The Untold Truth Of Stephen King

With a number of film and television adaptations currently in development, it's tempting to say that Stephen King is enjoying a bit of a renaissance. But it's not like he's ever gone anywhere—the man has been scaring our pants off for over 40 years, and since 2010 alone, he's published no fewer than nine novels and two short story collections. As we look forward to all of the awesome King-related media coming our way, it seems like a good time to delve a little deeper into the life of the merchant of nightmares. Here's the untold truth of America's boogeyman, Stephen King—one of the most beloved (and feared) authors of our time.

He witnessed a friend's death as a child

It's certainly true that major events in childhood can have an effect on one's personality as an adult, and King has mentioned an incident from his own early years that seems like it could explain a lot. In his non-fiction book Danse Macabre, he recounts a story his mother told him—King has no memory of what happened—when she allowed four-year-old Stephen to go to a friend's house to play, and he returned alone an hour later obviously in shock and refusing to speak. She later discovered that his friend had been struck by a train and killed, and King was likely a witness to either the accident or its aftermath.

It's easy to see how such a traumatic event could shape a young mind in strange ways, but the most immediate evidence of its influence is in the novella The Body, one of King's most personal works and the basis for the film Stand By Me. The plot revolves around a group of young boys searching for the dead body of a peer, and it also contains a harrowing sequence involving a train. For his part, King mostly dismisses the idea that the incident is in some way responsible for his future career as a "shoot-from-the-hip psychological judgment," and he may have a point—but when the four young protagonists of The Body find what they're looking for, his vivid description may convince you otherwise.

His wife rescued his first novel from the trash

A struggling writer at the age of 26, King eked out a living as a schoolteacher, supplementing his income by publishing the odd short story in horror magazines (most of which would later be collected and reissued as books after he made his commercial breakthrough). That all changed in 1974, when his debut novel Carrie—about a withdrawn, telekinetic teen girl who attends the most intense prom in history—made him a household name practically overnight and shook up the horror fiction industry. The paperback rights were sold for a ridiculous $400,000, roughly $2,000,000 in today's money—but the first draft might have been thrown out with the garbage if not for King's wife Tabitha.

"I couldn't see wasting two weeks, maybe even a month, creating (something) I didn't like and wouldn't be able to sell. So I threw it away," he recounted in his book On Writing. "The next night, when I came home from school, Tabby had the pages... She wanted to know the rest of the story. I told her I didn't know (anything) about high school girls. She said she'd help me with that part... I did have something there. Like a whole career. Tabby somehow knew it, and by the time I had piled up 50 single-spaced pages, I knew it, too."

An alternate career

Carrie was followed by two more undisputed classics, Salem's Lot and The Shining, and by 1977 King had accrued a startling amount of fame and success. In fact, he was beginning to wonder if his sudden fame might be driving his sales more than the quality of his work, and decided to test his theory by essentially trying to build a career all over again.

King has always been prolific and by this time already had a substantial backlog, but was publishing only one novel per year, as was the industry standard. So in 1977, he published the novel Rage in paperback under the pseudonym Richard Bachman, convincing the publisher to keep his secret under wraps. Four more novels under the pen name followed over the next several years: The Long Walk, Roadwork, The Running Man, and in 1985, Thinner—the one that finally outed him as Bachman.

Some astute fans noticed similarities between the works of the two authors, and Thinner strongly aroused the suspicions of an intrepid fanzine owner who discovered that the copyrights for the novels were registered to King's agent (and one to the man himself). King finally ended the ruse (scrapping his plans to release Misery under the Bachman name) and published the collected works in a volume titled The Bachman Books. While two further novels—The Regulators and Blaze—have since been published under the name, King refers to these as "posthumous" works, as Bachman died in 1985... of "cancer of the pseudonym."

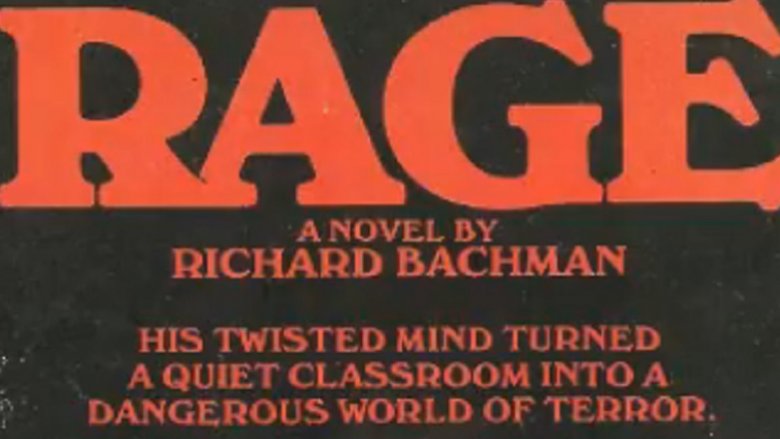

One of his stories is out of print due to real-life horror

King wrote what would become Richard Bachman's debut while still in high school at the age of 18, which makes its plot all the more disturbing. It's the story of Charlie, a severely emotionally troubled boy who brings a gun to school one day, kills a teacher, and takes a class hostage—a scenario that unfortunately has come to have a great deal more resonance in current times.

