The Untold Truth Of Dune

"Dune" is one of the most important, influential, and popular franchises in the history of science fiction. Beginning as a novel in 1965 by Frank Herbert, the Dune universe spans multiple volumes of books, short stories, comics, games, a TV miniseries, and a pair of film adaptations, released decades apart. At its heart, it's a deep-space saga set thousands of years into a future in which multiple powerful entities vie for control of Arrakis, a desert planet home to the powerful, superpower-giving spice called melange. Here's a look into the vast world of Dune — watch out for Shai-Hulud (or, you know, sandworms.)

The original Dune novel was inspired by the Oregon Dunes

Between the coastal town of Florence, Oregon, and the Pacific Ocean are the Oregon Dunes, massive sand hills that, in the 1950s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture discovered were actually moving. They attempted to use certain breeds of grasses to stabilize and calm the dunes before they could continue to grow, move, and "swallow whole cities, lakes, rivers, and highways," as Frank Herbert's letter to his literary agent breathlessly suggested they eventually could.

Having published a few successful science fiction novels already, Herbert traveled to Florence in 1957 to explore this bizarre scientific phenomenon and to write an article. That piece was never completed, but the concepts of precious natural resources and monstrous sand dunes and what may lay within led to "Dune." After five years of research and writing, Herbert published "Dune World" and "The Prophet of Dune" in serial form in the magazine Analog Science Fiction magazine from 1963 to 1965. The author then compiled it into a single-volume novel, "Dune," which was published by technical book publisher Chilton Books in August 1965 after more than 20 other publishers rejected it.

It took a long time to make it to the movie theater

"Dune" was published in 1965, but it didn't hit the big screen until 1984. For almost that entire span of 20 years, efforts were underway to adapt the book. In 1971, Apjac International, best known for the "Planet of the Apes" movies, acquired the movie rights and offered the director's chair to David Lean, the legendary British filmmaker behind another desert-based movie, "Lawrence of Arabia." Lean passed, as did British director Charles Jarrott ("Anne of the Thousand Days"). While a director was sought out, screenwriters worked on the script and production plans were put into place, but it all fell apart when Apjac head Arthur P. Jacobs died in 1973.

Apjac sold the rights to "Dune" to a group of French investors, who hired avant-garde film and theatrical director Alejandro Jodorwsky as director. While he'd only directed three full-length films at that point, he definitely had the enthusiasm and ambition necessary to direct "Dune" ... and then some. As detailed in the fascinating 2013 documentary "Jodorowsky's Dune," the director planned to make a 14-hour movie with a dream cast including Orson Welles, Mick Jagger, and Salvador Dali, with a soundtrack provided by Pink Floyd. To nail down the production design, Jororowsky consulted such innovative artists as Moebius and H.R. Giger. He also wanted to depict melange, "the spice," as a magical blue sponge and completely change the ending of the novel.

When that project died, the rights were sold to producer Dino De Laurentiis, who hired Ridley Scott to direct. He dropped out because, as he relates in "Ridley Scott: The Making of His Movies," he was ready to film the movie immediately, but it was going to take at least two and half more years of pre-production. Also, his heart wasn't in it, because his older Brother Frank "unexpectedly died of cancer" while he was working on "Dune." Ultimately, the gig went to cult movie icon ("Eraserhead," "Blue Velvet") David Lynch.

The first Dune film was one of the biggest and most disastrous productions in history

"Dune" finally started being committed to film in 1983 at Churubusco Studios in Mexico City. That location was chosen in part because it was adjacent to large swaths of desert that could stand in for the planet Arrakis, and because the Mexican economy was such that it would cost Universal Pictures far less to shoot the movie than it would have cost in the U.S. "In Europe, there was no country with enough stage space and a desert," producer Raffaella De Laurentiis told the New York Times. "In Hollywood, stage rental alone would have cost $20 million." Shooting in L.A., the producer estimates, could have bumped the "Dune" price tag to $75 million; it ultimately cost about $40 million. And filmmakers made sure that every penny counted. To create the intricate worlds of Frank Herbert's novel, one of the biggest film crews of all time was assembled: 900 workers toiled for months to build 70 sets on eight sound stages. More than 200 people alone had to clean three square miles of desert — down on their hands and knees, no less — of scorpions, snakes, and cactuses to replicate the lifeless surface of Arrakis.

