Small Details You May Have Missed In The Babadook

This article contains discussions of child abuse.

Horror icons have been hard to come by this century. The genre's no longer the big business it was in the late '70s and '80s, when Hollywood was churning out Leatherfaces and Jason Voorheeses left and right. Now, most of the buzziest horror comes from small studios like A24, and every once in a while, an indie horror breaks into the mainstream and stamps itself on the collective consciousness.

With "The Babadook," director Jennifer Kent created a true horror icon and, thanks to a Netflix snafu, a gay icon. The Babadook monster combines the scariest bits of every horror villain, from Dr. Caligari to Freddy Krueger, and the monster's place in the popular imagination is even more impressive when you consider he barely appears onscreen. Plus, he never looks quite the same from scene to scene. Either way, the real horror comes from the everyday dread of Essie Davis as Amelia, a single mother whose husband tragically died on the way to the hospital to deliver their son, Samuel (Noah Wiseman). So there are two levels of horror in "The Babadook" — fantastic and realistic. There's plenty more where that came from. Let's take a look.

The Babadook is a movie unstuck in time

Maybe "The Babadook" became an instant classic because of its classic look. The Victorian home we're trapped in for most of the second half looks like it could have belonged to Dr. Frankenstein. There's nothing to date the film to its 2013 release, and if you try to date it all, you'll probably drive yourself up the wall with all the conflicting evidence. For example: Samuel watches a DVD on an '80s or '90s tube TV, Amelia drives a 1982 Peugeot, and all their books seem to have been printed sometime before World War II. Amelia also wears a white nightgown that could have belonged to one of Dracula's victims or the heroine on the cover of any paperback, Gothic romance. Even when we see her using a cell phone, it's an outdated Blackberry model.

There's order behind all this disorder. Jennifer Kent told Den of Geek, "I felt like, for a creature like [the Babadook] to exist, the world itself would have to allow it to happen. So I think if it was a naturalistic-looking world, and these things started happening, it would be quite ridiculous." She also goes on to suggest an in-story explanation for why Amelia hasn't upgraded any of her technology since her husband died, saying, "There are clues to a life that evaporated quite suddenly."

It's a black-and-white film in color

Jennifer Kent shows off an encyclopedic knowledge of horror in her interviews, and many of her film influences have one thing in common — they are done in black and white. From the German expressionists of the Silent Era, to the Universal Classic Monsters, to the B-movies of the '50s and '60s, many of the predecessors of "The Babadook" conjured nightmares without color. Kent even told Den of Geek, "Originally I wanted to film in black and white."

If she couldn't do that, she did the next best thing. Different rooms of the house are uniform blue or purple shades that fade into shades of gray. The floorboards, the bedframes, the sheets — all black and gray. That approach also extends to costuming. The cops trade their police blues for gray uniforms, and even a clown wears black. The daytime pallor and nighttime obscurity suggest the kind of post-production desaturation that's become the norm for Hollywood filmmaking. But Kent insists that she and her production designer, Alex Holmes, did it all on the set. She was meticulous about it, saying, "If we had a brown object in the frame, we got rid of it!"

You can see that attention to detail in the most seemingly insignificant scenes. When Amelia does the dishes, she uses a gray ball of steel wool, instead of a green sponge. It's not the kind of thing you'd notice on the first watch, but the detail would have stood out if Kent had done otherwise. If that had been the case, the carefully constructed world of "The Babadook" would have started to show cracks.

The Babadook becomes the Big Bad Wolf

If the Babadook has become an icon, it's at least in part because he draws from a long line of iconography that reaches back to a time before the birth of film itself. The most obvious inspiration is the Bogeyman — even before the Babadook's fateful book arrives on the shelf, Samuel insists on checking for the Bogeyman under the bed and in the wardrobe.

One of the non-cursed storybooks Amelia reads to Samuel suggests another folkloric godfather to the Babadook. We get a brief scene of Amelia reading the end of "The Three Little Pigs," where the wolf tries to sneak into the brick house through the chimney, but he ends up being cooked alive. The Babadook tries a similar trick, but with more success, in a chilling scene where his hat and coat fall into the fireplace.

We don't see Amelia and Samuel reading the rest of the story, but anyone who grew up reading the story can see the relevance of the wolf's refrain, "Little pig, little pig, let me in." The Babadook doesn't call Amelia a pig, but his demands to bet let in run throughout the film. And though he never "huffs and puffs and blows the house in," the wind effects in the final confrontation between Amelia and the Babadook suggest yet another connection.

