The Ending Of Alice, Sweet Alice Explained

A matte plastic Halloween mask, a blur of a yellow raincoat, and the flash of a massive kitchen knife: This is "Alice, Sweet Alice." Alfred Sole's brutal 1976 flick pairs confrontational '70s grime with genre elements that went on to define the Hollywood slasher.

Set in 1961 in Paterson, New Jersey, "Alice, Sweet Alice" follows the Spages family. The father, Dom (Niles McMaster) isn't in the picture, leaving Catherine (Linda Miller) to raise their two young daughters: bubbly, spoiled Karen (Brooke Shields, in her first big screen appearance), and the bitter, pre-teen Alice (Paula E. Sheppard), who was born out of wedlock before Dom and Catherine were married. When Karen is brutally murdered at her First Communion, the powers that be reluctantly consider that the mentally unstable Alice may be a suspect. Several dead bodies later, the film reveals that Mrs. Tredoni — the priest's housekeeper — is the killer. And when her mask is dislodged during the murder of the Spages' landlord, a nosy detective catches her in the act, leading to the tension-filled final scene in which the police prepare for the arrest while Tredoni, and the rest of the community, attend Mass.

And so, "Alice, Sweet Alice" arrives at its shocking conclusion, with Mrs. Tredoni spilling more blood before the credits roll. The film's conclusion is striking for a number of reasons. It reinforces key themes, clarifies character arcs, and leaves us with a number of intriguing questions as we file out of the theater. So let's dig our nails into this incredible conclusion to one of horror's greatest slashers.

Consider yourself warned: the following contains in-depth spoilers for "Alice, Sweet Alice."

Father Tom doesn't know congregants as well as he thought

It's easy to peg "Alice, Sweet Alice," as an anti-Catholic treatise. And while the film is inarguably critical of the Church, Alfred Sole's religious-themed slasher isn't black-and-white in its fault-finding. Case in point: Father Tom, the spiritual leader of the Catholic community in Paterson. Charismatic and gentle, New Jersey-born actor Rudolph Willrich endows the priest with an incorruptible charm. He is, as far as we know, a genuinely good guy and a devoted leader. He lends Dom his car, he doesn't judge or shun the Spages for their pre-marital sex or divorce, and he attempts to keep Alice's school records private when the police come calling. You would expect a film with such a bone to pick with the Church to paint a priest into a scuzzy, corrupt corner. But Father Tom seems to be earnestly devoted to helping the believers in his care.

He's the kind of priest who prides himself on having interpersonal relationships with each and every one of his congregates. So, when Mrs. Tredoni's other shoe drops and the cops arrange a sting at Mass to arrest the old woman, Father Tom insists that he personally escort her to the cops when she comes to take communion. "She's too close to Catherine and Alice," Tom tells the detective, "there's no telling what she'll do." With pleading and confidence in his voice, Tom insists: "I know I can get her to come with Father Pat and me ... I can handle her, she wouldn't do anything to me." Famous last words. Not only does Mrs. Tredoni not come quietly ... she plunges her knife deep into Father Tom's throat. The priest's conviction now reads as arrogance: His knowledge of his flock has limits ... as does his gentle touch.

Mrs. Tredoni kills to punish congregants for their sins

Until the film's tension-filled conclusion, Mrs. Tredoni keeps her murderous ways hidden under a facade of duty to the Church. We, the audience, are let in on her warped worldview before the rest of the congregation. In the initial reveal that Mrs. Tredoni is the killer, she pounds on Dom's chest, denouncing Alice's father as a "filthy pig" and the girl's mother as a "whore." As she rolls Dom's bound and battered body towards the ledge of the rooftop, she mutters to herself that his death is God's will. Not long after, when Alice's mother, Catherine, arrives at Father Tom's house to ask about her missing husband, Mrs. Tredoni almost spills the beans. After cryptically suggesting that Catherine is worried that "God has sent St. Michael to take another of your loved ones," Mrs. Tredoni reveals that she believes God kills children to punish their parents.

Later, in the film's climactic communion scene, Mrs. Tredoni cuts to the heart of what ails her. When she's asked to come quietly, Mrs. Tredoni doesn't seem to register that she is under arrest, instead preoccupied with the fact that she has been denied communion. "But you give it to the whore!" Mrs. Tredoni screams, loud enough for the whole congregation to hear. It's an intensely revealing moment: Mrs. Tredoni does not see her murderous acts as sin. Catherine having a child out of wedlock, however — that's an offense punishable by multiple deaths.