King has acknowledged this, writing in a Kindle essay, "I suppose if it had been written today, and some high school English teacher had seen it, he would have rushed the manuscript to the guidance counselor and I would have found myself in therapy posthaste...But 1965 was a different world, one where you didn't have to take off your shoes before boarding a plane and there were no metal detectors at the entrances to high schools." Between 1988 and 1997, four individuals either confessed to being influenced by the book or were found to have a copy of it, prompting King to request that his editors remove it from publication permanently, including future printings of The Bachman Books.

He can't stand Kubrick's The Shining

Most everyone agrees that Stanley Kubrick's The Shining is among the greatest adaptations of King's works—everyone, that is, except King himself, who's gone on record many times saying that while he thinks Kubrick was a great filmmaker and The Shining looks fantastic, the director tweaked details unnecessarily, got the lead roles completely wrong, and basically misinterpreted the meaning of the entire novel.

In an interview with Deadline, King described the movie as "a big, beautiful Cadillac with no engine," complaining that the character of Jack Torrance had "no arc at all... all he does is get crazier" as opposed to the slow descent into madness by a fundamentally decent man portrayed in the novel. But he reserved his harshest opinions for Kubrick's interpretation of Wendy Torrance as played by Shelley Duvall, saying she's "really one of the most misogynistic characters ever put on film. She's basically just there to scream and be stupid and that's not the woman that I wrote about."

In fact, King has spoken often and at length about the disconnect between the highly personal nature of his novel and the detached feel of the film. He even went so far as to re-adapt the novel himself into a little-like 1997 TV miniseries—and offered poor, doomed Jack a measure of redemption in his belated sequel to The Shining, 2013's Doctor Sleep.

He doesn't remember writing one of his novels

By the late '70s, King had an alcohol problem that was growing in direct proportion to his success. Cocaine would soon become an issue as well, and he's made no secret of the fact that much of his early output was produced through a substance-fueled haze. In fact, much of this work—from the bloodsucking vampires of Salem's Lot to The Shining's alcoholic Jack Torrance—can be seen as a metaphorical examination of King's own struggles. None more so than 1981's Cujo, a novel that works as an overt, extended metaphor for the rampaging, blind beast of addiction—and one that King can literally not remember writing.

In On Writing, he admitted he could "barely remember writing" Cujo, adding, "I don't say that with pride or shame, only with a vague sense of sorrow and loss. I like that book. I wish I could remember enjoying the good parts as I put them down on the page." He's also stated that Misery is about cocaine—"(his) number one fan"—and that 1987's Tommyknockers was "an awful book... the last one I wrote before I cleaned up my act." He overcame his addictions in the late '80s and has been sober ever since.

He wrote and directed a movie on cocaine

1986's Maximum Overdrive is one of the craziest things ever put to film, and with good reason. The main thrust of the story was taken from a slight 20-page story called "Trucks" that King originally published in a magazine in 1973 (and which later showed up in his first short story collection, Night Shift). But the film—in which all of the world's machines decide that they've had it with humanity—is distinctly the result of many poor decisions.

The project was conceived as King's drug habit approached critical mass, and though he'd never directed anything before, he got it into his head that he was the man for the job, and producer Dino Di Laurentiis inexplicably agreed. Cast and crew noticed King's boundless energy and childlike behavior, which King himself later attributed to his being "coked out of (his) mind," and the proof is definitely in the finished film—which is to say it's fun, manic, and off in a lot of really weird ways. When asked why he's never directed a film since, he bluntly responded, "Go watch Maximum Overdrive."

His entire family are authors

King is sensibly still married to the woman who rescued his career from the trash, and it's no wonder that she knew a promising work when she saw one: she's gone on to become a successful novelist in her own right, starting with her debut novel Small World in 1981. While the Kings don't often tread similar thematic territory, the same can't necessarily be said of sons Owen and Joseph, who amazingly are also enjoying enviable literary careers.

Owen has published an assortment of works of fiction on his own, and also collaborated with his dad on the forthcoming novel Sleeping Beauties. But his brother, who writes under the pen name Joe Hill, has made a name for himself as a major talent. His breakthrough 2005 short story collection 20th Century Ghosts won the Bram Stoker Award for horror literature, and subsequent novels such as Heart-Shaped Box and Horns (which was adapted into a feature film starring Daniel Radcliffe) have proven that the ability to bring the creepy truly does run in the family. He's also behind the acclaimed horror comic book series Locke and Key, which is currently in development as a series for Hulu.

