All The Light We Cannot See: The Biggest Differences Between The Book And The Series

"All the Light We Cannot See" has been slowly making its way from the page to the screen since the book's release in 2014. Anthony's Doerr's sweeping, emotional World War II novel about a blind French girl and a reluctant German soldier in Nazi-occupied France won the Pulitzer Prize in 2015. In 2023, a miniseries from screenwriter Steven Knight ("Peaky Blinders") and director Shawn Levy ("Stranger Things") landed on Netflix.

The story is all about connection, especially between Resistance broadcaster Marie-Laure LeBlanc (Aria Mia Loberti) and the conflicted German soldier Werner Pfennig (Louis Hofmann), a radio expert who risks his life to protect Marie-Laure during the Battle of Saint-Malo. "All the Light We Cannot See" was being lined up as a movie at one stage, but when that failed to materialize, a miniseries was proposed. Naturally, some artistic liberties were taken with the miniseries, but what did the creators change, exactly? These are the biggest differences between the book and the series.

Shortwave 1310 and The Professor's radio show

Taking tools traditionally favored by propagandists and instead using them to spread kindness and reason is a major theme in both the series and book versions of "All the Light We Cannot See." However, the forbidden radio show young Marie-Laure and Werner listen to in their childhood is given a bit more artistic license in the series.

In the series, shortwave 1310 broadcasts a mysterious, magical program late in the evening just for children, hosted by a man known only as "The Professor." Viewers only get to hear bits and pieces of the show, but enough to determine The Professor is speaking poetically about scientific concepts and human capacity for enlightenment. This is a big no-no in Nazi Germany, and the Nazis block the broadcast. Still, The Professor's voice sticks in Marie-Laure and Werner's heads, and both dedicate themselves to following the frequency for the rest of the series.

While the series uses The Professor's words to underscore themes of connection and finding light in times of darkness, the radio show in the book is more explicitly a science program. An episode about the life cycle of coal fascinates both Marie-Laure and Werner, and it links them not just as fellow humans impacted by war, but also as growing young minds intrigued by the natural world. In the book, it's also a little more clear that listening to this — and any radio show forbidden by the Nazis — is an act of defiance.

Jutta's story

Jutta (Luna Wedler), Werner's younger sister, is given very different treatment in the book and the series. Jutta's role and her story is compressed in the series, in which she mostly serves as the voice of reason who warns Werner against listening to forbidden broadcasts for fear of him being scooped up by the Gestapo. In the book, however, Jutta has a significant role to play when it comes to attempting to save her brother from the grip of the Nazis.

In the book, Jutta also listens to forbidden broadcasts on the radio that Werner fixes. Her thirst for foreign knowledge helps keep her opposed to the war and to Nazi ideology, and it inspires her to urge Werner to resist indoctrination when he attends Schulpforta, a state boarding school. Jutta also endures a horrific attack from Russian soldiers, and the story of the book follows her through this attack and into adulthood.

Jutta becomes a math teacher in the book, and she has a child named Max. She even seeks out Marie-Laure in Paris after the war, and the two connect over their shared past. In the series, Werner is able to reach out to Jutta over shortwave 1310 after he finally meets up with Marie-Laure. Jutta weeps, hugs the orphanage radio, and that is the last viewers see of her.

Frederick and Werner's inner turmoil

In the series, Werner is forced to be a German soldier. He risks death every time he defies Nazi orders. As he later tells Etienne (Hugh Laurie), he is tormented by the "bad things" that he's done. Of course, in the series, almost all of Werner's anti-radio task force crimes happen off-screen. Werner is portrayed as a victim of circumstance. There are scenes in the series where he is literally forced to do wicked deeds. However, in the book, Werner's relationship with violence and cruelty is expressed in a more complicated way.

Rather than being forced into attending the brutal National Political Institute of Education at Schulpforta, book-Werner sees this as a positive alternative to dying in the mines, like his father did. At school, Werner befriends Frederick, a character who doesn't make a big dent in the Netflix adaptation. Frederick is smart, sweet, and science-minded, just like Werner. But Frederick is outspoken about his beliefs. He gets beaten almost to death for them, and while Werner doesn't agree with the Nazi youths who hurt Frederick, he keeps himself safe by not speaking out.

