That's What's Up: Why The Members Of The Justice League Aren't Really Friends

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."

Q: Are the Justice League members friends or just coworkers? Did they ever go out together to do fun activities like the X-Men or Avengers? — @asimov_fangirl

It's interesting that you bring up the idea of the Justice League as a bunch of people who work together, because I think that might actually be the best description of the way that team works. While other groups of superheroes are built around the idea of being a family, like the Fantastic Four, or have their roots in being a bunch of outcasts who joined up together at school, like the X-Men, the Justice League are kind of the only ones who treat their superheroic exploits as a job. It's not that they're not doing something noble and heroic by fighting against evil, but for the most part, the League has always been made up of characters who have lives that are completely separate from being a team, and that changes the way they relate to each other.

But let's be honest with each other for a second here: what you're really asking is whether anyone actually wants to hang out with Aquaman. And the answer is no.

Nobody wants to hang out with Aquaman

Okay, to be fair, I do know of exactly one (1) comic that involves Batman calling up Aquaman and inviting him over for a bro sesh, but even that is pretty darn spurious. It happened in Gotham Knights #18, and involved Batman's giant penny falling down a hole and Batman needing someone who can breathe under water to help him get it out, which is basically the superhero equivalent of going over to a friend's house because they got a PlayStation after the divorce.

That said, I don't think that the members of the League don't like each other, or that there aren't real friendships between individuals on the team. Despite the fact that they've been punching each other out in comics and movies for the past 30 years or so, Superman and Batman have historically been depicted as pretty close friends, and even went on a double date recently with Lois Lane and Catwoman. There's also an existing relationship between those two and Wonder Woman, who form a pretty close-knit trio of pals who actually do hang out with each other on occasion.

Beyond that, though, it mostly just breaks down into pairs rather than a cohesive group of friends, which is a natural extension of the fact that their friendships are just logical extensions of a superhero team-up story. It's how you get odd couple pairings like Atom and Hawkman or Green Lantern and Green Arrow, or even Flash and Green Lantern—and it's worth noting that while they both hang out with Hal Jordan, the Barry Allen and Oliver Queen of the comics are a lot easier to read as acquaintances than actual friends.

Every now and then, you'll see the entire League do something as a group, but it's almost always along the lines of a Christmas party or a wedding. In other words, it's exactly the sort of thing you'd find among coworkers, not friends. And as weird as it might sound, this has a lot less to do with the characters themselves and their personalities, and a lot more to do with the underlying structure of their entire universe. No, seriously.

Friendships on Infinite Earths

One of the most interesting things about the DC Universe—to me, anyway—is that in the beginning, it was never really meant to be a universe at all. Instead, each piece was built in isolation, meant to stand on its own. It's only as time went on, and the superhero genre began to play with the idea of a shared universe, that major characters started regularly meeting up with each other. Even then, they were first and foremost meant to be solo characters.

That's one of the reasons that each hero in the DCU is concentrated in their own fictional city. Even though the Justice Society of America showed up in 1940 to give some second-tier heroes a boost by throwing them all into one comic, the characters mostly kept to their own little worlds. Those hard lines between characters grew even more defined as the decades rolled on and National, the company that would eventually become the DC Comics we know today, expanded by absorbing characters from other companies. Plastic Man, the Freedom Fighters, and the Blackhawks were acquired from Quality, the Shazam Family from Fawcett, and Blue Beetle, the Question, and others from Charlton. In most cases, these characters ended up being isolated on their own Earths, turning DC's multiverse into a weird, stitched-together collection of fiefdoms rather than a cohesive whole.

