The Ending Of The Midnight Club Explained

Mike Flanagan loves writing stories about stories. "The Haunting of Hill House" revisits childhood trauma through modern-day stories, and "The Haunting of Bly Manor" literally takes the form of a ghostly tale told by firelight.

"The Midnight Club" is made up of stories within stories about stories, like a hall of spooky mirrors, and when the stories start to bleed together, that's when things get serious. In fact, one of the most ambitious (or gimmicky, depending on how you look at it) episodes of all, the premiere, ironically titled "The Final Chapter," ends with a series of metafictional jump scares so intense that it found its way into the Guinness Book of World Records.

By the end of the season, a lot of our questions are answered, but not all of them. Let's take a look at each member of the Midnight Club, as well as their allies and enemies, and see how each of them finishes the season.

Spoilers on the way for Season 1 of Netflix's "The Midnight Club."

Many sides of hope

Ilonka is the main lens through which we view most of the season. She starts "The Midnight Club" as her school salutatorian on the cusp of graduation. Then she discovers she has cancer, and slowly watches as the high school life she knew — along with all its friendships and crushes and disappointments — fades away.

It's a harsh introduction to a pretty harsh show, and one that tells us the stakes early; each of the characters we're about to meet and fall in love with has a terminal illness, and therefore may very well die in the foreseeable future.

The main mystery plots — what happened to Julia Jayne, the whereabouts of Athena and Aceso, the ritual of the Five Sisters, and whether Dr. Stanton is hiding anything — are all centered around Ilonka because she is the clubber most stubbornly addicted to the idea of spontaneous recovery. After all, it's the story of Julia Jayne that attracts her to Brightcliffe in the first place.

In the end, Ilonka narrowly escapes death by following her instincts and intuition, which serve her well throughout the story. While her journey doesn't necessarily feel complete, it does end on a high note. As Kevin says, her stubbornness about finding a cure is just part of what makes her such a potent symbol of hope.

The liar tells the truth

Let's talk about Cheri — a natural storyteller or a chronic liar, depending on your point of view. As the season unfolds, Cheri never really takes center stage, although her particular storytelling episode was as twisty and stylized as any we see on the show. But what Cheri is dealing with in reality is the end of stories.

By the end of the season, we learn many of Cheri's seeming lies are actually true. Her parents are rich and famous, she plays the cello, and her family doesn't care about her. It's one grace note in a show full of many. Saintly nurse practitioner Mark gently pushes back against Cheri's lies but shows her complete respect and love regardless. Cheri's ultimate "sacrifice" is an admission of her own queerness, which marks the end of another kind of painful story.

Mark bonds with Cheri over the meaningless gifts and trinkets she receives in lieu of family visits on Family Day, which is also when we see the completion of her seasonal arc; she takes her place at Spencer's side as part of the real found family she has helped to build.

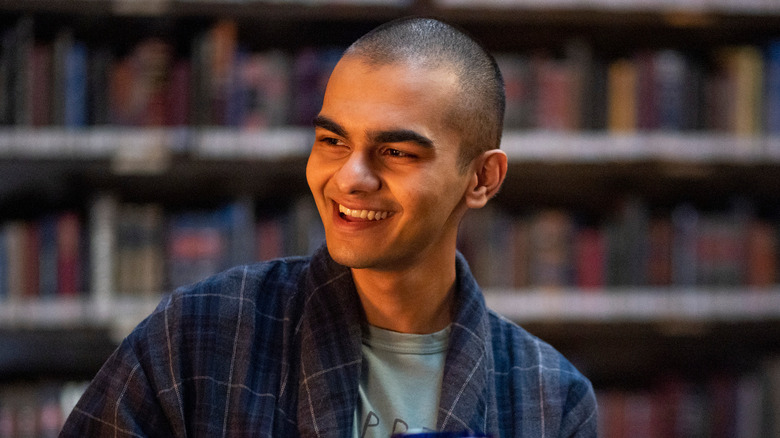

Kevin's not-so-wicked heart

Kevin is afraid of ending his stories, which emphasize his fear of hurting the people he loves. In his Midnight Club stories he's an ancestral serial killer, driven by family forces to kill every young woman he cares about. In real life, he knows it's only a matter of time before he lets his girlfriend down by dying.

Kevin's journey — beautifully acted by Igby Rigney – is very reminiscent of the famous hospice love story "The Fault in Our Stars," which is similarly about snatching moments of pleasure and joy and love out of the jaws of impending death. In the end, Kevin breaks up with his girlfriend so that he can share a kiss with Ilonka.

Kevin's story becomes one about grabbing life when and where it presents itself. Not letting death win, but letting life happen fully instead. According to the moral of multiple stories in "The Midnight Club," a full life isn't possible without coming to some kind of acceptance of death.