Frederick is a major touchstone for Werner's guilt and the first casualty in his life as a Nazi. Werner's conflict over his role in the war and his tolerance of cruelty in favor of his own survival is a major aspect of the book. This is a big missing piece in the Netflix adaptation.

Volkheimer and Clair de Lune

In the series, Marie-Laure is surrounded by allies in her Resistance work. However, when it comes to reluctant German soldiers, Werner is portrayed as a Resistance army of one. His fondness for Marie-Laure's programming and her use of shortwave 1310 endears her to him and ultimately makes him want to protect her, but in the book, it's fellow soldier Frank "The Giant" Volkheimer who really pushes Werner to save Marie-Laure.

Volkheimer has a minimized role in the series. In the book, he is portrayed as a soldier who doesn't necessarily believe in what he's fighting for. When Volkheimer and Werner end up buried under rubble in the Battle of Saint-Malo, Volkheimer hears Marie-Laure playing The Professor's old science programs. The programs contain a piece of classical music that he adores: Claude Debussy's "Clair de Lune."

For all of Volkheimer's bulk and brute strength, he loves classical music. He is so moved by Marie-Laure playing the song that he uses a grenade to blast himself and Werner free. He urges Werner to find the girl, and Werner listens. Sadly, this subplot from the book didn't make it into the series, but the music does — "Clair de Lune" is the song Marie-Laure and Werner dance to in the final scenes of the Netflix adaptation.

Reinhold von Rumpel's mistress

Several new characters were created for the screen adaptation of "All the Light We Cannot See." One of these characters is Sandrina (Andrea Deck), a former florist who becomes the mistress of Reinhold von Rumpel (Lars Eidinger). Reinhold eventually tires of the creature comforts that Sandrina has been providing during wartime. Instead, he wants her to tell him where Marie-Laure lives, because legend has it that her locksmith father stashed the Sea of Flames diamond with his daughter. Reinhold wants the gemstone because it supposedly grants its holder eternal life and he is suffering from some undisclosed disease.

The Sea of Flames storyline is more fleshed out in the book, but the basic idea remains the same in the series: Reinhold wants the sparkler so he can live forever, and he will stop at nothing to get it. Sandrina is there to show viewers just how much people in Nazi-occupied countries had to change in order to survive and how regular people were subjected to Nazi intimidation tactics. Sandrina longs for a different life, and that ultimately sways her. She betrays Marie-Laure and her compatriots so she can save her own skin.

Schmidt and Captain Mueller

The Netflix adaptation invented some new German characters "in order to manifest the evil of the Nazi party, the threat of war, and the encroaching threat on Marie being found in her hiding place," series director Shawn Levy told Entertainment Weekly. Two of these characters are the suspicious Captain Mueller (Jakob Diehl) and the sniveling Schmidt (Felix Kammerer).

Both Schmidt and Mueller suss out Marie-Laure's broadcast signal and the fact that Werner has tried to hide it. They suspect Werner may be working with the Resistance, when really, Werner is just desperate to protect the girl he is falling in love with. Of course, the stories Marie-Laure reads over shortwave 1310 are, in fact, helping the Americans coordinate where to drop their bombs.

Even though Werner is part of a squadron that has murdered rebel broadcasters in the past, Werner now kills for Marie-Laure. He takes out Schmidt first, then Captain Mueller, which would mean certain death should he get caught. While these events don't take place in the book, it's easy to see why they appear in the series — Werner's rebellious attacks for Marie-Laure's sake really up the tension.

Madame Manec's role

In the series, Madame Manec (Marion Bailey) is Etienne's sister, working alongside him in the Resistance, but in the book, she is Etienne's housekeeper and maid. The original version of Madame Manec works with The Old Ladies' Resistance Club and tries to convince the agoraphobic, PTSD-stricken Etienne to aid her. She dies of pneumonia, which spurs Etienne to finally take up her work in her stead. Meanwhile, in the series, Madame Manec dies of a heart attack: Etienne and Marie-Laure return from the oyster grotto to find a dramatic scene full of fire and smoke after Madame Manec dies while cooking.

