The Ending Of Apocalypse Now Explained

"Apocalypse Now," director Francis Ford Coppola's tour-de-force 1979 Vietnam War epic, is a singular cinematic achievement and serves as a closing chapter for the New Hollywood maverick filmmaking era of late '60s and 1970s. Its surreal and hallucinatory take on author Joseph Conrad's 1899 novella "Heart Of Darkness" transposes the book's themes of 19th-century European colonialism in Africa and examination of morality and the human psyche to the United States' brutally imperialistic military conflict in Southeast Asia.

The chaos and moral ambiguity of the war itself were certainly reflected in Coppola's fraught efforts to finish shooting the film and edit it into a coherent final statement. Throughout the film's bloated and costly production, Coppola made countless revisions to the script and struggled with the ending. He has tweaked the film many times over the decades, both adding and subtracting considerable footage. The ambiguous ending to the movie has also gone through several permutations. So here's a "real choice mission" for you: Let's head upriver and take a look at the alternate endings of "Apocalypse Now," and remember, "Never get off the boat!"

Willard's journey into the heart of darkness

"I wanted a mission, and for my sins, they gave me one." In the opening scenes of the film, we learn that after special operations soldier Capt. Benjamin Willards' (Martin Sheen) first tour in Vietnam, his life back home has completely fallen apart. He's a broken man unable to function at all in civilian life, and his wife has divorced him. He's become utterly seduced by the primal lure of the jungle, and he's eager to once again return to war, where the normal constraints of society don't exist. Willard is called upon to make a literal journey into dangerous and unknown territory, a journey intertwined with and reflected by the internal journey into the dark places of his own psyche and being.

Willard knows his assignment to find and kill Col. Walter Kurtz (Marlon Brando), an Army Special Forces officer who's gone insane, is risky. The increasingly violent trek up the Nùng River fuels Willard's growing desire to confront him. When he finally drifts ashore to Kurtz's Cambodian outpost, Willard is physically and psychologically tortured, his suffering priming him to receive the truth of war in a way the outside world is not ready to accept. His morality challenged and his primordial instincts awakened, Willard completes his mission by killing Kurtz. He leaves the outpost having realized Kurtz's version of the truth; however, it's not known if Willard will ever share what he's learned in the jungle.

The horror of Col. Kurtz's final moments

Throughout his remarkable life of military service and discipline, Col. Kurtz has been "outstanding in every way." His achievements were meant to secure him a position of power and wealth in conventional society supported by the military-industrial complex; he'd been "groomed for a top slot in the corporation." But when he finds himself fighting in the jungle unchecked by the normal chain of command, free of the normal societal constraints and surrounded by natives who treat him like a god, he recognizes the fundamental dishonesty, hypocrisy, and corruption of the imperialistic structures he'd been trained to uphold.

Within the confines of his Cambodian outpost, Kurtz's soul becomes corrupted by absolute power, and he is consumed by his darker human impulses. Still tethered to his old life, Kurtz contemplates whether or not his son will ever be able to understand why his father abandoned his life of military achievement. At Kurtz's core, he remains a soldier. He understands, if not outright welcomes, Willard's mission to kill him. As he lays dying, all he can do is look into the dark abyss of his being and proclaim "the horror, the horror."

The ending's literary influences

"Apocalypse Now" is loosely based on the Joseph Conrad novella "Heart of Darkness." Moving the story from 19th-century Africa to 20th-century Vietnam, director Francis Ford Coppola uses Conrad's novella as the structural foundation for his film. In "Heart of Darkness," Marlow journeys down the Congo River in search of an ivory trader turned self-fashioned demigod named Mr. Kurtz. "Apocalypse Now" follows a similar trajectory, with Willard journeying through Southeast Asia to find and kill Col. Kurtz. Willard's trek up the river guides viewers through a sampling of life in the Vietnam War.

In the ending of both "Heart of Darkness" and "Apocalypse Now," the protagonists confront their version of Kurtz. Corrupted by power and tyrannically ruling over their followers, Mr. Kurtz and Col. Kurtz are fundamentally changed by their experiences in the jungle. Both utter the same final words — "the horror, the horror" — as they contemplate death, drifting off into the unknown odyssey of the afterlife.

War as a journey into self

"Apocalypse Now" is not your usual action-packed, shoot-'em-up war film. In "Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," director Francis Ford Coppola shares that, yes, he wanted to create a thrilling, entertaining cinematic experience for audiences, but he also wanted to answer the moralistic philosophical questions the story proposed. His wife, documentarian Eleanor Coppola, puts it succinctly by saying that "Apocalypse Now" is a "journey into self." The film's journey centers Willard's internal and external odyssey into the depths of the Vietnam War. Witnessing Willard's tumultuous trek accompanied by the narration of his innermost thoughts asks viewers to confront and challenge their own assumptions about the nature of war.

