The Untold Truth Of My Neighbor Totoro

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

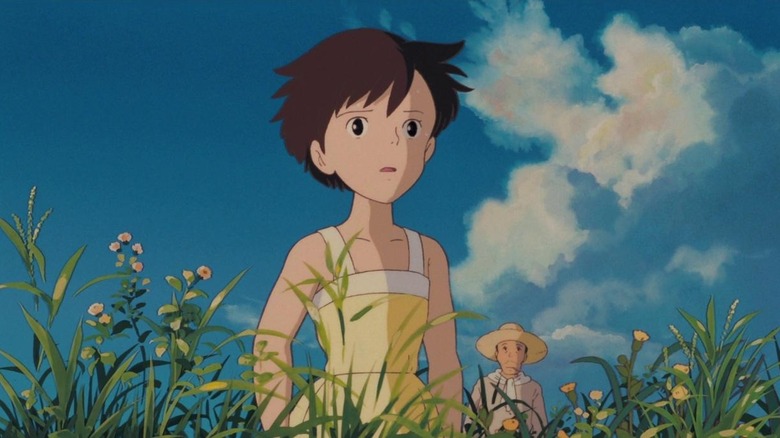

There aren't many movies like "My Neighbor Totoro." Where most family movies would zig, director Hayao Miyazaki zags. Where most of them try desperately to keep the attention of young viewers by constantly throwing something new at the screen, "Totoro" takes its time and finds magic in simple things like clouds creeping across the sky and rain leaving ripples of light in dark puddles. Where most of them pit children against adults, "Totoro" gives its heroes Mei and Satsuki loving parents who encourage their imaginations.

Rather than following Screenwriting 101, and the concept that conflict equals drama, "Totoro" is content to simply show children exploring the world around them and interacting with magical creatures. When dramatic conflict finally disrupts the peaceful atmosphere in the final act, it's all the more heartbreaking for it, and the happy ending is all the more cathartic.

Such an unusual film has got to have some unusual stories behind it, and "My Neighbor Totoro" does. Here are a few of the more intriguing secrets from Totoro's world.

The studio juggled Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies

Studio Ghibli famously released "My Neighbor Totoro" as a double-bill with director Isao Takahata's intense war story "Grave of the Fireflies," about two children evacuated to the country during the firebombing of Kobe. It's an odd juxtaposition, but it makes a certain amount of sense — what could be a better way to decompress after all that pain and suffering than with the warm hug that is "Totoro?"

Theater owners learned the hard way not to screen the films in opposite order; Den of Geek reports theaters that showed "Totoro" had mass walkouts from audiences who didn't want to kill the good vibes of "Totoro" by following it up with "Grave of the Fireflies."

There was another, more practical reason for the pairing: Dani Cavallaro writes in "The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki" that Studio Ghibli realized that their previous one-film-a-year schedule could be disastrous if even one of their movies flopped. But keeping multiple irons in the fire caused its own set of problems. Cavallaro quotes producer Toshio Suzuki, who calls the process "sheer chaos." Animators would have to switch between projects in the middle of production. "Totoro" is already a miraculous movie — that Miyazaki was able to make anything even halfway decent under such circumstances only makes it more so.

Backers thought Totoro was a risky investment

Perhaps the best argument for Ghibli's decision to pair "Totoro" and "Grave of the Fireflies" is that it saved "Totoro" from production limbo. In "Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata," Colin Odell and Michelle LeBlanc recount the struggles Ghibli, still a small startup dependent on outside investors, faced in getting "Totoro" made.

Miyazaki's kid-friendly film was considered the riskier of the two, dismissed because it was "too childish" and "lacked real conflict or action." Meanwhile, according to Den of Geek, the apparent harder-sell "Grave of the Fireflies" attracted investors based on the popularity of Akiyuki Nosaka's original book and hopes that its historical value would attract schools to the box office. The package deal turned out to be the perfect solution: The backers' interest in "Grave of the Fireflies" paid the way for "Totoro," and if one of the two films succeeded, they'd still get a return on their investment.

Of course, the investors were proven drastically wrong. Both films were hits, but "Totoro" grew over time to become an institution. Merchandising alone became massive in its aftermath across Japan and abroad, and Totoro's face even became the official mascot of Studio Ghibli.

Totoro is based on a true story

It may seem like a strange thing to say about a movie with living dust bunnies, a giant spinning top, and a bus-shaped cat, but Miyazaki looked to his own life for the "Totoro" storyline.

