Yellowstone Creator Taylor Sheridan Is Sick Of Hearing Those 'Red-State' Show Claims

On November 13th, "Yellowstone" Season 5 will premiere on Paramount Network, 10 months after its record-breaking Season 4 finale drew in 11 million viewers. Though the show has performed exceptionally well and given rise (for better or worse) to multiple spin-offs and a prequel, it's been largely ignored during awards season, while other antihero and dysfunctional family soaps (see: "Succession," with its numerous nominations and wins) have continually cleaned up.

As The Atlantic's Sridhar Pappu points out, artistic merit is only partially to blame for the gap in recognition between two such similarly structured series. "The critical disparity is also accounted for by the cultural and political bubbles we've sorted ourselves into," he writes, adding "'Succession' — depicting and aimed at coastal elites —makes noise on Twitter and at awards shows." Professor Tressie McMillan Cottom, in an interview with KCRW, put it even more bluntly: "Liberals that are watching [Yellowstone] don't think of it as a show to discuss. [It's not a] show that represents their identity in the way that it does for conservative viewers."

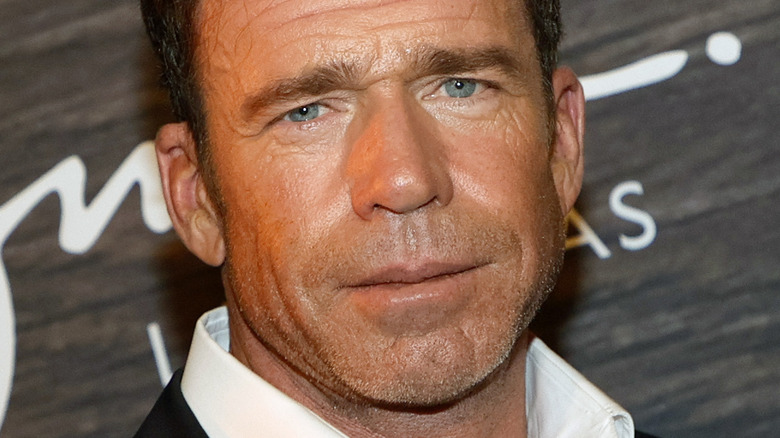

Speaking to Pappu, "Yellowstone" creator (writer, and director) Taylor Sheridan responded to viewers who see the series as a "red-state" show — a characterization with which he fervently disagrees. "I just sit back laughing," Sheridan said, adding "I'm like, 'Really?' The show's talking about the displacement of Native Americans and the way Native American women were treated and about corporate greed and the gentrification of the West, and land-grabbing. That's a red-state show?"

Montana politics aren't a microcosm of national politics

In Sheridan's defense, the show did indeed touch on all these things in its first two seasons, and as Pappu concedes, "'Yellowstone' doesn't have an explicit ideology that maps onto a traditional red–blue spectrum." Given its setting, that makes sense.

Despite having gone red in 15 of the last 17 presidential elections (via 270towin), Montana is known for its decidedly independent streak and complex politics. Not only is it an enormous state that differs wildly — both geographically and politically — from one region to the next, but it's also a state with hyperlocal and regional concerns (e.g., fracking, the rewilding of wolves) and a long and storied history of political and social contradictions (via Zocalo). The early focus that "Yellowstone" put on the displacement of Native Americans spoke to a reality that (despite being a reality for the whole country) is at the forefront of the discussion in Montana politics in a way it simply isn't in other regions (via Great Falls Tribune). That this theme was largely dropped in Seasons 3 and 4 was to the series' detriment, particularly considering, as McMillan Cottom points out, "It's one of the few big budget shows on television right now that has a fully fleshed out Native American cast of characters."

It's easy (and becoming increasingly easier, given our current political divide, per NYT) to categorize rural dramas as red drams, and glossy urban dramas (see: "Succession") as blue. But the "rural vs. urban" culture war has been raging for centuries, and it doesn't always line up perfectly with this simplistic understanding of national politics — a topic the series almost never dives into in its bid to keep things exclusively titular and western. And yet ...

Is (this) Western anti-hero really that different from more liberally lauded antiheros?

That so many of the values imbedded in the old-school cowboy mythology — values John Dutton is proposed to have, such as loyalty, integrity, hard work, and respect — are often at the center of so much conservative rhetoric has very little to do with actual politics, and everything to do with marketing them. Regardless of your political alignment, there are few people who wouldn't consider those values admirable. In fact, they're the same values we admire — and use to justify our love of literal, if fictional, murderers — in everything from Jersey-based mafia stories to Westeros-based power struggles and Birmingham-based gangster narratives.

Still, it's hard to ignore the fact that John Dutton embodies the idea of conservatism in its most literal and lower-case form: he wants to hold on to, aka conserve, his way of life, whatever the cost ("I am the opposite of progress," he says in his gubernatorial campaign speech). But John Dutton isn't the series' only (nor is he its most compelling) character, and "Yellowstone" maintains its ambivalence about just how much it wants us to like the Dutton patriarch. When Kayce (Luke Grimes) chooses his family over his wife in Season 4, we're clearly meant to see his taking up John's mantel as Kayce's turn to the dark side. What's more, despite the season's struggle to gain its footing plot-wise, as Forbes' Paul Tassi outlines, it at least left viewers with far more sympathy for Wes Bentley's progressive Jamie than for his father.

Yellowstone reveals more than it promotes

Admittedly, Season 4's treatment of Piper Perabo's Summer Higgins, a naive and easily seduced vegan whose very name feels like an exercise in caricature, didn't exactly help its red-state reputation. But "Yellowstone" didn't become the spin-off birthing phenom that it is or draw in 8 million viewers for its last season premiere (via Deadline) by being a straightforward soap box for Republican ideology.

Like any successful series, "Yellowstone" gives viewers the ability to indulge in an attractive fantasy. In this case, that fantasy is the idea that ends can justify any means so long as those ends are rooted in something (even vaguely) admirable. It's the same fantasy that had us rooting for Bryan Cranston's Walter White, Emilia Clarke's Daenerys Targaryen, and Jodie Comer's Villanelle, and although the setting, mythos, and central protagonist's "ends" in "Yellowstone" appear to matter more directly to a rural, conservative audience, the reality is the series has done more to reveal various aspects of the national political divide (albeit inadvertently) than it has ever done to weigh in on it.

How else to explain the fact that, despite being ignored by the awards show crowd, it's found its way into so many articles (e.g., The NYT, Time Magazine, The Atlantic, Forbes, and The Guardian) whose analysis of the series says more about the nation's divided agenda than it does about the series' supposedly red one?