Wild Stories From Ninja Films That Are Actually True

Whether you consider ninja movies a guilty pleasure or the apotheosis of modern cinema, there's no denying that the screen exploits of shadow warriors have an appeal that has endured long past their '80s heyday. For a significant portion of that decade, ninjas were popular action standbys in movie theaters and on home video, elevating such performers as Sho Kosugi and Michael Dudikoff to a position that at times, rivaled established Hollywood tough guys like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, and Chuck Norris.

While movie ninjas never quite achieved the same staying power — their stars waned as the '80s came to a close — their exploits remain well-loved by fans and film scholars alike, earning loving spoofs and tributes ranging from "The Lego Ninjago Movie" to the homemade excesses of "Ninja Badass."

Like many film subgenres rooted in low-budget and/or independent moviemaking, ninja movies have a complex mythology associated with them. A review of their history uncovers weird genre hybrids, eccentric filmmakers and actors, a few real-life martial artists, and Hollywood hopefuls who produced their own unusual, original takes on the ninja template. Below is a list of their exploits and excesses, and a deep dive into wild stories from ninja movies that, amazingly enough, are as undeniable as a nunchuk to the face.

Ninja movies predated the 1980s and came from many countries

For most people, the term "ninja" summons up a disjointed collection of pop culture references: the long-running Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise, of course, and Chris Farley's pratfalls in "Beverly Hills Ninja," just to mention a few. Cult movie fans might remember a series of seemingly interchangeable action movies from the 1980s, featuring a mix of Caucasian and Asian actors tossing spikes or stars (shuriken) at bad guys.

But movies about ninja or shinobi — the terms are essentially interchangeable, and are both singular and plural — predated the '80s boom by more than a half-century. Japanese filmmakers began making movies about spies or mercenaries trained in ninjutsu (an array of covert skills) in the silent era. Many of these early titles concerned ninja from folk tales or fiction like Jiraiya and Sarutobi Sasuke (and yes, they inspired the "Naruto" characters). However, very few of these silent efforts still exist, though 20 eye-popping minutes of "Jiraiya the Brave" from 1921 (believed by some to be the oldest surviving ninja film) can be seen here.

Today, ninja are not exclusively Japanese or American figures. When ninja went worldwide in the 1980s, other countries made their own shinobi adventures, including Sweden ("Ninja Mission"), Argentina ("Explosive Brigade Against the Ninjas"), South Korea (the Hong Kong coproduction "Secret Ninja, Roaring Tiger") and India ("Commando"). Ninja movies also transcend genres, allowing for ninja anime ("Gatchaman," which became the U.S. animated series "Battle of the Planets"), giant monster movies ("The Magic Serpent"), comedies ("Ninja Busters," which was lensed in 1984 but unreleased until 2014) and even "adults-only" films ("Female Ninja: In Bed with the Enemy").

The '60s boom featured very different ninja

Ninjas were inescapable in Japanese movie theaters during the 1960s in the same way that they enjoyed a burst of popularity in the 1980s. However, these shinobi titles were very different from their brawny American cousins. The highly informative Vintage Ninja site breaks down this period into two distinct types: the first included fantasy-fueled efforts like "Ninja's Weapon" (1956) and "The Scroll's Secret" (1958), which featured ninja that were more like wizards, battling evil sorcerers and giant monsters with a mix of swordplay and spells.

There was even an animated ninja film during this period — 1959's "Shonen Sarutobi Sasuke," which again focused on the adventures of the titular proto-ninja and his fight against a lake demon (with key animation by Hayao Miyazaki's mentor, Yasuo Otsuka). Unlike many of its fellow fantasy ninja films, it saw a theatrical release in the United States, though the American version, called "Magic Boy," oddly enough removed any references to ninjas.