Etienne weeps over his sister's body, but he insists to Marie-Laure that she only passed on because she knew that the Resistance was finally safe with Etienne, his agoraphobia now healed by Marie-Laure constantly asking him to join her outside. It's a lovely sentiment, but it does make a viewer wonder — if Madame Manec was willing to hold on for Etienne's agoraphobia to clear up before she died, why not wait a few minutes longer for dinner to be ready rather than burning the house down?

Reinhold von Rumpel's death

In both the book and the series, Reinhold von Rumpel gets his just deserts. In the book, the cruel, gem-obsessed sergeant major dies by Werner's hand before he can reach Marie-Laure. She's been broadcasting the fact that von Rumpel is after her, so Werner knows to be at least slightly prepared for this. Von Rumpel initially thinks Werner is also after the Sea of Flames and threatens to shoot him. However, Werner manages to get a fatal shot in, saving Marie-Laure in the process.

It doesn't play out like this in the series, which gives Marie-Laure the honor of vanquishing her own foe. The scenery-chewing Nazi taunts her, threatens to take her hearing, and mocks her with a cruel recounting of her father's death. Marie-Laure withstands the awful man and takes him down with a well-aimed bullet. Werner still gets in on the action by attempting to choke von Rumpel with — what else? — a radio wire.

The Professor's real identity

A major change between the book and the series is the identity of The Professor. While the series makes it clear through Hugh Laurie's unmistakable voice that Marie-Laure's uncle has been The Professor all along, it's a different story in Anthony Doerr's novel.

In the book, Etienne is Marie-Laure's great-uncle. His brother, Marie's grandfather Henri, is The Professor. Together, Henri and Etienne created and broadcast the science program. After Etienne watches Henri die in World War I, he is haunted by the tragedy and ends up broadcasting old recordings of the science program in secret. He becomes agoraphobic and only leaves his home for the first time in decades in an effort to save Marie-Laure from an attack.

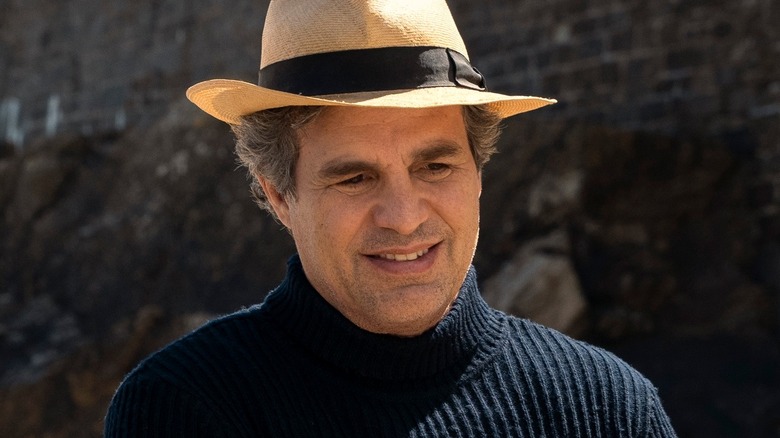

In the series, Etienne is still agoraphobic and still haunted by memories of fighting in World War I, but there is no Henri. Instead, Etienne is The Professor. While book fans may find this change wild, it actually makes sense for a TV adaptation and strengthens the powerful relationship between Etienne and Marie-Laure. It does make us wonder why Daniel LeBlanc (Mark Ruffalo) never told Marie-Laure about The Professor's true identity, though this is perhaps a safety measure.

Daniel LeBlanc's death

"All the Light We Cannot See" is a largely nonlinear story, and that's true of both the book and the series. Even with all the time shifts, it's clear that Marie-Laure is putting out her signal to find her lost father — Daniel went missing on his return to Paris, and she's had no word from him.

The show seems to hint that Daniel could return to Marie's life, as Etienne did before him. However, in her final confrontation with von Rumpel, Daniel's heartbreaking fate is revealed: Von Rumpel describes torturing Daniel for details about the Sea of Flames, then brutally killing him. Why he thinks that emotionally destroying Marie-Laure will get her to reveal the gem's location is unclear.