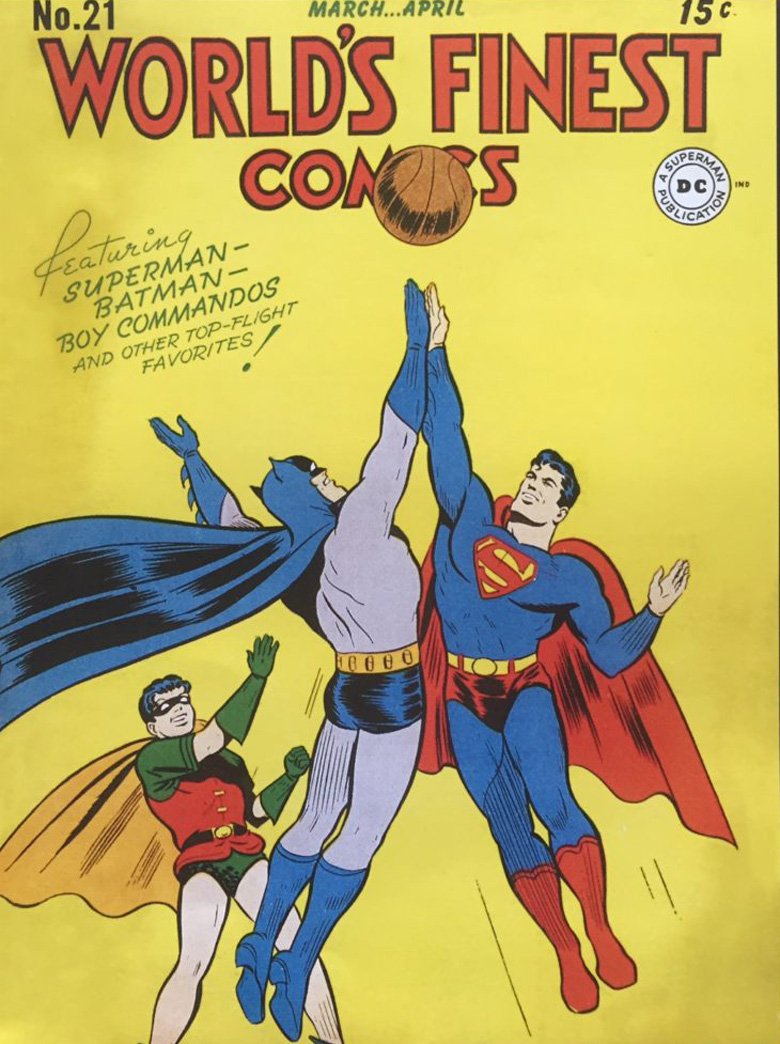

The thing is, it wasn't just the minor characters. Just look at how they treated Superman and Batman in the pages of World's Finest Comics. Since the first issue, the covers featured Superman, Batman, and Robin all hanging out and playing basketball or whatever, but it took years for someone to realize that they should probably appear in the same stories. They only started teaming up in #71, after that series had been around for 14 years.

Meanwhile, in the Marvel Universe...

Compare that with the way things work in the Marvel Universe. Unlike the Distinguished Competition and its isolated creators, many of whom were trying to create the next Superman, the structure of the Marvel Universe was laid down by a relatively small group of people working closely together, and the world they created reflects that. The concentration of superheroes in New York, as opposed to individual cities, mean having them run into each other and team up came a lot more naturally than it does at DC. Batman might need a reason to show up in Metropolis or Gateway City, but Spider-Man doesn't need an excuse to go to Manhattan. He's already there, as evidenced by the fact that Amazing Spider-Man #1 is a crossover with the Fantastic Four.