When the '60s boom hit its peak in the early half of the decade, ninja films were a world away from the '80s titles. These were typified by the eight-film "Shinobi No Mono" series (1962-1966): black-and-white jidaigeki or historical action-dramas fueled by a mix of political intrigue, energetic camerawork and bloody fight sequences. Some of the elements featured here carried over to the '80s films — most notably the ninja's superhuman stealth skills and array of unique weaponry — but "Shinobi No Mono" and films like the stark, psychologically driven "Samurai Spy" (1965) couldn't be more different than Michael Dudikoff stalking the neon streets of Los Angeles in the "American Ninja" series.

A real-life ninja trained actors for You Only Live Twice

For many Westerners, their first exposure to ninja came via the James Bond novel/film "You Only Live Twice." The story, which puts a dissolute Bond in Japan (where he learns ninjutsu to carry out the assassination of his nemesis, Blofeld) was released in 1964 and serialized as a newspaper comic strip from 1965 to 1966. However, the 1967 US/UK film adaptation, with Sean Connery as Bond, gave moviegoers outside of Japan their first glimpse of ninja, who Bond trains alongside before storming Blofeld's volcano hideout in the film's climax.

Two real-life martial artists, including one trained in ninjutsu, were hired by film company Eon Productions to lend authenticity to the ninja sequences. Judo champion Donn F. Draeger not only trained Connery in Jojutsu (stick fighting) and other fighting styles, but also served as his stunt double during filming in Japan. Draeger, who penned numerous influential books on Asian martial arts, had previously served as John Wayne's stunt double in the 1958 film "The Barbarian and the Geisha."

Serving as consultant to the film on all things ninja was Masaaki Hatsumi, recognized today as a grandmaster of the nine schools of martial arts associated with ninjutsu. Hatsumi, who also appeared in it as an aide to Tetsuro Tanba's tough Japanese spy, Tiger Tanaka, was taught by Toshitsugu Takamatsu, a legendary ninjutsu instructor also known as "the Mongolian Tiger." Hatsumi later used his training to found the Bujinkan martial arts dojo in Japan, where thousands travel each year to learn ninjutsu. He continued to work with students well into his ninth decade before passing leadership to actor Takumi Tsutsui in 2020.

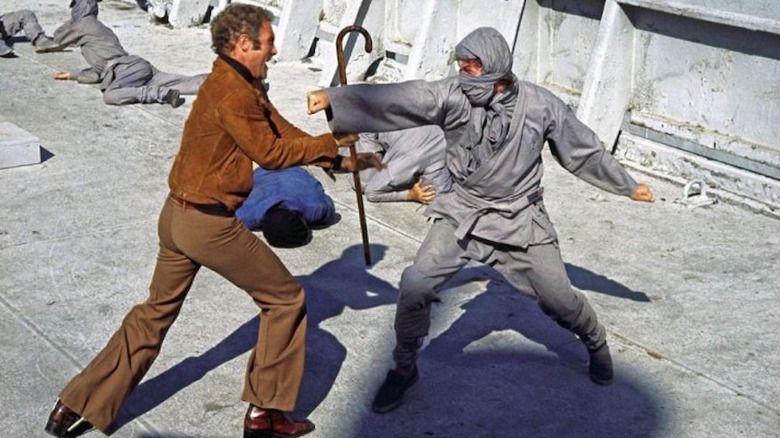

James Caan fought ninjas in The Killer Elite

By the 1970s, ninjas had infiltrated several levels of American popular culture. Actors like John Fujioka and Robert Ito played shinobi on "Hawaii Five-0" and "Kung Fu," while Marvel and DC introduced ninja characters in "Judomaster," "Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu" and the "Deadly Hands of Kung Fu" anthology. However, ninjas wouldn't turn up in a Hollywood movie until 1975, when James Caan and Burt Young — yes, Paulie from "Rocky" — teamed up to fight them in "The Killer Elite."

Directed by action auteur Sam Peckinpah, "Elite" concerns a pair of undercover agents for hire, played by Caan and Robert Duvall. Their testosterone-fueled friendship comes to an abrupt end when Duvall double-crosses Caan and leaves him for dead. Peckinpah leans hard into Caan's rehabilitation, which involves intensive martial arts training. This serves him well when he hits the revenge trail to stop Duvall from killing a Taiwanese politician (Mako). Caan thwarts the first attempt, carried out by a ninja played by real-life karate master (and inventor of the Kubotan key chain) Takayuki Kubota.