The Babadook presents itself as a substitute father

"The Babadook" won the hearts of many who might normally shortchange the horror genre because, like most of the best horror films, it's not just about the scares. Most of us don't have experience with haunted houses, but many of us know more than we'd like to about grief, familial tension, depression, and mental illness. If the Babadook was a simple metaphor for any one of these things, the movie couldn't tell us anything we don't already know. But Jennifer Kent complicates her story by making the Babadook encompass a wide range of meanings, while also being a scary monster on the most literal level.

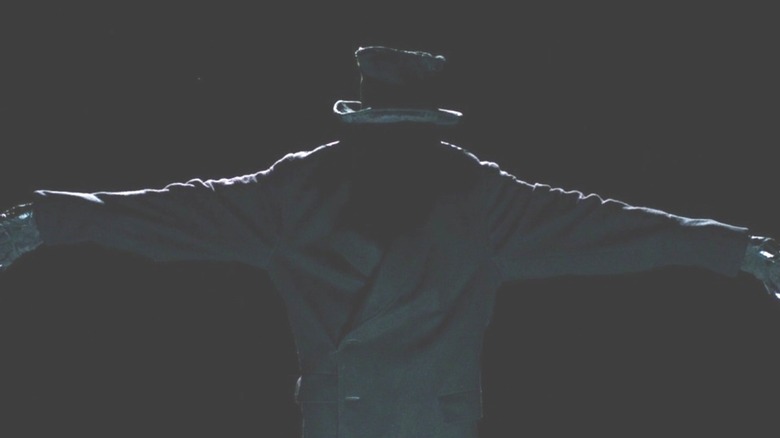

One of the Babadook's roles is a symbol of the loss, or more specifically absence, of Oskar, Samuel's father. There's a reason the monster manifests both in and as darkness, and it's not just because the dark is scary — it's to represent the absence of light, of anything visible. With an absent father and a stretched-thin mother, Samuel looks for guidance elsewhere, like his magic instruction DVDs. It's fair to suspect a connection between the two when the Babadook appears in a magician's top hat and long coat. Later on, the Babadook's role as a replacement for Oskar becomes even more obvious when he appears as Oskar himself, nearly convincing Amelia he's the real deal. With all that in mind, the Babadook's final fate is only appropriate — he ends up locked in the basement, along with everything else Oskar left behind.

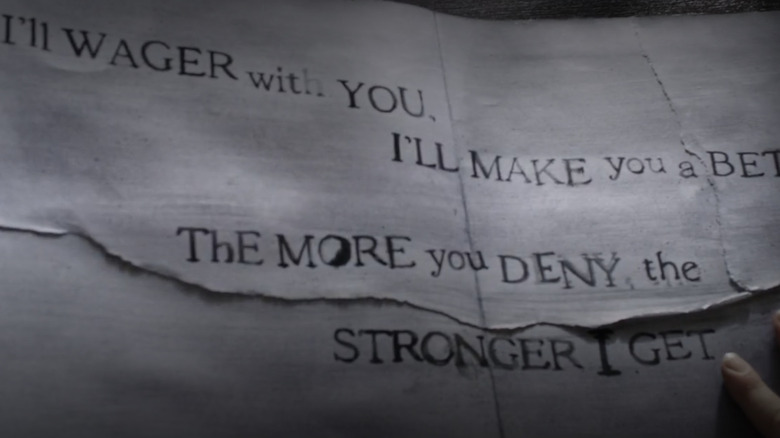

The Babadook is created by denial

If the Babadook is powered by grief, he's strengthened by denial. As Jennifer Kent explains, "For me, what was horrific was what had happened to this woman. And the fact that she couldn't face it was her greatest terror." Kent develops that idea throughout the film. Before she alienates her friends and neighbors, Amelia tries to steer every conversation away from Oskar. She all but literally buries her memories of him by locking every remnant of their marriage in the basement, forbidding Samuel to go down there.

It's a classic coping mechanism, but Amelia fails to see how much more pain it's causing. Her denial may even be responsible for her contentious relationship with Samuel. He was born within hours of her greatest loss, and he's described by multiple characters as being "just like his father." Samuel is a living reminder of everything Amelia wants to forget.

The Babadook knows this, and he knows how to exploit it. When Amelia destroys the "Mister Babadook" book, it reappears on her doorstep with a new page saying, "The more you deny me, the stronger I get." In spite of the warning, Amelia denies the Babadook's existence for as long as she can. Even when Samuel prepares to fight the Babadook, Amelia tries repeatedly to convince him there's no such thing.

If denial makes the Babadook stronger, acceptance makes him weaker. Toward the end, Samuel must expel the monster from his possessed mother. When the Babadook returns, Amelia reduces it to nothing by looking right in his face and shouting him down.