Natsuki embraces life

Out of the handful of depressing chapters of "The Midnight Club," Natsuki and Anya's stories are the hardest to watch. Both have an extra bit of realness to them because they're told in nonstandard ways. Natsuki is unable to share her story with the group and ends up bonding with Amesh over it instead.

Untreated clinical depression — Natsuki's other illness, which was almost terminal — gives her story-self the wrong messages about the worth of her life and future, and the rest of her tale is about coming back from that darkness. In the story, Natsuki bravely talks herself out of dying, but she admits to Amesh that in real life it was her mother who discovered her close to death and saved her, just in time for her diagnosis. We see Natsuki struggle with her need to be alone, which she symbolically breaks through by relaxing into her relationship with Amesh and with the larger group.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The new girl who survived

Sandra, of course, is a special case. She's the only member of the Midnight Club who gets to go home after her terminal illness turns out to be a misdiagnosis. This has a great impact on Ilonka and her storyline, because at first Dr. Stanton refuses to tell Ilonka who the lucky kid is, which fuels a lot of Ilonka's irrational belief in the Five Sisters ritual.

Sandra is a staple Mike Flanagan character archetype — a rational Christian who is able to acquit herself and her religion against all comers. Flanagan is always careful to explore all kinds of faith, not just the most destructive or constructive elements. Sandra's journey is a terrific example of Flanagan's thoughtful approach to religious themes.

By putting Sandra up against Spencer, whose own story involves grappling with faith and its adherents, and then Ilonka, who is finding a different faith from Sandra's, we see Sandra the way she sees herself — content in her conviction. She attends the Five Sisters ritual out of love for the group, and even finds a way to gracefully take part without letting herself or her faith down.

Gets the girl, saves the world

Amesh's "Midnight Club" story is a twisty time-traveler about oblivion. In the story, a handsome future self he'll never get to be comes back to the past to "reprogram" him in the present. He writes Natsuki into his story and experiences everything through a set of nerdy verbal and emotional cues.

In real life and in the story, he just wants to "get the girl" and "save the world." In the case of both slogans, there's a bit of surrender involved. Amesh learns — or teaches himself, you might say, just like in his story — that some games can't be won until you refuse to play, whether it's a nuclear armageddon or the hope for a cure that drives Ilonka.

The protagonists in Amesh's story end up locked together in a space station, unable to set foot on Earth. They're just like the Midnight Club in many ways, although the world-ending catastrophes for Amesh and his associates are a lot smaller in scope. But maybe that's the point of Amesh's journey — from his subjective and specific personal perspective, the world-ending catastrophe of his deepening illness is no bigger and no smaller than a nuclear holocaust.

Spencer's fears

Thematically, Spencer's story and his personal journey both combine the AIDS epidemic with plotlines from the "Terminator" franchise and other sci-fi tropes. In Spencer's story, the charming nerd Christopher is so inspired by their love that he creates a future world free of fear or pain.

That's a kind of heaven that Spencer will never know, because he is a cyborg creature that only thinks he's in love with Christopher; the truth is that he has been sent back in time to destroy him. Of course, the older cyborg version of Christopher has only come to destroy Spencer.

We see all this before the big reveal that it was the real-life Christopher who infected Spencer with HIV, placing him on the path to Brightcliffe and putting him at odds with his biological family. This discovery recontextualizes the story and problematizes it in a fascinating way; in the story, Spencer has to die so that the young, human version of Christopher can live.

The real world will never be free of pain, but it could stand to lose a little fear, and that's really what Spencer's journey is about over the course of the season. Mark's kindness — particularly his impulse to share his world, his found family of friendships and activism with Spencer — gives him the bravery to change his relationship with his parents, resulting in a redemptive and kind conclusion.

Julia Jayne

"Shasta," as she's known for most of the season, is quite a character. Fans may remember Samantha Sloyan as the implacable, unbelievable Bev Keane in "Midnight Mass." In "The Midnight Club," she gives us an off-kilter feeling from the moment she steps out of the woods, ready to give Ilonka anything she needs.

Shasta's a sort of a wild and unhinged fairy godmother-type character. She mentors Ilonka in the ways of homeopathy and alternative medicine; she tempts her again and again to overlook the well-meaning and gentle rules of Dr. Stanton, and she runs what is clearly a cult of her own.

