Underrated Classic Movies You Need To Watch

When you think of classic movies to catch up on, more than a few obvious choices come to mind: "Casablanca," "Citizen Kane," "Gone with the Wind," "The Wizard of Oz," "Singin' in the Rain," "Psycho," "Lawrence of Arabia," "Some Like It Hot." But that barely scratches the surface. Although it's still a very young art form, the motion picture industry has churned out thousands of films from the days of silent cinema to today. With more than a century's worth of options to choose from, it can feel daunting to check off every important classic movie you need to watch. And that doesn't even cover those overlooked gems that are lurking out there waiting to be discovered.

Many of the films on this list were dismissed in their time by critics, audiences, or in some cases, both. Some were big hits that were seemingly lost to time, while others were victims of circumstance upon their release. Whatever the case may be, each has since been reappraised as a classic, and thanks to home video and streaming, these titles are now widely available for new audiences to dig into.

For the purposes of narrowing things down, we decided to focus on films released between the end of the silent era through the beginning of the New Hollywood of the 1970s. Although it would be foolhardy to assemble a definitive list, this is a good starting point for anyone looking for some new recommendations. Here are several underrated classic movies you need to watch.

The Circus (1928)

By the time Charles Chaplin made "The Circus," the writing was on the wall for silent cinema. "The Jazz Singer," the first film to utilize synchronized sound during select sequences (mostly of Al Jolson singing), was all the rage when it hit theaters in 1927, tallying a whopping $3 million at the box office, according to The Numbers. Studios were scrambling to implement the new technology for their upcoming releases, and by the end of the decade, silent movies were all but extinct. Yet Chaplin was able to avoid the talkies for a little while, even managing to produce two more silents during the 1930s ("City Lights" and "Modern Times").

In this 1928 release, Chaplin's Little Tramp stumbles his way into a fledgling circus while fleeing the police, and lands himself a job as a clown. In between high-wire stunts and acrobatics, he falls in love with the beautiful horseback rider (Merna Kennedy), who's also the ringmaster's (Al Ernst Garcia) stepdaughter. But he'll have to compete for her affections with the handsome tightrope walker (Harry Crocker).

Although he won a special prize at the first annual Academy Awards for the film, you don't often hear "The Circus" mentioned amongst Chaplin's best work. Yet it's been rediscovered and reappraised by critics in recent years. Andrew O'Hehir of Salon praised it as one of the director's undiscovered masterpieces, calling it, "a brilliant combination of light and darkness, tenderness and violence, and yes, laughter and tears." Keith Ulrich of Time Out concurred, saying, "it's clear we're watching a performer at the peak of his powers."

The Scarlet Empress (1934)

Fans of Hulu's "The Great" might be interested in checking out this take on the life of Catherine the Great, which is surprisingly modern for a film released in the 1930s. It's perhaps the best collaboration between Austrian-American director Josef von Sternberg and his muse, Marlene Dietrich, who, having scandalized German audiences with "The Blue Angel," was brought to Hollywood by Paramount Pictures. They produced six more films together — including "Morocco," "Shanghai Express," and "Blonde Venus" – that were strikingly stylish, hypersexual, and surrealistic by major studio standards.

Dietrich plays German Princess Sophia Frederica, who is betrothed to the next Emperor of Russia, Grand Duke Peter (Sam Jaffe). Yet upon her arrival in Moscow, she quickly learns that her soon-to-be husband is far from capable of assuming the throne (or producing an heir). She begins an affair with the dashing Count Alexei (John Lodge), and before long is scheming to steal power from her half-witted hubby.

Released right as the Hayes Code began cracking down on what it deemed Hollywood immorality, per MasterClass, "The Scarlet Empress" is shockingly frank in its decadence and depravity, and highly stylized to boot. As Roger Ebert wrote, "Its primary subject is von Sternberg's erotic obsession with Dietrich, whom he objectified in a series of movies ... that made her face one of the immortal icons of the cinema." Dave Kehr of The Chicago Reader said it "turns the legend of Catherine the Great into a study of sexuality sadistically repressed and reborn as politics."

Make Way for Tomorrow (1937)

Leo McCarey expected to nab an Oscar in 1937, but was apparently taken back when he won for his direction of a comedy, "The Awful Truth." "Thanks," McCarey reportedly told the Academy, "but you gave it to me for the wrong picture." That same year, he had helmed the sweetly sentimental "Make Way for Tomorrow," which was virtually ignored when it was released. Yet it has gained appreciation since then, even famously inspiring Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu's 1953 masterpiece "Tokyo Story."