The cons of shooting remotely: The studios were infested by cockroaches, regular telephone outages, electricity so spotty that backup generators had to be ready to go at a moment's notice, and a food poisoning epidemic afflicted half the crew at one point. Filming at one location had to be suddenly moved when it was discovered that the ancient volcano bed was actually where locals dumped their dead pets.

The 1984 Dune film was a disaster

Universal hoped "Dune" would be the next "Star Wars," but while it was certainly as imaginative and ambitious as George Lucas's epic, it ended up being a huge disaster. Critics absolutely hated it: Roger Ebert said "Dune" was "a real mess, an incomprehensible, ugly, unstructured, pointless excursion into the murkier realms of one of the most confusing screenplays of all time." It lacked the broad appeal and fun of more popular sci-fi like "Star Wars" — and Universal knew it on some level before the movie was released, distributing hundreds of thousands of vocabulary guides to movie theaters in order to familiarize audiences with the dense world of "Dune" settings, characters, and words. The guides didn't help much—it ultimately earned just $30 million at the box office, not even clearing its $40 million budget. As a result, Frank Herbert's other "Dune" books were never adapted for the big screen.

A lot of misbegotten Dune merchandise was produced

Because "Dune" was a big-budget space-set epic sci-fi movie, a ton of merchandise flooded stores in 1984. After all, "Star Wars" had done it not too long before, and it earned the franchise millions. However, a lot of that merchandise appealed to kids, because "Star Wars" was a movie with plenty for kids to enjoy; "Dune," on the other hand, was decidedly not a kid-friendly movie — it was hardcore science fiction for serious fans only, and it earned a restrictive PG-13 rating from the MPAA. It seems like a bit of Photoshop trickery, but there's a ton of "Dune" stuff gathering dust in basements, garages, and forgotten warehouses that kids didn't want or even knew existed. Various manufacturers paid big bucks for the rights to make "Dune" merchandise such as jigsaw puzzles, paper doll sets, a pop-up book, puffy stickers, bed sheets, party favors, and View-Master slides (which came packaged with a special-edition "Dune"-themed viewing device). Among the strangest "Dune" products was a series of coloring books, which invited kids to add zest to jarring images from the film such as a skin-lesion-covered Baron Harkonnen and the prone, poisoned bodies of Duke Leto Atreides and Piter de Vries.

And in the 1980s, when action figures were big business, "Dune" dolls flopped. LJN Toys released toys in the likenesses of Paul Atreides, Baron Harkonnen, Feyd, Rabbam, Stilgar, and a Sardaukar warrior (plus a Sandworm), while promised figures of Gurney Halleck and Lady Jessica never hit stores.

It inspired a lot of music

"Dune" and its sequels make for a thoughtful, sprawling, imaginative sci-fi epic, and the books were popular in the '60s and '70s, which can mean only one thing: It inspired a lot of progressive rock. In 1977, jazz keyboardist David Matthews released "Dune," inspired by the books. In 1979, experimental German electronic music composer (and Tangerine Dream member) Klaus Schulze released "Dune," an album of the music inspired by the novel. That same year, French electronica pioneer Bernard Szajner (under the name Z) released a "Dune"-themed album called "Visions of Dune." Around the time of the film's release, Iron Maiden included the song "To Tame a Land" on its 1983 album "Piece of Mind," having changed the song from its original title of "Dune," because Herbert wouldn't give permission. In 1999, German metal band Golem released the "Dune"-themed concept album "The 2nd Moon," while two other metal bands have named themselves after the Duneiverse: Shai Hulud and Dune.

