The Hunger Games: The Ballad Of Songbirds And Snakes Review - A Captivating Return To Panem

- A gripping prequel that feels like Andor in its exploration of a rebellion we know will fail

- Thrilling performances from the entire cast

- Feels eerily prescient to current world events

- Snow's transition to unambiguous villain is a little rushed

- Yet again, the love story is the least interesting aspect of a "Hunger Games" movie

Infamously, one of author Suzanne Collins' inspirations for "The Hunger Games" came late one night in the early 2000s when she was home alone and channel surfing, struck by the disparity between reality TV on one network and rolling coverage of the Iraq war on the other. Her novel trilogy and the subsequent film adaptations struck a chord far beyond their original target audience for the prescience of its dystopia, taking a narrative that at first glance felt derivative of "Battle Royale" and expanding on it until it became a borderline political conspiracy thriller.

The two-part adaptation of the divisive final novel, "Mockingjay," ended up tipping the balance of action and governmental mechanics too far in the latter direction for audiences who were primed for high-stakes battles to the death. In many ways, this reaction only validated Collins' world-building even more — it isn't just Panem where people would rather watch gladiatorial battles between children over the dismantling of the entire rotten system. Those who hated the two-part "Mockingjay" finale will likely be equally baffled by the prequel "The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes," another story far less interested in the games themselves than how the groundwork for this authoritarian system was laid.

An Andor-style prequel

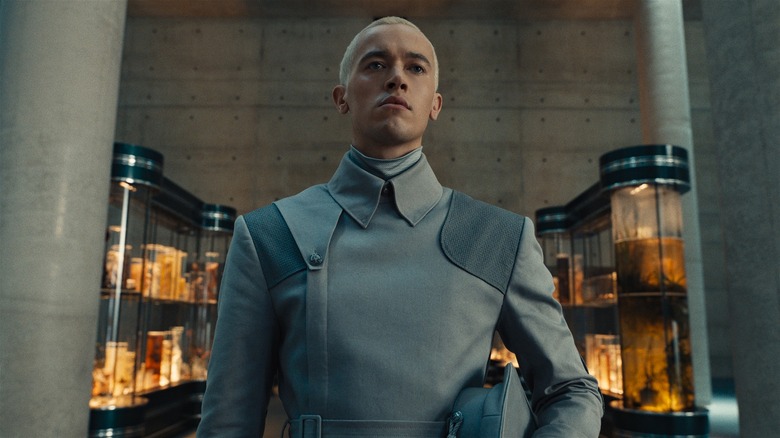

"The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes" is one of the more radical franchise blockbusters to have emerged in quite some time, positively reminiscent of the recent "Star Wars" series "Andor" in how it explores the foundations of a rebellion viewers innately know is doomed to fail. What makes it even more striking, however, is that this is viewed entirely through the eyes of 18-year-old Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth), a character we know will grow up to be the despotic ruler of this world, the franchise's ultimate big bad. He won't threaten to dismantle a system he'll one day rule, and director Francis Lawrence — returning to the world of "The Hunger Games" after directing each of the big-screen sequels — trusts in the intelligence of his young audience enough to be able to explore the nuances of Snow's tyrannical persona, hiding more subtly than you'd expect behind the appearance of a conventional YA protagonist.

Set 64 years before the first novel, "The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes" whisks us into a Panem increasingly wary of the games, which viewers are largely appalled by in the decade since their debut. Told by the creator of the annual ritual — played with a theatrical menace by Peter Dinklage — that this year's contestants will be assigned mentors for the first time, Snow is partnered with a defiant country singer from impoverished District 12, Lucy Gray Baird (Rachel Zegler), an amalgamation of several recognizable icons of the music genre. She's an outspoken menace to authority figures and a voice for the underclasses, like Johnny and June Carter Cash morphed into one, and spotting her ballsy persona, young Snow has an idea to get viewers to tune in for the first time; build the games around the popularity of the contestants, getting to know them in-depth before they begin. Head gamemaker Dr. Gaul (Viola Davis, winningly channeling Tilda Swinton's tyrannical leader from "Snowpiercer") likes the innovation — she only asked for the games to be founded when quizzing her underlings for a cruel punishment that would stop the capitol's "enemies" from uprising against them, and this tweak adds a polished, televisual sheen to the annual atrocities, only normalizing them further.

As with the original trilogy, there's a doomed romance at the center far less interesting than the political maneuvering around it — only this time, screenwriters Michael Lesslie and Michael Arndt are keenly aware that this is the least dramatically engaging aspect of the lead character arcs, using it purely as a jumping off point to expose the limits to Snow's flirtations with revolution. He's much less invested in changing the system than his best friend Sejanus (Josh Andrés Rivera), and the movie is at its most arresting when underlining the ways in which he can't fully commit to fighting for a more equal society. It's here that the film is at its most prescient, as like "Andor," Suzanne Collins and the two adapting screenwriters possess a keen historical awareness, drawing parallels to various authoritarian governments and failed uprisings against them, fleshing out the world beyond the Capitol with a greater depth than the original cinematic tetralogy. Many viewers may be baffled that the games themselves end at the halfway point here — with the film's only spot of comic relief, a wonderful Jason Schwartzman, disappearing along with them — but they're just one part of a rotten system they're keen at exploring in greater depth.

A movie for the moment

There's also a ripped-from-the-headlines urgency to the drama, something which makes itself clear from the moment we see all the young contestants rounded up and kept in a gigantic zoo enclosure, any fightback met with bullets, and pleas from the leaders of the Capitol that this is to be expected from the "enemy." Any violent reaction to them is divorced from years of historical context, reported as an unprovoked remark within their news, knowing that the voices of those in the poorer districts have been oppressed enough by the system that the rich will never hear the other side of the story that has grown up under the shadow of countless crimes against humanity. I don't want to cheapen horrific events in real life by making this parallel more apparent than it needs to be, other than saying it's frightening how much a film set within this warped dystopia chimes with the current moment, right down to the specific methods of dehumanization being used.

The film's third act does falter slightly, not fully sticking the landing as Snow becomes explicitly aware that he has no capacity for bringing about change. This is handled so subtly throughout — largely through throwaway dialogue disregarding "the enemy," even as he's falling for a girl from the heartlands of that enemy teaching him that they're anything but — that the heel-turn into unambiguous villainy seems fairly rushed. If this is also intended as a reset of this universe, an entry-point for viewers too young to have seen the original series when it premiered, this also may prove baffling, undermining the far richer, more complicated character study that came before it.

This is adapted from the last "Hunger Games" novel Suzanne Collins completed, but it reveals that this has one of the richer universes to explore from any of Hollywood's biggest franchises. Immediately preceded by a devastating war and separated from the main films by more than 60 years, there's plenty still left to explore — I certainly hope this ushers in a wave of stand-alone movies in this world, even if this satisfies incredibly well on its own two feet. Every blockbuster should strive for this perfect balance of head and heart.

"The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes" premieres in theaters on November 17.