The Untold Truth Of Perfect Blue

Alongside other brilliant anime auteurs like Studio Ghibli's Hayao Miyazaki, Katsuhiro Otomo ("Akira"), and Mamoru Oshii ("Ghost in the Shell") is Satoshi Kon, a filmmaker whose visceral and surrealist movies have left an impact on the cinematic community. Sadly, Kon only had the opportunity to produce four feature films before his death from pancreatic cancer in 2010. He was only 46 (per The New York Times).

Kon was known for blending dreams with reality in his films, focusing more on the rapidly-evolving technological world than the magical adventures in Miyazaki's flicks. In short: where Studio Ghibli films can be seen as a form of relaxing entertainment, Kon's features act like an adrenaline rush. His 1997 debut, "Perfect Blue," truly established these motifs and even went on to inspire some big-name Hollywood directors.

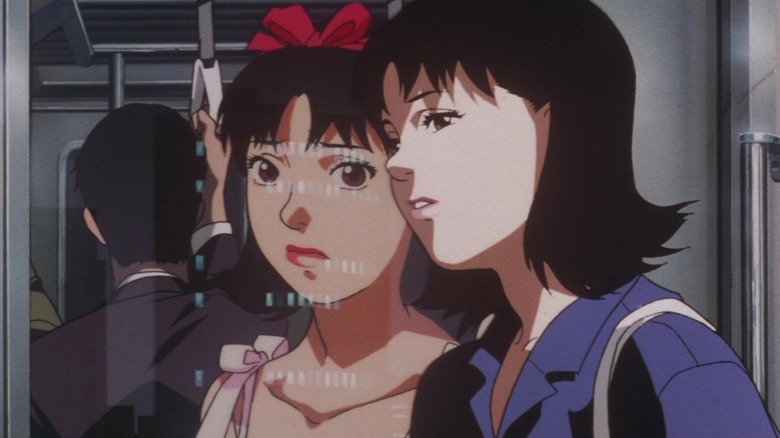

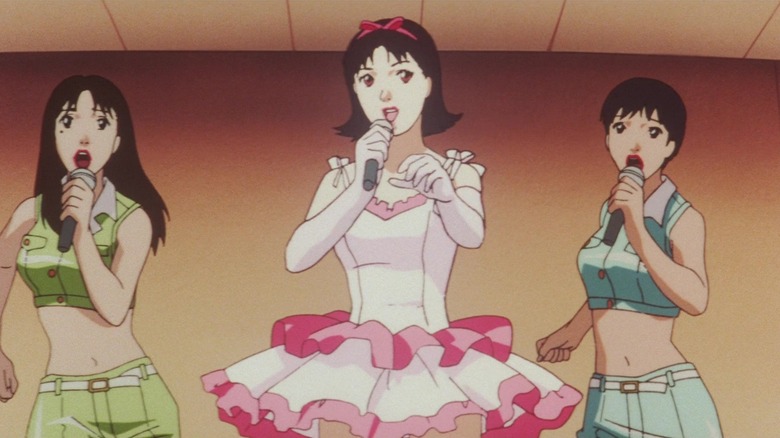

"Perfect Blue" follows Mima Kirigoe, a former J-pop idol who has decided to embark on a new career as an actress. She snags a role on a TV procedural, and simultaneously begins dealing with the stress of an obsessed stalker and voyeuristic fans — not to mention the pressures of the series she's shooting. As Mima spirals into psychosis, she starts doubting her own reality. "If Alfred Hitchcock partnered with Walt Disney, they'd make a picture like this," declared Roger Corman upon viewing Kon's seminal animated classic (via Orlando Sentinel). It's been dubbed one of the most terrifying anime you can watch, so without further ado, let's spiral deep into the world of "Perfect Blue."

Perfect Blue featured elements that became staples in Satoshi Kon's films

As Mima Kirigoe starts her new path as an actress, she's excited to break from her pop idol mold despite an incredible fear of failure. Questioning her career change, Mima's former idol self begins haunting her. As she starts receiving death threats and becomes aware of a blog that tracks everything about her life, Mima's mental health rapidly declines, engulfed in paranoia.