There are other versions of the movie

Lynch estimated that his shooting script would translate to a running time of about three hours, but once it was filmed, edited, and effects were added in, "Dune" wound up being well over four. Rightfully seeing that as completely unmarketable, Universal ordered Lynch to cut a bunch of scenes and streamline the plot; because of all that unused footage, rumors have persisted for more than 30 years that there's a special, Lynch-curated "director's cut." There isn't — Universal has approached Lynch, but his displeasure and disappointment in the film has kept him from returning to cobble together another version.

There is, however, a three-hour version of "Dune" with extra scenes added in, assembled without Lynch's involvement for television broadcast. Lynch was so upset that he demanded his name taken off the credits for this version, replaced with the standard Alan Smithee pseudonym for director and the fake name "Judas Booth" for screenwriter — because Universal betrayed him (like Judas did to Jesus) and killed the movie (like John Wilkes Booth did to Abraham Lincoln).

David Lynch regrets directing the 1984 Dune

In a career filled with weird, challenging movies ("Blue Velvet," "The Elephant Man," "Eraserhead") and zero bona fide box office hits, "Dune" is about the only project that writer-director David Lynch says he truly wishes he hadn't made. In fact, he says it even soiled him as an artist.

"I sold out, so it was a slow, dying-the-death and a terrible, terrible experience," he later reflected. "I don't know how it happened, I trusted that it would work out but I was very naive. The wrong move. In those days the maximum length they figured I could have is two hours and 17 minutes, and that's what the film is, so they wouldn't lose a screening a day ... it's money talking and not for the film at all and so it was, like, compacted — and it hurt it, it hurt it."

Lynch later told Extrovert (via Tor) that he only has himself to blame. "I probably shouldn't have done that picture, but I saw tons and tons of possibilities for things I loved, and this was the structure to do them in. There was so much room to create a world."

There were some reboots, and some failed reboots

Regardless of the film's lackluster performance, the "Dune" franchise continued to gather more fans with each passing year. The franchise itself also grew, with a well-received miniseries airing on The Sci-Fi Channel in 2003, and Herbert's son Brian Herbert writing more bestselling "Dune" sequel and prequel novels with Kevin J. Anderson. By 2008, Hollywood once again saw "Dune" as a hot property with a lot of commercial potential. Paramount announced plans for a new version of the first novel, and hired Peter Berg ("Hancock," "Battleship") to direct. A year later, Berg dropped out and Pierre Morel ("Taken") replaced him, but the studio called the whole thing off in March 2011.

Once again, "Dune" refused to die: In 2016, Legendary Entertainment restarted the project again. Denis Villeneuve, the Oscar-nominated director of "Arrival" and "Blade Runner 2049," signed on to direct a new adaptation of Frank Herbert's original novel from 1965. With a budget reportedly around $200 million, it ranks among the most expensive undertakings in Hollywood history — and that's just the beginning, as the project was planned from the start to be split into two movies.

Dune on the moon

Unfortunately, the complicated and complex planetary systems of "Dune" are not real. And unfortunately, there is no melange on Titan, the moon of Saturn. Nevertheless, it's on Titan that "Dune" has become real. As of 2009, the names of planets from the novels are what are officially used to name plains on that moon. (For example: Chusuk Planitia.) A bit closer to home, Apollo 15 astronauts who visited the Earth's moon in 1971 identified and spotted a crater they named ... Dune.