This doesn't sit well with Duvall, who summons a small army of ninjas to finish the job. However, in a scene that undoubtedly displeased hardcore martial arts fans, the shinobi are wiped out en mass by a machine gun wielded by Bo Hopkins. Peckinpah's ninjas are no more effective than standard issue henchmen, falling hard to a guy with a cane (Caan), dumpy Burt Young, and a middle-aged diplomat (Mako). However, Kubota gets a few moments to shine in hand-to-hand combat, as does Tiana Alexandra as Mako's daughter. A student of Bruce Lee and the wife of the film's screenwriter — Oscar winner Sterling Siliphant — Alexandra later became an award-winning documentarian.

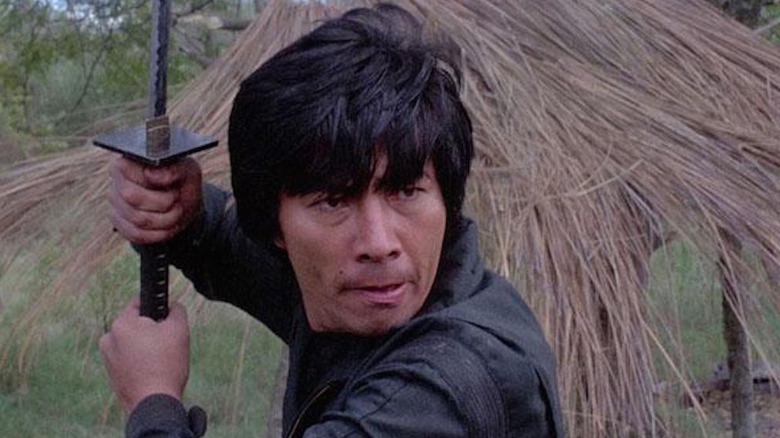

Mike Stone was supposed to be the first US ninja movie star

The ninja invasion of America was in full bloom in the early 1980s. As the martial arts culture compendium These Fists Break Bricks noted (via Collider), ninjas were on TV ("Shogun"), in books (the best-seller The Ninja,), and even in retail (Ninja perfume from Parfums de Coer). The time was right for a Hollywood ninja movie, and Mike Stone thought it would be his ticket to stardom.

Stone, a karate champion and instructor, pitched producers Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus on a ninja movie called "Dance of Death." The co-owners of The Cannon Group — the low-budget movie factory that produced many Chuck Norris action titles — launched production, hoping to beat 20th Century Fox's adaptation of Eric Van Lustbader's "The Ninja" to theaters, with Stone as both star and scriptwriter. They didn't need to worry — that production fell apart, despite having Irvin Kershner and John Carpenter attached as directors — but soon faced their own problems with what would become "Enter the Ninja."

Golan arrived on the "Ninja" set and cleaned house, firing the director, crew, and Stone as leading man. As Stone told The Cannon Film Guide Volume II, "In hindsight, there was no way I would ever be the leading man in any movie." Golan stepped in as director and hired Italian actor Franco Nero ("Django Unchained") to replace Stone. However, Golan also rehired Stone as fight coordinator and as Nero's stunt double, and allowed Stone to hire his own stuntmen, including a Japanese kendo and judo champ named Sho Kosugi, who also played the film's bad guy ninja. As it turned out, "Enter the Ninja" did mint a martial arts star: Kosugi, who became the face of ninjas in the 1980s.