Throughout "Perfect Blue," Mima loses her grip on reality, unable to differentiate between what's real and what's fantasy. It's clearly a theme that director Satoshi Kon was interested in, as his later films feature similar motifs, as in 2006's "Paprika." When speaking to Andrez Bergen in a 2009 interview (via Madman Entertainment), Kon explained, "The interaction of reality and dreams is a motif ... I keep bringing it back into my work." He noted that because of the buzz surrounding that theme in his debut anime, he purposely decided to play with it more.

In a separate chat with The Washington Post, the director explained that his love of dreams comes from his affinity for interpretation; similarly to how each person deciphers their dreams in their own way, that's what Kon wanted his movies to evoke. With the filmmaker citing David Lynch's "Mulholland Drive" as a fantastic example of surrealist cinema, there's no doubt that moments of "Perfect Blue" play out like a Lynchian nightmare.

Perfect Blue turned out exactly how Satoshi Kon imagined it

Before Satoshi Kon flourished as an anime director, he got his start as a manga artist. According to Vulture, Kon's first manga, "Toriko," snowballed into an opportunity with Katsuhiro Otomo (of "Akira" fame), with whom he worked as an assistant.

When asked by Andrez Bergen in a 2009 interview what his favorite part of the filmmaking process was, Kon gushed about the procedure from start to finish, yet specifically cited creating the storyboard as his favorite part (via Madman Entertainment). "When I'm doing this, I really feel like I'm 'making the movie,'" he explained, adding that his background as a manga artist made the process incredibly easy. Kon was, however, quick to note a significant difference between the work of a mangaka and storyboarding: the latter involves dividing the images by 24 frames per second to signify how the characters move in the finalized product.

So, how did "Perfect Blue" measure up to what Kon had in mind at the time of his storyboard? "The final images are what I visualized them to be," he shared in a video interview for the film's home release. "I think in terms of visualized drawings from the beginning." You can see what made his work so special in a fascinating clip from KBN Next Media, which showcases how Kon masterfully choreographed each frame in "Perfect Blue."

Perfect Blue is based on a book of the same name

"Perfect Blue" is actually based on a 1991 novel by Yoshikazu Takeuchi titled "Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis." Interestingly, while some elements remain the same, many aspects of the anime differ from the book (as chronicled by Anime News Network). For instance, the lead character, Mima, isn't part of a J-pop group but is a solo artist, nor does she embark on an acting career. What's more, Satoshi Kon's themes of weaving through fantasy and reality aren't present in the novel, instead focusing on Mima's transformation from a "pure" pop star and dealing with the traumatizing fan reactions when she changes her image.

On his blog, Kon posted a 1998 interview he gave after the film's release, revealing that he didn't actually read Takeuchi's novel when he was approached about making the anime. Instead, he was given a summary of the plot, which he didn't really like. After speaking with Takeuchi and the producer, they allowed him to change elements of the story — with a few requirements. These included having Mima as the protagonist and adding in the character of Mamoru Uchida (or Me-Mania), her obsessed stalker.

As for the significance of the title, "Perfect Blue," Kon never had an answer to share with the press. As he told Andrew Osmond after the movie came out, he merely stuck with the title used for the novel (via All the Anime). "I presume the words had some significance, but as I changed the story and probably the subject as well, I guess the meaning was lost," he shared.

The crew of Perfect Blue was shocked at the final product

"Perfect Blue" went through many transformations to get to the legendary piece of work it's regarded as today. According to an interview Satoshi Kon gave with a German publication at the time of the film's release (via Kon's Tone), he explained, "The original novel was more straightforward action/psycho-horror content than the finished film, but such works have already been taken up in various genres." The director further explains that, at the time, the Japanese animation industry focused on three characteristics: "robots, beautiful girls, and science fiction." Of course, "Perfect Blue," with its surrealist imagery and plot, was much more robust than that.

But swapping the plot into a much more convoluted narrative wasn't the only change to the anime. Per The Guardian, "Perfect Blue" was reportedly set first to be a live-action feature film, yet due to lack of funding, was changed form twice: first as a direct-to-video release, and then to a direct-to-video animation — probably with an aim to focus on the aforementioned attributes found in television anime.

As it turned out, Kon's staff on the project were not horror fans at all and were floored by what they saw in the final product. Speaking with Anime News Network, the director shared, "When the film was finished and we had the first staff screening, one of the main staff said to me, 'I didn't realize it was this kind of film!'" As for Kon, he was completely unfazed during the making of "Perfect Blue," unaware that it would be so revolutionary.