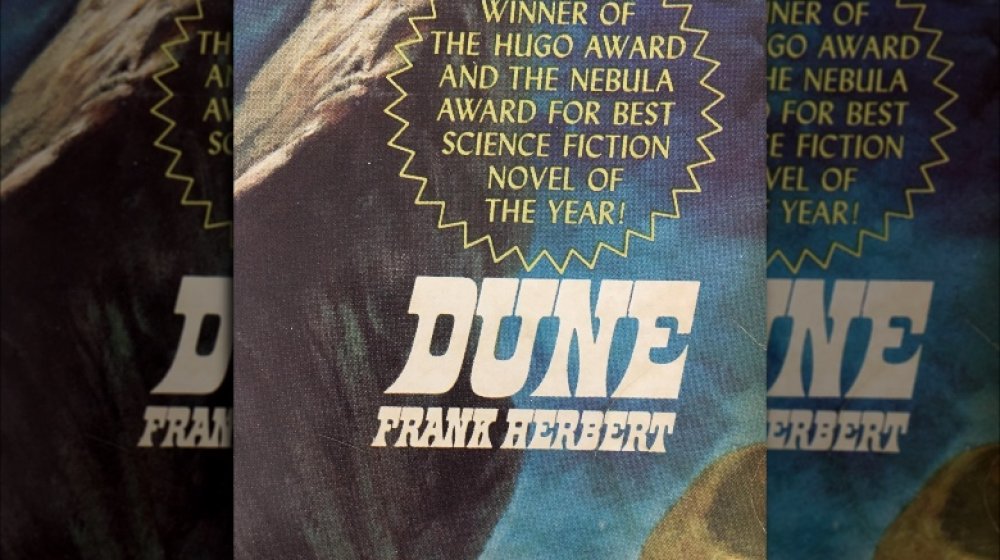

Dune is among the first sci-fi award winners

After years of research and writing, Frank Herbert completed two short science fiction novels — "Dune World" (1963) and "The Prophet of Dune" (1965) that were published in serialized form in Analog Science Fact & Fiction, one of the major outlets for genre stories in the mid-20th century. At the time, short stories dominated sci-fi, because, according to The Guardian, that's what publishers thought readers wanted. That's probably a big reason why "Dune" was rejected by more than 20 publishers before it found a champion in Chilton.

"Dune" proved that there was a market not just for long-form science fiction (it ran well over 400 pages in its first hardback edition in 1965), but high-end science fiction with literary merit. "Dune" is one of the first modern-day sci-fi epics, and was thusly rewarded, capturing the inaugural Nebula Award for Best Novel. Consumers responded in a big way to "Dune" and its descendants. It's still a consistent seller and is one of the most-purchased sci-fi books in history, while sequel "Children of Dune" went down as the first novel in the genre to become a bestseller in hardback form.

Frank Herbert wrote an alternate early Dune novel

"Dune" existed in several permutations before it finally became the lengthy novel published in 1965. Author Frank Herbert carefully combined two smaller, serialized novels, "Dune World" and "The Prophet of Dune," into one, although that all strayed from his first foray into the world of interstellar spirituality and sand worms, a project he called "Spice Planet." While sifting through the mountains of documents and notes Herbert left behind after his death in 1986, son Brian Herbert (and his writing partner, Kevin J. Anderson) discovered an outline, scene descriptions, and character notes for this never-published (let alone seen) alternate iteration of the original "Dune."

In 2005, Brian Herbert and Anderson, who have kept the "Dune" literary franchise alive with various books and stories, used Frank Herbert's guide and composed a complete manuscript for "Spice Planet." Along with original short stories written by the duo, the novella was published in the "Dune" ephemera collection "The Road to Dune." Reading like both a prequel and offshoot of Frank Herbert's "Dune," "Spice Planet" includes familiar character names and locations — and involves the pursuit of a powerful substance called "Spice" — but otherwise consists of long-ago abandoned plot threads.

Lots of major actors didn't get cast in Dune

Pre-production on the 1984 "Dune," including the months it took writer-director David Lynch to adapt Frank Herbert's novel into a screenplay, took a very long time, and filmmakers wanted to make sure they cast the perfect performers to portray the potentially lucrative franchise's already well-known character. Glenn Close turned down the role of Jessica, believing that the character was a "cliche" of a helpless woman. Aldo Ray was actually cast as Gurney Halleck and reported to the set, but was soon dismissed and replaced by Patrick Stewart. Kenneth Branagh auditioned for the lead role of Paul Atreides, but lost out to newcomer Kyle MacLachlan. His future partner, Helena Bonham Carter, was also nearly a part of the "Dune" cast. She'd landed the role of Princess Irulan, but due to a scheduling conflict on "A Room with a View," she had to quit the sci-fi epic, leaving the door open for Virginia Madsen to take over.

