How The Disaster Artist Differs From The Book

In 2003, Tommy Wiseau released "The Room," his magnum opus in which he starred, directed, wrote, and produced. While the film was unanimously panned back then, something about the film's unconventional production and the enigmatic artist behind it attracted not only audiences but also celebrities the likes of Paul Rudd, Patton Oswalt, Seth Rogen, and James and Dave Franco — the latter two of whom would eventually bring the story behind "The Room" to the big screen.

The film's appeal grew in the several years since — by 2008, it had achieved its status as a cult classic; in 2013, a book based on the making of the film had become a New York Times bestseller; and finally in 2017, the book was adapted to a major motion picture that with A-list actors playing the roles of people who themselves had struggled to break into Hollywood. While Wiseau and his best friend and "The Room" co-star Greg Sestero (who had written "The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made") may not have made it into Hollywood's big leagues as they had hoped, their story has definitely become a Hollywood phenomenon.

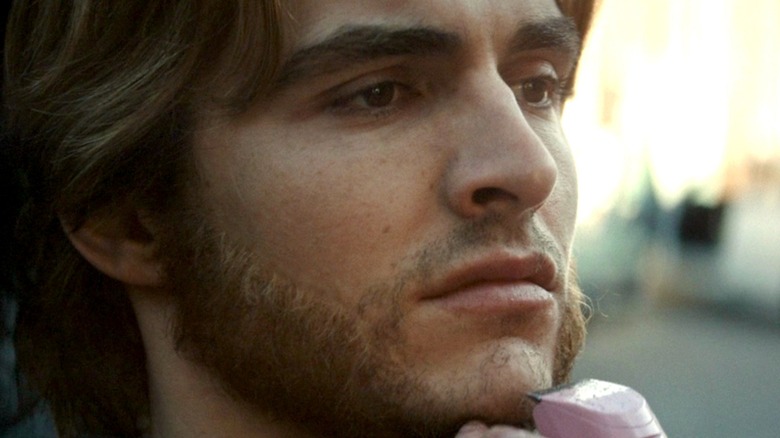

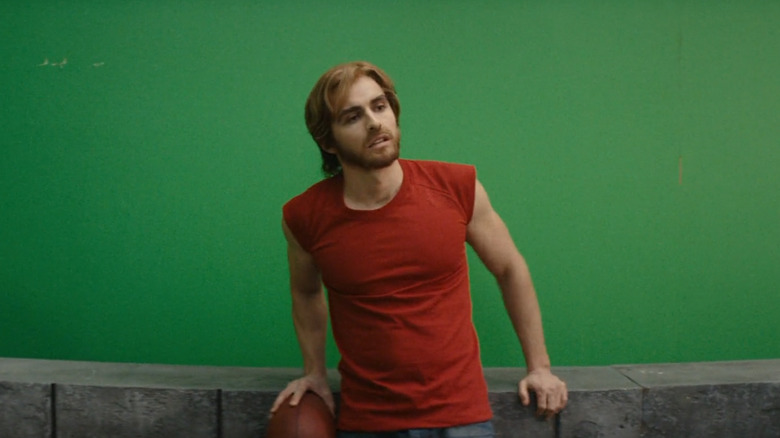

Released in 2017, "The Disaster Artist" follows the friendship of aspiring actors Tommy Wiseau and Greg Sestero and their journey of creating "The Room," which would go on to be widely known as "the worst film ever made." Directed by James Franco, the film stars Franco as Tommy and younger brother Dave playing Greg, along with a supporting cast that includes Alison Brie and Seth Rogen. The film adaptation received acclaim and accolades — earning a nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay at the 90th Academy Awards and winning James Franco a Best Actor prize at the Golden Globes. While it stays true to the book in spirit, there are several darker aspects of the true story and its characters that the film does not explore very deeply.