In the book, Daniel meets a less grisly but equally heartbreaking end. He is intercepted on his way to Paris, captured by German officers and thrown into prison for treason. While there, he writes Marie-Laure several letters, but ultimately dies of pneumonia.

Etienne's end

Etienne gets a hero's death in the "All the Light We Cannot See" series, but he doesn't die in the book — at least, not for a good long time. He survives a bout in prison, reunites with Marie-Laure, and they live together in Paris for the rest of his days. This makes Etienne's story one of the most drastic departures from the book.

While a lot of the Netflix adaptation is designed to build tension, facilitate the action, and tug at the heartstrings, there's an issue with the way Etienne's arc is handled: The changes mean much of Marie-Laure and Etienne's shared interest in science and wonder is lost in the series.

In the book, Etienne survives prison and fully sheds his agoraphobia. He wants (to paraphrase the book) to "live before he dies." Thankfully, this theme remains intact in the series, even if both versions of the story take different routes to get there.

The romantic finale

In the book and the series, Marie-Laure and Werner only spend the final moments of the story together before being separated. In both versions, they share a can of peaches as they sit through the final bombs and wait for the American declaration of liberation. But, in the series, the two also listen to a piece of music significant both to them and to all the children who once tuned in to shortwave 1310: "Clair de Lune." They dance, they share a tender kiss, and then they part ways, possibly forever. It's a lovely moment, but aside from the brief meeting and the can of peaches, it's all fresh for the series.

Shawn Levy told Entertainment Weekly that he actually considered editing the scene out. The director discussed this with Aria Mia Loberti, who insisted that he keep the touch of romance, especially because blind women are historically not shown in romantic on-screen stories. In the same interview, author Anthony Doerr approves of this significant change to his story, saying, "There's a feeling of resolution. What's wrong with that?" While it's perhaps a little Hollywood, the scene works well for the series.

A very different end for Werner

Speaking to The Wrap, director Shawn Levy revealed that while he's a big fan of Anthony Doerr's book, "the outcomes in the epilogue chapters for both Jutta and Werner were shattering." It's for this reason that the ending of the show "is more open-ended than the book," Levy said. In the series, Marie-Laure offers to help Werner escape through a secret passage. Werner declines, because he doesn't want Marie-Laure to be shot for being a Nazi collaborator. As an alternative, she convinces him to surrender to the Americans. The Germans would kill him if they captured him — this way, he at least stands a chance. It's even implied that the two may reunite one day.

In the book, Marie-Laure does help Werner escape through the oyster grotto. Later, he gets captured by the Americans and gets ill in their camp. He wanders out of his medical tent and into a minefield, where he dies in a "fountain of earth." He and Marie-Laure never reunite, unless you count Jutta appearing on Marie-Laure's doorstep with her dead brother's belongings. It's easy to see why Levy wanted a more hopeful ending for the series. "Perhaps there will be purists who react differently," Levy told IndieWire, "but Anthony loves the adaptation."

Marie-Laure's future

The series ends with Marie-Laure throwing the Sea of Flames into the ocean, breaking the apparent curse of the diamond and granting herself a sense of hope for her new life. The end credits roll, along with real footage of Saint-Malo being rebuilt after the war. It's a potent depiction of loss, change, and a tide turning for a remarkable main character. It's also a deviation from Marie-Laure's story in the book, in which Marie-Laure and Etienne move to Paris following the war. Marie-Laure follows the radio program that inspired her and Werner so deeply, becoming a scientist herself. The grown-up Jutta discovers that Marie-Laure works as a scientist at France's National Museum of Natural History, where her father once worked as a locksmith.

The book reveals that Marie-Laure, now a much older woman, is recounting her tale to her young grandson. She and Werner shared a significant moment in time. This moment marks the end of the series, but it's the beginning of the rest of Marie-Laure's life in the book. Regardless of which ending people prefer, director and executive producer Shawn Levy stands by his choices. He told Variety that the story's major themes remain unchanged: "We must be resilient in our humanity, in our kindness and in our optimism, in the face of those darker forces that are tragically as present in 2023 as they were in 1943."