The baliset is a real instrument

Although "Dune" is set among sophisticated planets in the distant future, the entertainment options of its residents have a distinctively ancient and rustic sensibility. Gurney Halleck is a major figure in the life of Paul Atreides, a warrior, teacher, and ally who loved to perform old, minstrel-style ballads to entertain guests and associates, all while accompanying himself on a long, nine-stringed instrument called the baliset. Something of a cross between a guitar and a zither, it provided enough music to help Halleck emphasize his proverbs, scripture readings, and lyrics.

In the 1984 film version of "Dune," Patrick Stewart plays Halleck — and the baliset. It was mentioned by name in Frank Herbert's original "Dune" novel, but filmmakers took a real (although obscure) Earth instrument and painted it gold. The baliset is actually a Chapman Stick, a fretboard-based, elaborately strung, strummable wooden instrument invented by musician Emmett Chapman. In 1985, Chapman released "Parallel Galaxy," an album of Chapman Stick compositions, which includes "Backyard," heard in the "Dune" movie — with Stewart miming playing to Chapman's recording.

Sean Young nearly blew her chance to be in Dune

At the time that "Dune" was filmed in the early 1980s, Sean Young was one of the biggest new stars in Hollywood thanks to prominent roles in the hit comedy "Stripes" and the sci-fi classic "Blade Runner." She signed on to play Chani Kynes, a Fremen warrior in "Dune" — but she nearly missed out on the role.

According to "The Making of Dune," Young's agency set up a meeting in New York City with director David Lynch and producer Raffaella De Laurentiis, but then forgot to tell Young about it. On the day it was scheduled, she hopped a flight to California to go meet about another film. Meanwhile, Lynch and De Laurentiis missed their flight to the west coast because they'd been waiting around for no-show Young. The actor, director, and producer all wound up on the same plane, and De Laurentiis asked a flight attendant if Young, whom she'd never met or seen, was an actor. "She is," the worker reportedly said. "Her name is Sean Young." De Laurentiis confronted Young, telling her that the agency said she refused the audition, which simply wasn't true. The trio cleared the air over drinks. "I sit with her and David and we all start drinking champagne," De Laurentiis recalled. "By the time we arrived in L.A., we were roaring drunk." Young got the part, of course.

