The Ending Of The Fabelmans Explained

Contains spoilers for "The Fabelmans"

Steven Spielberg's latest film "The Fabelmans" dramatizes his childhood leading up to his burgeoning career as a filmmaker. But even those of us who didn't go on to become world-famous, Academy Award-winning directors will still find this lovingly and painstakingly made mid-century dramedy to be charming and relatable. It's exactly the kind of movie that everyone — from kids to great-grandparents — can see together over the holidays, and it certainly can be viewed as a bittersweet, relatively small-scale coming-of-age story. The protagonist and stand-in for Spielberg himself, Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle), is trying to navigate his own personal and professional life in the midst of his parents' divorce, which is something a fair portion of people have lived through, whether they identify with Sammy, his mom (Michelle Williams), or his dad (Paul Dano).

However, there's much more to "The Fabelmans" than what's on the script pages. Though like all Spielberg's best work, it's glossy and entertaining, the melodramatic film is also many layers deep. Its director and co-writer is, like never before, mining his own life experience for meaning. Beneath the surface, "The Fabelmans" is concerned with bigger things than the dissolution of a single marriage or the career path of a single young man. It ponders more universal questions having to do with the nature of happiness, ambition, mental illness, commitment, sexism, and art. "The Fabelmans" is unabashedly about the transformative power of cinema, but it also compellingly explores why Spielberg (and people like him) are the way they are.

Movies give anxious Sammy a way to control the world around him

"The Fabelmans" begins in postwar America as Sammy's parents take him to his very first movie, 1952's "The Greatest Show on Earth." This choice of film serves two purposes. The actual content becomes an important plot point in the story, but the title signifies the reverence that a young Spielberg had for cinema. The way that Burt (Paul Dano) and Mitzi (Michelle Williams) prepare their son to take in a moving picture — helping him to distinguish between what's real and what's pretend — lets us pick up on the fact that Sammy might struggle with anxiety.

Sure enough, the train crash scene makes a profound impression on the young boy. Immediately after the credits roll, Sammy's gripped by fear and fixated on the death and destruction that would've resulted from an actual collision. But sensing his brilliant mind wants to work out how the filmmakers pulled it off safely, his parents gift him train cars for Hanukkah. He borrows one of his father's cameras and recreates the sequence, damaging the expensive model engine in the process. Sammy's mother, Mitzi, helps him complete the project in secret. Little Sammy crashes the train over and over again until he's copied "The Greatest Show on Earth" from every angle, then screens his first film for his mom.

The pre-time jump part of "The Fabelmans" not only tells audiences how Spielberg came to love the movies, but also how he (or worrywart young Sammy) came to use art — and to a different extent, control — to make sense of the world around him.

He realizes he's more like his mom than his dad

One of the threads that run throughout "The Fabelmans" is the tension between art and science. Though the audience can appreciate filmmaking as a product of both, Sammy's family views them as diametrically opposed. His mother factions the family into artists and scientists. Stable, boring Burt is the scientist. Passionate, nonconformist Mitzi is the artist, and she thinks Sammy's one, too.

To some extent, the Fabelmans view themselves and these concepts so differently because of the times they live in. Burt is a leading computer engineer whose job takes his family all over the country. He finds success relatively easily on his merits, but he's able to leave work at the office. Mitzi could've been a concert pianist, but either because she wanted to or because it's what was expected of her, she traded in her dreams to become a wife and mother. It's obvious she's not as happy as she thinks she could be. She's bad at and dislikes domestic work (the family dines with plastic tablecloths and disposable dishware), and piano playing has become a hobby instead of a career, though one she's compelled to do the way Sammy feels compelled to make movies.

But whether Mitzi's inner turmoil stems from her situation or her disposition is an open question ... one that Sammy wrestles with throughout the movie. His mom is more supportive than his dad, and he's closer to her than anyone else, but while he may inherit his artistic gifts from Mitzi, he also wonders if he shares her tilt toward mania.