In the film's final act, Kurtz reflects on the brutality and violence he's seen, pontificating to Willard about the nature of "horror and moral terror" humans inflict on themselves during the throes of organized conflict. Kurtz, while recognizing the sheer gruesomeness of their acts, also admires the strength of men who could commit such atrocities. He welcomes death as the conclusion of his self-journey — his inability to reconcile humanity's propensity for extreme love and death becomes too much to bear.

Francis Ford Coppola thought the film's original ending was weak

In the documentary "Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," director Francis Ford Coppola expresses his dislike for the film's original, scripted ending, saying, "I never cared for the ending so much. I thought the ending was weak." As written in John Milius' screenplay, "Apocalypse Now" concluded with an intense gun battle between Willard, Kurtz, and the Viet Cong. Kurtz shoots down the helicopter sent to take him out of the fight, declaring his allegiance to his own carnal power. Coppola dismissed it as a "macho, comic book kind of ending."

Coppola's discontent with the finale caused him much strife. He even quips in the documentary that "Apocalypse Now" should be called "The Idiodyssey" for his struggle to make the finale work. Ultimately, Coppola recentered the ending around the film's literary source, "Heart of Darkness." Coppola stayed true to his initial concept for the film, merging Milius' screenplay with "Heart of Darkness" and embedding within it the real-time experience of filming in the Philippine jungle.

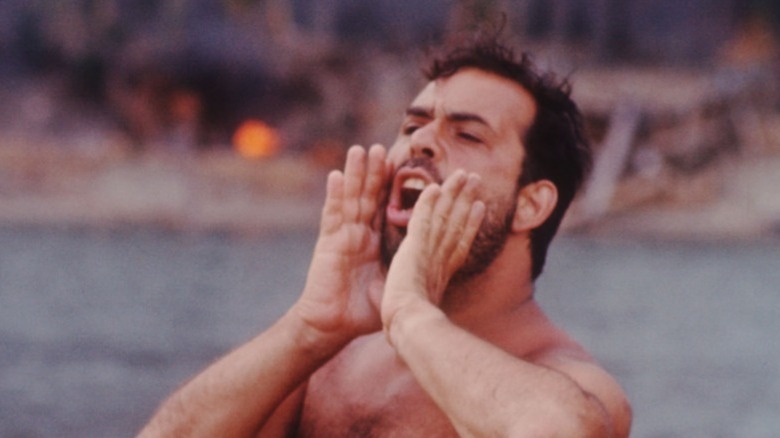

The use of The End by The Doors

"Apocalypse Now" is bookended by the haunting rock 'n' roll sonic odyssey "The End" by The Doors. With the slinky vocal stylings of Jim Morrison guiding listeners through a nearly 12-minute Oedipal vision quest, crescendoing in primal screams and pounding percussion. The film's opening scenes unfold with "The End" juxtaposed with fiery jungle explosions, the haunted memories of Willard's experiences at war. When Willard kills Kurtz in the film's violent finale, the slashes of his machete sync to the song's rattling, thrashing conclusion. Truly, it is the end for Kurtz.

As noted in the book "The Doors FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock," director Francis Ford Coppola was aware that The Doors' music was part of the soundtrack of the Vietnam War. He wanted to use their song "Light My Fire" in "Apocalypse Now" but ultimately, it was "The End" that made the final cut, and totally by accident. Coppola says in a commentary track that while wandering around the editing room, he found footage of napalm explosions bound for the garbage, and had the thought, "wouldn't it be funny if I took a song called 'The End' and put it at the beginning of a movie?" A poignantly authentic improvisation, Coppola's use of "The End" brilliantly encapsulates the film's surreal journey into darkness.

Marlon Brando and Francis Ford Coppola's clash over Kurtz shaped the finale

Marlon Brando, one of many nightmares to plague the production of "Apocalypse Now," nevertheless became more of an icon for his role in the film. He'd previously starred in another of Francis Ford Coppola's endearing classics, "The Godfather." Released in 1972, the film resurrected Brando's flailing career and made Coppola one of Hollywood's hottest directors. With Hollywood's renewed interest in his formidable talents, Brando was once again charging top-dollar for his services. Back in demand after "The Godfather," Brando signed onto "Apocalypse Now" for a $1 million-per-week fee (via Deadline). However, garnering such an exorbitant fee wasn't necessarily a guarantee of his professionalism.