The opening night response to The Room

In the film, the opening night response to "The Room" becomes disappointing for Tommy, who genuinely believed he had made a true American classic that would be remembered in the same vein as "Citizen Kane" and "Gone with the Wind." Instead, audiences in the theater are flabbergasted by the film, laughing at Tommy's bad acting and other atrocious creative choices he made as a writer and director. It isn't until Greg consoles him that Tommy realizes his film does at least have some effect on the audiences — who are shown to be having a good time as they laugh and cheer at the film — even if it's not the effect he expected. In response to the audience's ovations and name chants, Tommy enters the stage and declares that he had intended the movie to be a comedy, going along with the audience's responses.

Everything that is seen happening in the course of a single night actually took place over the course of years. Later, when two film students saw "The Room" screening on its final day and urged people to see it, the movie began to gain a cult following. Years later, viewers finally learned to appreciate "The Room" for what it is, cheering at the movie's unintentionally amusing scenes, and Wiseau and Sestero began to embrace the movie's cult following. Although their opening night wasn't as cathartic as it was in the movie, Sestero does represent Wiseau's sense of pride and awe at the conclusion of the book.

Greg wasn't the original actor for Mark in The Room

In the film, Greg immediately says yes to playing Mark in Tommy's movie "The Room" after reading the screenplay in a single sitting. In reality, Wiseau had originally cast another actor as Mark, since Sestero had repeatedly turned down the offer to act in the movie after reading the screenplay. Despite having signed a contract and gone through weeks of rehearsals, Wiseau wasn't sure if he wanted to work with the actor, whom Wiseau referred to as "Don" even though his real name was Dan. It wasn't until Wiseau offered a large sum of money and a brand new car to Sestero — who was financially struggling at the time — that Sestero finally relented and accepted the role, even though he had mixed feelings about the movie and guilt about what was going to happen to Dan.

However, instead of directly telling the original actor he was being replaced, Wiseau orchestrated a complicated scheme of going behind his back in "transitioning" the role of Mark back to Sestero. Knowing that the cast and crew would revolt against Wiseau's decision to replace one of his lead actors, Wiseau shot the same scenes he was shooting with Dan, with Sestero, claiming that the film's "producers" (which was himself) wanted him to shoot some scenes with Sestero as Mark. Everyone on the set finally understood what Wiseau was attempting to do, and Dan eventually left the movie, not without having to plead with Wiseau to pay him for the job he had already done. Dan had attended the opening night premiere of "The Room," harboring no grudges against Wiseau and Sestero after watching the finished film.

Tommy's writing process of The Room

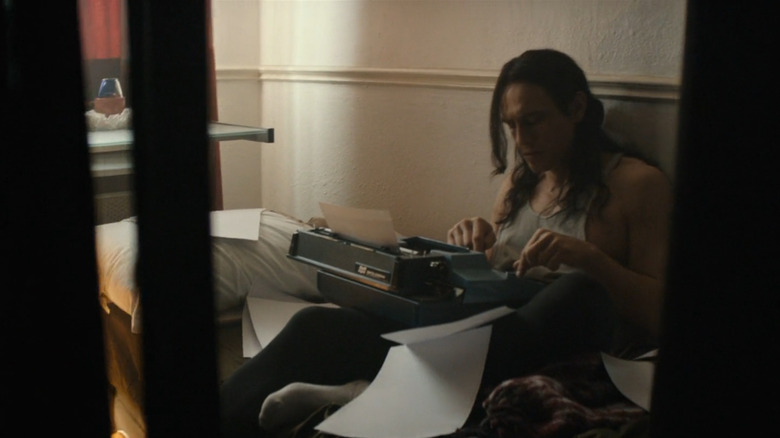

Tommy Wiseau's decision to make his own movie after constant rejections from Hollywood wasn't as epiphanic in reality as it is in the film. It had been a looming idea for Wiseau, who finally decided to start writing his "all-American classic" after being awed by "The Talented Mr. Ripley." The writing process was very frustrating for him, a lot of which he had channeled onto Greg Sestero as a roommate. Both their frustrations had built up to a nasty confrontation in Wiseau's car, when Wiseau impulsively told Sestero that he's kicking him out of the apartment. Wiseau immediately felt regretful about lashing out at Sestero, and he left Los Angeles the next day, claiming to go on a "business trip" to London. He remained absent from Sestero's life over the course of several months, occasionally sending him voice messages claiming that he was in London, even though Sestero had plenty of reasons to believe that he was actually in San Francisco.