Mrs. Tredoni's sexually-charged obsession with Father Tom becomes destructive

While it's easy to get lost in the shock of Mrs. Tredoni's killing spree, it's also clear that something a little less puritanical is behind her murderous impulses. Between the old woman's wild-eyed insistence that God has ordered Dom's death for his "horrible sin" of conceiving a child before getting married, if you listen closely, she also hisses that "Father" — meaning Father Tom — "belongs to the Church." Later, when Mrs. Tredoni makes coffee for Catherine who has come to see Father Tom, she lets it slip that it's her job "to look after Father, not you." It's clear that Mrs. Tredoni sees the Spages' relationship with Father Tom, both as a spiritual leader and a friend, as them sullying a man she has put on a pedestal. She doesn't want to share the priest with these people. And from the scene where Mrs. Tredoni gives confession to Father Tom right after she's killed Dom, it's clear that her emotional connection with Father Tom is, uh, intense. She acts like a schoolgirl with a crush, sighing and fawning over the priest in a way that feels inappropriate given the nature of their relationship.

So, at the film's conclusion, when Father Tom denies her communion (after giving it to Catherine, who Mrs. Tredoni reviles), the housekeeper's idolization of Father Tom no longer computes with her reality. Why would this man, who she has killed for, reject her like this? Her one-sided relationship with the charming young Father comes crashing down ... and so she reaches for the knife. If she can't have him, no one can.

An obscene twist on communion

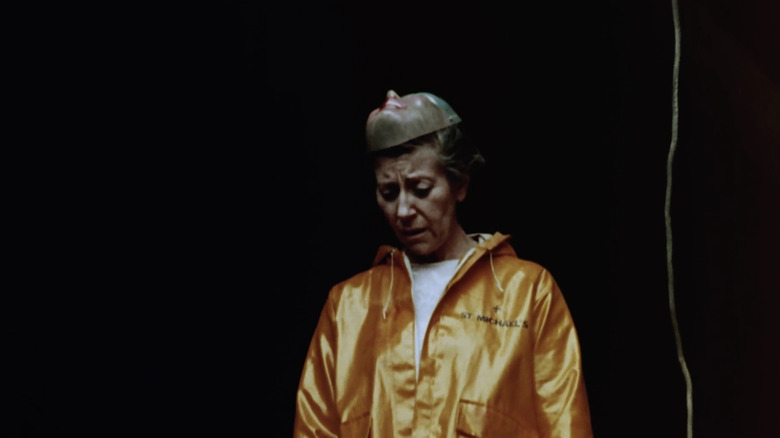

Out of context, Mrs. Tredoni's murder of Father Tom could be interpreted as nothing more than a grisly conclusion to a particularly violent slasher. Kneeling, Mrs. Tredoni's pleading face twists into a visage of fury. She thought Father Tom might understand her murderous "cleansing" of their church, or at the very least forgive her for it. But now here he is, clutching her hand, intent on handing her over to the police. Mrs. Tredoni reaches into her brown paper bag and pulls out the knife, plunging the blade into the priest's neck. Father Tom clutches at the wound, attempting to suppress the flow of blood. While the congregation looks on in horror, Mrs. Tredoni brings the dying Father in close, embracing him tightly while his blood streams down the back of her rain jacket.

Originally titled "Communion" before being acquired by Allied Artists, the holy sacrament is an integral part of "Alice, Sweet Alice." Communion involves consuming wine and bread — symbolically the body and blood of Jesus Christ — in commemoration of Christ's sacrifice. In "Alice, Sweet Alice," both Mrs. Tredoni and Alice have warped relationships with the eucharist. In rare moments of vulnerability, Alice earnestly takes communion in the hope that it will make her less of an outsider in the community. Meanwhile, Mrs. Tredoni sees the rite as an exclusive privilege that should only be reserved for the "pure." Mrs. Tredoni's twisted take on communion reaches its morbid conclusion with Father Tom's death: She kills his body, and she bathes in his blood.

Alice may not be sweet, but she is innocent ... for now

Little Alice Spages is clearly a troubled kid. She's in the throes of puberty and feels discarded by her parents, with a mother who dotes upon her young sister, Karen, and an absentee father who is starting a new family. She's aggressive and is displaying behavioral problems at school. And her cruelty towards animals (both Mr. Alphonso's kittens and her weaponized cockroaches) hints towards a disturbing lack of empathy. When Alice is detained at a mental health facility, Dr. Whitman (Louisa Horton) tells her parents that she desperately needs psychological help. And she's right. While therapy in the 1960s (especially for "troubled" young women) wasn't perfect, Dr. Whitman's assessment that Alice would benefit from the care of mental health professionals is sound.

