Things Only Adults Notice In Oliver And Company

"Oliver and Company" came at the tail end of a dark time for Disney. The documentary "Waking Sleeping Beauty" shows how the studio floundered in the decades since Walt Disney's death. New animated movies went from a regular event to an occasional drop-in, and rarely turned a significant profit. The studio took on new management in the form of Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg to right the ship. At first, it seemed like things would only get worse when their first project, "The Black Cauldron," bombed. Then things began to turn around with "The Great Mouse Detective," so it was only natural for Disney to follow up the story of Sherlock Holmes as a mouse with another animal-oriented adaptation of 19th-century literature.

It's easy to imagine the possibilities — "The Badgers Karamazov?" "Pandas and Prejudice?" Instead, Disney went with a loose adaptation of Charles Dickens' "Oliver Twist" in modern-day New York, with Oliver as a kitten and the gang of pickpockets as stray dogs helping Fagin pay off his debts to Sykes. It all led to success for Disney, to the tune of over $50 million (via Box Office Mojo). "Who Framed Roger Rabbit?" had revitalized both the company and the whole medium earlier that year, and the blockbuster success of "The Little Mermaid" and the '90s renaissance were just around the corner.

But most of us saw "Oliver and Company" as kids, when we couldn't care less about its literary or historical background. We probably missed a lot of other things, too. Here's a sampling.

The all-star cast

Nowadays, we take it for granted that an animated movie will sell itself on star power just as much as any other movie, but that wasn't the case in 1988. A-list casts were the exception, not the rule. Professional voice talent usually played the stars, with character actors, B-listers, and musicians mostly filling in supporting roles.

As Lindsay Ellis pointed out in "How 'Aladdin' Changed Animation (by Screwing Over Robin Williams)," "Oliver and Company" was an early step towards our current "Dwayne Johnson as Superdog" landscape. Bette Midler had been a reliable record seller and box office draw at the movies and on Broadway for decades before she played Georgette the poodle. For Fagin, Disney poached variety-TV staple Dom DeLuise from their biggest rival, Don Bluth, who had cast him in both "The Secret of NIMH" and "An American Tail." Before he played Tito the Chihuahua, Cheech Marin was already a huge star for his work with Tommy Chong, whose bandana Tito seems to have borrowed. And for a menacing mob boss like Sykes, you could do a lot worse than "Scarface" star Robert Loggia.

The biggest draw was Billy Joel as Dodger. He'd already been a steady hitmaker for nearly 20 years, with singles including "Piano Man" and "Uptown Girl," and his signature song "We Didn't Start the Fire" was still in his immediate future. So, it's only natural he gets a big musical number right out of the gate with "Why Should I Worry?" which winks at Joel's persona when Dodger picks up his trademark shades and briefly becomes the Piano Dog.

The all-star soundtrack

Billy Joel and Bette Midler aren't the only big-name musical talents onboard for "Oliver and Company." The movie opens with "Once Upon a Time in New York City" by Huey Louis and the News, famous for mega-hits like "The Power of Love," "Hip to Be Square," and "Stuck With You." Of course, now they're mainly infamous for the scene in "American Psycho" where Christian Bale sings their praises before jamming an ax into Jared Leto's skull.

Ruth Pointer of the Ponter Singers had done at least as much to define the sound of the decade before she dubbed Rita's singing voice for "Streets of Gold." She came to the role off a string of era-defining hits, including "I'm So Excited," "Jump (for My Love)," and "Neutron Dance." For whatever reason, Disney cast another singer as Rita's speaking voice. Sheryl Lee Ralph might not have quite had Pointer's superstar status, but she was still accomplished in her own right, with credits including the original production of "Dreamgirls."

There was plenty of star power on the composition end, too. Howard Ashman was fresh off the Broadway success of "Little Shop of Horrors" when he co-wrote "Once Upon a Time in New York City," and he'd soon be just as responsible as anyone for Disney's resurgence with his classic lyrics for "The Little Mermaid," "Beauty and the Beast," and "Aladdin."

Midler's solo "Perfect Isn't Easy" was co-written by Barry Manilow. The songwriter made a fortune on ad jingles and collaborated with Midler on her first two studio albums before launching his solo career, which included hits (if not critical favorites) like "Copacabana" and "I Write the Songs" (via People).