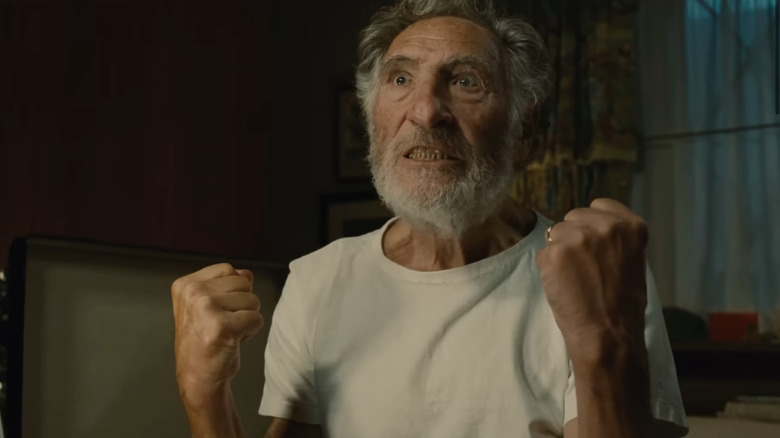

His great-uncle's visit puts things in perspective

After Mitzi's mother (Robin Bartlett) dies, Uncle Boris (Judd Hirsch) — who Grandma Tina had warned them about — shows up unannounced. He's the kind of guy whose life story sounds like a collection of tall tales, and when Sammy's forced to share his bedroom with the practical stranger, he learns that some of them were true. Boris, who was around for the early days of Hollywood, considers himself an artist, too. Between his mysterious transient past, Tina's premonitions, and Mitzi's eccentricities, we're meant to understand that Sammy comes from a long line of creative but quirky personalities. Boris laments that Mitzi never got her shot at stardom, and in a pivotal conversation, he encourages Sammy to embrace the madness and the maker within him, no matter what.

Boris' take is that artists don't just make art because they can or because they have the talent. The kind of music Mitzi wants to play, the kind of movies Sammy wants to make ... they aren't something that can be accomplished in hobby form. Uncle Boris contends that great art requires almost total commitment of the soul, to the detriment of everything else, including one's relationships. In what's sure to be an oft-memed moment, he crosses his arms over his chest, then mimics ripping his heart apart. The implication is that if Sammy pursues film — which Boris thinks he should — it will come at an emotional cost. Not only is working in the arts frustrating and often crushing as a professional endeavor, but he'll also have to sacrifice his personal life to an extent that people with "normal jobs" (like his dad) won't.

Sammy figures out the truth about Mitzi and Bennie

As his mother lingers in bed, depressed, Burt commissions a reluctant Sammy to make a movie for and about Mitzi in an effort to cheer her up. The teenager is eager to get back to the big project he had planned, but eventually he sits down at the editing machine and starts to assemble the footage of his mom. When he's able to focus on her life, cell by cell, the evolution of Mitzi and Bennie's (Seth Rogen) friendship into a forbidden romance becomes the story. Sammy finishes the movie, leaving the damning parts on the cutting room floor. He holds onto his anger for a while and occasionally lashes out at his mom and sisters.

That anger rears its head during an explosive fight between Sammy and Mitzi that ends with her slapping him on the back, leaving a red handprint. Mrs. Fabelman is ashamed and tries to make amends, which is when an equally regretful Sammy finally shows her the stolen moments his camera captured between her and Bennie. This is a point of no return for Sammy, both as a member of the Fabelman family and as a young adult. Every child reaches a point where they realize, for better or worse, that their parents are human. Sammy knows this revelation will forever change his relationship with his mom, and probably her relationship with his father and Bennie, who's been a presence throughout his life. It also uproots his life yet again when Mitzi agrees to move to California for Burt's new job, leaving Bennie behind.

He faces anti-Semitism

Just as Mitzi doesn't acclimate well to her new life in California, Sammy has a hard time fitting in at his new high school from the very start. Before anyone has a chance to really get to know him, he runs afoul of a gang of bullies led by macho, womanizing Chad (Oakes Fegley) and Logan (Sam Rechner). At first, these pugnacious jocks target Sammy just because he's new, small, and nerdy, which makes him an easy target. But once word gets out that he's Jewish, he's othered from the rest of the students to a more problematic degree. Even the kids who don't dislike him still fixate on how he's different, which makes Sammy — who's already down in the dumps because of his family situation — even more withdrawn.

