The Fabelmans Review: Spielberg Delivers Laughs, Tears, And Cheers

- A love letter to cinema

- Amazingly acted family drama

- More comedy than expected

- Its many great parts could have come together better

It seems the combination of Alfonso Cuaron's success with 2018's "Roma" and increased personal self-reflection during the COVID-19 lockdowns has led to basically every major director doing their own semi-autobiographical movies generally focusing on semi-fictionalized versions of their childhood. Kenneth Branagh's "Belfast" won the Oscar for best original screenplay. Netflix released Paolo Sorrentino's "The Hand of God" and Richard Linklater's "Apollo 10 1/2: A Space Age Childhood." James Gray's "Armageddon Time" is coming soon, and going outside of strictly childhood-centric autofiction, there's also Alejandro G. Iñárritu's filmmaker dramedy "Bardo (or False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths)."

The most eagerly anticipated entry in this post-"Roma" trend, however, is, easily, "The Fabelmans." The reason for the hype is easy to understand: It's a Steven Spielberg movie. Now 75 years old, the genius who gave us "Jaws," "E.T.," and "Schindler's List," to name a few, has made a movie on the childhood experiences that led him to become the filmmaker we know and love. "The Fabelmans" is only the third movie the world's most famous filmmaker wrote as well as directed (the others being "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" and "A.I.: Artificial Intelligence"). He shares the writing credit with Tony Kushner, the playwright who's reinvigorated the director's best recent work from "Munich" to "West Side Story."

Premiering at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival in advance of its November theatrical release, "The Fabelmans" lives up to the hype. If it's not Spielberg's absolute best or most narratively cohesive film, it's still the work of a master filmmaker who knows his craft better than almost anyone else and is using it to go deeply personal without sacrificing the sense of playful wonder that made audiences love his early blockbusters.

The Fabelmans explains Steven Spielberg's psychology

There are certain recurring themes in Steven Spielberg's filmography that come from a personal place. There's a love of special effects and spectacle, obviously, and there are also all those plots involving divorces or absent parents, as well as an evolving exploration of Jewish identity. The memoir-like structure of "The Fabelmans" recounts various stories from Spielberg's coming of age in the 1950s and '60s that formed the basis for his various obsessions over his career.

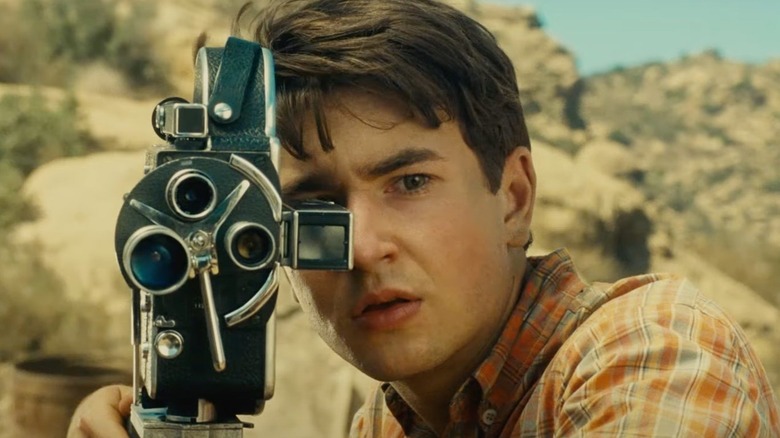

At the tender age of seven, Sammy Fabelman (Mateo Zoryna Francis-Deford), Spielberg's fictionalized equivalent in the movie, is introduced while going to the movies for the first time with his family to see Cecil B. DeMille's "The Greatest Show on Earth." A scene of a train crash terrifies but also fascinates the young boy; he asks for toy trains for Hanukkah and spends his time repeatedly crashing them. While his computer scientist father Burt (Paul Dano) disapproves of all this destructive play, his more artistically-inclined mother Mitzi (Michelle Williams) lends him a camera to film these crashes so he can watch them repeatedly. Thus begins a passion that Sammy continues to hone as a teenager (now played by Gabriel LaBelle), collaborating with his sisters and fellow Boy Scouts to put together Westerns and war movies with homemade special effects.

The Fabelman family moves around a lot for the sake of Burt's advancing tech career, which is something Mitzi can't stand. She is struggling with various mental health issues, something which Sammy is scared to recognize within himself, and she also turns out to be far more fond of Burt's much cooler co-worker and the kids' surrogate "uncle" Bennie (Seth Rogen) than her frustrating husband. The dissolution of Burt and Mitzi's marriage — especially how it impacts Sammy and his sisters — is the source of the greatest tension in the film. All the actors are great, but it's Michelle Williams who has the most challenging role, and she completely sells both her big dramatic breakdowns and the subtler moments of joy and sadness.

It's possibly his funniest film

Though Steven Spielberg films often have comic relief in them, he's not typically thought of as a comedy director. Indeed, one of his most comedically-focused films, "1941," was also one of his biggest flops. "The Fabelmans" is being sold mostly on its mix of movie-loving romanticism and tear-jerking family drama, but it's also, in large part, a comedy. There's a monkey, snarky sisters, special effects humor, Seth Rogen doing his signature laugh, and absolutely hilarious single-scene performances from Judd Hirsch and David Lynch. Even the final shot of the movie is itself a joke that at once has little to do with and everything to do with the rest of the movie.

The funniest sections of "The Fabelmans" center around Sammy in high school after moving to California. This storyline does also deal with some heavy material in regards to anti-Semitic bullying, but the way said story plays out is mostly that of a classic "nerds vs. jocks" high school comedy. Sammy has plenty of positive high school experiences as well, and girls start to take an interest in him. The scene where Sammy's first Christian girlfriend tries to inspire him to let Jesus into his heart might be the funniest thing Spielberg's ever directed; at the world premiere, you couldn't even hear some of the dialogue because the audience was laughing too much. Sammy's ultimate victory over his worst bully comes about via a particularly creative and somewhat surprising method that serves as both a thematic cap and winking meta-gag.

Every individual element of "The Fabelmans" is great, from Janusz Kamiński's graceful cinematography to John Williams' final musical score for Spielberg (the composer officially retires from movies after next year's "Indiana Jones 5"). The one thing holding me back from declaring "The Fabelmans" an instant classic is that the many elements of the story don't fully come together. Each strand of the movie (the amateur movie-making, the divorce drama, the high school comedy) is individually very interesting, and there are connections between them, but it's not the most carefully constructed narrative. Spielberg likely figured that the audience for his semi-autobiography would put it all together in the context of his subsequent film career — a safe bet, but I can't imagine the film would hold together strongly without the background knowledge to make it all cohere. You can call it unfocused, but the 2.5-hour runtime of "The Fabelmans" flies by, and the film stays artistically engaging throughout.