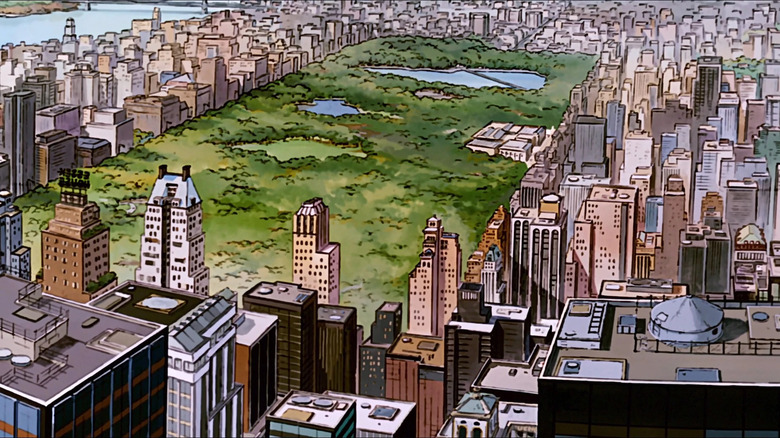

The New York landmarks

Disney World isn't just a theme park: It's a useful description of the environment most of the studio's movies take place in, a magical dreamland that's difficult to tie to any real time or place, where people may suffer occasionally but at least they and their surroundings stay clean and beautiful. "Oliver and Company" is a rare departure, anchoring the action in a surprisingly realistic time capsule of late-'80s New York City. The movie announces its intentions early, opening with an aerial shot of Manhattan Island.

The rest of the movie focuses on major landmarks that non-local kids probably missed. In the next shot, the "camera" pulls in for a closer look at the city, specifically Times Square, which gets the honor of hosting the title card. A later establishing shot gives us a good look at Central Park.

The opening lyrics to "Why Should I Worry?" are practically a tourist guidebook: "One minute, I'm in Central Park/Then I'm down on Delancey Street/Said, from the Bowery to St. Mark's." The skyline is always hanging around somewhere and, poignantly, puts a special focus on the now-destroyed Twin Towers. The significance of Oliver's new address on 5th Avenue should already be clear before the strays realize their new friend is rich, since the street has become synonymous with luxury homes and boutiques.

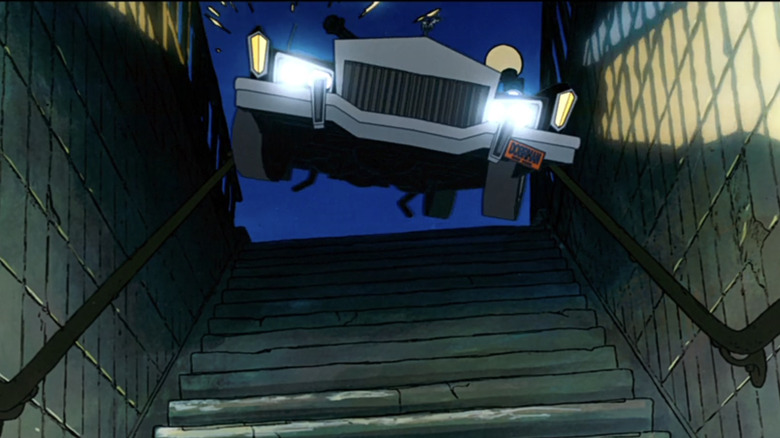

And, of course, the climax makes full use of New York's pioneering subway system as Sykes chases the scooter-driving heroes down the stairway, through the white-bricked station, and into the tunnels before fatally emerging onto the Brooklyn Bridge.

The early computer animation

Over 30 years after "Oliver and Company," CGI is now the dominant form of animation. But in 1988, the technology was still in its infancy. Pixar had just had its first big hit with the short film "Tin Toy," and "The Great Mouse Detective" had been hailed for its groundbreaking computer-assisted climax, even if the graphics were so primitive they had to be traced and filled in by hand.

If "Detective" made a big splash for one CG sequence, "Oliver and Company" is packed full of them. Even without inside knowledge of the production, a savvy adult viewer should notice that some scenes are jarringly more three-dimensional than others — especially for hard-to-draw objects like cars and buildings. Syke's car, in particular, is an obvious relic of the spiky, blocky style of CGI in the "Money for Nothing" era.

These technological experiments also allowed the animators to move more easily in three dimensions for scenes like Georgette's winding walk down the stairs during "Perfect Isn't Easy" and the climactic subway chase. It can be difficult to pin down just what makes these scenes so obviously digitized, but if you need proof, animator Tina Price has uploaded some of the movie's "wireframe" CG models.