Horror films have primed us to expect mentally disturbed individuals to be killers. And "Alice, Sweet Alice," preys upon our prejudices to misdirect our attention away from the real killer: the elderly Mrs. Tredoni. It's clear that Alice needs help and that she's struggling, mentally. But she's not a murderer. In the film's final shot, Alice wanders off with the bag containing Mrs. Tredoni's murder implements. With a blank expression, she contemplates the knife. She's at a crossroads. And if she doesn't get help soon, she may venture down the same murderous path as Mrs. Tredoni.

The final shot underlines the film's concern with parental neglect

In the final moments of "Alice, Sweet Alice," our titular troubled pre-teen walks solemnly away from the altar. While the congregants stand transfixed by Father Tom's tragic demise, and police rush forward to apprehend the murderous Mrs. Tredoni, Alice walks away unobserved. Sure, her mother held her tight after the stabbing, but somehow Catherine has once again lost track of her little girl (who, let's remember, was mere inches away from a brutal homicide moments earlier). Parental neglect is a key theme running throughout "Alice, Sweet Alice," with the Spages repeatedly having zero clue where their daughter is at any given time. Born out of wedlock (unlike her adored younger sister Karen, who was born at the "right" time), Alice is a pariah in her community, an embodiment of a taboo to be shunned.

This attitude extends to Alice's parents, who frequently abandon her to her own burgeoning psychopathic devices. "Alice, Sweet Alice" doesn't pass judgment on children born out of wedlock. But it is deeply concerned with what happens to children who are neglected and isolated within their homes and communities. And when you neglect children — denying them love, affection, and (oh, we don't know) support after they watch a murder happen right in front of them — you shouldn't be surprised that they're able to slip away with the murder weapon. If Alice is going to follow in Mrs. Tredoni's steps, the film seems to argue, it's because her family and community continued to isolate and "other" her.

Why did Mrs. Tredoni kill Mr. Alphonso?

While we would never wish death upon anyone, we can't say we were especially bereaved when Mrs. Tredoni murders Mr. Alphonso. A bonafide creep of the highest order, the Spages' lecherous landlord makes multiple sexual advances upon the 12-year-old Alice, forcing himself upon her in one of the film's most uncomfortable scenes. However, while we're relieved to see this horrible man's life snuffed out, it's not entirely clear at the end of the film why Mrs. Tredoni killed Mr. Alphonso. As she makes plain during the film's bloody finale, Mrs. Tredoni's murders are motivated by a desire to cleanse the congregation of those she considered "unworthy" of God's grace.

But Mr. Alphonso doesn't appear to be a member of the Church. We never see him leave his apartment, let alone attend Mass. One explanation that's bound to rattle around in your head while the credits roll is that Mrs. Tredoni murdered the landlord in an effort to frame Alice. But this conjecture only raises more questions: How did Mrs. Tredoni know that Alice would be a suspect in the event of his death? Was she aware of his sexual impropriety and looking to expand her "punishments" beyond her fellow congregants? Again, we're not sad to see Mr. Alphonso go, but why, exactly, he found himself on the pointy end of Mrs. Tredoni's kitchen knife is never fully resolved.

The film is a direct response to director Alfred Sole's relationship with the Catholic church

As we've discussed previously, "Alice, Sweet Alice," wears its religious criticisms on its sleeve. And while you sit with the film as the credits crawl by, you may start to wonder what happened in writer-director Alfred Sole's life to generate such a bitter attitude towards the Catholic Church. There is, indeed, a very good reason for Sole's contempt and cynicism.

In 1972, four years before the release of "Alice, Sweet Alice," Sole's feature film debut — an X-rated called "Deep Sleep" — was hit with obscenity charges that resulted in his formal ex-communication from the Catholic Diocese of Paterson, New Jersey, where "Alice, Sweet Alice," is set. In Catholicism, ex-communication describes the process of depriving a censured person of the rights of Church membership. Ostracized from his community, a pariah just like Alice, Sole's interest in telling a story about how religious communities self-destruct and cannibalize themselves in the name of safeguarding "purity" takes on a deeper, and far more personal, meaning.