Set during the Great Depression, it stars Victor Moore and Beulah Bondi as Barkley and Lucy Cooper, a retired couple who are about to lose their home to foreclosure. Their adult children can't afford to take them in together, so son George (Thomas Mitchell) and daughter Nellie (Mina Gombell) decide to split them up, each taking one of their parents. Yet even that proves too much of a burden for their busy offspring, and before long Barkley is sent to California, and Lucy is placed in a nursing home on the other side of the country. The two spend one last day together before tearfully departing on a train platform.

As Orson Welles is said to have put it, "it would make a stone cry," and although Great Depression-era audiences stayed away, contemporary critics have certainly shed their share of tears. "The great final arc of 'Make Way for Tomorrow' is beautiful and heartbreaking," raved Roger Ebert, while James Berardinelli of ReelViews wrote, "McCarey pinpoints the self-absorption that results in the neglect of those whose presence demands sacrifice."

The Women (1939)

The year 1939 is often regarded as the best year in movie history, and for good reason: "Gone with the Wind," "The Wizard of Oz," "Stagecoach," "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," and many others were all released during that 12-month period. So fertile was the film soil in 1939 that it even produced a number of titles that were underappreciated at the time but have since been deemed classics. Take, for instance, George Cukor's "The Women," which was completely ignored by the Oscars despite stellar reviews.

Living up to its title, "The Women" doesn't feature a single man in its 130 speaking roles. Yet the story, ironically enough, centers on one very consequential guy. When Mary Haines (Norma Shearer) learns from her friends Sylvia (Rosalind Russell) and Edith (Phyllis Povah) that her husband is having an affair with shopgirl Crystal (Joan Crawford), she travels to Reno for a divorce. Along the way she meets a trio of women all headed to Nevada with the same mission: The Countess de Lave (Mary Boland), sheepish Peggy (Joan Fontaine), and chorus girl Miriam (Paulette Goddard), who's having an affair with Sylvia's husband. But rather than leave her husband, Mary decides to get him back.

Amongst contemporary reviews, Ted Shen of The Chicago Reader raved, "this glossy 1939 satire about pampered Manhattan wives hasn't lost its bitchy edge." Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian wrote, "around this drama of duplicity and infidelity, Cukor creates a brilliant spectacle, halted by Shearer's moments of stunningly serious emotional devastation."

Dance Girl, Dance (1940)

Hollywood's Golden Age was anything but when it came to women behind the camera, who had very few opportunities for employment in the film industry outside of select fields. One woman (the only woman, in fact) who was able to break through and direct during this period was Dorothy Arzner, whose career began in the silent era and ended in the 1940s. Overlooked in her time, Arzner's films are now being rediscovered and reappraised, including this showbiz melodrama featuring an early performance by Lucille Ball.

"Dance Girl, Dance" is the story of two showgirls who start as friends and turn into enemies: Judy (Maureen O'Hara), a sweet-natured aspiring ballerina, and Bubbles (Ball), a conniving bombshell who'll do anything to make it to the top. Judy falls in love with wealthy playboy Jimmy Harris (Louis Hayward), but Bubbles steals him away from her. As Judy's career plummets, Bubbles' star continues to rise, and before long she is left with no choice but to work as her rival's stooge. Yet Judy's pluck pays off in the end, thanks in part to friendly ballet impresario Steve (Ralph Bellamy).

In a contemporary assessment written for The New Yorker, Richard Brody zeroed in on the way Arzner films the dance sequences, which emphasizes the showgirls' objectification in the eyes of men. "The very raison d'etre of these women's performances is to titillate men," he explains, "and that's where the story's two vectors intersect — art versus commerce and love versus lust."

Nightmare Alley (1947)

The release of Guillermo del Toro's 2021 adaptation of "Nightmare Alley" brought renewed attention to this 1947 version, directed by Old Hollywood workhorse Edmund Goulding. While del Toro's take on the William Lindsay Gresham novel is filled with the director's signature vibrant sets and bloody gore, the original is firmly rooted in film noir, cloaking its violent predilections in the shadows. So there's plenty of reason to see this story told a second time.

Tyrone Power, who up to that point was best known as a swashbuckling romantic lead, is terrifying as Stanton Carlisle, a traveling carny who'll do anything to escape the circus. He learns the ropes of mentalism from Mademoiselle Zeena (Joan Blondell), who's in need of a new partner when her alcoholic husband, Pete (Ian Keith), kicks the bucket. Carlisle proves himself an effective "mindreader," and before long is taking his act to the big city as "The Great Stanton." But his ruthless ambition soon gets the best of him.