It's also possible the animators didn't rely solely on simulations to trace their animated New York City. A contemporary review from the Minneapolis Star Tribune mentions that director George Scribner reused a technique from the production of "Lady and the Tramp" by shooting live-action footage on a dog-sized tripod to get a stray's-eye view of the city.

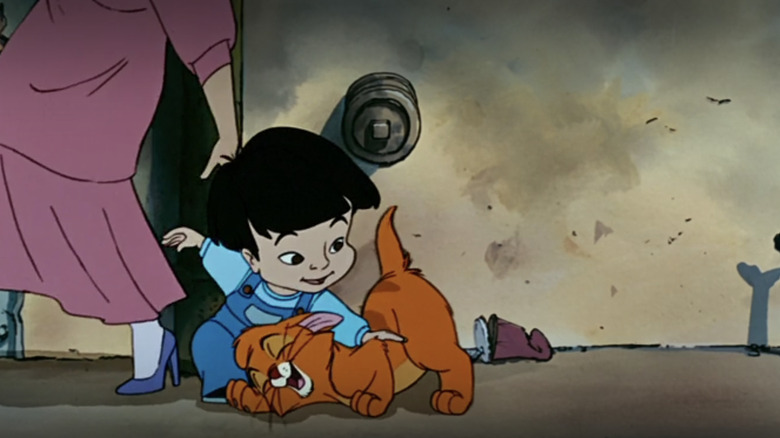

Oliver and Tito's inconsistent size

Disney was still a ways off from its glory years during the making of "Oliver and Company" as far as production value went, and that's especially obvious from its protagonist's sloppy scaling. It starts early, too: Oliver is introduced with a litter of other unwanted kittens in a cardboard box, and they're all small enough for passers-by to hold in their hands. Then as soon as he gets rained out and starts taking the search for a home into his own hands, he suddenly comes up to the human characters' knees when he sits on his hind legs. He's not even done with his growth spurt yet — soon he meets a toddler who's the same size he is!

"Oliver and Company" rarely gets that blatantly inconsistent again, but it doesn't exactly get better, either. Oliver can't even stay the same size relative to any given character! Sometimes he fits in the palm of Fagin's hand, but when he sits on his master's lap, he's suddenly about the size of his head.

Tito doesn't fare much better. When he's jockeying with his bulldog housemate Francis for control of the TV, he raises himself up to about half Francis' size. But later, he's small enough to use Francis' jowl as a mattress. And then he grows again when he's dancing with Georgette and they're somehow almost the same size.

The references to past Disney movies

After their decades-long string of flops, Disney was mostly coasting on nostalgia for their glory days. Then as now, they knew how to work that to their advantage, even if the references were much more subtle and inside than something like the 2022 "Pinocchio" remake. After all, there's a reason these callbacks are on this list and not "Things Literally Everybody Noticed in 'Oliver and Company.'"

The Easter eggs kick in before we're even five minutes in, when the crowds walking the streets of New York include a tall, lanky character who suspiciously resembles Roger, the owner of protagonist Pongo in "101 Dalmatians." Pongo himself appears as one of the dogs caught up in Dodger's performance of "Why Should I Worry?" — heavily redesigned to fit into Oliver's world, but still recognizable from his trademark red collar. There's a more definite series of cameos in the same scene, with a shot of Jock, Trusty, and Peg, the torch-singer dog played by real-life torch singer Peggy Lee, all from "Lady and the Tramp."

Meanwhile, have your fingers ready on the pause button when Georgette shows off all the photos she's received from admirers, including Tramp and Ratigan, the Vincent Price-voiced villain of "The Great Mouse Detective." Fagin's bedtime story for the dogs is about a rabbit named Bumper, obviously a reference to "Bambi" bunny Thumper.

Tito gets into the act towards the end. After refusing to "hotwire" Sykes' pulley to rescue Jenny because he's already been electrocuted twice, a little coaxing from Georgette gets him in such a good mood he sings the Seven Dwarfs' favorite song, "Heigh Ho," on his way to the control panel.