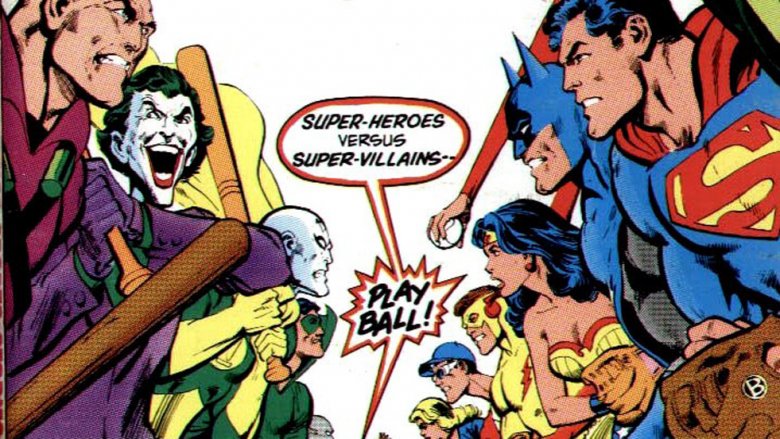

Along the same lines, most of Marvel's big teams—including the Fantastic Four and the X-Men, which also ended up being some of their most prominent franchises—were created as teams rather than being put together from solo characters. Even without the sort of familial bond that keeps the FF together, that changes the dynamic. It creates a roster of characters who feel like they go together in every aspect of their lives, not just the part where they fight villains. In the case of the X-Men, it's even underscored by the idea that they all live together in a big house in Westchester, leading to stories where they'll do stuff like going Christmas shopping together, or the many, many scenes where they'll kick off a new storyline with a baseball game or some hoops.

Even the one big Marvel team that was built for solo characters, the Avengers, doesn't quite have that feeling of being separated in the way the Justice Leaguers do. That, I think, has a lot to do with the way that once you get beyond the big-name core characters, it's always been a showcase book for lower-tier heroes who didn't have their own titles. Characters like Black Widow, Hawkeye, Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch weren't introduced in the pages of Avengers, but they were definitely developed as characters there, and while Captain America is one of Marvel's most reliable solo characters, that's the book where he made his return, too. The result is that he's always going to be associated with the team, and even when he has his own supporting cast and friends outside of it, he fits with the Avengers just as well as with them.

That's not to say one approach is inherently better than the other. As much as I'm a person who's co-written comics where the X-Men play basketball and laser tag, I think the record will show that I'm a pretty big fan of how the DC Universe has come together from all those disparate pieces, too. What's really interesting is how both of those ideas come together—because even when the DC characters are built to be in the Justice League, they still don't seem to get along that well.

Friendship v Drama: Dawn of Justice

In the late '80s, DC threw out the idea of isolating their characters on multiple Earths and rebuilt their universe as a cohesive whole. They'd eventually bring the multiverse and all the alternate reality versions of their characters back, of course—even going as far as adding a dark multiverse for all the bad ideas, which rules—but a lot of the lines dividing the characters were eliminated, or at least blurred a little.

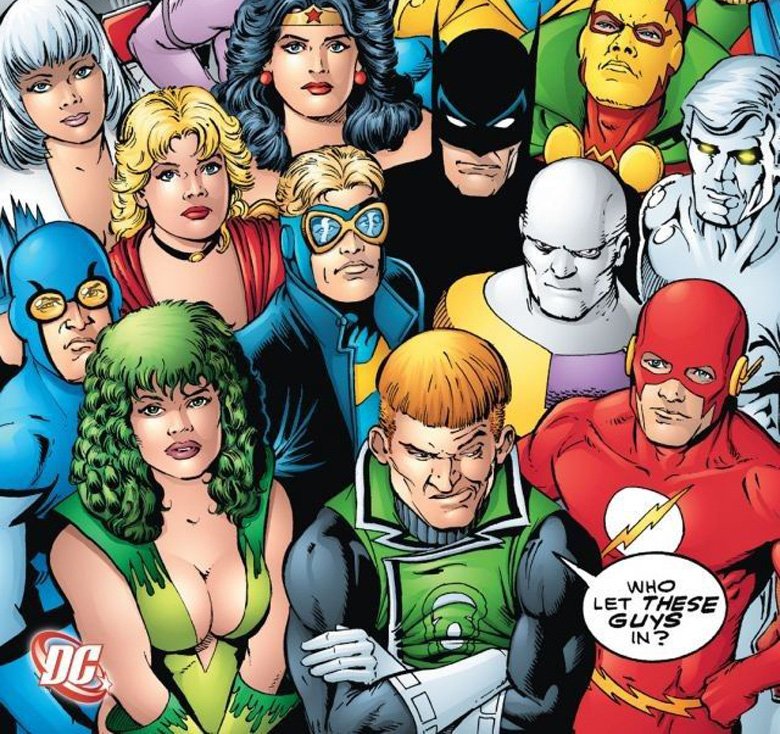

In that era, the bold new idea for the Justice League was that they'd relaunch it without the major characters that readers might expect, allowing characters like Superman, Wonder Woman, the Flash, and Green Lantern to be rebuilt in their own books. It was something DC had tried before a decade earlier with the fairly infamous "Detroit League," but this version had a slightly different approach. For one thing, Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, and Kevin Maguire kept Batman around as the veteran leader instead of Aquaman. For another, rather than creating all new characters, they pulled their cast from a roster of obscure but pre-existing heroes who didn't have anything else to do in this new universe.