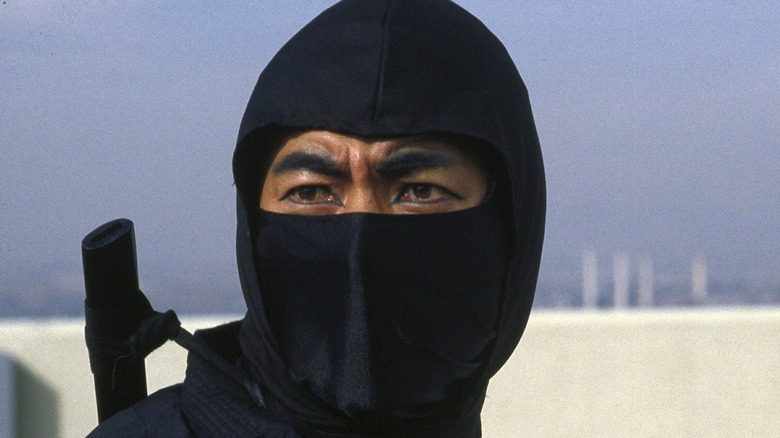

Sho Kosugi, the nice guy king of '80s ninja movies

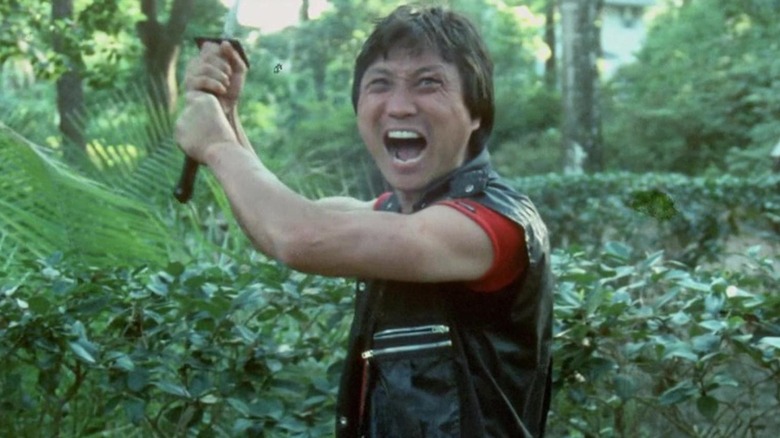

As the resident ninja in 1980s action movies, Sho Kosugi played a one-man murder machine that laid waste to any bad guy who dared to cross his path. By sword, by fist, or by shiruken, if you were on the wrong side of Sho Kosugi, your days were numbered. One of his most popular movies was titled "Pray for Death." That's the best you could hope for from Sho: that he'd kill you quickly.

That image seemed to contrast Kosugi's off-camera persona. A hard-working family man with a healthy skepticism about his status as an action hero, he told the New York Daily News in 1986, "I am not the greatest actor." That was true — Kosugi made Steven Seagal seem like an Actors Studio grad — but his screen persona made him not only exceptionally popular but also a groundbreaker: he was the first Japanese actor to top-bill an American action movie.

Kosugi was also nobody's fool. Elevated by Cannon from the bad guy in "Enter the Ninja" to hero in "Revenge of the Ninja," he was dismissive of the loopy "Ninja III: The Domination" ("It doesn't work," he told the Chicago Tribune in 1986) and ultimately left the company over a contract dispute. After "Pray for Death" (his first collaboration with Trans World Entertainment) earned an X rating, he requested cuts to ensure younger fans could see it ("So gross," he told the Chicago Tribune about a deleted scene in which his son and frequent co-star, Kane, got beat up).

When the box office take for ninjas cooled, Kosugi hosted the "Ninja Theater" VHS series and eventually returned to Japan, where he found new fame on television. In 2009, the Wachowskis paid tribute to his ninja days by casting him as the villain in "Ninja Assassin."

Michael Dudikoff wasn't quite ready to become the American Ninja

Though they'd lost their in-house ninja, Sho Kosugi, The Cannon Group saw that money was still being made in the shiruken and sword business, so they set out to launch a new ninja picture. As These Fist Break Bricks noted (via Collider), the company pre-sold "American Ninja" as a vehicle for Chuck Norris. The problem? Norris wasn't interested, so the studio set a casting net for a new action star.

Enter Michael Dudikoff, a former model-turned-actor who had amassed a resume of modest film and television roles playing affable boyfriends and best pals in movies like "Bachelor Party," and "Uncommon Valor." Director Sam Firstenberg was instantly smitten with Dudikoff, telling Kung Fu Magazine.com, "It was like, 'Who! This is the American Ninja!' The way he talked, the way he behaved, his body language, everything."

