Whatever Happened To HoneyFund After Shark Tank?

In the nest of gilded machinery that is the wedding industrial complex, it seems there's no shortage of ways to help couples and their guests spend money. Need a cake in the shape of your beloved Goldendoodle? Done. How about a ring cast in individually collected grains of sand from your favorite beach? Also doable. Oh, and if you're intent on having bridal parties, but simply don't have any friends or relatives, you can always hire your own bridesmaids (aka, glorified wedding assistants in a shiny new package). Given the increasing cost of just about everything in recent years, many couples have chosen to forego the malarky of registering for appliances and flatware and get straight to the heart of their actual needs instead, by asking their friends and family to contribute to their wedding or honeymoon financially (via the New York Times).

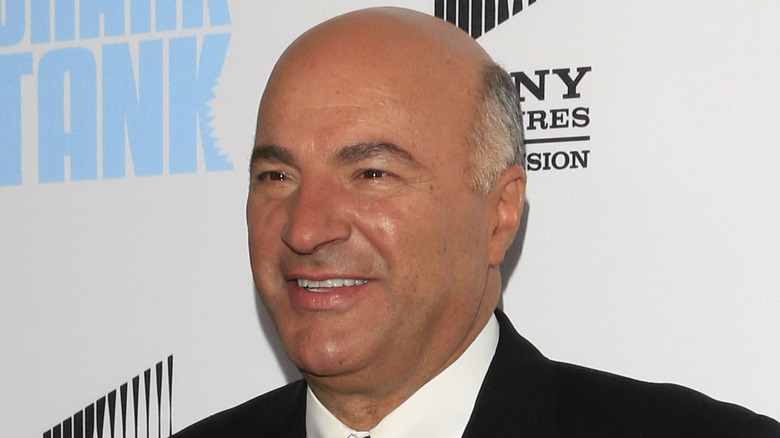

Noting the need for a less awkward way to do this while planning their own wedding, entrepreneurs Josh and Sara Margulis created Honeyfund — a site that allows couples to crowdgift (crowdfund for gifts) for money that can go toward their honeymoon — in 2006. After several years in business and just $217,000 in actual profit, the couple took their company to "Shark Tank" in 2014 (per IMDb) hoping for an investment of $400,000 in exchange for 10% of their company. Three hungry "Shark Tank" stars took the bait, but in the end, the couple said "we do" to Kevin O'Leary, aka Mr. Wonderful, and his unique — but potentially costly — offer.

Kevin O'Leary got creative with his offer

In 2014, Honeyfund had already raised over $200 million in honeymoon funds for their users, earning revenue of close to $1 million. Though couples could sign-up for free, the site offered package upgrades (read: more customization) for a fee, and had a partnership with PayPal that allowed them to take a small percentage of each collected donation. It cost roughly 88 cents for the company to acquire a new customer, we learn during the pitch, and that customer's dollar value for the couple was, on average, around $9.

Kevin O'Leary was skeptical of the company's valuation, which was based on projections for 2015, and would require the company to grow — in a very short period of time — by a whopping 350 percent. In order to ensure he made his money back even if the company failed to take off, O'Leary offered the pair the $400,000 (sans equity), but on the condition that, in return, he received one-third of their transaction revenue until he made his initial investment back three-fold. In other words, as soon as Honeyfund was able to give $1.2m back to O'Leary, he'd swim away and leave them be.

Given the growth variable upon which their happily-ever-after relied, the couple would need Honeyfund's year-old sister site, Plumfund (basically, a less specifically targeted Honeyfund) to start generating many more new customers, as well as a pile of revenue. To paraphrase shark Robert Herjavec, the pair's plan for growing one fund was to attempt to grow...another fund. So, how'd that work out for them?

Mr. Wonderful hooked Honeyfund up

Unsurprisingly, attaching the success of one relatively new company to the success of an even newer secondary company came with some hurdles for the duo. Although a "Shark Tank" Season 7, Episode 3 update (per Shark Tank Blog) revealed Honeyfund had since done over $630,000 in sales (and a representative from the company said its visitors increased by a full three percent since its primetime appearance, per SEOAves), in Season 2 of "Beyond the Tank," we learn that the profits from those sales were being used to (attempt to) make Plumfund profitable. Essentially, the venture the couple had hoped would contribute to their parent site was now taking away from it. Their plan? Make Honeyfund's elite package free for all users, in the hopes that a lower customer acquisition cost and higher traffic on the cross-marketed site would result in a major increase in Plumfund transactions and partners.

If your response is something along the lines of, "wait...what?", then you're in good company. The idea of doing away with the vast majority of the company's major revenue stream had Kevin O'Leary scratching his head (quite literally) as well. He had the couple amend their plan slightly to create a buffer in the event that they had to go back to charging for upgrades, and told them they had just one year left to try and make the Plumfund, which was still struggling in 2016, profitable. He also offered them something only Mr. Wonderful could: a sit down with the editor-in-chief and co-founder of The Huffington Post, Arianna Huffington.

Sara is steering the ship solo

By all accounts, the Huffington Post mogul's quid pro quo with the entrepreneurs — essentially, free advertising in exchange for free content — helped the company burst further onto the scene. As SEOAves reports, the company's valuation went from $4 million at the time of its first "Shark Tank" episode to $20 million at present. In her sit down with O'Leary and Sara, Huffington pointed out that divorce might be every bit as profitable for Plumfund as weddings had been on Honeyfund — a theory borne out by one of the site's popular current uses.

On that note, the company appears to be thriving in the hands of its current and sole CEO Sara, who bought Josh out from the company when the pair divorced in 2019. Speaking to Tech Crunch in 2020, the entrepreneur explained, "the more [Josh and I] pulled apart professionally, the more opportunities I saw to organize the team the way I wanted." The $20 million success story is also getting just as much press as ever. In this year alone, it made The Knot's list of "The 8 Best Honeymoon Fund Registries," and was voted Best Overall (for such registries) by Brides. Sara was also recently interviewed by Medium for a series called "Power Women."

There's a lot one can learn from the story of Honeyfund, including that some risks really do result in reward. But the biggest lesson here might just be that while life's major events, milestones, celebrations, and tragedies aren't always predictable, they are, inevitably, costly.