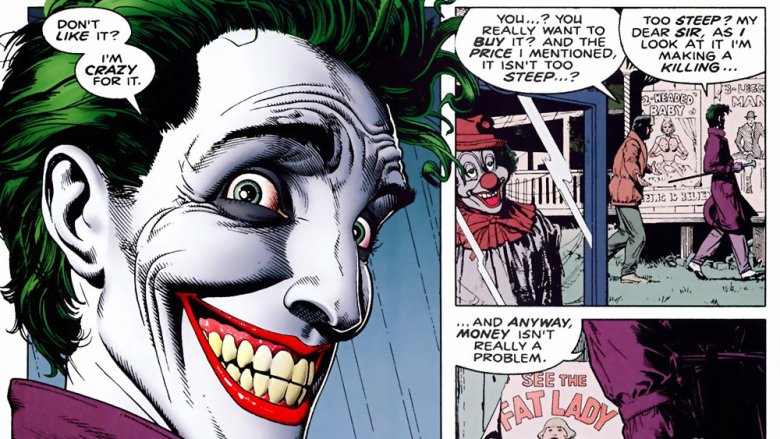

The Laughing Fish

It's worth noting that the revitalization of the Joker and his increasingly unpredictable madness wasn't solely a product of O'Neil and Adams. A few years later, in 1978, Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers, another creative team hired away from Marvel, knocked another definitive Joker story out of the park: "The Laughing Fish." For his part, Rogers' work here is considered some of the all-time best Batman art, with good reason. Unlike a few other artists, he plays the smile as a permanent fixture on the Joker's face rather than just an expression, hearkening back to Veidt and The Man Who Laughs.

At heart, it was an updated retelling of the first Joker story from Batman #1 — the Joker sets off on a string of murders, announcing his targets well in advance to terrorize the city before leaving them with their poisoned smiles — but there was one big twist. Rather than being random death and destruction, the Joker's reason for the murders, or at least the excuse he was using, was that his victims were all city officials who were keeping him from getting a patent on fish, which he had of course poisoned with the same smiling toxin.

It is a bizarre motive, but that's exactly why it works. The other villains might have fixations and obsessions, but the Joker was completely beyond reason. Demanding something so ridiculous from bureaucrats — whose first instinct was to explain the actual reasons why you can't copyright fish instead of running for their lives — was a challenge to the very concept of an ordered world. He quite simply could not be reasoned with, because in his view, reason didn't even exist.

Villain evolution

Throughout the '70s, the Batman comics were on a sort of pendulum, swinging from one extreme (the pop-art camp of the '60s) to the other (gritty, violent street-level crime dramas). He was still a superhero who lived in a world with invisible airplanes and bulletproof flying dogs, but stories like "There is No Hope In Crime Alley" and "To Kill a Legend" had pulled the focus onto the idea of how people deal with tragedies.

That same lens was applied to the villains, too. Throughout the '70s and '80s, and even into the '90s, Batman's gallery of foes went from a solid roster of baddies with great gimmicks and interesting hooks to a group of villains who were reworked into being specific psychological foils for the hero.

Two-Face, for instance, became explicitly cast as a tragic figure who was struggling between his own two extremes of good and evil, and what it was like to look into the mirror and see something that was more like a mask looking back at you. The Riddler had always had a superiority complex, but now it was about proving that Batman, and everything he stood for, could fail. Bane explored the idea of someone with Bruce Wayne's keen mind and gifted athleticism being born into crime, corruption, and poverty instead of a life of privilege. Even the Penguin, who had always hovered between a handful of incongruous gimmicks — Umbrellas! Birds! Tuxedos? — was tweaked into a character who reflected the darker side of wealth, hiding his criminal activities behind an old-money veneer in the same way that Batman hid his crime-fighting behind his own family fortune.