Sammy attempts to stand up for himself by snitching to Logan's girlfriend about his stairwell kissing session with another young woman. That he challenges the bullies gives them an excuse to escalate their torment with anti-Semitic threats. In the film, this takes the form of verbal harassment and a bagel hung in his locker. This unfortunately once-again timely issue affected Spielberg in real life at his alma mater, Saratoga High School, where students threw pennies at him and yelled slurs. The bigotry that isolated him from his peers as a teenager also made him less confident in his early childhood. He has since used his chosen medium to explore anti-Semitism in "Schindler's List," "Munich," and two "Indiana Jones" films as well as through the Shoah Foundation, and he's explored prejudice in general in movies such as "The Color Purple," "Amistad," "Lincoln," "West Side Story," and a six-part documentary he executive-produced, "Why We Hate."

He gets (and loses) his first girlfriend

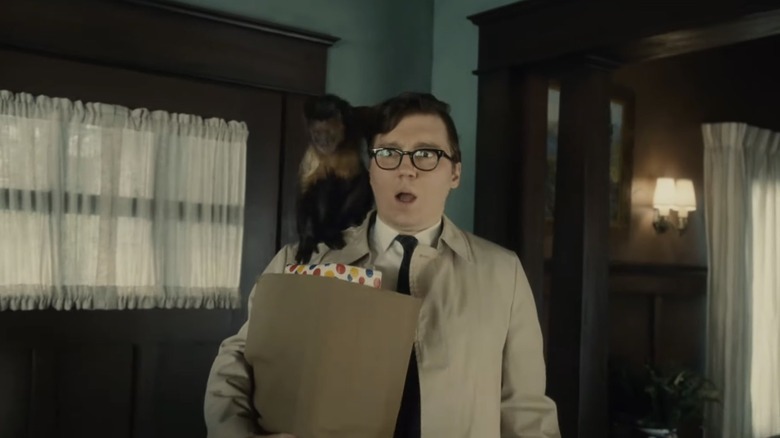

Through Logan's girlfriend, Sammy meets Monica Sherwood (Chloe East), a pretty, preppy, Christian girl who runs around with the alpha crowd. In an uproariously funny turn of events, Monica takes an interest in Sammy explicitly because of his religious heritage. During their initial interactions, the audience thinks that Monica is the type of boy-crazy teeny bopper who's simply rebelling against her parents, eager to date someone she deems exotic. Once Monica brings Sammy home, her attraction becomes hilariously much more specifically clear.

Monica's family is thoroughly culturally Christian and she seems to have taken the love and devotion she's expected to have for her lord and savior perhaps too literally. She has a bedroom shrine to Jesus Christ the way other girls may have had wall space devoted to Elvis, the Beatles, or David Cassidy. In her heavy-handed efforts to get Sammy to kiss her, she reminds him that Jesus was Jewish, too. Not particularly popular, Sammy doesn't mind being fetishized if it means he lands his first girlfriend. The deal gets even sweeter when he learns that her dad works in the industry and can loan him high-quality film equipment.

Things are going great between Sammy and Monica until life gets in the way. Stressed out over his parents' pending divorce and completely forgetting Uncle Boris' advice, Sammy impulsively tells Monica that he loves her and insinuates that they should get married at their senior prom. He asks her to forgo her own college education and run away with him instead. Monica politely declines, which — though he's hurt — is a good thing for Sammy in hindsight.

A bully helps him figure out why he makes movies

Sammy put away his camera after his discovery of his mother's affair, but — sorely needing a way to fit in at school — he volunteers to direct and record the senior class "Ditch Day." While the other kids are having fun swimming, laying out, and playing sports on the beach, Sammy is having an even better time staging shots (like one in which faux bird poop plops onto beachgoers' faces) for his Ditch Day movie. When the final product airs at the senior prom just after he's been dumped, Logan (the bully) is unsettled to see that Sammy's made him out to be the hero of the story.

He thinks the nerd might be making fun of him (he's not), then confesses that the weight of the expectations upon him is much more crushing than he lets on. He asks Sammy why he did it. The amateur auteur answers that maybe it was because he wanted people to like him, or maybe it was because he wanted it to be good, and the Ditch Day movie was better with Logan as its golden boy. The truth is probably somewhere in between, or it's fully both. Steven Spielberg is one of our most accomplished living directors, with more good movies to his name than practically any other filmmaker, and most of them are likable movies with broad appeal, such as the one Sammy made.