Brando arrived at the "Apocalypse Now" set overweight and underprepared. He and Coppola collaborated for hours to develop Kurtz's dialog, but then Coppola realized Brando hadn't read the film's source material, "Heart of Darkness." Vanity Fair reports production was held up for several days as they debated Kurtz, a costly prospect on an already financially burdensome production. Brando sent Coppola into such despair that he feared the whole film would need to be scrapped. But according to HuffPost, Brando buckled down, read "Heart of Darkness," and contributed ideas. Brando's filmed improvisations for Kurtz molded the ending of "Apocalypse Now" in fascinating, unpredictable ways. Because Brando's physique wasn't what Coppola had envisioned for the character, Coppola hid him in shadows and silhouettes, the chiaroscuro lighting adding more mystery to the enigmatic Kurtz. Coppola reflected to Vanity Fair about Brando, "People say he gave me trouble, but he was an extraordinary man who made an extraordinary contribution with his creativity and his genius."

The movie actually has two filmed endings

"Apocalypse Now" debuted at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival as an incomplete film. Director Francis Ford Coppola sees his film as "more philosophical and less realistic" depiction of war (via The New York Times). When it was time for the movie's release, The New York Times reports that Coppola and editor Walter Murch were under pressure to deliver a completed action-war film. Figuring out the right ending proved elusive to Coppola, as he told The New York Times, "Working on the ending is like trying to crawl up glass by your fingernails.” Eventually, Coppola and Murch sent "Apocalypse Now" to Cannes unfinished. Not that anyone cared. It won the festival's top prize, the Palme d'Or, an honor it shared with "The Tin Drum."

"Apocalypse Now" was completed and released after Cannes, but an issue arose during the editing process: The film had two endings. Coppola details that the film was previewed with an ending that showed Kurtz's compound destroyed in a fiery inferno, a credit sequence rolling over the carnage. However, Coppola decided the warlike destruction didn't support his vision for Willard, and his original ending concept never included end credits. This explosive finale had a wide release, mostly to include credits, but it was quickly modified to reflect Coppola's initial vision. He asks that it not be considered an alternate ending to the film, but rather a stand-alone filmmaking exercise (via YouTube).

The meaning of the film's title

Regarding the actual meaning of the film's title, "Apocalypse Now," co-writer John Milius has explained that it predated the conception of the film and was inspired by the lapel badges he saw hippies sporting during his time at USC film school — he had the title, "Apocalypse Now," because the hippies at the time had buttons with peace signs that said "Nirvana Now."

Milius' words track with the modern English meaning of the word "apocalypse" connoting a massive, destructive cataclysm perhaps viewed as a prophetic revelation. Milius' classic lines like "I love the smell of napalm in the morning" and his ferociously destructive helicopter attack scene also support this interpretation. Yet the word "apocalypse" has its roots in the Greek word apokálupsis, which means "uncovering" or "revealing." Although Coppola and Milius have perhaps not made this explicit connection, one could postulate that for both Willard and Kurtz, the war has stripped away their inner illusions and justifications to reveal the hypocrisy and immorality of their imperialistic war.

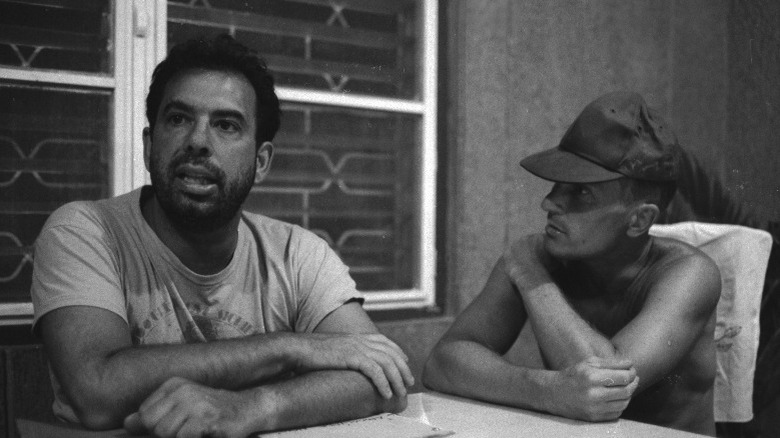

The making of Apocalypse Now set a precedent for filmmaking debacles

The making of "Apocalypse Now" was a notoriously challenging experience. Chronicled in the 1991 documentary "Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse," the creation of this cinematic masterpiece was a near-Sisyphean task. Work on the film began in the late 1960s during the Vietnam War, but the film was shelved until 1975. Produced independently by Coppola's American Zoetrope, the filmmaking process for "Apocalypse Now" was liberated from traditional studio mechinations. But this freedom meant Coppola was responsible for every aspect of the film, including its financing, with Variety reporting the budget ballooned from $12 million to over $30 million. The 238 days of principal photography "Apocalypse Now" underwent in the Philippines were riddled with drama. From casting problems, weather issues, and uncooperative collaborators, Coppola had his hands full.