Sestero received a lot of distressing calls and messages from Wiseau during this period, including some despairing messages indicating that Wiseau had been going through a difficult time mentally. Though Sestero had gotten worried about Wiseau, he had no idea what he could do since he didn't even know where exactly Wiseau was. Finally, Wiseau showed up after several months, having emerged from his lengthy and mysterious "dark night of the soul" phase, with the completed script of "The Room." While the film does cover Tommy's writing process in a montage that shows his mild irritations trying to crack the story, it comes nowhere close to capturing the true toll that the process had taken on Wiseau and his friendship with Sestero.

Who really directed The Room?

Although "The Room” does seem like something that would be purely Tommy Wiseau's brainchild, the original screenplay he'd written — which started as a stage play, then a novel (per Vox) — made much less sense than the final movie, believe it or not. Sandy Schklair, the film's screenplay supervisor, played by Seth Rogen in "The Disaster Artist," claims in a book to have played a large role in shaping Tommy's movie to have some degree of coherence. While the film adaptation shows Sandy taking on directorial duties such as instructing the actors, calling takes, and attempting to translate Tommy's absurd text to screen, Greg Sestero admits in his book that, "The only reason we'd gotten anything even remotely watchable on film was due to [Sandy's] ability to turn Tommy's vision into something slightly less extraterrestrial." In the years since "The Room" became a peculiar cult classic, Schklair would go on to claim that he was the real uncredited director of the movie, which Sestero remarked to be "a bit like claiming to have been the Hindenburg's principal aeronautics engineer."

While the film adaptation shows Tommy firing Sandy along with the rest of the crew following an ugly argument during the filming of the sex scenes, Sandy actually left the project just a few days before the shooting of the sex scenes, having somewhat anticipated the awkwardness of shooting those scenes with Tommy as well as getting a much better work opportunity. In the end, Sandy is depicted as relishing the horror of the finished film's opening premiere, but in actuality, Schklair — along with a few other cast and crew members — wasn't invited because Wiseau believed they all had "abandoned" him.

Tommy and Greg becoming roommates

The film shows Tommy Wiseau and Greg Sestero moving to Los Angeles to pursue their dream of acting together, forming a supportive and collaborative duo. Tommy allows Greg to live in his LA apartment for free, and the two are never shown to squabble as roommates normally do — until Greg decides to move out to live with his girlfriend Amber (Alison Brie), a disappointment that Tommy tries to deflect and repress. In reality, Sestero was the first one to move to Los Angeles and paid $200 a month to reside in Wiseau's LA apartment while Wiseau remained in San Francisco for a year. After seeing Sestero getting an agent and his first big acting gig, Wiseau started thinking of moving to Los Angeles too, a possibility that worried Sestero, as he knew that Wiseau was starting to feel competitive with him.

As several hurdles came along with Wiseau and Sestero's long-distance friendship, Wiseau gradually increased the rent on his friend and eventually moved into the apartment. Their time together as roommates had been very emotional and mentally taxing for Sestero, who found himself having to bear the brunt of Wiseau's unpredictable behavior, constant irritations over minuscule things, frustrations stemming from his Hollywood rejections, and struggles with writing "The Room." Sestero only stayed in the apartment because the rent was significantly less than anywhere else, still keeping an eye out for any chance he could get to move out, though things got so bad that he started having "the most uncomfortably pleasurable fantasy of wrapping [his] hands around Tommy's neck and squeezing."

Tommy's enigmatic backstory

Though most of the appeal of the secretive Tommy Wiseau lies in his enigmatic presence, Greg Sestero makes an attempt at piecing together a plausible backstory for him from what little he could gather during their decade-long friendship. An entire chapter of the book is devoted to this, painting a rather dark and brutal picture of the hardships Tommy had to endure.