Sammy and Logan's chat comes to an end when the latter warns the former never to speak of it and Sammy swears he won't. It's a safe bet that this really happened, since Sammy's promise comes with a wink to the camera and the audience.

Sammy worries about his life choices

Sammy's relatively uneventful life unravels after he figures out the truth about his mother. She tries to put the affair behind her, but lapses ever deeper into depression and conspicuously buys a pet monkey, whom she names after Bennie. Mitzi eventually returns to Bennie, leaving Sammy and his sisters behind with his forlorn father; the kids' sympathies split are between their parents.

Things aren't going much better for Sammy. After Monica breaks up with him and he graduates, Sammy gives college a try, mostly because his dad insists. It doesn't go well, and a year in, Sammy is more lost and distraught than he's ever been. Mitzi sends them some old photographs, and they both realize that their lives were never as picture-perfect as they might've assumed. It's painfully clear that Sammy wants to quit school, but his dad wants to make sure he'll have at least a secure if not completely happy life.

At precisely that moment, Sammy gets a letter that changes his life. He'd been sending out applications to studios that weren't necessarily hiring, just trying to get his foot in a door. Somebody wants to meet him about an entry-level opportunity, which is all the encouragement he needs to plow forward with his dreams. Sammy's renewed enthusiasm is all the assurance Burt needs to support his son in his endeavors.

He meets one of his heroes

While the climaxes of most Steven Spielberg movies have to do with alien spaceships, shark attacks, dinosaurs running rampant, and epic battles, the climax of "The Fabelmans" is simply two people talking about paintings in a room. Nevertheless, it's one of the master director's most memorable and affecting conclusions. When a producer tells the young go-getter that there's someone he wants to meet, an administrative assistant ushers him into an office. He scans the walls while he waits and realizes the someone is legendary director John Ford — played by David Lynch — the man behind such all-time classics as "Stagecoach," "The Grapes of Wrath," and "The Searchers." That Sammy's first homemade films are Westerns that copycat Ford's style gives us a clue as to how completely awestruck he is.

Spielberg's films can be schmaltzy (often in a satisfying way), but the brief scene that unfolds between Sammy and his idol is anything but. Ford, storms in as callous and indifferent to Sammy as the desert landscapes that decorate his personal space. He has little time for this random teenager, but he deigns to teach Sammy his first real lesson about being a director. Ford asks the wide-eyed wannabe what he thinks about his artwork. Sammy stumbles to say something smart-sounding, but an impatient Ford blurts out the answer. When the horizon line falls in the middle of the frame, it's boring. When it doesn't, it's interesting. That's the secret. Sammy is dismissed unceremoniously and in such a way that might've left another person in tears, but it's clear he's just experienced the best moment of his life.

The last shot is an in-joke

"The Fabelmans" ends as Sammy chooses to drop out of college and pursue filmmaking full-time, starting from the very bottom of the ranks. In fact, he doesn't even have a job lined up yet. Still, after his chance encounter with John Ford, he's practically levitating as he walks through the studio with his back turned to the camera, embarking on the adventure that will be his career. This — an aspiring young director framed by a backlot and an open sky — would be a hopeful and appropriate note to end on. But at the very last second, the camera shifts so that the horizon line is no longer in the center of the frame, putting into practice the very advice Ford had just given Sammy Fabelman only minutes ago.

The in-joke itself is pretty hard to miss. It's a cute and clever wink to the craft of filmmaking that gets a hearty laugh in the theater, and many critics have already praised the shot. But as is the case with most things in "The Fabelmans," there's another deeper meaning to this sly gimmick. That the camera moves implies someone is actively making this movie in real-time. That someone is the director, whether we want to interpret that to be a much older Sammy or present-day Spielberg himself. In either case, he's pinpointing this as the formative moment that began his film education and career in earnest. There's nostalgia and humility in that slight adjustment that makes a movie that could've easily been egocentric into something much more self-reflective.