There's enough information in Susan Jolliffe Napier's 2018 biography "Miyazakiworld: A Life in Art" to make the connections. Like Mei and Satsuki, he had to live with the uncertainty of his mother's fight with tuberculosis. Miyazaki based the setting on his childhood home in the Kanto district, which led to some friction with art director Kazuo Oga, who remembers in "The Art of 'My Neighbor Totoro'" that his paintings often came out a different color than Miyazaki had in his mind.

Miyazaki is even quoted in the book as admitting the film was largely biographical. One argument with a colleague had them insisting that such a "good kid" as Satsuki couldn't exist. Miyazaki replied: "She did exist! She was me!'"

The animators loved Totoro because they were tired of action scenes

The placid story of "My Neighbor Totoro" might not seem like an exciting prospect to animate, but the crew at Ghibli felt just the opposite.

This was a major reason Miyazaki launched the project: In a magazine article reprinted in "The Art of My Neighbor Totoro,'" he says that after spending most of his early career on action-packed movies like "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind," "Castle in the Sky," and the Lupin III spinoff "The Castle of Cagliostro," he was ready for a change of pace.

"Rather than film action scenes with laser beam attacks," he is quoted as saying, "I yearned to work on an animation with girls playing in fields."

He wasn't alone. Plenty of other animators jumped at the chance to bring "Totoro" to life because "they were a little tired of doing action scenes." That attitude may explain how "Totoro" became such a classic — it's the rare film where the animators are able to make mundane scenes like water running in a stream or wind blowing through the grass as gripping as any space battle.

The house is all the crew member's dream homes

"Totoro" dazzles viewers with all kinds of gorgeously, magically realized locations. But few have made such an impact as the country house, which has inspired many fans to fantasize about living there. That was no accident.

Miyazaki's design team put much thought into the house, determined to make it as enticing as possible. Miyazaki explains the process in "The Art of 'My Neighbor Totoro'."

"We first imagined what an ideal house would look like," he explains. "The staff came up with the idea, and then everyone looked at the rushes. Instead of being impressed by Satsuki and Mei's movements, they all said, 'I want to live there.'"

The end result was a tantalizing country home, filled with eccentric touches and endearing character. In the end, the house is as much a character as any living, breathing thing in the film.

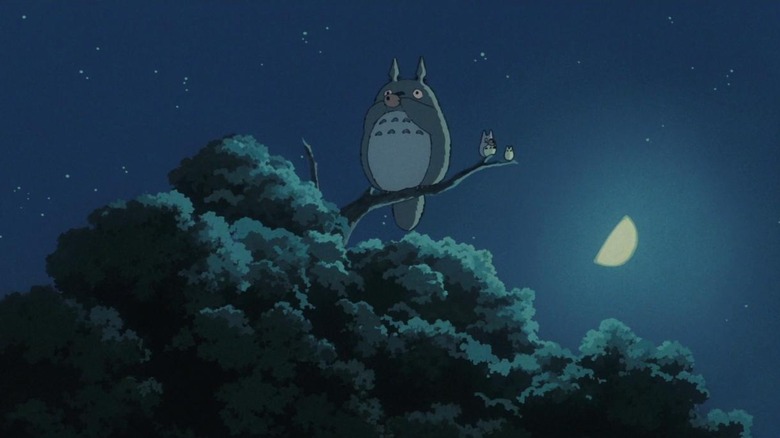

The different Totoros each have names

While the bear-sized main Totoro has become the movie's breakout star, the film also introduces two smaller specimens who lead Mei to their big brother: the transparent white Little Totoro and the blue Medium Totoro.

While those utilitarian titles served Ghibli for most of the production, these characters were originally intended to have more individualized names. A size chart from early in the process shows the three of them, along with other characters who haven't quite coalesced into their more familiar forms, including a soot sprite with legs.

But the most interesting details are in the labels giving the characters' names and ages. The littlest Totoro is also the youngest at 109 and is named Mimin. The medium-sized Totoro is jet-black instead of blue and white, and receives the name Zuku and the age 679. The big Totoro combines both names into Miminzuku, and is 1302 years old.

The Catbus has changed with the times

If any character from "Totoro" is as beloved as the star, it's the magical Catbus, who Mei and Satsuki meet at their father's bus stop and later plays the calvary coming to the rescue when Mei gets lost. This character seems to have fascinated Miyazaki as much as his fans.

