Everything Blonde Gets Wrong About The True Story

The following article includes discussions of child abuse, mental illness, sexual assault, domestic violence, abortion, drug use, and suicide.

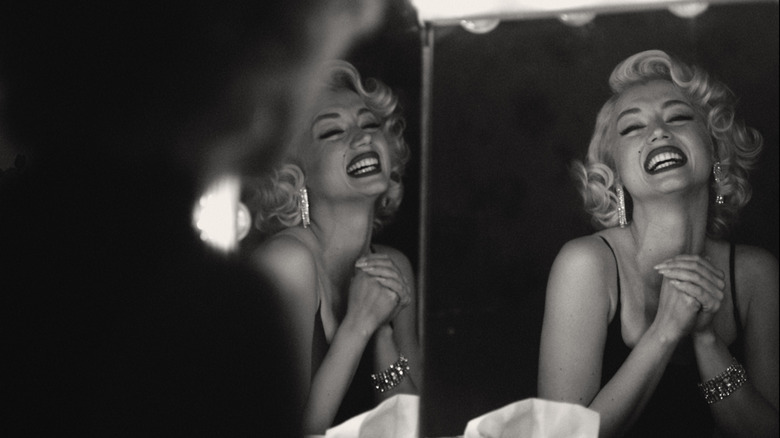

Andrew Dominik's "Blonde" is not for the faint of heart. Based on the 2000 novel of the same name by Joyce Carol Oates, the film is a bleak and unsparing look at the tragic life of actress and icon Marilyn Monroe (Ana de Armas), from her traumatic childhood in the Great Depression to her death by drug overdose in 1962 at age 36. Dominik and his collaborators, including cinematographer Chayse Irvin and production designer Florencia Martin, have crafted a film that's beautiful to look at but often difficult to watch, casting Monroe as a woman whose ambitions were thwarted by an industry that only saw her as a sex object and someone whose obsession with an absent father kept her falling into one abusive, exploitive relationship after another.

Whether or not this is accurate to Monroe's life is, in a way, beside the point. Oates' novel is very much a work of fiction that uses the bones of Monroe's biography in service of a more poetic consideration of her life and death, and Dominik's screenplay condenses that 700-plus page book into a film that runs just over two-and-a-half hours. Liberties with the historical record have obviously been taken, but in a way, that's more intentional and complicated than simply getting the facts "wrong." Let's look at some of the ways "Blonde" departs from the true story of Marilyn Monroe.

Marilyn Monroe's father

The film attributes much of Marilyn Monroe's inner torment, professional ambition, and dysfunctional relationships to an obsessive search for the father she never knew. Early on, her mother Gladys (Julianne Nicholson) shows a young Norma Jeane Mortenson (Lily Fisher) a framed photograph of a dashing older man. This man is her father, Gladys tells her, a powerful man in the movie business but whose name she can never tell. Monroe will spend the rest of her life seeking him out, both literally (combing through old studio headshots looking for his face) and figuratively (in the older men and lovers she calls "daddy"). At the height of her stardom, she begins to receive letters from a man claiming to be her father, and the cruel revelation of the letters' true author is the push that sets Monroe toward taking her own life.

While it's true that Monroe was raised without a father (and, most of the time, without a mother), in real life, she strongly suspected her father was a man named Charles Stanley Gifford, whom Gladys had an affair with while working as a film editor at RKO Pictures. In 1952, Monroe even attempted to contact him, according to biographer Charles Casillo (via Vanity Fair), and the anonymous letters signed "Tearful Father" are an invention of the novel and film. In 2022, a French DNA researcher apparently proved that Gifford and Monroe were related; his findings were broadcast in the documentary "Marilyn, Her Final Secret."

Marilyn Monroe's mother

Marilyn Monroe's fraught upbringing with her mother Gladys is represented primarily by two hellish, frightening sequences early in the film — one where Gladys puts young Norma Jeane in their car and attempts to drive into the Griffith Park wildfire of 1933 and another when she tries to drown her daughter in the bathtub. After the bathtub incident, Gladys is hospitalized and confined to a mental institution for the rest of her life. Norma Jeane, after being cared for by her neighbors (Sara Paxton and Ryan Vincent) for a short time, is dropped off at an orphanage. When she sees her mother again, 10 years later, Norma Jeane has transformed fully into Marilyn, and Gladys — in the throes of schizophrenia — doesn't recognize her.