Justice League International, as the book would come to be known, was also focused on a different kind of storytelling. Even though it has some great action—including a battle against Despero in issues 38 and 39 that still ranks as one of my favorite Justice League fights of all time—it's usually remembered for its sitcom-style humor. These were third-stringers who were well aware of how they rated, and who had as much downtime where they were hanging out with each other as they did superheroic action.

And they still couldn't get along.

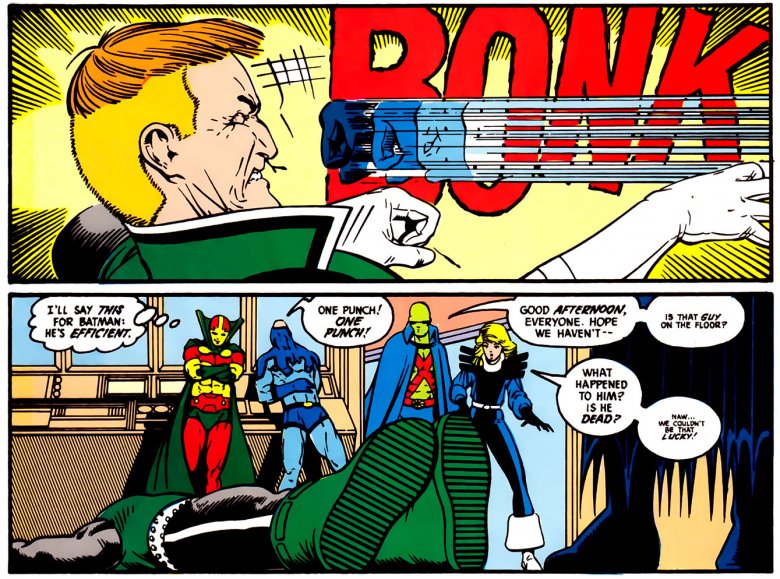

One punch!

In fact, most of the comedy of the book came from all those personal conflicts between the superheroes. The one moment that's more remembered than any other from an entire five-year run that's full of great moments isn't the JLI facing off against the Injustice Gang, or the crossover with the Suicide Squad, or even that big fight when Despero tears through Manhattan. It's Batman punching out Guy Gardner, his teammate, for ... well, for being Guy Gardner, which is honestly a pretty good reason to punch someone.

There were other elements to the cast's relationships, too—a romance or two, the scheming but genuine friendship between Blue Beetle and Booster Gold that pretty much redefined both characters for the next 30 years—but that conflict was the big one. Needless to say, JLI wasn't the first superhero comic to throw that particular brand of fuel into the engine of its plots, with Fantastic Four and the X-Men doing it pretty reliably over the previous three decades, but it might've been the first time it was done that much, with that much of the focus. And the end result was that it was another version of the Justice League that just didn't get along.