Alice, Sweet Alice turns longstanding religious horror themes into red herrings

A good number of Catholic-themed horror films integrate faith-based fears into the genre. And "The Exorcist" — arguably one of the most famous and celebrated examples of Catholic horror — is a textbook example of two recurring themes: a fear of female sexuality and a concern for families that lack a father figure. Like the demonically-possessed Reagan MacNeil, a part of what makes Alice so strange is her "loss of innocence" as she enters puberty. Like the MacNeils, the Spages' patriarch is out of the picture, an aberration from the traditional family structure expected by the Church. Films like "The Exorcist" validate these religious fears as genuine, and worthy of concern. At the end of "The Exorcist," little Reagan reverts to her childlike, infantilized self and the family finds a new patriarch in the form of the Catholic Church.

Meanwhile, in "Alice, Sweet Alice," all of these same faith-based anxieties are completely irrelevant to the horrors taking place. Puberty and not having her dad around might be taking an understandable psychological toll on little Alice ... but they don't twist her into a vicious serial murderer. In fact, "Alice, Sweet Alice" goes one step further, arguing that the real danger lies in a culture of judgment that would be so cruel to others for simply living their lives.

The end of the film isn't about revealing the killer, it's about reinforcing its critique of the Catholic church

One of the many things that make "Alice, Sweet Alice" such a unique offering in the slasher genre is its abrupt switch from a "whodunnit?" to a "who-gonna-arrest-this-lady?" Yes, around the one-hour mark, "Alice, Sweet Alice" lets us in on the killer behind the translucent mask. Rather than the reveal letting the wind out of the film's sails, though, "Alice, Sweet Alice" pivots to an examination of Mrs. Tredoni's motives and the tension-filled events leading up to her capture. As such, the film's final moments aren't a Scooby-Doo-style villain reveal but rather a doubling down on the film's core theme. Namely: the hypocrisy of the Catholic church. Mrs. Tredoni kills to eliminate the sinners in her community, willfully ignoring the fact that killing is a sin. Likewise, Mrs. Tredoni's fixation on the Spages' conceiving out of wedlock feels ironic in light of her imbalanced and inappropriate sexually-coded possessiveness of Father Tom.

"Alice, Sweet Alice" wants us to consider what kind of community could engender the hateful, delusional worldview of individuals like Mrs. Tredoni. Is her perverse interpretation of Church teachings an aberration or the logical conclusion of puritanical belief?

Alice, Sweet Alice has been reclaimed as a cult classic

When "Alice, Sweet Alice" premiered in 1976, it was met with controversy. Critics like Ernest Leogrande of the New York Daily News praised the film's atmosphere and authenticity but took issue with the abundance of "improbabilities and red herrings." Meanwhile, other critics balked at the film's religious content, with Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times memorably condemning the film as "foul ... an obscenity."

In the intervening years, "Alice, Sweet Alice" has received a notable modern re-appraisal. In a positive 2005 review, Slant's Jeremiah Kipp remarked that because of the film's "strange brew" of Giallo, murder-mystery, and religious themes, "despite its considerable cult following — the film has never gotten the critical attention it deserves." As director Alfred Sole and editor M. Edward Salier note on the film's commentary track, because of drama with the film's copyright, "Alice, Sweet Alice" survived exclusively on the bootleg market until 1997. The most recent physical media release of the film was in 2019, with Arrow Films putting out a 2K blu-ray restoration struck from the original camera negative. All told, "Alice, Sweet Alice" is on track to persist in the form its director intended for years to come. Take that, 1970s critics!

Alice, Sweet Alice deserves more credit as an early American slasher

For many, the answer to the question "What was the first American slasher film?" is easy. John Carpenter's "Halloween" was a crucial gauntlet throw for the genre in 1978, fine-tuning the template that would go on to define what makes a Hollywood slasher film. A good deal of genre fans champion Bob Clark's "Black Chrismas" as the true "first" American slasher — which was released four whole years before audiences were first introduced to Michael Myers.

And sandwiched between those two films lies "Alice, Sweet Alice," which really deserves to be mentioned in the same sentence as its more-famous peers. As Jim Vorel of Paste Magazine writes, "Alice, Sweet Alice" is "one of the most idiosyncratic and chilling of the early slashers," offering up the genre's graphic, morally-motivated kills with a distinctly religious edge. While the slasher really hit its heyday in the early 1980s, the 1970s mark a critical and fascinating period where the genre was taking shape. And, for our money, "Alice, Sweet Alice" absolutely deserves credit for paving the way for the knife-wielding maniacs that followed in its stead. And as far as the "surprise — the killer's an old lady!" trope goes, Mrs. Tredoni walked so Pamela Voorhees could run.