Did Darren Aronofsky purchase the rights to make a live-action Perfect Blue?

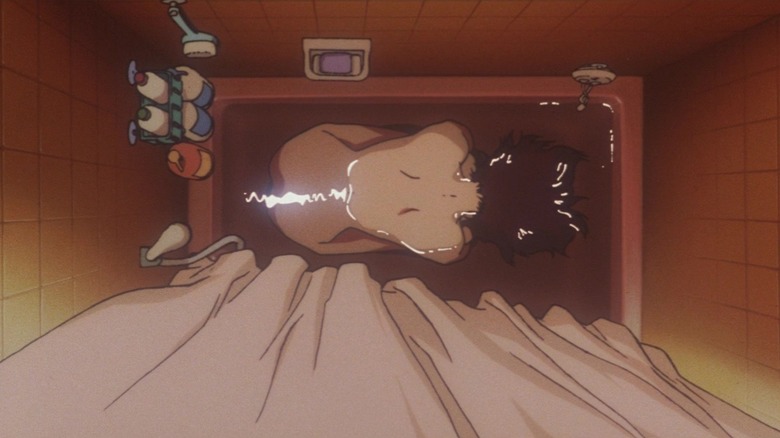

Ever since Darren Aronofsky released his second feature film, 2000's "Requiem for a Dream," a rumor has circulated online that he purchased the rights to a live-action version of "Perfect Blue" (per All the Anime). Perhaps the persistence of this gossip has to do with one particular scene in "Requiem" when Marion Silver (Jennifer Connelly) lies curled up in a bathtub, facedown, and screams into the water. This moment probably seems familiar to those who have seen both films — because it was copied shot for shot from "Perfect Blue."

Satoshi Kon shot down the rumor back in 2001 when he sat down for a joint interview with Aronofsky, while the latter was promoting "Requiem for a Dream." Kon recalled the interview on his blog, Kon's Tone, where he revealed that while Aronofsky did indeed attempt to buy the rights, the contract never went through. As such, he settled for filming the bathtub scene in his psychological thriller, dubbing it an "homage," which Kon found quite humorous.

During a lecture series that Kon later gave (excerpted by Animation Obsessive on Twitter), he elaborated on his thoughts a bit more, with a chuckle. "Overlaps or a ripoff? ... When I asked him, he said it's all an homage." Aronofsky later released 2010's "Black Swan," which, as Dazed describes, includes even more plot similarities to Kon's debut anime. When asked at The Philadelphia Film Festival whether or not he was inspired by "Perfect Blue," Aronofsky denied the notion. "There are similarities between the films, but it wasn't influenced by it" (via Filmadelphia).

Perfect Blue is, at its core, a brilliant commentary on identity

Fans of "Perfect Blue" have tried to analyze the psychological thriller for decades now — just see how complex a Reddit discussion thread can get. With director Satoshi Kon going on record to say that he enjoys making relatively incomprehensible films (via The Washington Post), it raises the question: What is the core theme of "Perfect Blue"? Simply put, the anime is an incredibly well thought-out commentary on identity, particularly the sense of self that is lost within celebrities (or anybody in the public space) when they reach that coveted A-list success.

As Far Out summarizes, the focus hones in on Japan's obsession with pop idols and, specifically, the cookie-cutter images these stars are forced to portray to the public. Indeed, as The Artifice explains, these pop idols in Japan, or "aidoru," are different from your regular singers, as they're essentially created by recruitment agencies that focus more on image than the music itself. The early 1970s are considered the start of this phenomenon, yet the following decade was considered the "Golden Age of Idols," with the '90s only adding fuel to this growing obsession. Considering "Perfect Blue" was released in 1997, it was the perfect commentary for this incredibly relevant sensation.

When Andrew Osmond interviewed Kon at the time of the anime's release (via All the Anime), he asked the director if this conflict of identity is present within all stars. According to Kon, he believes this issue is evident within everybody — famous or not. "'Perfect Blue' is about the tragedy caused by that [conflict] becoming too large," he explained.

