Small Details You May Have Missed In 1992's Candyman

Candyman, Candyman, Candyman, Candyman ... well, let's leave off the fifth one just to be safe. Long before the success of movies like "The Babadook" and "Get Out" helped launch our current age of cerebral horror films (including Nia DaCosta's 2021 sequel), "Candyman" used the genre to explore themes of belief, class, gender, and racial prejudice without skimping on the scares. Transplanting "Hellraiser" creator Clive Barker's story "The Forbidden" from Liverpool to the Chicago Projects, director Bernard Rose told a story as full of big ideas as big shocks.

While researching a paper on urban myth, graduate student Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) becomes fascinated with the legend of the Candyman, the undead victim of a lynch mob who allegedly continues to haunt the city where he died. Before long, she gets pulled into his supernatural world almost as the Candyman frames her for his murders, cutting her off completely from her former life until she agrees to be his victim. There's a lot going on in "Candyman," and not all of it is obvious at first glance. Here are just a few of the secrets we've discovered in this film.

The opening translates the story's first words into pictures

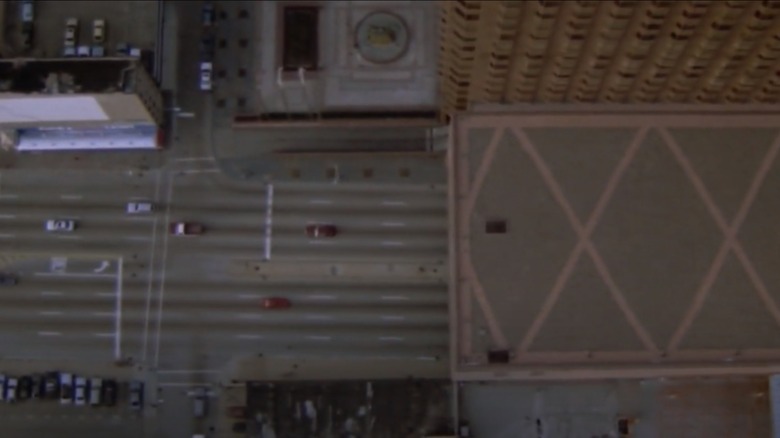

In many ways, "Candyman" is a fast and loose adaptation of "The Forbidden." In addition to moving the action across the Atlantic, Rose invents the Candyman's backstory (and the racial issues it raises) out of whole cloth, and he makes all the other changes necessary to expand a short story into a feature film. In other ways, though, the adaptation is painstakingly accurate, and one example of this comes right away as the opening credits roll over a bird's-eye view of the streets of Chicago. This unusual perspective makes the mathematically elegant structures underlying the city visible before we descend into the ugliness that's apparent from ground level.

As critic Matthew Dessem pointed out on Slate, this is an image that lines up nicely with Barker's words as he opens up "The Forbidden": "Like a flawless tragedy, the elegance of which structure is lost upon those suffering in it, the perfect geometry of the Spector Street Estate was visible only from the air." This God's-eye view adds an unsettling sense of paranoia to "Candyman." In death, the former Daniel Robitaille has become something far more than human. He calls himself a god and floats above Helen's gurney when she's committed. Could this be the "Candyman" version of the "killer cam" one might find in a more conventional horror movie?

Candyman is about segregation and exploitation from the first shot

Part of what makes "Candyman" so effectively haunting is Rose's understanding that the reality of white supremacy is scarier than any ghost story. That statement gets muddled — the movie can be said to play on white viewers' fear of Black men in Candyman and the gangsters who impersonate him. The story condemns the fears of interracial relationships that led to Candyman's lynching, but also exploits them in his pursuit of Helen. And while she pays the price for barging into Black spaces, she still becomes a white savior archetype — literally, if the messianic mural of her in the finale is anything to go by.

Rose may have his blindspots, but he did his homework just the same. Matthew Dessem further explores the significance of the opening shot. That's not just any street we're looking at — it's the Eisenhower Expressway, a disastrous civic project that Robert Loerzel reports bulldozed over the Near West Side, a lower-income neighborhood inhabited mostly by Black and immigrant families, 18,000 of whom lost their homes to construction (per WBEZ Chicago).

It's doubtful Rose expected anyone but a handful of amateur Chicago historians to pick up on the significance of this location, but a few scenes later, he lets the dialogue spell out just how much segregation and gentrification is on his mind. Helen discovers that her expensive condo was originally built as a housing project until the city realized, as she explains, "There was no barrier between here and the Gold Coast. Unlike over there where you've got the highway and the L train to keep the ghetto cut off." A whole neighborhood locked in poverty and cut off from the outside world — the perfect setting for an undead murderer to wreak havoc.