While the specific incidents presented here may not be confirmed, both Gladys and her mother, Della Monroe, were known to have violent outbursts related to mental illness. Monroe's earliest years were mostly spent in the care of family friends. In an incident detailed in J. Randy Taraborrelli's book "The Secret Life of Marilyn Monroe," Della talked her way into the home where infant Norma Jeane was living and tried to smother her with a pillow. Later, when Norma Jeane was 3, Gladys attempted to abduct her by stuffing her in a duffel bag. After Gladys was institutionalized in 1934, Norma Jeane was a ward of the state, living in orphanages and foster homes before being taken in by family friend Grace Goddard at age 11.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services

Mr. Z

After years spent as a pin-up model, Marilyn Monroe's big break comes when she's offered an audition for a studio mogul referred to as Mr. Z (David Warshofsky). Stepping into an intimidating office full of taxidermied animals, Monroe nervously reads her script in front of a silent Mr. Z until the man steps behind her, still without a word, and sexually assaults her. Later in the film, when she's talking about the beginning of her career with the Ex-Athlete (the film's stand-in for second husband Joe DiMaggio, played by Bobby Cannavale), she flashes back to this moment and simply tells him that she was "discovered."

Mr. Z is by all accounts an avatar for 20th Century Fox head Darryl F. Zanuck. Monroe was under contract at Fox for much of her film career, and she and Zanuck are known to have had a difficult working relationship. Monroe bristled at the "dumb blonde" role she was regularly offered, while he considered her simply that — a dumb blonde. And while tales of the "casting couch" were common in Hollywood both then and now, according to biographer Anthony Summers, there's no evidence that Zanuck assaulted Monroe in this manner. As to her being "discovered," Fox's official story was that she'd been discovered while babysitting for a casting director, initially hiding the fact that she'd been a pin-up and occasional nude model for years before being cast in her first film.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

Don't Bother to Knock

In "Blonde," Marilyn Monroe is seen in 1951 auditioning for the Richard Widmark thriller "Don't Bother to Knock." In a tight close-up mimicking the angle of the screen test's camera, Monroe gives an intense, soul-baring monologue. The role is uncomfortably close to her own life — a woman whose mother was abusive and whose father had abandoned her long ago. After she's done, she pleads for another chance but is taken away by her manager, I.E. Shinn (Dan Butler). The crew is dumbfounded by what they saw as a terrible performance, but the director (Garret Dillahunt) is captivated by her looks.

The scene treats Monroe as if she's an unknown at this time, if not stepping in front of the camera for the first time. In reality, she was a sensation almost from the moment she appeared on film, and the year before, she'd made two of her most notable early movies, "All About Eve" and John Huston's noir "The Asphalt Jungle." She'd even weathered a scandal involving nude photos she'd posed for in 1949. As for "Don't Bother to Knock," the film received mixed reviews, but Monroe's performance was singled out for praise, with Variety writing, "Marilyn Monroe ... gives an excellent account of herself in a strictly dramatic role."

Cass and Eddy G.

Marilyn Monroe was romantically linked to any number of Hollywood luminaries in the early 1950s before her relationship with Joe DiMaggio, including Marlon Brando and director Elia Kazan. The film represents this time in her life by focusing on an unconventional romance with two show business scions: Charlie Chaplin Jr., nicknamed Cass (Xavier Samuel), and Edward G. Robinson Jr., known as Eddy G. (Evan Williams). Monroe envies them because everyone in the world knows who their fathers are, while Cass and Eddy G. envy her for the fact that she's an orphan and can make herself into anything she wishes. The three do everything together, and when Monroe gets pregnant, they celebrate as a group.