The most harrowing scene in Perfect Blue was actually quite significant

In "Perfect Blue," heroine Mima Kirigoe is determined to prove herself as more than a former J-pop idol — she wants to be taken seriously as an actress. Taking on a minor role on a TV procedural, Mima is told that her big break will come if she agrees to partake in a rape scene for the series, which she agrees to do, much to the shock of her manager, Rumi.

The moment makes for incredibly uncomfortable viewing, and though it is, of course, simulated, Mima's horror appears real. While chatting to an American publication after the release of "Perfect Blue" (via Kon's Tone), director Satoshi Kon explained the significance of the cruel scene: it's supposed to signify "the death of an idol." As Kon further divulged, "In English, it might be 'the death of a pop star,' but that doesn't convey the nuance. It is the destruction of the iconography that is literally included in the word 'idol.'"

In a lecture series Kon gave on "Perfect Blue," he explained that during Mima's traumatic experience, her old "idol" self dies, pointing out that even her on-screen outfit resembles what she wore during her concerts. Further, right after the scene, viewers see Mima dressed in all black, seated in such a way that it appears she's mourning — specifically, the death of her old self. Of course, the result of this event leads to Mima's full-blown psychological breakdown.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Perfect Blue is supposed to be a confusing watch

"Perfect Blue" is, without a doubt, a perplexing film to follow. As Mima Kirigoe slowly spirals into psychosis, unable to differentiate whether the hallucinations of her pop idol self are real or not, the audience experiences the same thing. A repeated line in the anime is "Who are you?" — almost as if to remind the viewer to keep guessing through the disorienting frenzy on screen.

In "Cinema Anime: Critical Engagements with Japanese Animation," Susan Napier points out that Satoshi Kon makes it clear within the film's first shot that you cannot trust your perceptions of what you see play out. Kon uses this trick repeatedly throughout "Perfect Blue," showing a scene that appears "real," only to reveal later that it was actually a scene within a scene — such as the events that play out on Mima's TV show. "It's the difficulty of figuring it out that is at the core of the film," the director explained in an interview with Andrew Osmond (via All the Anime), noting that even upon repeated viewings, things are never as they seem. "As you accept that it's meant to be inexplicable, that's fine," he declared.

In a separate interview, Kon revealed that while developing the script, he originally intended to make "Perfect Blue" easier to follow, ultimately deciding on a more imaginative take. While he personally believed that the final product wasn't even that confusing, he also revealed, "We really didn't go out of our way to confuse the viewer." On behalf of all "Perfect Blue" viewers, we thank Kon for taking the more, ahem, "accessible" approach.

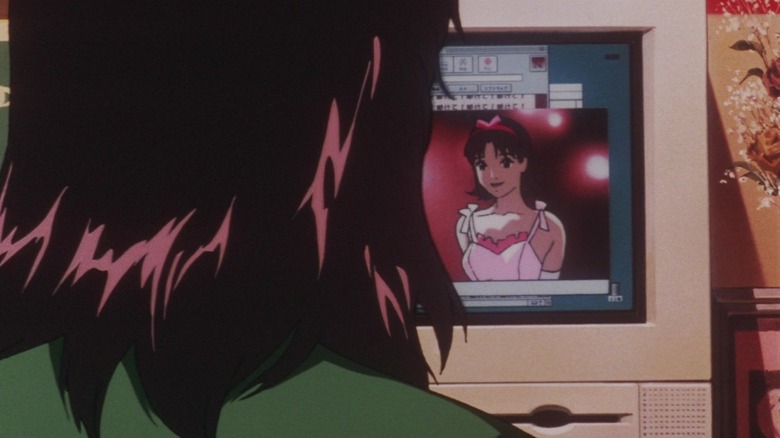

Perfect Blue was eerily prophetic about the digital age

"Perfect Blue" was released in 1997 — a mere four years after the World Wide Web launched in the public domain (per History). Unlike today, when celebrities are scrutinized online for virtually everything they do (and before cyberbullying became the norm), Satoshi Kon cleverly incorporated these themes into his debut anime. Mima Kirigoe is terrified to discover a blog about her life, "Mima's Room," and she grows increasingly paranoid at how the website's author knows everything she does.