Candyman is a patchwork of real urban legends

No one ever actually believed in Candyman, though that may have changed after the movie premiered. You could be forgiven for thinking a genuine urban legend inspired the movie — Candyman has the feel of authenticity to him, in no small part because some of the most persistent urban legends are deep within his DNA. One that should be familiar to anyone who's ever had a slumber party is Bloody Mary. Jan Harold Brunvand describes the ritual of summoning some variation on Bloody Mary by saying her name in a mirror, with deadly results. Much like Candyman, there are conflicting reports of tragedy keeping this spirit from finding rest.

Candyman's lair features an even more pervasive legend, still reported as fact so often that it's inspired a meme and changed the whole shape of trick-or-treating: the razor in the candy bar. Some new tainted candy scare resurfaces every year. One of the most pervasive threats is razor blades, based on a rumor spread by two of America's most popular late-20th century advice columns, Ann Landers and Dear Abby.

The huge meathook the lynch mob jammed into Candyman's bloody stump connects him to another iconic urban legend: the Hook. In most versions of the story, a teenage couple are looking to make out in their car when news comes over the radio of an escaped mental patient with a hook for a hand. The girl gets spooked and insists on going home, and the boy resentfully agrees. When they arrive, they find the killer's bloodied hook on the car handle, torn off when they drove away. A moment later and they'd be dead. If only the Candyman were so easy to escape.

Sam Raimi's brother and stuntman-of-choice appears as the world's oldest teenager

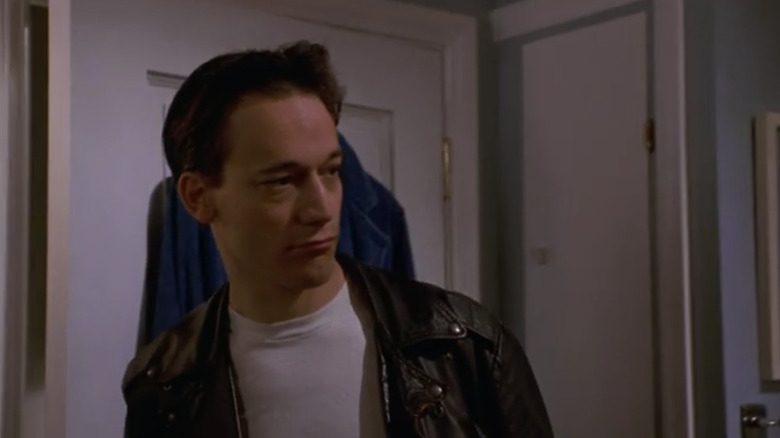

Before Helen digs into the persistence of Candyman legend in Cabrini-Green, she discovers the story by interviewing a college freshman. It's a classic story: A girl's alone babysitting, her crush shows up, carnage ensues. There's one small wrinkle, though — her "bad boy" partner has a distinctly receding hairline and tired eyes. It should surprise no one that the "teenager" in question was over 25, but his specific identity is a little more intriguing.

That's Ted Raimi, brother of Sam, the director of the "Evil Dead" and "Spider-Man" trilogies and "Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness," among others. And if Ted looks rough for his actual age, let alone his onscreen age, Sam's probably to blame. In true big-brother fashion, he's tormented Ted every chance he's gotten — and his filmmaking career has given him plenty of chances. Ted appears in "The Evil Dead" as a stuntman (i.e., guy who gets beat up) and in "Evil Dead 2" as the "hideous horror hag," spending most of his screentime in a lead-heavy suit hanging from wires in the heat of a brutal Southern summer. Somehow, their relationship survived, and the Raimis have continued working together, most notably with Ted's role as J. Jonah Jameson's assistant Hoffman in all three "Spider-Man" movies.

Trevor takes a whole lecture to belittle Helen's work

Helen is a classic resourceful horror heroine, which might make you wonder why she's been saddled with a cheating, condescending bore of a husband like Xander Berkley's Trevor. It takes most of the movie to reveal the depths of his awfulness when he dumps his intellectual peer for a student who won't mind being baby-talked to as soon as Helen's committed, but the hints are there from the moment he's introduced.

When we first meet Trevor, he's lecturing on urban legends, and he dismisses Helen's objections that he'd promised he'd wait until her graduate thesis was done before covering the same subject. Helen's objections seem more justified the closer you listen to Trevor's lecture. Helen is devoted to tracing the origins of urban legends and the true stories that inspired them, which eventually leads her to Candyman. Before she can present her findings in class, Trevor's already primed his students to dismiss them. He calls the classic story of the sewer gators a "delusion," and belittles them as "bedtime stories." It should already be apparent how tenuous the Lyles' marriage is if that's how little Trevor thinks of Helen's work.