Although postwar audiences steered clear of this pitch-black morality tale, it's since been reclaimed as a lost classic of the era. Matt Brunson of Film Frenzy called it "one of the bleakest of all '40s flicks, with director Edmund Goulding and scripter Jules Furthman mixing horror, melodrama, and film noir with drunken abandon and pulling it off." Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times wrote, "the hoodwink-picture genre doesn't have a whole lot of peaks to choose from, but 'Nightmare Alley' is one of the few."

The Set-Up (1949)

Two of the most popular genres of the 1940s — boxing movies and film noir, known for dark tones and cynical characters – converge in "The Set-Up," a lean 73-minute drama that was churned out with the sole purpose of playing on the second half of a double bill. Yet it stands as one of the best films ever directed by Robert Wise, who would go on to win Oscars for the mega-budget musicals "West Side Story" and "The Sound of Music."

Based on a narrative poem by Joseph Moncure March, it stars Robert Ryan as Bill "Stoker" Thompson, an aging boxer determined to keep the gloves on a little longer. His wife, Julie (Audrey Totter), worries he'll hurt himself, while his manager, Tiny (George Tobias), has so little faith in his abilities that he's set him up to lose his next match. But Tiny neglects to tell Stoker about this arrangement, and when he wins the fight, he runs afoul of the gangsters who lost their money on his victory.

Seemingly unfolding in real time, "The Set-Up" is all killer and no filler, making it highly re-watchable in an age of endless content options. Among modern assessments, Matt Brunson of Film Frenzy called it, "an intense drama that ends on a note that queasily mixes triumph with tragedy, ultimately allowing a ray of light to pierce the fatalistic darkness." One notable fan is Martin Scorsese, who revealed he used it as inspiration for the fight scenes in "Raging Bull" during a DVD commentary he recorded with Wise.

The River (1951)

When most people think of Jean Renoir (son of the famous painter), they'll usually cite his early French masterpieces "Grand Illusion" and "The Rules of the Game" as his best works. Yet it's his late-career masterpiece "The River" that made Martin Scorsese's list of the 12 greatest films of all time. "I would say this and 'The Red Shoes' are the two most beautiful color films ever made," Scorsese opined in an interview for the movie's Criterion release, and that's no small feat considering this was Renoir's first feature shot in Technicolor.

Shot on location in India, it was also the final film Renoir directed during his brief tenure in Hollywood. It's a coming-of-age story about a young British girl named Harriet (Patricia Walters), whose father (Esmond Knight) owns a jute mill. Both Harriet and her best friend, Valerie (Adrienne Corri), fall in love with the handsome Capt. John (Arthur Shields), whose leg was amputated in the war. But he's captivated by the beautiful, more mature Melanie (Radha Burnier). As tragedy rears its ugly head in her family, Harriet is forced to grow up much quicker than expected.

"The River" has gained critical appreciation in recent years, thanks in large part to a 2004 restoration. Roger Ebert added it to his Great Movies list in 2006, calling it "one of the simplest and most beautiful by Jean Renoir (1894-1979), among the greatest of directors." Wes Anderson also cited it as an influence for his 2007 Indian-set drama "The Darjeeling Limited," per Collider.

The Bigamist (1953)

Ida Lupino was only the second woman in history to join the Directors Guild of America (after Dorothy Arzner), and as such was one of the few women helming feature films during Hollywood's Golden Age. Lupino used her cache as an actress to form The Filmakers Inc., an independent production company that specialized in hot-button message movies. She broke even more ground by directing herself in "The Bigamist," becoming the first woman to pull that double duty.

Written and produced by Lupino's then-husband, Collier Young, it stars Edmond O'Brien as Harry Graham, a San Francisco businessman who's adopting a child with his wife and business partner, Eve (Joan Fontaine). But their family planning is derailed when an adoption investigator, Mr. Jordan (Edmund Gwenn), discovers Harry already has a child in Los Angeles ... as well as a wife named Phyllis (Lupino). Through flashbacks, Harry explains how he met Phyllis during a business trip and, depressed about Eve's infertility, fell in love with her.

"The Bigamist" was praised by critics upon its release, and remains one of Lupino's best-reviewed directorial efforts (along with the pitch-black noir "The Hitch-Hiker"). Howard Thompson of The New York Times spotlighted the star-director's skills behind the camera, saying she "keels the action with such mounting tension, muted compassion and sharklike alacrity for behavioral detail that the average spectator may feel he is eavesdropping on the excellent dialogue." Richard Brody of The New Yorker called it a "glossy yet granular melodrama about the stresses and deceptions of marriage, work, and romance."