Unfortunately, what Dudikoff didn't have was American Ninja-level martial arts skills. He knew some Aikido and Judo, but wasn't entirely believable as someone who could fight multiple ninjas or jump out of a helicopter — as his character, Joe Armstrong, does in the film. As Firstenberg said, "He is not a martial artist in the sense that Sho Kosugi ... is." Thankfully, Cannon had Mike Stone on hand to choreograph the fights and help Dudikoff achieve ninja-level prowess. It certainly didn't hurt that he was paired on-screen with Steve James, a brawny real-life martial artist who lent credibility as Armstrong's partner.

Dudikoff would play Joe Armstrong in three sequels, sharing lead billing with actor David Bradley (not the "Harry Potter" actor) on "American Ninja 4." He then turned over the franchise to Bradley, who left the acting business soon after and maintains a low profile to this day.

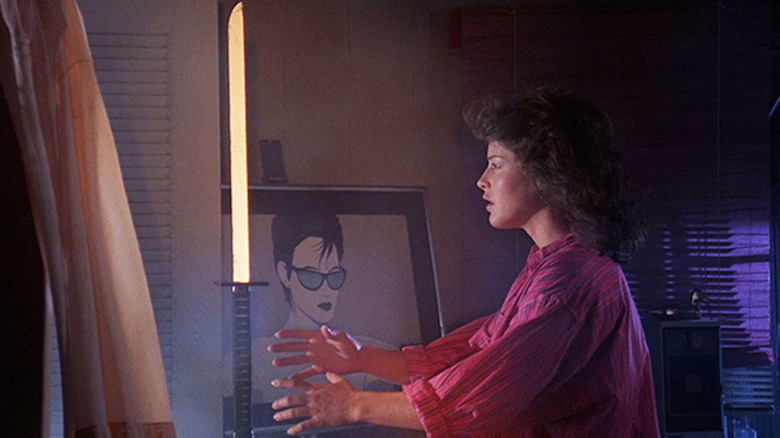

Check out some of the weirdest ninja hybrid movies

When a film subgenre runs out of gas, one of the most common ways for producers to retain fan interest is to fold elements of other genres into their titles. This cross-pollination has resulted in some inspired hybrids (see: "Colossal," "Bone Tomahawk") and some genuine oddities ("The Greasy Strangler," "The Apple"). Ninja movies are no exception. In fact, many of the earliest ninja films incorporated fantasy elements, like the aforementioned "Magic Serpent." This 1966 production from Toei — which was later the home of the "Power Rangers" franchise — features the folk hero Jiraiya and a parade of suitmation/puppet monsters, including a dragon, giant toad, and spider.

Ninja hybrids got exponentially weirder in the 1980s as demand for such movies reached a fever pitch. It was during this period that fans might have stumbled across such genre mutations as 1989's "Robot Ninja," an early no-budget comedy picture from horror filmmaker J.R. Bookwalter about a comic book artist who decides to fight crime as his robot ninja creation. "Ninja Academy," from the same year, applied the "Police Academy" template to a story about rival ninja schools populated not by lovable misfits but misanthropic weirdoes.

The hands-down winner for most bizarre ninja hybrid movie, however, has to be "Ninja III: The Domination." Though intended as the second sequel to Cannon's "Enter the Ninja," the film takes a wholly unexpected (and totally absurd) turn into supernatural territory. Lucinda Dickey — star of Cannon's "Breakin'" series — is an aerobics instructor possessed by the spirit of an evil ninja, which imbues her with assassination skills. James Hong turns up as an exorcist who fails to roust the ninja's spirit, which prompts — who else? — Sho Kosugi to step in. Floating swords, lycra bodysuits, laser eyebeams, and misuse of tomato juice all combine for a truly disorienting experience.