Candyman created Cabrini-Green

Despite the far-fetched supernatural elements in "Candyman," the horror of Cabrini-Greene is all too real — if not, as Robin R. Means Coleman suggests in the book "Horror Noire," exaggerated by white anxieties. Time's Andrew R. Chow reports that the neighborhood had been nicknamed "Little Hell" as far back as the 19th century thanks to the heavy Mafia presence and industrial air pollution. The Cabrini-Green development was supposed to save the neighborhood, but the Chicago Housing Authority's mismanagement turned it into a crumbling wreck with unreliable utilities.

In the absence of other authorities, the gangs moved in, leading to a wave of murders, including the mirror-abetted murder of Ruthie Mae McCoy (via Chicago Reader), fictionalized in "Candyman" as Ruthie Jean. Chow includes stories from residents who remember Cabrini-Green as a welcoming, tight-knit community. But to the outside world, it seemed like a horror show that racism and neglect couldn't adequately explain. The neighborhood seemed to be cursed.

"Candyman" suggests that's exactly what it is. After murdering him, legend says, the lynch mob scattered Candyman's ashes over the future site of Cabrini-Green. The murders are directly linked to the ghost and his imitators, but Rose also suggests his remains cursed the earth into the living hell that Cabrini-Green became. And if that sounds like he's letting the white supremacist forces that kept its residents poor off the hook, it's worth remembering that Candyman didn't choose to curse the earth. That was the work of the mob that murdered him for daring to touch a white woman, making the supernatural explanation for Cabrini-Green a myth that reveals the truth.

Candyman's read his Shakespeare

In contrast to the barely-verbal killers of the average slasher film, Candyman is a remarkably cultured murderer. With Tony Todd's smooth voice and his bloodied but dapper Victorian dress, he's closer to the aristocratic villains of classics like "Dracula" and "The Phantom of the Opera." As the wealthy son of an ex-slave inventor and an artist mingling with the Chicago glitterati, it would be more surprising if Candyman didn't cut such a dashing figure. And if you don't share his expensive education, some of the signs of it might slip past you.

One of the remarkable things about "Candyman" is how it creates an iconography with a mythical power most horror franchises take multiple installments to develop: the hook, the mirror, the bees, and the mural/doorway of Candyman's monstrously huge mouth. There's also that ominously repeated message: "Sweets to the sweet." If that line's especially resonant, that's because it's even older than Candyman himself. In Shakespeare's "Hamlet," the tragic prince of Denmark discovers that his rejection of his fiancée Ophelia in his pretended madness has driven her to the real thing (accidentally killing her dad couldn't have helped either). When Hamlet returns from overseas, he meets a gravedigger and learns that Ophelia has drowned herself and they're sitting in her plot. When the funeral procession brings the body by, Hamlet's mother Gertrude scatters flowers into her coffin, saying, "Sweets to the sweet: farewell!"

Of course, modern viewers are more likely to associate "sweets" with candy than flowers, making it a perfect phrase for Candyman to steal.

Helen shares Candyman's fashion sense

It's an old cliché for a movie villain to tell the hero, "We're not so different, you and I." But in "Candyman," it's true. Of course, Candyman's appearance in the mirror suggests he's a reflection of Helen. Candyman frames her for his murders, but in a way, the other characters aren't wrong to believe she's responsible. She summons Candyman twice in the mirror. All the carnage of the second half stems from Candyman's anger that she's diminished the faith he needs to live by "debunking" his existence when she identifies the gangster who's taken his identity. In the end, she becomes his successor. Jacob, the little boy from Cabrini Green, even mistakes Helen for Candyman when she crawls through a bonfire with one of the killer's spare hooks to save the baby he's trapped inside.

There are subtler hints, too. We always see Candyman in the long fur overcoat he was murdered in. And we almost always see Helen in similar overcoats that she wears to keep out the bitter Windy City winter. If this were an insignificant or accidental connection, Rose probably wouldn't draw attention to it as much as he does. Helen leaves her overcoat behind to explore Candyman's lair, and we watch the whole process as her research partner Bernadette (Kasi Lemmons) folds it up and drapes it over the dirty bathtub before she's willing to sit on it. The overcoat comes into the foreground again as Helen leaves the police station after being accused of Bernadette's murder. Trevor protects her from the swarms of reporters massed outside by covering her head with the overcoat.