Dogs based on national stereotypes

The "casting" of the dogs in Fagin's gang will be lost on most kids. The Ruben Blades-loving, Cheech Marin-voiced Tito is a Chihuahua. The miniature dog breed is named after its birthplace in the Mexican state of Chihuahua — which has become so associated with the little yappy critters it can get hard to take older references to the district seriously (see the tragic sex worker Chihuahua in the Western classic, "My Darling Clementine"). Chihuahuas have only become more associated with Mexican culture (or extremely broad definitions of "Mexican culture") since "Oliver and Company" premiered, thanks to the inescapable "Yo quiero Taco Bell" ad campaign.

As for Tito's contentious buddy Francis, his bulldog status says at least as much about his character. The breed has been a longtime symbol of Great Britain, dating, according to The Great British Mag, all the way back to the 1700s. The article goes on to associate the bulldog with Britain's most famous personification, John Bull, who was often portrayed with the jowly hound. The name "British Bulldog" later attached itself to PM Winston Churchill during World War II, and then the wrestling tag team of Davey Boy Smith and the Dynamite Kid. All that fits Francis well, with his love of Shakespeare, aristocratic attitude, and severely enunciated accent — seamlessly faked by actor Roscoe Lee Browne.

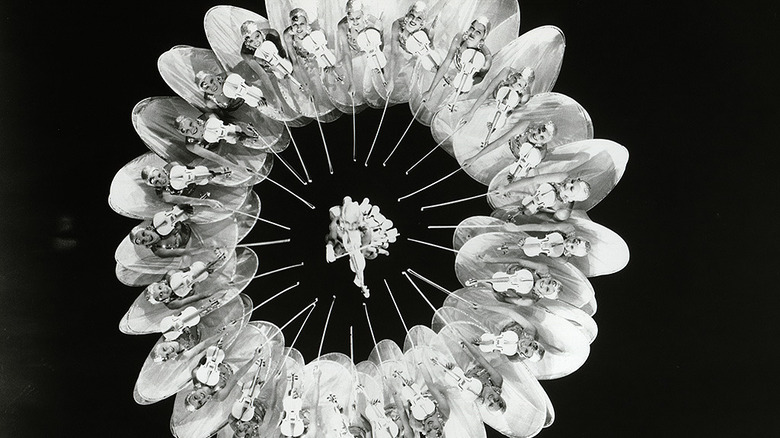

The Busby Berkeley reference

Disney's reference pool isn't limited to their own back catalog. During Bette Midler's big showpiece, she's accompanied by a flock of bluebirds who, in one of the movie's most memorable shots, form a halo around her head.

The classic live-action musicals couldn't exactly choreograph wild animals, but the scene is still an unmistakable tribute to Old Hollywood's premiere choreographer. Providing musical sequences to Depression-era classics like "Dames" and the "Gold Diggers" series, Berkeley set himself above his peers in the infancy of the movie musical by using the camera to do things that would be impossible on stage. One of his favorite tricks was to use bird's-eye views to arrange his dancers into geometric shapes, much like the birds in "Oliver."

While Berkeley began his career directing nothing but musical sequences and letting other filmmakers do everything else, he eventually graduated into the director's chair himself by the end of the '30s, creating a whole new string of classics, including the Judy Garland/Mickey Rooney team-up "Babes in Arms," while he followed his experimental instincts to even stranger places.

With all that pedigree, it shouldn't be a surprise Disney returned to the Berkeley well again for the "Be Our Guest" sequence in "Beauty and the Beast," this time living up to their predecessor's finest work. The sequence also includes Disney's most overt tribute to the master, recreating the famous synchronized dive and water ballet from "Bathing Beauty" with forks and a punchbowl.

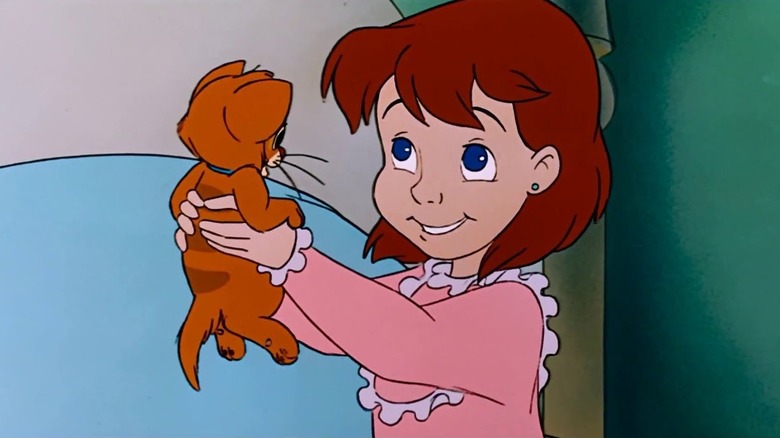

Oliver doesn't have a name until Jenny gives him one

It's easy to miss since his name's right there in the title, but Oliver stays anonymous for the first half of "Oliver and Company." He only receives his Dickensian name after Jenny adopts him, engraving it on the license tag with an address on 5th Avenue that inspires Fagin's ransom plot.