The filmmaker invented a backstory for the Catbus that is included in "The Art of 'My Neighbor Totoro'" and reads thusly: "The Cat Bus once assumed the shape of a rickshaw carrier, but the sight of a bus rumbling by excited it so much it turned itself into one."

Sadly, none of this made it into the film, but it does fit well into the screen story, confirming that these magical creatures have been around much longer than the mortals they interact with, while also building on the script's exploration of the changing face of postwar Japan. Miyazaki's other comments go a long way to explaining the Catbus's Cheshire-Cat grin (on top of the obvious "Alice in Wonderland" reference — he even disappears in pieces, leaving "a grin without a cat.") ""The Cat Bus is always grinning. As long as it's running, it's happy."

Storyboards reveal Totoro's lost dialogue

Totoro joins Pluto, Dopey, and Wile E. Coyote, among others, in the long tradition of silent cartoon stars. But that wasn't always the plan.

A site called Soranews24 has translated select pages of a Japan-exclusive collection of original "Totoro" storyboards, including several lines of dialogue for Totoro. While it would be natural to assume that dialogue would remove Totoro's animal-like innocence, the lines cut from his introductory scene actually emphasize that side of his character.

When Mei asks if he's a giant dust bunny, he only responds, "I'm sleepy," and when she asks if his name is Totoro, he just says, "I don't know." Another storyboard from the bus stop scene confirms Totoro still isn't totally clear on the name concept, when he says, "What's that? What's Totoro?" Totoro's last bit of dialogue confirms it's probably for the best that Miyazaki decided to cut all of Totoro's lines, since it introduces an uncomfortable romantic subtext in his relationship with Satsuki.

When she comes to him for help, he says "Kawaii"(cute). Thankfully, the final scene no longer opens the can of worms of an ancient forest spirit flirting with a little girl, instead implying things more subtly via Totoro's blush.

The story originally ended with Totoros in the city

Once Satsuki and the Catbus find Mei, everything ends happily, with the Catbus dropping off the girls at the hospital to see their mother, on the mend. After that, the film delivers an epilogue in still images over the credits, showing the girls' mother coming home and Mei starting school. But "The Art of 'My Neighbor Totoro'" includes an alternate ending that would have taken the Totoros far from home.

Miyazaki describes his early vision to bookend "My Neighbor Totoro" with a journey through the history of industrialization, first backwards and then forwards. As the girls drive to the country house, "the landscape would suddenly change. ... The residential area gave way to paddy fields, and sidewalks turned into waterways. ... The story would begin with the three-wheeler rumbling over there and end with the girls returning to their world" in a modern city.

Miyazaki goes on to describe how this version of the story ends, with "the granny" (possibly either the one Mei and Satsuki met in the country, or one of the sisters themselves many years later) telling the story to children who ask, "Do the Totoros still exist, Granny?"

The film would then show the viewer that they do, even in the city, still playing their ocarinas even if the sound of traffic drowns them out. This scene may not have made it to the screen, but Isao Takahata would pick up on the idea of woodland spirits adapting to city life in his 1994 movie "Pom Poko."

Miyazaki wasn't happy to learn how much a little fan loved Totoro

Hayao Miyazaki makes such sweet, kindhearted films that fans have long been intrigued by the perception that in real life, he's something of a grouch.

When author Tove Jansson complained Miyazaki's adaption of her "Totoro"-like "Moomintroll" books had too much violence and modern elements, he responded by giving the hero a tank. "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness" shows him walking out of his own son's movie debut for a cigarette break after an hour, saying "It feels like I was sitting there for about three hours." When he finally finished it, he said, "I saw my own child. He hasn't become an adult. That's all."

With that in mind, perhaps his response to a fan letter isn't totally shocking. Dani Cavallaro, author of "The Anime Art of Hayao Miyazaki," recalls the time a friend of the filmmaker sent a photo of his daughter kissing the TV while "Totoro" was playing, along with a letter saying she'd seen the movie "over fifty times."

Miyazaki didn't take the compliment well. He wrote back, "Once a year, maybe once in a lifetime, is really how often you should see any of my films. ... Owning a little puppy will teach you a lot more about life than watching 'Totoro' 100 times."