The Babadook movements are as unnatural as he is

One of the greatest strengths of "The Babadook" is that the human drama is so compelling you could cut the Babadook entirely and still have a pretty great movie. Like "The Turn of the Screw" and "The Shining," "The Babadook" leaves the question of the supernatural's existence open. In many ways, the answer is irrelevant. The Babadook couldn't have wreaked so much havoc if part of it wasn't inside Amelia from the beginning, and if her home life was any more than a nudge away from a nightmare.

You can find evidence for either interpretation in the way the Babadook moves, which could only come from the depths of a fevered mind or something beyond the known universe altogether. Jennifer Kent exploits the terror of the uncanny — things that are almost, but not quite real — in her staging of the Babadook's rare, on-screen appearances. There's something indefinably wrong about the way he moves. But, if you look closely enough, you can almost define it. It looks like frames are missing from the Bababook's scenes, as he jumps from place to place with eerie, choppy movements, like a puppet or an insect. The skittering on the soundtrack adds to the effect. He passes that trait on to Amelia when he possesses her, and her jerky movements are all the more fitting for a character who may be controlled by a puppeteer from the beyond.

The house turns into flesh when a crack opens in the wall

Amelia's anachronistic Victorian home exemplifies the influence of the Babadook, with the house appearing as distorted as its inhabitants. It's cliché to say a movie's setting is "like a character," but the house in "The Babadook" really does appear to be a living being.

At one point, Amelia peels the wallpaper behind the fridge and discovers a nest of cockroaches living in the wall. That would already be disturbing enough, but some subtle design choices push it into the realm of body horror. The wall behind the paper is the sickly, pinkish color of infected human flesh. With its irregular, rounded-off shape ringed by brown stains like the color of old blood, the hole looks more like a gash in a human body than a fault in dead stone. As if that wasn't disturbing enough, the shape of the hole is eerily vaginal as it seems to birth swarms of cockroaches.

The Babadook makes Amelia relive her worst moment

The Babadook can be a sadistic little freak, but some of his nastiest bits of psychological warfare are easy to miss. As you'd expect from a personification of trauma, the Babadook loves to twist the knife in Amelia's painful memories of Oskar's death. In an early flashback to the fatal car crash, Jennifer Kent puts special focus on the glass fragments that fly into the air as the window shatters. One of the first ways the Babadook announces his arrival is by hiding those glass shards in Amelia's soup.

Later on, the Babadook appears in the rearview mirror of Amelia's car, distracting her so much that she loses control of the wheel and drives right into oncoming traffic. Though nobody dies during this car accident, the backstory about Oskar makes it clear that the Babadook knows exactly what he's doing when he chooses to distract her while she's driving.

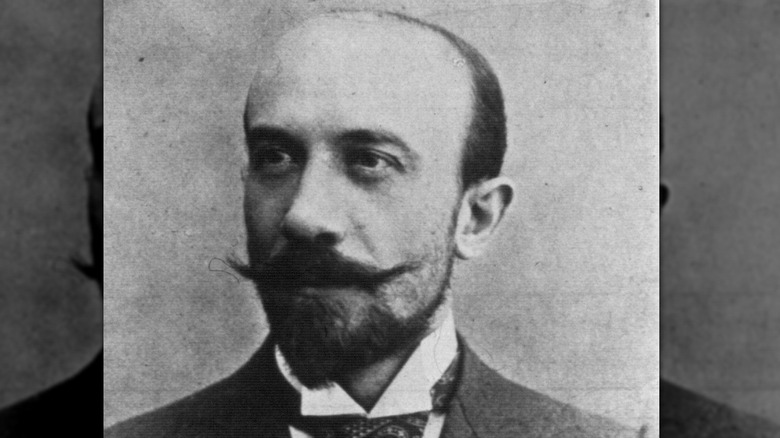

The TV offers a film history course

It's possible "The Babadook" has become such a hit with horror film fans because Jennifer Kent makes it abundantly clear she's a long-time fan, too. When Amelia watches TV, the most prominent and disturbing clips reach all the way back to the beginning of the horror genre. For example, Georges Méliès was a stage magician who became so entranced with the Lumiére Brothers and their early film experiments that he decided the real magic was in moviemaking. He spent 1896 to 1912 extending his illusionist act onto the screen, most famously in "A Trip to the Moon." A few years earlier, Martin Scorsese used Méliès' films as the epitome of movie magic in "Hugo." Kent uses the footage to a totally different effect, stripping away the delicate hand-painted colors to turn Méliès' work into stark black-and-white nightmares — and the appearances by Mr. B don't help any, either.