What we learn in the season's final episodes rewrites everything we thought we knew about Brightcliffe, Shasta, and the Five Sisters, as we see a young Julia visiting the original cult leader Aceso and becoming her protegee. As Julia is drawn into magic by Athena's journal detailing the original mass murder ritual, so too is Ilonka driven by the journal and Julia's own scattered clues which eventually lead to another ritual suicide. However, it is from this very same ritual that a grinning (but notably still ill) Julia Jayne escapes. At this point, you might be wondering about a second season, but that's not the last cliffhanger by a long shot.

The unbroken dancer

Anya's journey comes in two phases. First, there's her story about the two Danas, which is fairly autobiographical; one Dana is a perfectionist ballet student, the other half of herself is heroin addict, and the two are engaged in mutually assured destruction.

The second journey is, of course, the Five Sisters ritual and the bonding among the Midnight Club that precedes it, which shows that love of the worst among them brings the whole group together. The arguably ham-handed metaphor of the broken ballet statue, which miraculously turns up whole at one point, would seem to suggest that Anya's story is about being "broken" versus being "fixed." It's not the leg she grieves, but all the things she left behind when she was broken.

That's why her longer dream-story, in the episode "Anya," is so bleak — visited by the voices of the Midnight Club every night, Anya ignores the signs that her condition outside the dream is weakening, and so we get a more complete ending for Anya than we do for the others. As the only member of the Club to die during the season, she carries important meaning, and her death spurs a lot of later plot developments.

Dr. Georgina Stanton

In one of roughly five excellent, pitch-perfect performances on "The Midnight Club," the quintessential final girl of 1984's "A Nightmare on Elm Street" Heather Langenkamp plays Dr. Georgina Stanton. We spend much of the season dwelling on Stanton's kindness, her empathy, and her steady nature, so it carries extra weight when the kids start to disappoint her.

As viewers, we're privy to a lot of information about Dr. Stanton that the Midnight Club do not, and perhaps will never know. She's less innocent and less oblivious than she seems, of course. We learn, in the show's final moments, that she is undergoing chemotherapy, or at least wears a wig — something that would definitely change the dynamics within the facility if the Midnight Club knew about it.

Stanton's clinical approach to both one-on-one and group therapy is even keeled and gracious, even when her charges act out. Like Shasta, she blinks, wide eyed and curious, at any mention of the Paragon or the Five Sisters, only to eventually reveal her own complicity ... or does she?

In the end, we get two important clues. The first is that the original builders of Brightcliffe may still be around as ghosts, which is why Kevin and Ilonka both see the same elderly couple haunting the time-shifting halls. This is tied to a moment of viewer intimacy with Stanton that seems to connect her to this pair — but it's the hourglass tattoo on her neck that really has us asking what's going on.

We're left with questions

Is Dr. Stanton a member of the Paragon? A devotee of the old goddesses, like Aceso? Something older than those things? Is she related to Brightcliffe's builders? Is she an old goddess herself? Perhaps she is Athena, the daughter of the original cult leader, although that still leaves us with the question of why she would leave all those clues around for Ilonka to find.

Where does Julia Jayne get her suicidal cult members? Are they workers from her weird farm? Where does she go after escaping? How long has she been fighting to get back into Brightcliffe before Ilonka wanders across her path? What is her illness? Is it the same one from which she was originally "cured?"

What will happen between Ilonka and Kevin now that they've kissed? What will happen to Sandra, out in the wider world, and will we see her again? Is Amesh going to survive? What happens to Natsuki if he doesn't? Will Spencer find love again in the outside world Mark teaches him about? Will Cheri ever find a place to be herself?

Such an intricate story of faith, death, love, and pain must be steeped in mystery, because those are the biggest mysteries we've got. We're left with a pile of questions, but at least in Mike Flanagan, we get a filmmaker just as obsessed with those questions as we are.

A death story about life

Our relationship with stories and our relationship with death are two of the most important relationships we'll have in our lives. Stories are bounded with a beginning and an end, just like life, and we don't know what happens after either of them. Perhaps that's the meaning of this season's quirky cliffhangers — we're meant to infer that stories, and lives, don't really end at all.

We're reminded of so much other literature and film: Robert Cormier's "The Bumblebee Flies Anyway," and the rest of Christopher Pike's YA horror. But one reference that kept coming up was Kazuo Ishiguro's "Never Let Me Go," a beautiful novel that's best read unspoiled but which, to speak as vaguely as possible, could be called an increasing series of bets against death. The characters in "Never Let Me Go," like those in "The Midnight Club," keep thinking something is going to save them from the inevitable: Maybe it's faith, art, or love. But the truth is that nothing earns you eternal life, and if it did — see Flanagan's own "Midnight Mass" — it would be absolutely awful.

What Flanagan seems to be saying is that while fighting about unknowable things is petty, asking the questions is why we're here. And given the show's popularity, it's possible we'll get answers to all our questions before we're through.