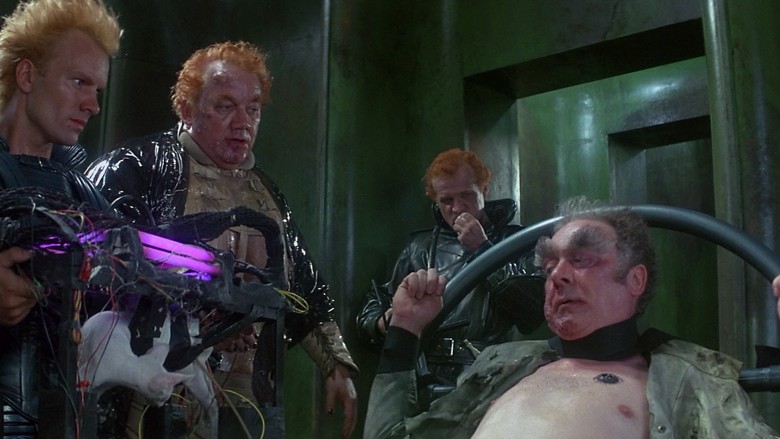

Juergen Prochnow was gravely injured on the set of Dune

For the role of House Atreides patriarch Duke Leto Atreides, "Dune" writer-director David Lynch cast German actor Jürgen Prochnow, the breakout star of the 1981 World War II submarine thriller "Das Boot." According to "The Making of Dune," the last scene Prochnow had to film was a drug-induced nightmare sequence in which he lays unconscious on a stretcher while the wicked Baron Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan) crudely shoves his fingers into a facial wound, expelling spooky green gas. To bring this concept to life, the "Dune" special effects team created a fake cheek out of rubber and makeup, stuck it to Prochnow's face, and attached a tube that ran behind the actor's ear and onto the stretcher. Off-camera, a tech would pump green smoke into the device that would plume out when McMillan prodded it. The crew tested the effect on a dummy and Prochnow before cameras rolled. When it came time to film, McMillan did what he was supposed to do, sticking his fingers into the wound, and the smoke came out. Something had gone wrong, however, because Prochnow ran off the set, clutching his face.

An investigation revealed that the device had malfunctioned. It hadn't been properly sealed, and hot smoke from a test had built up inside the fake cheek before McMillan tore it open, resulting in near-molten goo spilling onto Prochnow's face. He suffered first and second degree burns in the accident.

David Lynch's Dune was supposed to be a trilogy

"Dune" was obviously supposed to be a franchise-starter, a new blockbuster series to rival other sci-fi brands like "Star Wars" and "Star Trek." Its success was so assured that before the film's theatrical release in 1984, star Kyle MacLachlan signed a contract to appear in four more films in the "Dune" cinematic universe (even though his character, Paul Atreides, only figured into three more "Dune" source novels). Virginia Madsen, who landed the small role of Princess Irulan, told "The Kevin Pollak Chat Show" that she'd signed a deal to reprise the role in two more films. "They thought they were gonna make 'Star Wars' for grown-ups," she said. "And it didn't work out that way." When "Dune" was greeted with critical shrugs and less-than-huge numbers at the box office — a $30 million total run, against a $40 million budget — plans for more movies were canceled. "Dune" screenwriter-director David Lynch was already deep into the screenplay for the next movie in the series, based on Frank Herbert's "Dune Messiah," which was subsequently abandoned.

Could the new Dune be the new Star Wars?

Virginia Madsen, part of the cast of the 1984 film adaptation of "Dune," claimed in an interview that filmmakers had attempted to make "'Star Wars' for grown-ups." That's the exact same approach that writer-director Denis Villeneuve took when he set out to bring "Dune" to the screen again, more than three decades after that ill-fated attempt. "The ambition is to do the 'Star Wars' movie I never saw," Villeneuve told Fandom. "In a way, it's 'Star Wars' for adults." (Ironically, 'Star Wars' began as a riff on "Dune." George Lucas's first drafts of the script that would become 1977's "Star Wars: A New Hope" contained fighting bloodline and a princess who guarded not the plans for a Death Star, but something called "aura spice.") The cinematographer on his new "Dune" films? Grieg Fraser, who had the same job on the "Star Wars" spinoff "Rogue One," a film Villeneuve enjoyed.

"Dune" is a passion project for the director, who told press that in adapting the work correctly, he dealt "with the pressure of the dreams" he had as a teenager, picturing the world of "Dune" in his head as he read Frank Herbert's novel. Still, when Warner Bros. wanted him to direct, he agreed to do so if two conditions were met: "Dune" had to be split into two films, and the crew would film the Arrakis scenes in a real desert.