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

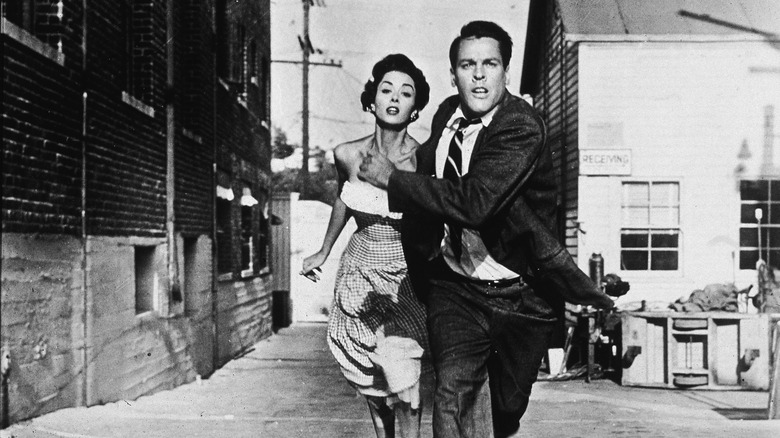

When it was released in 1956, Don Siegel's "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" was largely dismissed as just another cheapie sci-fi flick. Yet contemporary critics have dug deep beneath its B-movie aesthetics to see it for what it actually is: an allegorical rebuke of the anti-communist McCarthyism that was infecting 1950s America. That it also functions as a great low-budget horror film is a testament to its power.

Kevin McCarthy plays Dr. Miles Bennell, a local doctor in small-town California who's perplexed by the number of patients who are complaining that their relatives have been replaced by imposters. But he soon discovers this is more than just mass Capgras delusion: Many of the townspeople have actually been replaced by aliens, born in pods and grown to resemble perfect replicas of their human hosts. It's up to Bennell, his ex-girlfriend, Becky (Dana Wynter), and their friend, Jack (King Donovan), to stop this contagion from spreading across the globe. They'll have to stay up all night to do that, since the aliens take over when you fall asleep.

Much like Philip Kaufman's 1978 remake (which features cameos by Siegel and McCarthy, as well as one of the best horror movie endings of all time), "Body Snatchers" has been hailed by critics as a chilling examination of conformity and groupthink, which was sweeping the nation during the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings. As Tom Huddleston of Time Out put it, "this modest, sci-fi inflected 1956 horror movie might come to be seen as the defining metaphorical work of the twentieth century."

The Long, Hot Summer (1958)

If you've finished binging Ethan Hawke's docuseries "The Last Movie Stars" and are looking to catch up on some Paul Newman/Joanne Woodward movies, this sultry Southern melodrama would be a good place to start. "The Long, Hot Summer" is notable for being the first film the soon-to-be newlyweds made together, and it's an under-appreciated gem for them both.

Directed by Martin Ritt and taking its inspiration from a series of William Faulkner stories, it stars Newman as Ben Quick, a charismatic drifter who returns to his Mississippi hometown. He stirs up some trouble when he meets local businessman Will Varner (Orson Welles), who's looking for someone to take over once he's gone and sees Ben as the perfect choice. He aims to marry the young man off to his daughter, Clare (Woodward), but his ne'er-do-well son, Jody (Anthony Franciosa), and Clare's genteel boyfriend, Alan (Richard Anderson), try to keep them apart.

Although Newman won the best actor prize at Cannes, "The Long, Hot Summer" was largely overlooked in favor of his other 1958 release: the big screen adaptation of Tennessee Williams' "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" (which brought him his first Oscar nomination). Yet time has been kind to this film. It's also tinged with a bit of sentiment, as you can almost see Newman and Woodward falling in love right in front of the cameras.

Fail-Safe (1964)

Although its subject is deadly serious, the timing of Sidney Lumet's "Fail-Safe" was comically tragic. This tense drama about the threat of nuclear annihilation was released the same year as Stanley Kubrick's comedic take on the same subject, "Dr. Strangelove." Though Lumet's film earned rave reviews, it was Kubrick's that was deemed a masterpiece by critics and Oscar voters. Yet over the years, "Fail-Safe" has asserted itself as a classic in its own right.

Much like "Strangelove," "Fail-Safe" imagines what would happen if a nuclear weapon was accidentally deployed at the height of the Cold War. Henry Fonda stars as the U.S. president, who tries to stop a fleet of American pilots from dropping bombs on the Soviet Union when an attack order is mistakenly sent out due to a technical malfunction. He's able to stop all but one of the planes, leading to a devastating decision. Walter Matthau co-stars as Professor Groeteschele, a nuclear expert and rabid anti-communist who sees no problem setting off World War III.