Totoro first came to the US through the least kid-friendly studio around

"My Neighbor Totoro" came out at the height of Japan's Golden Age of Anime, but it would take awhile for Americans to get the memo. Long before every Comic Con was crowded with Gokus and Jojos, it was common for Japanese media to take years to cross the Pacific, often in butchered form. Before it became big business, anime had to get creative for overseas distribution.

"Totoro" finally reached American theaters in 1993, five years after its initial release. With Miyazaki and Ghibli unknown in America at the time, some critics focused on the film's connection to distributor Troma, presenting "Totoro" as another niche film, albeit for a slightly classier clientele than, say, "Zombie Island Massacre."

"Displaying no more than adequate television technical craft, the simple family saga poses no threat to the commercial dominance of Disney cartoonists," read one dismissive review. "U.S. box office prospects will be fleeting, likely no more than a blip among the upcoming onslaught of product."

Best known for the "Toxic Avenger" series, Troma is everything "Totoro" isn't. Cheap, ultraviolent, and gleefully offensive, it's quite possibly much the last studio you'd expect to see slap their name on Miyazaki's serenely beautiful fairy tale. It's not totally unprecedented: One of the all-time greatest B-movie makers, Roger Corman, had a side gig bringing art-house classics from directors like Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman to the US. But that doesn't make it any less funny to see the same name on "Totoro" that audiences associate with "Tromeo and Juliet."

My Neighbor Totoro saved the forest that inspired it

"My Neighbor Totoro" is a cult classic in the USA, but it's nothing short of a cultural juggernaut in its homeland, and that fandom has been powerful enough to save Totoro's forest from development.

Anime News Network reported in 2022 that the city of Torozawa was able to crowdfund part of the 2.6 billion yen ($19 million) needed to buy almost 400,000 square feet of Furusato Forest (what Miyazaki has called "The landscape that gave birth to Totoro") and turn it into a protected woodland.

Studio Ghibli mobilized the fundraising campaign, with Miyazaki himself putting up 300 million yen ($2.23 million) to save the forest. The fans are stepping up: As of this writing, they've already passed the 25,000,000-yen target goal. Miyazaki has always been an environmentalist with parables like "Princess Mononoke" and "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind," so it's little surprise he has put his money where his mouth is. The filmmaker has even personally volunteered for cleanup efforts.

Kids can explore the house and Catbus

The locations in "My Neighbor Totoro" are realized so vividly that many viewers find themselves wishing they could explore them in real life. The good news is Ghibli has provided opportunities for them to do exactly that.

The Ghibli Museum, in the suburbs of Tokyo, includes a stationary Catbus for visitors to "ride." Meanwhile, Nagatuke's Ghibli Park, scheduled to open in November 2022, will feature its own Catbus, along with a whole section called Dondoko Forest devoted to the world of "My Neighbor Totoro." Other areas will focus on such classic Ghibli fare as "Spirited Away," "Princess Mononoke," and "Howl's Moving Castle."

Originally created for a smaller-scale exhibit for the 2005 World Expo, Dondoko Forest includes a full replica of Mei and Satsuki's house in the middle of a real forest. Unfortunately for adult fans, all this has been scaled down to child size.

The Jim Henson Company is bringing Totoro to the stage

It's hard to imagine anyone but Hayao Miyazaki overseeing "My Neighbor Totoro," but if any other filmmaker could have combined Miyazaki's insight into children's inner life and an ability to bring it to life through vivid, unique characters, Muppet creator Jim Henson would have been a kindred spirit.

Henson died without ever collaborating with Miyazaki. Nonetheless, his successors at the Jim Henson Creature Shop might just give fans the next best thing.

Deadline reported in June of 2022 that the Creature Shop is hard at work creating effects for the Royal Shakespeare Company's adaptation of "My Neighbor Totoro," set to debut in London in October 2022. Leading the team is British-born puppeteer Basil Twist, whose resumé ranges from an experimental underwater puppet show based on Hector Berlioz's "Symphonie Fantastique" to effects for big Broadway shows like "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory" and "Beauty and the Beast."

But those aren't the only hot talents attached to the project. Joe Hisaishi, the composer responsible for the movie's haunting electronic score, has signed on as executive producer, and the show will include his original compositions, as well as outtakes that have never been heard before outside Studio Ghibli.

Director Phelim McDermott is keeping coy about how he and the Henson team will bring some of the movie's most fantastical moments to the stage. Asked about how the Catbus will fly, he simply responded: "It's theater magic."