Monroe was involved with Chaplin in real life for a short time, according to biographer Anthony Summers, but the relationship apparently came to an end after she had an affair with Chaplin's brother. Robinson isn't known to have dated Monroe or Chaplin, either separately or in the polyamorous triad the film depicts. The film also has Chaplin dying before Monroe, and in a posthumous communication to her, he reveals that he was the author of all the letters her "father" wrote to her. In real life, Chaplin would outlive Monroe by six years, dying in 1968 at age 42.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

In the film, Marilyn Monroe balks at her contracted $500/week salary for appearing in Howard Hawks' musical "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes" when she learns that co-star Jane Russell is making $100,000. After all, she's the blonde of the title. But there are other complications in taking the role beyond money. Her pregnancy is a professional barrier, and she also fears that her mother's mental illness could be hereditary. At the studio's insistence, Monroe decides to terminate the pregnancy, leading to the first of the film's two graphic abortion sequences.

Verifying the accuracy of Monroe's abortions, or even if she had any, is difficult. It was illegal nationwide to terminate a pregnancy in 1953, and the notion that Monroe had several abortions in the course of her life was popularized by author Gloria Steinem in her 1986 biography "Marilyn: Norma Jean" (via Vulture). However, it is known that Monroe was paid considerably less for her star-making role in "Gentlemen Prefer Blondes," one of many small insults during her time under the thumb of Darryl F. Zanuck and a large part of her motivation to break her contract with Fox and start her own production company, a chapter in her life that the film ignores, along with any other sense that Monroe was an active participant in her own career.

The Playwright

After Marilyn Monroe's abusive marriage to the Ex-Athlete ends in divorce, she retreats to New York City to study acting. When the Playwright (the film's stand-in for Arthur Miller, played by Adrien Brody) sees her in a reading of one of his plays, he assumes that she's been cast because the director (unnamed but assumed to be Elia Kazan) is in love with her. But as the lights come up after the reading, the Playwright is in tears at her performance (which we do not see). Monroe impresses him with how well-read she is (once again coming as a surprise), while she connects to his gentle intellectualism — a complete opposite from the prudish brutality of the Ex-Athlete. The two marry in 1956.

The film frames the play reading as the first time they meet. The Playwright has heard of her, obviously, but they don't know each other. In real life, Miller and Monroe met in Los Angeles in 1950, introduced by Kazan. The two would correspond off and on over the years (via Biography) until reconnecting in New York in 1955 while Monroe was studying at the Actors Studio and managing her own production company. Miller, however, was married at the time of their affair and under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee for alleged communist affiliations. Monroe stood by him through both his divorce (which led to him living in Nevada for a portion of 1956) and his legal troubles, none of which is given any space in Andrew Dominik's film.

Miscarriage

Marilyn Monroe's early marriage to the Playwright is idyllic, filmed in widescreen and full color as they frolic on New England beaches. She soon becomes pregnant and is hopeful for the future, even if the mistakes of her past still weigh on her. This feeling is dramatized in the instantly notorious scene in which she hears the voice of her fetus as it begs her not to abort it like she did the last time. When friends of the Playwright's come to visit them, Monroe is nervous about spending time with them, even as he assures her that they are there to see both of them. Her apprehension proves prophetic when she falls on her stomach while bringing a plate of crudite out to their friends on the beach. The fall causes her to bleed profusely from her stomach. In a panic, she screams for the Playwright to save their baby.

While Monroe's possible abortions aren't a matter of public record, her failed pregnancies with Miller very much are. She suffered miscarriages in both 1956 and 1958 and had an ectopic pregnancy that didn't go to term in between. In real life, Monroe's feelings on motherhood were ambivalent. She wrote in her posthumous memoir "My Story" (via Vanity Fair) that at one time, the thought of being a mother "stood [her] hair on end," as she could only envision childhood as she experienced it — as an unloved foster child. Later in life, however, her view softened, and even after the end of her marriage to Miller, she welcomed the idea of being a mother.

The President

The affair between Marilyn Monroe and John F. Kennedy has always been the stuff of second-hand reports and urban legends rather than established fact. According to Donald Spoto's comprehensive 1993 biography of Monroe (via PopSugar), the two were only ever seen in public together four times. Biographer Anthony Summers, on the other hand, treats it very much as fact that she was involved with both JFK and his brother, Robert, that her final days were preoccupied with thoughts of both men, and that JFK may have even visited her in California shortly before her death.