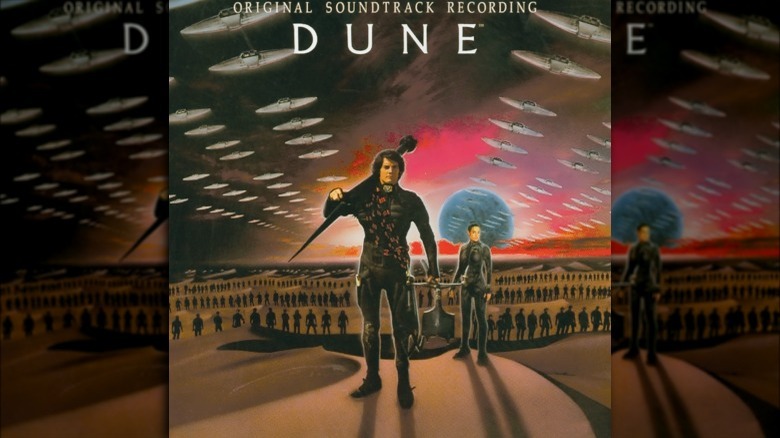

A major rock band recorded the score for the first Dune film

Rather than seek out an orchestral composer to create and conduct the score for the original "Dune" film from 1984, filmmakers used rock band Toto to source the movie's spooky, futuristic, synth-based music. The group, consisting of successful Los Angeles session musicians, was just coming off a career peak, winning the Album of the Year Grammy Award in 1983 for "Toto IV," which included the smash hits "Rosanna" and "Africa." The band was at a crossroads when it came time to record the "Dune" music, with singer Bobby Kimball having just departed and the group deciding to score David Lynch's sci-fi adaptation instead of another gig it had been offered: recording the soundtrack to "Footloose." We probably would have made more money with that, but hey, what can I say?" Toto guitarist Steve Lukather told Westword, adding that his band "did all of the music except for a 30-second part that Brian Eno did. He got all the press."

Nevertheless, the album flopped. Released back-to-back with Toto's fifth studio album "Isolation," the "Dune" soundtrack tanked almost as hard as the movie did, peaking at #168 on the Billboard album chart and soon falling out of print for decades. According to Vintage Guitar (via Toto99), members of the group saw the film at its premiere and called it a "turkey" and privately took to referring to the movie as "Doom."

Dune leans heavily on an older, obscure history text

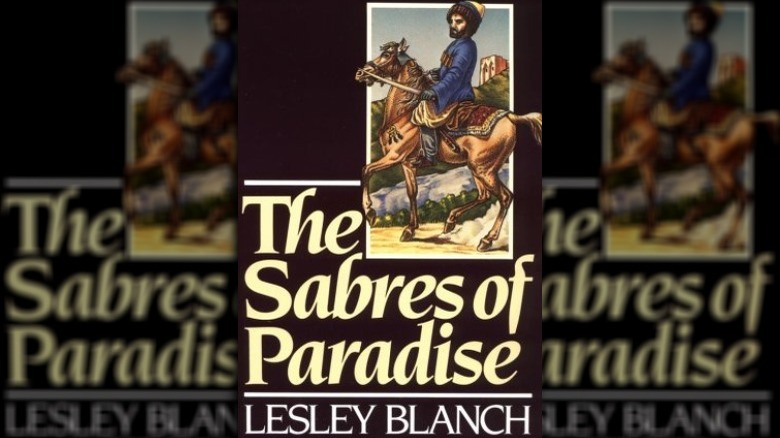

Frank Herbert was chiefly inspired by the sand dunes off the Oregon coast, but according to the Los Angeles Review of Books, he also ran with elements laid out in a now obscure book published in 1960 called "The Sabres of Paradise." Written by Lesley Blanch, an English author best known for travel writing and romance novels, it's a dense and epic exploration of the life of Imam Shamyl, who united under the Islam faith previously opposed groups in the North Caucasus region of Asia, and who led a two-decades-long resistance movement against imperialist Russian forces in the mid-19th century. Blanch peppers the work with words from Chakobsa, a Caucasian language, and a few examples show up in "Dune" — kanly, a term meaning "blood feud," appears in Herbert's novel with the same definition, and kindjal, a common weapon, is the name of a popular knife among the elite in "Dune." When protagonist Paul Atreides takes up with a desert tribe whose ways are similar to that of Caucasus warrior groups, he resides at Sietch Tabr — both words mean "camp" in the language of the Russian forces on the other side.

Herbert even took a whole line from "The Sabres of Paradise." A fight trainer tells Paul Atreides to use style in his swordplay as "killing with the tip lacks artistry." In Blanch's work, she wrote that Caucasians believed that "to kill with the point lacked artistry."