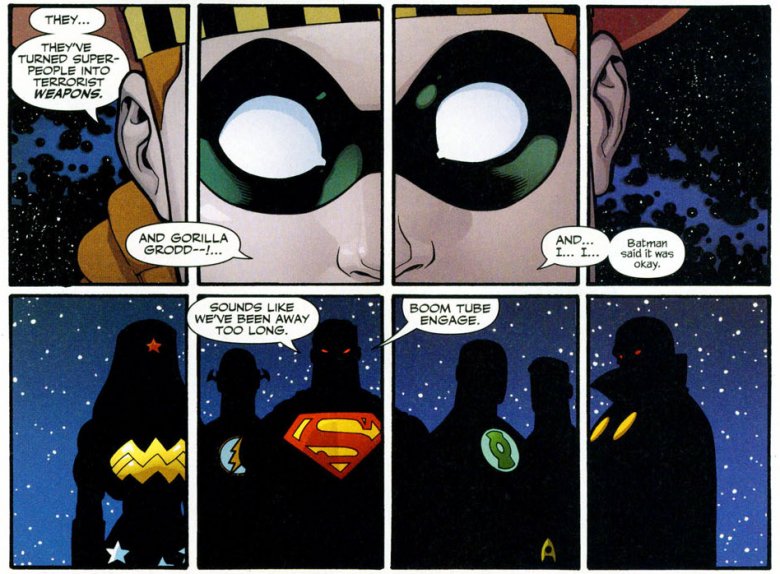

Eventually, the League would be rebooted again, this time bringing in the Big Seven—Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Flash, Martian Manhunter, and Aquaman—to anchor the team. While other lower-tier characters like Plastic Man, Steel, and Big Barda would be rotated through, there was never as much of a focus on interpersonal dynamics in the way there had been.

And that actually made a lot of sense.

We're not here to make friends

The draw of a team made up of solo superheroes, whether it's the Justice League, the Avengers, or even a new incarnation of the X-Men that's made up of all your favorites from previous rosters, is that you get to see all of your favorite characters in the same place. With the Justice League, though, that's a premise that requires a little bit of effort on the part of the creators.

It goes back to that idea of creating superheroes in isolation. If each one is meant to be the protagonist of their particular world, then each hero is, by definition, a character who wins. It's what protagonists do, and without the context of a universe around them, there's no way of really presenting them with a threat that they can't beat. I mentioned Amazing Spider-Man #1 before, and that's a comic that establishes right away that Spidey just isn't on the Fantastic Four's level, which in turn helps to make readers believe that he can be put in danger by threats that the FF would have no trouble dispatching. Even though that's followed by several hundred stories in which Peter Parker triumphs over adversity, that idea remains as part of his character because that potential for failure—and in Spider-Man's case, an actual failure to protect someone he loves from a criminal—is baked in from the start.

But characters like Wonder Woman, Superman, and Batman? They're always taking on all comers and beating them alone. Even the characters just half a step below them are immensely powerful, because they're built to be solo protagonists. Green Lantern has weaponized imagination. The Flash doesn't just run fast, he can do a marathon at the speed of light and jog through time. Martian Manhunter has all of Superman's powers plus he can walk through walls, turn invisible, and read minds. Aquaman, for all my jokes, is the king of 75% of the planet, and can literally hit someone with a whale. If you get him out of the context of always standing next to a guy who shoots lasers out of his eyes and can fly to the moon on his lunchbreak, that's actually pretty impressive.

If there's a threat big enough that those people need to get together to deal with it, then we don't have time for a baseball game, unless that baseball game is going to somehow also defeat supervillains who want to murder everyone. But what are the odds of that?

Ball is life, even for Superman

That's the idea that drives the Justice League, or at least the version of the Justice League that has all those big-name characters on it. If they're fighting something Wonder Woman or Batman could deal with on their own, or even by teaming up together without needing to get Green Lantern involved, then why is everyone there? The very existence of the team is justified by the scale of the threat, and once you get past a certain point, that scale goes well beyond getting together for bowling night.

Again, that doesn't mean they can never hang out, but the fact that they all have their own cities and rogues' galleries to get back to means that the JLA functions a lot more like a job. You show up when you're needed, clock in, beat up Darkseid or Mageddon the Anti-Sun, and then clock out and get back to your life outside of work. Which, in the case of most superheroes, involves fighting people that are slightly less threatening than evil space gods. It's an interesting way of dealing with it—heroism in general is the right thing to do, but helping people on the level of the Justice League is an obligation.

Which makes the characters involved more like coworkers, something that's underscored by one of the most prominent characters on the team being pretty notoriously grumpy about having to interact socially with anyone, ever.

Sometimes I don't get Superman's emails for … years

Friends invite everyone to the party, folks. Coworkers do not.

Each week, comic book writer Chris Sims answers the burning questions you have about the world of comics and pop culture: what's up with that? If you'd like to ask Chris a question, please send it to @theisb on Twitter with the hashtag #WhatsUpChris, or email it to staff@looper.com with the subject line "That's What's Up."