According to the book, Wiseau (called "T—" at this point given the uncertainty of his birth name) was born in Communist Bloc Europe, sometime after the death of Stalin, to a poor family. His hometown was ravaged in World War II, which determined young T— to set his sights on America. Without a formal education, T— learned English from reading whatever English-language books were left in the local library and developed a fascination with films by watching them through a crack in the door of a cinema hall. His love for America would lead to him being alone with no friends and getting bullied and mocked. As a young man, he escaped his communist-controlled hometown and made his way to the French city of Strasbourg, where he had to unclog toilets and wash dishes for a living. He lived in fear of being deported, as well as the terror of never leaving Strasbourg.

Eventually, according to Sestero, Wiseau (now calling himself Pierre) was nabbed by police officers and taken to the Strasbourg police station, where he was stripped, insulted, slapped, and beaten several times before the officers played Russian roulette with him. Broken, he lived on the streets, doing things for money "he will never fully describe or reveal," until he contacted his uncle, who lived in America, to sponsor him. He moved to New Orleans with his uncle but remained unhappy until he was told that California is the place for artists like him — after which he set his sights on San Francisco.

According to Sestero's account, Wiseau felt at home in San Francisco, where he started selling toys and ended up building a very successful multi-property business called Street Fashions, a possible explanation behind Wiseau's mysterious source of wealth, which the film alludes to. However, even Sestero acknowledges that he has no way of verifying Wiseau's backstory and that much of it seems implausible.

Tommy's problematic behavior with women

Tommy Wiseau's demands from the female actors in "The Room" during auditions and shoots were far more disturbing than shown in the film. As Greg Sestero puts it, "I didn't trust Tommy's motives in wanting to see young people — whether in casting or rehearsals or while filming — make out in front of him so frequently." When the women in the auditions would find out that Wiseau himself would be the lead, they'd make some excuse and immediately head for the door. It didn't help that Wiseau had placed a bed in the audition room, and Sestero would have to reassure the women that "The Room" wasn't a porn film. As Sestero says, "Tommy's idea of directing an actress during auditions was to push her in front of a camera and emotionally terrorize her." The few who could withstand Wiseau's attitude fled at the first mention that they'd have to lock lips with him.

When auditioning Juliette Danielle (played by Ari Graynor in the film), according to Sestero, Wiseau made the young actress kiss him for two whole minutes, though actors such behavior is taboo in professional auditions and rehearsals. During the shooting of the love scenes, Wiseau kept the set open for the crew members, though it's customary for productions to keep closed sets for love scenes. This is especially disturbing considering that Danielle was asked to expose her breasts on camera for several days at a time. Sestero confesses in his book that he felt Wiseau prolonged shooting these love scenes, saying, "He delayed things for no reason and stayed naked far longer than was necessary, and he made no secret of the fact that he was enjoying his physical contact with Juliette, who was obviously suffering between takes."

Additional production nightmares during The Room

In focusing on James and Dave Franco's characters, "The Disaster Artist" sidesteps many of the members of production and, in doing so, doesn't completely represent the on-set turmoil Greg Sestero details in his book. Most of the cast and crew were doing double jobs, including Sestero, who was acting in the film and line-producing behind the scenes. Sandy Schklair was the script supervisor on paper, but he says he also fulfilled duties that would normally be assigned to the first assistant director on projects where the director also acts as the lead (per The Hollywood Reporter). This work also, on occasion, according to Schklair, included him stepping into the director's chair, at Wiseau's request.

While Wiseau spent millions on the film, buying expensive cameras and equipment and making a personal bathroom for himself alone, he was surprisingly very stingy when it came to paying his crew and supplying them food, water, and air-conditioning and compensating them for overtime work. Because there was no proper schedule for the crew to decide when to dismantle one set and build another one, the extra cost of materials was often borne by the set decorators since Wiseau refused to pay for it. Both Sestero's "The Disaster Artist" and Franco's film, though, depict the production of "The Room" as an amateurish nightmare, compounded by a director-producer-writer-star's massive ego and questionable, and at times unprofessional and deplorable, behavior behind the scenes.