He played in a rock band with other writers

Any fan of King's novels will know that he has an enduring fascination with rock and roll, often using songs as plot points or quoting them directly. He personally recruited AC/DC to score Maximum Overdrive, and once even wrote a short story in which a couple is menaced by dead rock stars. It's enough to make you think he's a bit of a rock star wannabe—which perfectly describes the rest of his former band.

For 20 years, King played guitar in the self-deprecatingly named Rock Bottom Remainders, an outfit that Bruce Springsteen once described as being almost as good as a lousy garage band. Other members included novelists Scott Turow (Presumed Innocent) and Amy Tan (The Joy Luck Club) along with the great humorist Dave Barry. The band called it quits after their "Past Our Bedtime" tour in 2012, and Barry offered a typically wry explanation for the breakup: "We've gotten as good as we're ever going to get... you can't get any better. Well, you actually can get a lot better. But we can't get any better. We're up to almost four chords now, and the Beatles quit at that point, I'm pretty sure."

The Dark Tower novels tie his work together

In 1978, King started publishing a series of short stories in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction that would eventually be collected for the 1982 hardcover volume The Gunslinger. At a relatively short 384 pages, it laid the foundation for the work that would eventually grow into King's magnum opus—the Dark Tower series, which currently consists of eight novels, a novella, and a feature film, with more on the way. It's the story of a lone Gunslinger, the last of his kind, struggling to reach the titular Tower—the nexus of all realities, which holds the fabric of space and time together. Fittingly, the series serves the same purpose for King's fictional universe.

Many of King's works recycle the same settings (such as the fictional towns of Derry and Castle Rock) and characters (such as the psychic Danny Torrance of The Shining and Doctor Sleep), and the Dark Tower series makes it clear that many of King's novels and short stories are connected. Several important characters, including the priest Donald Callahan from Salem's Lot and doomed child Patrick Danville from Insomnia, make appearances in the series—as does one of King's most terrifying villains ever, The Stand's Randall Flagg. The sprawling epic incorporates genres from Western to horror to sci-fi, making it difficult to adapt. But after years of false starts, the Idris Elba-starring The Dark Tower finally arrived in theaters in 2017—although it's more of a sequel to the book series than an adaptation.

It's all connected

After reading enough Stephen King books, you soon realize how interconnected many of his stories are—and It is no exception. The Shawshank State Penitentiary (from The Shawshank Redemption) is mentioned multiple times in It, while in The Tommyknockers, a character driving through Derry spots Pennywise watching him from an open manhole. Later in life, It's Ben Hanscom lives in Hemingford Home, Nebraska—which is also the home of Mother Abigail in The Stand. And Dick Hallorann (from The Shining) saved a man from The Black Spot fire when he was younger. That man became the father of Mike Hanlon, who sees a flashback vision of the fire in It.

Still not enough for you? An adult Henry Bowers from escapes from the Juniper Hill Asylum (mentioned in a number of King works), and is driven by the corpse of Belch Huggins back to Derry in a red 1958 Plymouth Fury (as seen in Christine). When an alien goes to Derry to infect the water supply in Dreamcatcher, he finds the water tower destroyed (which happens at the end of It) and in its place a memorial to all of Pennywise's victims.

In 11/22/63, the main character happens upon Bev Marsh and Richie Tozier playing in the Barrens. When he asks about a recent crime in the town, Bev cryptically remarks, "that wasn't the clown." And the mystical turtle Maturin (who holds the world on his back) features in both It and in The Dark Tower series. Of course, the connections don't stop there. With Stephen King, there's always more.

Real clowns hate Pennywise

While it's fair to say that the fear of clowns dates back to well before the publication of It in 1986, there's no question that the 1990 miniseries adaptation with Tim Curry as Pennywise (which aired on primetime television) introduced that fear to a new generation. When the new movie adaptation was first announced, a resurgence in the "scary clown" phobia came along with it—a phenomenon that professional clowns lay firmly at King's feet. "The clowns are pissed at me," he tweeted in April 2017, not long after a nationwide rash of pranksters in clown masks caused a spike of calls to police and a subsequent media frenzy.

For their part, professional clowns have taken it in stride, but they aren't shy about blaming King for their problems. World Clown Association president Pam Moody says that members have "had school shows and library shows that were canceled," and she knows of at least one professional clown that arrived at a show to find herself surrounded by four police officers after someone called in a clown sighting.

"It all started with the original It," Moody claims. In his defense, King noted in his tweet that "kids have always been scared of clowns. Don't kill the messengers for the message." While that's true, there's no question that Bill Skarsgård's terrifying portrayal of Pennywise in the 2017 film will be instilling clown phobia in audiences for years to come.