The production of "Apocalypse Now" set a precedent for filmmaking debacles. Like "Apocalypse Now," other films' troubled productions have received making-of documentaries. 1996's "The Island of Dr. Moreau," also starring Marlon Brando, was plagued with problems. The documentary about the making of that film, "Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley's Island of Dr. Moreau," shows that the behind-the-scenes story is often just as compelling, if not more so, than the finished product. Equally insightful and just as frustrating is "Lost in La Mancha," the documentary about Terry Gilliam's almost-doomed attempt to bring Don Quixote to the big screen. Neither "The Island of Dr. Moreau" nor Gilliam's completed film "The Man Who Killed Don Quixote" are masterpieces like "Apocalypse Now," but like Coppola's film, it's a miracle they exist.

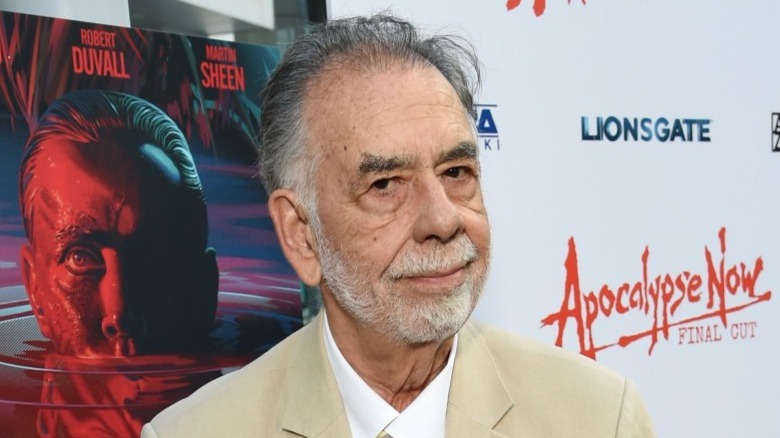

New editions of Apocalypse Now mean the movie lives beyond its ending

"Apocalypse Now" is arguably Frances Ford Coppola's singular filmmaking vision. Not only did he direct, produce, and co-write the movie, but he also owns the rights to it in perpetuity (via Variety). Since Coppola retains sole ownership of the movie, he can do what he wants with the project. Coppola reflected to Vanity Fair that he made the initial 147-minute 1979 cut of "Apocalypse Now" in the spirit of compromise, saying, "I felt that in my lust to make it shorter and less weird back then, I removed so many important things." Culled from a roughly four-and-a-half-hour rough cut, this highly shortened version of the film was only its first iteration (via The New York Times).

Editing comes naturally to Coppola, who shares with Vanity Fair, "My feeling was that to get 'Apocalypse Now' to light up as an experience for the audience just required some tweaking." In 2001, Coppola released "Apocalypse Now: Redux," adding 53 minutes of footage back to the film. New scenes were added and the print was refreshed using the latest Technicolor technology. Of "Redux," Coppola said, "You see more facets of themes of hypocrisy and morality, and the ending works better." Nearly two decades later, he went back to the editing room to create the third iteration of the film. "Apocalypse Now: Final Cut" was released in 2019, trimming sequences that might not resonate with contemporary audiences, like the medevac scene and Kurtz reading an excerpt from Time magazine.

It ushered in a new era of filmmaking about the Vietnam War

When "Apocalypse Now" was released in 1979, the Vietnam War was fresh in America's collective memory. Amidst growing disillusionment with and increased protest against the war in Southeast Asia, Hollywood struggled to depict it on screen. When it tried, like with the John Wayne star vehicle "The Green Berets," it failed in the extreme, with Roger Ebert boldly exclaiming, "It is offensive not only to those who oppose American policy but even to those who support it." The valor and pageantry of Hollywood's post-World War II cinematic output weren't ready to deal with the social and political complexities Vietnam War-era storytelling would require. According to George Lucas and "Apocalypse Now" co-writer John Milius in the making-of documentary, Hollywood actively rejected making "Apocalypse Now" during the Vietnam War, musing that studios feared tackling the controversial conflict.

By the late 1970s, movies portraying not only the actual war but also its aftermath made their way to audiences. The 51st Academy Awards was dominated by a duo of Vietnam War films "The Deer Hunter" and "Coming Home," both films winning a slew of Oscars for their emotionally impactful stories. The following year, "Apocalypse Now," with its bold and unflinching depiction of the horrors of war, set a new precedent for Vietnam War movies. By the 1980s, Hollywood embarked on a Vietnam War artistic reckoning with gritty films like "Platoon," "Full Metal Jacket," and "Born on the Fourth of July." In subsequent decades, countless films about the conflict have been made, but "Apocalypse Now" remains one of the best movies about the Vietnam War.