It's fascinating to observe Mima's surroundings in the room she lives in, as well. As Kon revealed in a 1998 interview (via Douban), even her physical space mimics the internet and the lack of privacy that engulfs her life. "There are three 'screens' in the room where Mima lives: a TV, a PC and a tropical fish tank with the same 3-by-4 dimensions as a monitor," the director noted. "We also shot Mima's room as if it was being viewed on a TV screen." Curiously, this could lead to theories that Kon predicted invasive reality TV programs that sprung up later on, such as "Big Brother," which voyeuristically records contestants around the clock.

Kon's final movie, 2006's "Paprika," further explores the concept of dreams and compares them to the internet, where the eponymous lead even asks, "Don't you think dreams and the Internet are similar? They are both places where the unconscious mind vents" (via "Asian Popular Culture: New, Hybrid, and Alternate Media").

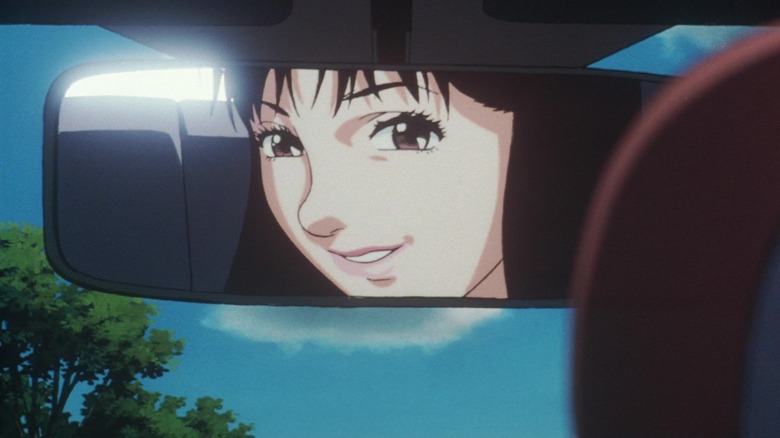

The difference between the final line in the English dub and the Japanese original

There's a peculiar difference between the original Japanese dialogue and the English dub of "Perfect Blue," found in the anime's final line. We discover that, along with Mima Kirigoe's actual hallucinations, her manager Rumi (who suffers from dissociative identity disorder) was also impersonating Mima's "idol" self. After this twist, Mima visits Rumi in a psychiatric hospital.

Upon leaving the building, Mima gets into her car and looks at herself in the rearview mirror. Per Anime Feminist, in the English dub, Mima's voice actress, Ruby Marlowe, declares, "I'm the real thing!" Yet in the original version, a different line is delivered by actress Rica Matsumoto, saying, "No, I'm the real me!" Of course, this leaves audiences to speculate whether or not the epilogue is simply Rumi hallucinating yet again.

We'd be remiss to ignore that at the movie's beginning, Matsumoto provides Mima's singing voice during her first performance. Still, the ending definitely adds some intrigue to Mima's (and Rumi's) fate. Kon never gave any direct insight into the delivery of the final line, but he did offer a tease in a lecture series included as a special feature on the "Perfect Blue" home video release. "I don't mind if there are multiple interpretations," he said, adding, "I personally doubt her [final] words, that she's 'the real me.'"

Was Perfect Blue initially a flop?

On a global scale, "Perfect Blue" has been praised by critics and film enthusiasts. But at the time of its domestic release, Japanese critics didn't know what to make of it. "'Perfect Blue' didn't really receive the recognition of the industry," recalled the anime's producer, Masao Maruyama (per Animation Obsessive), adding, "It was pretty humiliating." Decades later, Maruyama sat down for an interview with Dazed, where he admitted that, due in part to the evolution of the anime field, people had finally begun to see it as a brilliant piece of art.

So, why was "Perfect Blue" such a domestic flop? As Satoshi Kon explained in a 1998 interview (via Kon's Tone), at the time, Japan put a focus on television as opposed to its film industry, so animated feature films didn't have the sort of budget that Disney had in America. What's more, the themes found in "Perfect Blue" weren't exactly in line with the standard tropes found in '90s anime, so some viewers simply didn't understand it–– nor did they try to. Kon was unbothered by those who didn't appreciate his flick, and as he told Andrew Osmond (via All The Anime), "I didn't mean to appeal [to] any particular kind of viewer. I always create what I want to see."

Years later, with "Perfect Blue" finally getting the respect it deserves, fans might wonder — will there ever be a sequel? "I couldn't do it without [Kon]," Maruyama told Interview magazine in 2017, seven years after Kon's untimely death.