On the opposite end of the color spectrum, another scene draws from Mario Bava's lurid '60s horror anthology "Black Sabbath," specifically the segment, "A Drop of Water." The clip shows off some eye-poppingly stylized red and green lights and creeptastic makeup as a corpse rises out of her deathbed with unblinking eyes and a rictus grin. We get brief glimpses of other films with various levels of similarity to "The Babadook," like the Gothic noir "The Strange Love of Martha Ivers," the shoestring surreal horror of "Carnival of Souls," and the original, silent "Phantom of the Opera" with Lon Chaney.

The TV reflects the Babadook's unmasking

Some of the movie clips on the TV pay homage to Jennifer Kent's inspirations, but others offer more direct commentary on the plot. The "Mister Babadook" book warns, "I'll soon take off my funny disguise (Take heed of what you've read ... And once you see what's underneath ... YOU'RE GOING TO WISH YOU WERE DEAD."

That message seems ambiguous for most of the movie. Kent drops in red herrings to suggest that the Babadook is a purely external threat, or that the evil will come from Samuel, like your classic, creepy horror movie kid. The truth turns out to be even more disturbing. The Babadook's "funny disguise" is Amelia herself, and he becomes progressively more visible as he strengthens his hold on her.

Leading up to the climax, Amelia's already-frayed image as the loving mother slips off completely to reveal the abusive Babadook underneath. But before that can happen, we have another scene of Amelia drifting in and out of sleep in front of the TV. The images she sees are disturbingly symbolic: the Phantom of the Opera losing his mask to reveal the horrible "death's head" makeup Lon Chaney Sr. designed for the part, and a '30s animated adaptation of the wolf in sheep's clothing, adding a disturbing new layer of body horror as the wolf molds his face like clay before donning the sheepskin.

The possessed Amelia references The Shining

"The Babadook" parallels "The Shining" in many ways, including the themes of child abuse, and the way the fear is initiated by ambiguously supernatural forces. As we've seen, Jennifer Kent is not shy about wearing her influences on her sleeve, and that's exactly what she does in one skin-crawling scene.

The Babadook, now fully in control of Amelia, stalks Samuel to his room. First, she breaks the door down, screaming all the while, just like Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) in "The Shining." Once she gets inside, she goes into a full-on Nicholson impression that's based on the scene of Jack confronting his wife, Wendy (Shelley Duvall), on the stairwell. Amelia copies Jack's (and every grade-school bully's) move of throwing her victims' words back at them in a whiny voice. Her line "Sometimes I just wanna smash your head against a brick wall until your f***ing brains pop out" echoes Nicholson's line, "I'm not gonna hurt you ... I'm just gonna bash your brains in. Bash them right the f*** in!" right down to the over-enunciated tone and theatrical hand gestures. Both scenes end with the victim bashing the monster's head in and locking them up, but unlike Jack, the Babadook stays away.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

The Babadook turns into the ink of the book

The Babadook was able to torment the family with his repeated insistence for Amelia to "LET MET IN!" So of course, as Samuel says, the only way to defeat him is to "Let him out." If you've seen enough horror movies, you probably already know what that's going to look like — a nasty stream of black vomit. But in this, as in every scene, "The Babadook" has more going on than your average horror flick. The color is already significant — black as shorthand for evil is nothing new, but it's especially appropriate for the Babadook, with his all-black outfit and habit of hiding in the darkness. You may have also noticed the odd consistency of the vomit, it's much thinner than the real thing, almost like ink.

That's even more appropriate, because before he manifested in the flesh, the Babadook introduced himself as a book, A Bad Book. The ink Amelia vomits up is identical to the kind used in the old-fashioned, hand-printed book. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, and ink to ink — at least until the Babadook reveals he's not quite dead yet.

The Babadook disrupts the horror formula by following the fairy-tale formula

The average horror movie is based on a system of tension and release, like an emotional rollercoaster. "The Babadook" isn't. There's only one real kill in its entire runtime, and by then, it's almost over. Instead of whizzing up and down, Jennifer Kent lets the tension build without stopping.

The second incarnation of the "Mister Babadook" book lays out exactly what's supposed to happen in the end, with pop-up pages of Amelia first killing her dog, then Samuel, then herself. That premonition does a lot to keep viewers on edge as more and more pieces fall into place to bring that conclusion to fruition.

But in a shocking turn of events, Amelia and Samuel slay the beast and live happily ever after. The tension is released, but as a cathartic happy ending, not a cathartic scare. It seems like cheating for a horror movie, but that's not the genre "The Babadook" fits into best. Fairy tales weave throughout the film through Amelia and Samuel's storytimes, as well as the Babadook's own behavior. Really, it would be cheating to write a fairy tale without a happy ending.

However, it would also be cheating the heroes' mental struggles to make that happy ending too complete. The Babadook can never be totally destroyed, just tamed. And Amelia's last confrontation with the beast as she serves the Babadook his daily meal suggests that even that's a precarious truce.