The film dramatizes her alleged relationship with Kennedy (known here as "The President," played by Caspar Phillipson) via a nightmarish sequence in which an inebriated Monroe is escorted off an airplane by Secret Service agents, literally dragged through the back hallways of a New York hotel ("Am I a piece of meat being delivered?" she quips, echoing something the Ex-Athlete once said), and placed in the President's hotel room where she's essentially forced to do something against her will. Afterwards, she's escorted right back out by Secret Service. That nightmare feeling continues in a following scene where she dreams of men kidnapping her in the middle of the night and forcibly removing what we're to assume is her baby with the President, the second of the film's explicit and disturbing abortion scenes.

The car wreck

After her (possible) nightmare involving her kidnapping and abortion, an increasingly pill-dependent Marilyn Monroe drives through Hollywood, presumably on the Fourth of July. As children play with sparklers, she sees the face of her possible father (Tygh Runyan) — the man in the picture that hung above her bed as a child — beaming proudly from every front yard. She becomes so preoccupied with these visions that she crashes her car headlong into a tree and wanders, dazed, into the street.

There's no evidence that such an accident took place. However, the sequence may be drawing inspiration from the tragic tale of reporter Mara Scherbatoff. According to Jaquo, in 1956, Scherbatoff, a photographer, and their driver were traveling outside Roxbury, Connecticut, to cover an announced press conference by Monroe and Arthur Miller. Scherbatoff, eager for a scoop, tracked the couple's car and pursued it through the winding country roads. The driver lost control of the vehicle, and the car slammed into a tree. Miller and Monroe were the first people on the scene. Scherbatoff was seriously injured and would later die in a nearby hospital. Miller and Monroe continued with the scheduled press conference, though existing footage presents a clearly distraught couple.

Accident or suicide?

During "Blonde," it's 1962, and Marilyn Monroe receives a call from Eddy G. with the sad news that Cass has died. He informs her that Cass left her something and to watch out for a delivery. When that delivery comes, it's an old stuffed tiger like the one she had as a girl, along with a note containing a terrible, cruel confession: Cass was the one writing letters to her, claiming to be her father. The revelation sends Monroe into a tailspin of anguish. Standing by the pool of her Hollywood home, she swallows dozens of pills, one after the other. She strips off her clothes and climbs into bed, takes the phone off the hook, and passes out. As she slowly dies, she has a vision of the man she thought was her father, his face beckoning her from the heavens.

As noted above, Monroe knew who her father was and neither Cass nor anyone else wrote her letters like that. The entire sequence, other than the condition Monroe's body was found in, is a flight of fancy. So what might have happened? The Los Angeles coroner at the time ruled her death a "probable suicide" due to the sheer amount of barbiturates she'd ingested. Yet her personal correspondence from that time, collected and published in 2010 as the book "Fragments," shows a side of her that finally felt on firm ground, leading credence to the idea that her death was accidental (via Vanity Fair). As for the belief that she was murdered, possibly by the Kennedys due to her knowledge of state secrets, the film does not engage with any of that.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Marilyn Monroe the artist

One of the biggest controversies that's sprung up around "Blonde" is the way that the film dismisses most of Marilyn Monroe's accomplishments as an artist and businesswoman in favor of scene after scene of abuse and degradation. Little in the film would inform an audience at what a talented comic and dramatic actor Monroe was or the accolades she received when she was alive. The film details her outbursts and meltdowns during the reportedly difficult production of "Some Like It Hot" but not that Monroe won a Golden Globe for her performance or that she was nominated for her performance in the film "Bus Stop" in 1957, an acclaimed film that "Blonde" doesn't even mention.

The film omits any detail about Monroe's feud with Darryl F. Zanuck over the quality of roles she was getting at 20th Century Fox, a battle that resulted in Monroe forming her own production company in New York. This audacious move is seen in hindsight as playing a part in the end of the "studio system" that kept actors — even megastars like Monroe — beholden to exploitative and unfair contracts. In glossing over Arthur Miller's leftist politics and struggles against McCarthyism, the film also shortchanges Monroe's own progressive streak and her work with organizations like the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy. No film can cover every facet of a person's life, but so much of what made Monroe a lasting icon, rather than a mere body to be abused, seems to have been left out of the film.