"Fail-Safe" was a box office failure, perhaps hitting too close to home at a time when tensions between the U.S. and the USSR were truly nuclear. Yet it's that frightening realism and cold-eyed detachment that makes it hold up so well today. In a contemporary assessment written for the film's Criterion release, Bilge Ebiri wrote that Lumet, "shows us a system built on the very denial of humanity, one in which individual efforts are completely ineffective and bravery is rendered useless."

Seconds (1966)

Throughout the 1960s, there was a push-and-pull between the dying old Hollywood and the burgeoning new, as the studio system began to crumble beneath the weight of massive box office bombs. American filmmakers were increasingly influenced by foreign directors, adopting many of their stylistic and thematic techniques into their own productions. That's certainly true of John Frankenheimer's "Seconds," a disturbing sci-fi drama that was roundly rejected when it hit theaters in 1966, per The New York Times.

Set in the not-too-distant future, the film centers on Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph), a middle-aged banker who's deeply unsatisfied with life. When he learns of a strange new procedure that allows you to start anew with a different identity, Arthur fakes his death and undergoes reconstructive surgery, emerging looking just like Rock Hudson. Now living in Malibu as an artist named Tony, Arthur is initially excited by the change, but quickly yearns for something different. He asks the doctors to put him under the knife again, which comes with tragic consequences.

Frankenheimer was obviously influenced by the French New Wave, using jagged editing and handheld, black-and-white camerawork (courtesy of Oscar-nominated James Wong Howe). This influence also extends to its sexual frankness and downbeat ending, both of which were out of step with then-current Hollywood filmmaking. Although it flopped with audiences, "Seconds" has gained a newfound critical appreciation. "'Seconds' ends with a kick of paranoia and diabolical goings-on, all driven home to maximum effect by Howe's canted camera angles and fisheye lenses," raved Scott Tobias of The Dissolve in a contemporary review.

The Learning Tree (1969)

Photographer Gordon Parks made history as the first black filmmaker to direct a major studio film with "The Learning Tree," which he also wrote, produced, and composed the score for. Although he's best remembered for his follow-up, the blaxploitation classic "Shaft," his feature debut is a worthy companion piece, showcasing a different side of his directorial talent. And thanks to a new Criterion release, modern audiences can fully appreciate this often under-appreciated gem.

Adapted from Parks' book of the same name, it's set in 1920s Kansas and centers on a family of Exodusters (African Americans who migrated to the state after the Civil War). Young Newt Winger (Kyle Johnson) and his friend, Marcus Savage (Alex Clarke), grow up in the face of racial bigotry, each responding to it in their own ways. While Newt largely ignores prejudice, Marcus fights back. When Marcus is imprisoned for stealing apples, his father, Booker (Richard Wards), murders the white orchid owner as Newt watches from the loft of a barn. As he gains firsthand knowledge of America's racist criminal justice system, Newt falls in love with Arcella (Mira Waters).

The film was praised by the majority of critics at the time of its release. Roger Greenspun of The New York Times wrote, "at its best, 'The Learning Tree' is rich, distanced, cool and sophisticated in its appreciation of formal visual properties." Odie Henderson called it "as beautiful a coming-of-age story as has been told on-screen" in an essay penned for the film's Criterion Blu-ray.

Fat City (1972)

Hollywood's first golden era came to a close in the late 1960s, when the studio system collapsed due to antitrust legislation and a crop of young filmmakers were given the keys to the kingdom, per StudioBinder. Influenced by European auteurs, their films became franker, grittier, and more realistic. Although most directors from the studio system eventually retired, some took the newfound freedom as an excuse to make some of their best work. That's certainly true of John Huston, who had been directing since the 1940s and enjoyed a career renaissance in the '70s, starting with the lean-cut boxing drama "Fat City."

Stacey Keach plays Tully, a down-on-his-luck pugilist who has let himself go from booze. He sees a chance for redemption in the form of up-and-comer Ernie (Jeff Bridges), who he first glimpses sparring at the gym. While Tully tries to get his life back together, even starting a romance with fellow drunk Oma (Oscar-nominated Susan Tyrrell), Ernie neglects his pregnant girlfriend, Faye (Candy Clark). Try as he might, Tully just can't kick the sauce and get back into shape, and he self-destructs as Ernie becomes a bonafide star.

In his four-star review, Roger Ebert praised "Fat City," likening it to Huston's classics "The Maltese Falcon," "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre," and "The African Queen." Huston, he wrote, takes this story of two boxers and "treats it with a level, unsentimental honesty and makes it into one of his best films." It's a sentiment shared by the majority of critics, especially contemporary ones.