You'd think such a major gap would be hard to miss, but the script by Jim Cox, Tim Disney, and future blockbuster director James Mangold handles it remarkably gracefully. Oliver gets so many descriptive name substitutes that it's easy to miss he doesn't actually have one — "the kid" to Dodger, "the kitten" to Fagin, plus the always reliable indefinite pronoun.

Making Jenny the source of Oliver's name also serves some important narrative purposes. It's an elegant shorthand for the closeness of their relationship, and it shows Jenny's house is Oliver's home in a way that Fagin's derelict tugboat never could be.

The fine art references

When the strays break into Jenny's house to "rescue" Oliver, Francis can't help but be distracted by her parents' art collection. He's especially excited to see the works of Chagall and Matisse. Those names may not mean much to the target audience of "Oliver and Company," but they're still two of the most important artists of the 20th century. It would be impossible to cover all their accomplishments here, but the capsule biographies from "501 Great Artists" should be enough to fill in the gaps for everyone who studied something other than art in school.

The Parisian Henri Matisse was almost as influential as Picasso in popularizing the heavily stylized and sometimes totally abstract style that defined the century, and his simple forms and bold colors were at least as influential on popular art as his peers. Critics dismissed Matisse and his circle's work as "savage," nicknaming them the "Fauves" (wild beasts), a title the artists happily claimed. Matisse's art become even more boldly abstract as he aged. When an injury left him unable to stand at his easel, he adopted the paper-cutout technique that led to his most famous work.

Marc Chagall was a Russian-Jewish-French artist who stood in between the defining styles of his time, expressionism and surrealism, to create paintings more vividly dreamlike than either school could produce on its own. In fact, many of his paintings were based on his dreams and spiritual visions. He explored several recurring motifs in his deeply distinctive artwork — floating figures, flying fish, and the shtetl of his childhood.

Georgette is poisoning herself

Jenny loves her pets, but to make a Shakespearean reference that would surely please Francis, she loves them "not wisely, but too well." Chocolate can be poisonous to both cats and dogs, with symptoms including tremors, heart arrhythmia, vomiting, and diarrhea that can be fatal in large doses (via Pet Health Network).

Neither the writers nor Jenny seem to have known any of this. Jenny celebrates Oliver's adoption by preparing him an elaborate meal, including a pile of Cocoa Krispies cereal. Given how tiny Oliver is (depending on the scene), this could easily be enough to make him sick. There's no ambiguity as far as Georgette is concerned. Before the strays invade her room, we see her lounging on the couch with an empty box of chocolates. Despite what Forrest Gump's mama said, we know exactly what Georgette would get from that box of chocolates in real life — and none of it's pretty.

Fagin walks in on a murder plot

There are plenty of cute animal antics in "Oliver and Company," but in other ways, it's as dark a movie as Disney ever made. Departing from the long ago and far away of the studio's fairy tale adaptations and the more recent, nostalgic past of movies like "Mary Poppins" and "Lady and the Tramp," "Oliver and Company" drops viewers into New York City near the height of its poverty and violent crime.

Representing the "violent crime" side of the equation is Sykes, whose threats to murder Fagin and even little Jenny are all too sincere. While the legal status of Sykes' "business" is left open-ended for most of the movie, one scene that kids could easily miss (probably for the best) makes it clear we're dealing with the nastiest kind of old-school mafioso.

When Fagin calls on Sykes in his "offices" in an abandoned ship to propose his plan to ransom Oliver, he finds himself interrupting his creditor in the middle of a phone call. We only hear Sykes' end of it, but it's enough to put together that it's bad news for some poor sap who got on the mobster's bad side. The guy on the other end is obviously a professional killer, and Sykes takes a hands-on approach to his soldier's latest hit. He wants to make sure his victim suffers first, telling the hitman not to "kill him yet" but instead "start with the knuckles." By the time he gets to the murder method, the goofily anachronistic cement shoes are almost a relief from the kid-unfriendly violence the rest of the discussion implies.