When a ninja movie isn't really a ninja movie

Let's say it's 1982, and you're an independent distributor with a sizable catalog of martial arts movies. Audiences aren't lining up for these titles like they used to — and definitely not like the new crop of ninja movies, cleaning up in theaters and on home video. So, being the enterprising type, you snip off the title cards from a handful of your movies and stitch on new ones that prominently feature ninja. The fact that your movies have little or nothing to do with ninjas, well, that's beside the point.

"The joke is you put the word 'ninja' in the title," Master Arts Video vice-president Rod Hurley said in a 1986 interview with the New York Daily News, "and you can sell a couple thousand extra copies."

Some of the more amusing examples of these retitled ninja movies are 1982's "Shaolin Prince," a Shaw Brothers production starring the great Ti Lung and directed by action coordinator Tang Chia. When it finally arrived on American VHS, it bore the title "Death Mask of the Ninja," despite the fact that no real ninja are featured in the film (however, it is still a terrific martial arts movie). Another Shaw Brothers' title, Lau Kar-Leung's excellent 1978 period action drama "Heroes of the East," does feature some ninjutsu, but it's not the main focus of the film, which concerns a face-off between Chinese and Japanese martial arts filtered through a broken marriage. Nevertheless, the Warner Bros. VHS bore the title "Shaolin Challenges Ninja" — one of several ninja-centric titles pasted on this film alone in the '80s, including "Challenge of the Ninja" and "Shaolin vs. Ninja."

The Franken-ninja movies of Godfrey Ho

While it's unlikely that the American-made ninja movies of the 1980s will ever be described as "classics," even the worst Cannon title looks Criterion Collection-worthy compared to the films of Hong Kong's Godfrey Ho, who flooded international markets with hundreds of cheaply made, nonsensical ninja movies during the 1980s and 1990s.

A former assistant director at Shaw Brothers, Ho formed his own production company, IFD Films & Arts, in Hong Kong. After cranking out Bruceploitation movies, Ho caught wind of Cannon's "Enter the Ninja" and enlisted his own Franco Nero — American actor Richard Harrison, a star of spaghetti Westerns — for his own ninja projects. Ho wasn't concerned that Harrison didn't know martial arts, or that the props and sets were dollar-store quality, and dialogue seemed composed of endless verbal loops about ninja empires. Ho simply hid his stunt players behind hoods and masks, then threw in enough smoke bombs and gunplay to hide the seams in an overzealous, eccentric re-editing process.

What set Ho's movies apart from other low-budget martial arts titles of the era was his practice of recycling footage from one film to create dozens of others. Scenes of Harrison in 1984's "Scorpion Thunderbolt" turned up in at least 10 other Ho titles; when that footage was exhausted, he began buying movies from other Asian markets and dissecting them for his own Frankenstein-like creations. Harrison later told the French cult website Nanarland that Ho's movies caused him to quit acting; quality — or lack thereof — didn't stop Ho, who moved on to kickboxing movies, stupefying genre mashups ("Robo Vampire" whips together "Robocop," Chinese hopping vampires, ghosts, and kung fu) and films with Cynthia Rothrock before apparently retiring in the early 2000s to become a film teacher, of all things.

Meet the Swedish ninja — yes, really

As mentioned before, ninja became one of the international languages of exploitation films in the 1980s. Ninjas wreaked low-budget havoc across screens in the Philippines ("Ninja's Force"), Hong Kong ("Ninja Over the Great Wall" with Bruce Lee imitator Bruce Le), and Turkey ("Holy Sword"/"Last Warrior," with burly Turkish action hero Cuneyt Arkin). Even India had its share of shinobi titles like "Commando," where past-his-prime leading man (and future politician) Mithun Chakraboty fights ninja terrorists led by ... a guy named Ninja.

One might not expect a ninja movie to come from Sweden, but the Scandinavian country did indeed produce a small handful of homegrown ninja titles in the late 1980s. The best known, at least to international audiences, is 1984's "The Ninja Mission," a hopelessly convoluted and astonishingly gory thriller that pits a CIA-backed team of Swedish ninjas against Soviet forces that hold a defecting Russian scientist hostage. Bo F. Munthe, the self-described "Grandfather of European Ninjutsu," co-stars as a member of the ninja team, whose martial arts skills could be charitably described as rudimentary. However, their ability to kill bad guys in as messy a manner as possible is top-notch.

