Westworld's Cancellation May Disappoint Fans, But It Won't Surprise Those Paying Close Attention

HBO's cancellation of "Westworld" after four seasons was just the latest cost-cutting move since the Warner Brothers-Discovery merger. That context alone shouldn't be terribly shocking to anyone who has been paying attention to what the CEO of HBO's new parent company, David Zaslav, has been saying since the two entertainment behemoths became one in April. But despite its many obvious and significant flaws (and we'll get to those later), "Westworld" was unique and fascinating, and if it's not worth preserving, it has at least earned a proper memorial.

A network focused on adjusting the ledger after a widely reported poor third-quarter earnings report would be expected to target a show with a Season 3 price tag of $100 million (via Deadline). On a conference call with reporters to discuss those disappointing numbers, Zaslav didn't mince words about why "Westworld" found itself on top of WB Discovery's ever-growing trash heap. "We are being deliberate about measuring how the shows are doing... Let me be very clear, we did not get rid of any show that is helping us... It's a business of failure, but we'd rather take that money and spend it again and have a chance of having a show that will engage and delight." (via TechCrunch).

Westworld was very cool but very complicated

While even the staunchest "Westworld" fan will admit that the show could often frustrate, confound, and terrify, and the viewership numbers and fan feedback throughout the disappointing and confusing middle two seasons certainly weren't helping the network, the implication that "Westworld" did not "engage and delight" its audience is thoroughly preposterous.

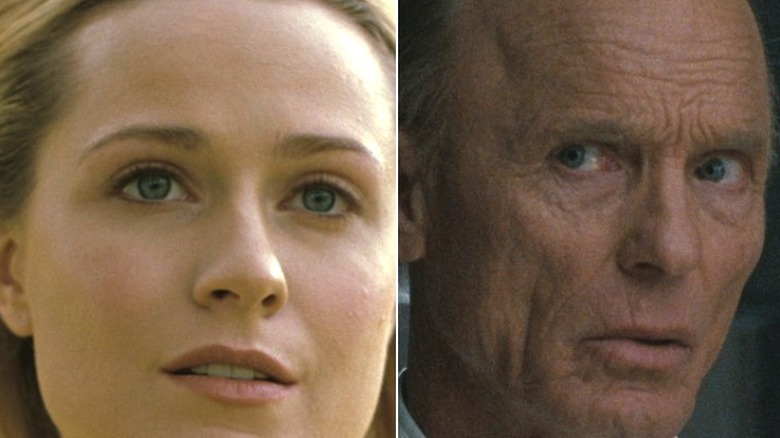

Although a flawed adaptation of an even more flawed 1973 Michael Crichton film of the same name, "Westworld" brought a remarkable premise to the small screen with utterly spectacular cinematography and masterfully executed practical and computer-generated special effects. Human guests and sophisticated robotic "hosts" interacted in a Wild West-styled theme park where the guests could exercise their basest urges without any real-world consequences for any violent or otherwise immoral acts they may choose to engage in on their very expensive vacations. Dolores Abernathy (Evan Rachel Wood) became the avatar for the hosts, and William/The Man in Black (Ed Harris) took on the same role for the guests before buying the park and transforming it into his own psychological and technological playground.

But "Westworld" quickly became tangled in its own mess of multiple timelines and storylines, and in a way, came to resemble the park that stood at its center, with the creators and unwitting actors playing the guests and hapless viewers sometimes left at the lesser end of a world where some could play willy-nilly without consequence while the others were left anywhere from mesmerized, to swirling in the wake of the "others," to bleeding out in the dirt (literally for the show's hosts, and metaphorically for the viewers.)

Death became meaningless as Westworld wore on

In a universe where any human consciousness could be coded into a golf ball-sized sphere and planted in a body of one's design and choosing, death — universally the most serious and unavoidable consequence in the human experience for bad decision-making and/or poor execution — quickly became meaningless. Even as Seasons 3 and 4 tried to convince us that the fate of all humanity was at stake, without the permanence of death, such a fight lost its stakes and meaning. Many, if not most, of the cast suffered multiple apparent demises only to return stronger than ever, including the four most primary characters: Charlotte Hale (Tessa Thompson), Dolores Abernathy (Evan Rachel Wood), Bernard (Jeffrey Wright), and William (Ed Harris). Bernard literally lost count of how many times he had died and rebooted himself, and William killed himself so many times in so many different settings that the character was left without a clear identity and was as confused as many viewers when Season 4 ended. When even the characters themselves don't know who they are, it's nearly impossible to get audiences to care. And even in a show and park where white and black hats became the marks of heroes and villains, it became equally as impossible to track which characters were on which side.