Destined to do this forever

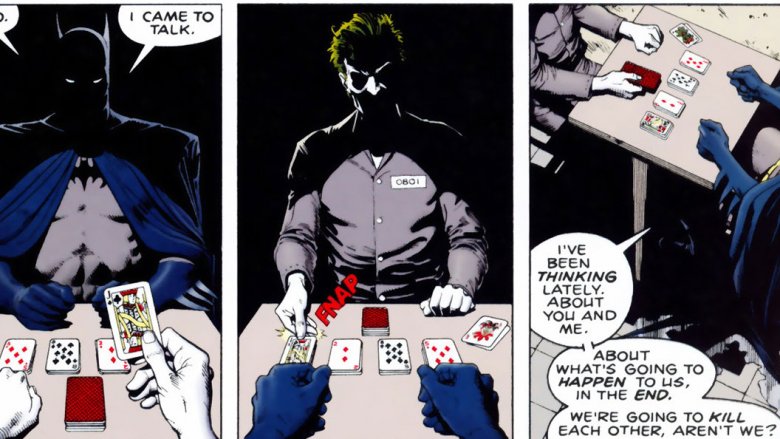

The Joker was ahead of the curve, but the same change was happening with him. He stopped being merely unpredictable, becoming an embodiment of madness and nihilism who represented a moral threat that went far beyond just punching him out and dragging him back to Arkham Asylum. And the thing is, he kind of had to evolve that way, because Batman was undergoing the same change himself.

Say what you will about the "Shark-Repellant Bat-Spray" scene in the '66 movie, but if you get right down to it, it actually is a pretty accurate portrayal of how Batman works as a character. He wasn't alone, either — throughout the past 30 years, there's been a trend of reducing superheroes down to their core essence to keep them consistent across thousands of stories by hundreds of creative teams. Spider-Man is about responsibility. Wonder Woman's about truth. Superman's about hope. Batman was about determination, this unbeatable will to win. He evolved from just having the tagline of "The World's Greatest Detective" into embodying the phrase, becoming the character who was always one step ahead because he had to be — because if he wasn't, people died.

That became the consequence: death. It had always been there, going all the way back to the origin story, but in the '80s, it was codified into the core of the character, and as Batman's definitive arch-nemesis, the Joker evolved to embody it. He is the consequence. He's the crack in the determination. In essence, the Joker is "why not?" and Batman is "because."

Exponential insanity

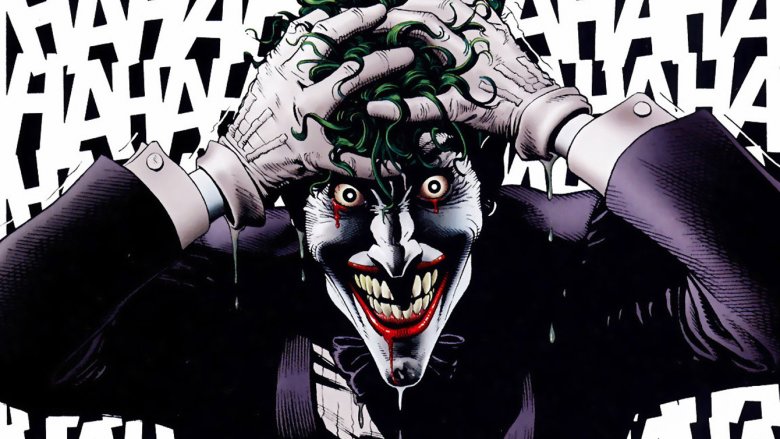

As that evolution was happening, the scale of everything about Batman, including the Joker, was increasing exponentially, quite simply because it had to. If you have a character defined by the idea that he can't fail, you have to keep giving him situations where it's harder and harder to win, and his arch-nemesis has to expand to keep up.

That's why the Joker was the one who killed Robin, which stood for years as Batman's greatest failure. It's why he was the central character in The Killing Joke, where Alan Moore and Brian Bolland go back to that Red Hood story from 1951 and rework it into its own kind of tragedy that paralleled Batman's own tragic origins. And it's why every time he showed up after, those consequences had to keep getting more dire, more destructive, more of an assault on the very concepts that Batman was built on.

There's a line in a story called Batman R.I.P., where a bunch of villains who think they've killed Batman (they haven't) ask the Joker what he thinks. After all, he's the person in the world with the most experience in, well, trying to kill Batman. After telling them that he thinks "Batman crawls out of that shallow grave" and hunts them down, he sums up their relationship: "Every single time I try to think outside his toybox, he builds a new box around me."

That's how the Joker became the twisted, amoral character that we have today. The only real question is how big those boxes can get.