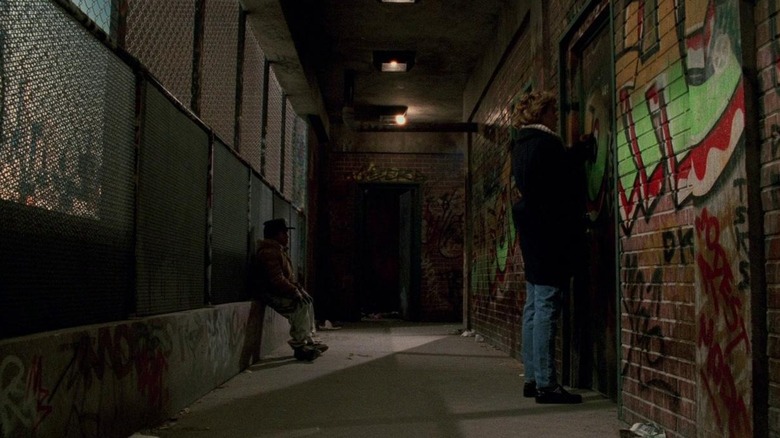

The camera symbolizes Helen's role as a tourist in Cabrini-Green

Like any good horror heroine, Helen is an innocent victim of unspeakable evil. But like any good tragic heroine, on some level, she brings it all on herself because of her own hubris. It's clear from the moment she decides to investigate Cabrini-Green that she doesn't belong there. While Bernadette is appropriately cautious about entering gang territory, where even the law-abiding citizens have good reason to be suspicious of upper-middle-class interlopers invading their space, Helen barrels ahead with unearned confidence, breaking into a murder scene and the secret spaces beyond. Vanessa Estelle Williams as Anne-Marie McCoy wearily sums up the type of dehumanization she's come to expect from outsiders: " What you gonna study? How we bad? We steal? We gang-bang? We all on drugs, right?"

In other words, Helen enters Cabrini-Green as a tourist, and Rose uses some clever visual shorthand to establish that fact. Like any Ugly American overseas, she can't resist snapping photos of everything in sight, to the point that it's hard to believe she doesn't run out of film until she finds Candyman's inner sanctum.

Trevor becomes Candyman

After Candyman deposits Helen at another of his crime scenes, there's no more bailing out for her. She gets committed to a mental hospital and, after she tries to break her restraints and screams at Candyman when no one else can see him, she's put on such a heavy regimen of sedatives she doesn't even realize a month has passed. Eventually, she escapes and hopes to find a safe haven in her condo. Instead, she walks in to discover Trevor's new girlfriend has moved in and taken over the place, slathering everything in Pepto-Bismol pink. When Trevor reappears fresh out of the bath, his outfit should look familiar to sharp-eyed viewers. His bathrobe looks even more like Candyman's fur coat than Helen's overcoats did, and he's got a white hand towel wrapped around his neck like Candyman's cravat.

There are multiple possible explanations for this. While Candyman represents the cycle of white men exploiting Black men, with his repeated demands for Helen to "be my victim," he has shades of the exploitation of women at men's hands as well. As he callously tosses Helen aside for a new lover he doesn't have to respect as a peer the minute she's hospitalized, Trevor steps into Candyman's role. Or it could suggest something even more sinister: The costume is an outward manifestation of Candyman's influence as Trevor makes Helen's home unsafe, leaving her no one to turn to but Candyman himself.

Candyman lives in a temple to himself

One of the most intriguing themes "Candyman" explores is the connection between urban legends and belief in general. After all, the ancient legends of gods and demigods grew out of religion. Could urban legends play a similar role? Candyman certainly seems to think so. He calls the people of Cabrini Green his "congregation" and fears that if they cease to believe in him, he will cease to exist. If that's the case, his murders take on the significance of sacrifices, especially in the ritualistic care he takes with Baby Anthony.

With that in mind, Candyman's inner sanctum becomes more than just a collection of spooky imagery. Instead, it reveals itself as a kind of run-down temple or cathedral. Candyman sleeps on a concrete block that resembles an altar. The room is filled with candles, much like a Catholic church or Buddhist temple. The walls of Cabrini-Green are covered in spray paint, but the more elaborate murals of Candyman's home suggest the fresco artwork of Roman temples and Renaissance cathedrals. Not that Candyman's short on spray paint, but their application on the windows gives them the appearance of stained glass.

You can see Virginia Madsen's eyes move when she plays dead

"Candyman" is a great movie, but by no means is it perfect. After all, even in the most professional production, little goofs can sneak through. The most obvious example comes near the end. Helen manages to escape Candyman and rescue Anne-Marie's baby from a bonfire, but once she's completed her mission, she dies from the burns. Rose then shows us Helen's funeral, and that's where a particularly noticeable error sneaks through.

While Virginia Madsen gives a great performance throughout the film as Helen, she doesn't quite seem to have mastered playing dead. She at least manages to keep her eyes closed, but look closely and you'll still be able to clearly see her eyelashes twitching. Of course, that little screw-up isn't enough to diminish such a classic horror film. After all, "Candyman," like Helen, can never really die.