Not that the show should have been obligated to keep those lines drawn so clearly. In Season 4, shades of grey and splashes of color were introduced into Charlotte Hale's (Tessa Thompson) world in a clear indication that she didn't see the universe so starkly, even given her experiences in the human world and the park.

Westworld's entire legendary cast was done dirty by HBO's cancellation

Any celebration of "Westworld" must start by acknowledging the stellar cast — one that should go down in television history as one of the greatest ever assembled. Viewers were treated to Anthony Hopkins in 17 of the show's 36 episodes, but it was the performances of Thandiwe Newton, Tessa Thompson, Evan Rachel Wood, Jeffrey Wright, and Ed Harris which made "Westworld" so special. And any show that has James Marsden, Aaron Paul, and any Hemsworth (even Luke) as far down on the call sheet lik "Westworld" did is at least going to be worth watching.

Meanwhile, according to Deadline, the cast will still be paid for the unshot fifth season. With what they contributed over the first three dozen chapters, this amazing collection of actors needs to be turned loose on whatever conclusion to their story that Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy could come up with. In a statement through their film company, Kilter Films, the creators and showrunners said, "Making 'Westworld' has been one of the highlights of our careers. We are deeply grateful to our extraordinary cast and crew for creating these indelible characters and brilliant worlds. We've been privileged to tell these stories about the future of consciousness — both human and beyond — in the brief window of time before our AI overlords forbid us from doing so." (via Variety).

Westworld's demise isn't just on HBO's head

The subtle dig at the bottom-line mentality that has taken over one of the most successful video properties in entertainment history will likely go unheeded by David Zaslav and his ax-wielders at Warner Brothers Discovery, but by the end of Season 4, Nolan and Joy had built "Westworld" into a primary target for Zaslav's next round of cuts. While the show's massive budget made it one of the most likely moles to get whacked in Zaslav's cancellation spree, it was the over-complicated storylines and seemingly unresolvable split timelines that made "Westworld" sometimes such a frustrating and energy-consuming watch and drove its decline in viewership. While "Westworld" truly excelled in terms of story scope, character transformation, visual presentation, and cast performances, a 30 or 60-minute episode often required multiple viewings and post-episode recaps until it could even be marginally understood, and viewers quickly learned not to put much faith in any established "truth" the show presented.

Such twists and reveals can be compelling and fascinating, but Nolan and Joy packed so many of them into "Westworld" that we were left collectively holding a bag of broken mirror pieces, which is no fun to look at for an hour at a time.

They also wrote themselves into a hole with the ending of Season 4, which seemed to place the show and its remaining characters back at the start of the series in Dolores' virtual world but squarely in Armageddon in the "real" world.

Westworld's most compelling aspect is what killed it

That fragmenting of reality is what made "Westworld" so endlessly compelling from its brilliant start to its abrupt end, but it's also what served as a fatal flaw. Viewers need to be able to trust what they are being shown and told, and it just became impossible to track where the characters had been and where they might be going. In creating the park, Robert and Bernard envisioned a realm of endless possibilities. That's perfect for a fantasy theme park, but it makes for a very confusing television series.

Complex is good, but "Westworld" too often crossed the line well into "baffling" territory to keep audiences consistently engaged in a purely positive way.

Had the viewership for "Westworld" remained steady, we would likely be speculating on where Season 5 might take us instead of lamenting the loss of one of HBO's most innovative shows. But a network focused on numbers couldn't have been confident in a viewership rebound going forward. According to Statista, nearly 2 million Americans watched each episode in Season 1, but by Season 4, that number had dropped to around 300,000.

Any business that loses the overwhelming majority of its customers in four years will fail, and Warner Brothers Discovery has made it very clear that they are handling HBO and its properties as a business and not art. Like "Westworld," that is at the same time understandable and infuriating.