Director Mats Helge Olssen, whom the Swedish Film Database describes as a "self-made filmmaker," made headlines in the early 1980s for helming and financing the historical epic "Sweden for the Swedes," which landed him in prison for accounting misdeeds after its costly failure. He rebounded with a massive windfall from international theatrical and VHS sales for "Ninja," which he followed with a slew of other action titles, each one as technically inept yet enthusiastically made as the next.

Miami Connection: the Citizen Kane of homemade ninja movies

The VHS boom of the 1980s wasn't just a fresh revenue source for recent theatrical releases and older titles. It also provided aspiring filmmakers a chance to get their homemade productions to a paying audience. These backyard auteurs typically focused on the genres that attracted the widest (and often least discerning) viewership: horror and action. If you owned a headband and a rubber throwing star, this was your chance to be in the ninja movie business.

Some of the best-known (or notorious) homegrown ninja titles included St. Louis detective-turned-director Ron White's $12,000 actioner "Justice, Ninja Style" and "L.A. Streetfighters" (with former Bruce Lee clone Jun Chong as a forty-something high schooler battling drug dealers). "Streetfighters" director Richard Park Woo-sang also oversaw another amateur ninja picture, "Miami Connection," that inexplicably found an audience three decades after its release.

Park saw an interview with taekwondo studio owner Master Y.K. Kim on a South Korean talk show and pitched him on making a martial arts movie. Kim recruited his students as cast members, borrowed money from friends, and even mortgaged his school to fund the picture. However, when he brought the film to distributors, they took one look at its plot — a mishmash of non-sequiturs about a rock band (composed of Kim and four grown men, all orphans) who run afoul of cocaine-dealing ninjas — and advised Kim to "just throw it away," as he told the Orlando Weekly.

Flash forward to 2009, when Alamo Drafthouse programmer Zach Carlson bought the film on eBay and screened a reel for audiences at their Austin, Texas location. Rapturous response led to festival dates, leaving Kim baffled, delighted and ready to make more movies. "[We have] planned to produce one top-quality action film with modern philosophy every three years," he told the Weekly.

The incredible 30-year odyssey of New York Ninja

Taiwanese actor John Liu earned a following for his superhuman high kicks in low-budget Hong Kong and Taiwanese kung fu movies during the 1970s, but as the old joke goes, what he really wanted to do was direct. So in the 1980s, he established his own production company and wrote, produced, directed, and starred in four near-incoherent, microbudgeted martial arts movies lensed in Paris and Mexico. The last of the quartet, "New York Ninja," began filming in 1984 but was abandoned after its distributor — the Golan-and-Globus-owned 21st Century Film Corporation — filed for bankruptcy. Liu gave up filmmaking and returned to Paris to oversee his own martial arts studio.

Flash-forward three decades, and the film preservation and home video distributor Vinegar Syndrome located the surviving elements — several reels of film, but no script or storyboards to follow. When Liu declined to complete his film, editor Kurtis M. Spieler painstakingly assembled the footage into a semi-coherent storyline, earning himself credit as the film's "re-director" in the process. After corralling cult actors like Don "The Dragon" Wilson, Linnea Quigley, and Michael Berryman to dub the actors, "New York Ninja" played the film festival circuit in 2021. It has since gone on to a national release and even screened on TCM.

As for the finished product? Well, seeing really is believing, though chances are you may not fully accept the sight of a ninja vigilante (Liu) who patrols New York City — occasionally on roller skates — in search of the cartoonish gang members who killed his wife. A radioactive villain, the Plutonium Man, and an army of grade school ninja fans also factor into the mix, which wobbles and bops to a new '80s-synth-style score by Voyag3r.

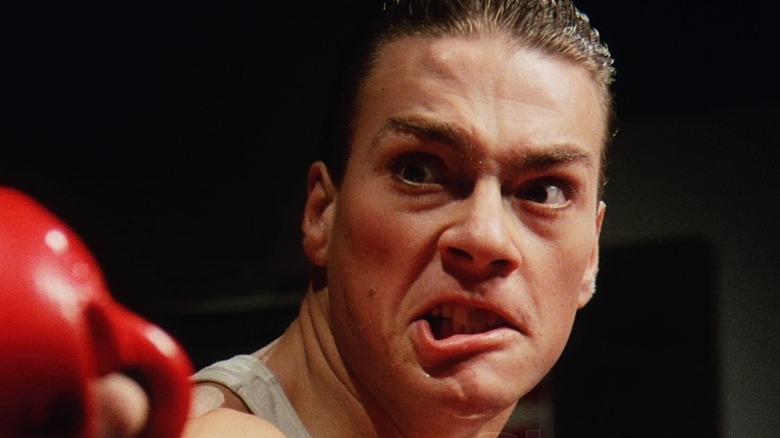

Jean-Claude Van Damme helped end the ninja movie's reign

Though ninjas appeared unstoppable on-screen, their appeal began to wane in the late 1980s. Ninja movies remained a popular draw on the home video market, and shinobi enjoyed continued appeal among very young consumers as the heroes of animated series like "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles." But theatrical returns for the Stateside king of the genre, Sho Kosugi, began to dwindle as the decade drew to a close. Adding to the downward trend in the fortunes of the ninja during this period was a wave of negative press that linked ninjas to real-life crime, including a highly-publicized 1984 home invasion of actress/director Penny Marshall's home by teenagers in ninja gear.

Profit-minded producers began shifting away from ninja by the end of the 1980s. Films like 1985's "No Retreat, No Surrender" and its lead villain, an energetic Belgian martial artist named Jean-Claude Van Damme, elevated the marquee status of kickboxing, a more aggressive combat sport with less mystical elements than ninjutsu. Kickboxing and mixed martial arts forms like shootfighting came to dominate the American action scene and elevated a host of new stars, ranging from Steven Seagal and Bruce Lee's son, Brandon, to direct-to-video players like Billy Blanks, Don "The Dragon" Wilson, and Cynthia Rothrock as martial arts movie heroes.

Ninja Badass spoofs and loves old school shinobi

Though ninja don't enjoy the same box office status as they did in the 1980s, the silent warriors remain a presence in feature films today. The "Ninja" films with Scott Adkins and the aforementioned "Ninja Assassin" put shinobi front and center in a modern action showcase, but ninjas have also turned up in everything from "The Wolverine" and "Snake Eyes" to "The Lego Ninjago Movie" and "Batman Ninja." From 2005 – 2011, the popular "Ask a Ninja" webseries minted one of the internet's early video stars.

For the most part, these were straightforward action or comedy titles, but two indie projects worked overtime to evoke the budget-minded brawling and absurd mythology of the '80s cycle. The YouTube/Blip series "Ninja the Mission Force" takes a page from the Godfrey Ho production playbook by dissecting various public domain films — everything from "Night of the Living Dead" to "The Boy in the Plastic Bubble" — and inserting footage from them into original (and deliberately awful) ninja-themed scenes to create surreal new films. Ninjas face off against dinosaurs, European spies, zombies, Italian spacemen and even Charles Bronson in the series' two seasons (to date).

While "Ninja the Mission Force" raises the bar for ninja parody (or lowers it, depending on your perspective), "Ninja Badass" gleefully vaults over it with a non-stop barrage of lowbrow visuals and gross-out humor. It's the singular vision of writer/co-producer/director/co-editor Ryan Harrison, who also stars as a Midwestern layabout with a colossal blonde mullet, spurred into action when a puppy-consuming ninja death cult kidnap the object of his affection. Harrison undergoes rigorous training by the portly "best ninja in Indiana" before undertaking his mission (which boils down to "save hot babes"). Deliberately silly and soaked in gallons of fake gore, "Ninja Badass" manages to pay educated homage while poking good-natured fun at old school B-ninja fare.