14 Horror Noirs To Watch If You Loved Angel Heart

As its nomenclature suggests, the "film noir" genre was first coined by the French. Film-loving writers like Nino Frank — whose 1946 essay in L'écran français is generally accredited as the "birth" of the term — used "film noir" to describe a trend in American films they missed out on during the Nazi occupation.

This strain of crime films contained a suffocating darkness, hardened pessimism, and the disillusionment felt everywhere in the wake of World War II. Morally ambiguous private eyes and cruel city streets felt appropriate given the state of things.

There is no singular checklist for what defines noir. But if there is any one reliable way to spot a noir in the wild, it's that they are incredibly dark, both in tone and in their unmistakable use of murky, high-contrast cinematography.

Between all the killings, sleaze, and moral ambiguity, the line between noir films and the horror genre is about as thin as a shadow. Case in point: Alan Parker's 1987 film "Angel Heart," which follows Harry Angel (Mickey Rourke), a down-and-out private investigator who is hired to find a missing barfly in New Orleans. As the ritualistic murders begin to climb and Angel's amnesia and unpaid debts take on a sinister Faustian angle, "Angel Heart" leans hard into noir tropes and the southern gothic tradition with equal enthusiasm.

Ostensibly, horror fans have to pass the mic to film noir once November hits. But fans of "Angel Heart" who are amenable to the idea that horror and noir are frequent bedfellows will tell you that the ghoulish delights of spooky season can continue on into "Noirvember," if you so choose. So, fans of "Angel Heart," read on for our look at other notable horror noirs worth checking out.

Cat People

You wouldn't know it from Paul Schrader's erotic, practical effects-heavy 1982 remake, but 1942's "Cat People," is indeed a film noir. Directed by Frenchman Jacques Tourneur — whose work features not once, but twice on this list and who readers might know for the unmissable satanic mystery "Night of the Demon" — "Cat People" also benefits from the producing power of Val Lewton, the Ukrainian powerhouse behind much of RKO Pictures' success in the 1940s.

When Serbian fashion designer Irena (Simone Simon) meets all-American Oliver Reed (Kent Smith), the pair instantly fall in love. Unfortunately, the couple's matrimonial bliss begins to curdle when Irena becomes consumed with anxiety about her purported hometown curse: a folk legend that warns that strong emotions (like arousal) can change villagers into panthers.

Irena grows increasingly afraid that consummating their marriage will transform her into a man-eater and the distance grows between her and Oliver. When Oliver goes to his colleague Alice (Jane Randolph) for a shoulder to cry on, Irena's blood begins to bubble with jealousy, which has grisly and tragic consequences.

Featuring stark black-and-white photography from the great Nicholas Musuraca, "Cat People" seamlessly blends procedural noir tropes with genuinely creepy horror beats, including one of the greatest and most influential jump scares of all time.

Eyes of Laura Mars

Provocative fashion photographer Laura Mars (Faye Dunaway) unwillingly finds herself in the middle of a murder investigation. As if being hounded by accusations that her photography glorifies violence wasn't bad enough, Laura begins to experience first-person visions of the perspective of the killer who's been murdering her friends and colleagues. Laura's grip on reality begins to wane when she realizes that the killings are mirroring her own work ... and her budding romantic relationship with the lieutenant in charge of the case (Tommy Lee Jones) only muddies the waters further.

"Eyes of Laura Mars" premiered in 1978, the same year that its screenwriter, John Carpenter (yes, that John Carpenter) released "Halloween." And while Carpenter's iconic masked slasher marked a new, and distinctly American, branch in the murder-mystery tree, "Eyes of Laura Mars" has a much stronger family resemblance with the giallo genre.

As a result, Irvin Kershner's blood-chilling supernatural tale takes on a notable noir aspect. Morally suspect law enforcement? Check. A killer on the loose? Check. Bold, expressionistic cinematography? Check.

Hangover Square

George Harvey Bone (Laird Cregar) is teetering on the edge of greatness. His life's work — an intense, piano-driven concerto — is nearly finished and his peers are adamant that international fame is just around the corner. But lately, George has been experiencing blackouts: gaps in his memory seemingly brought upon by high stress and disagreeable sounds.

More troubling still: George's latest bout of amnesia has coincided with a grisly stabbing. Was he responsible? Could his subconscious self really have done something that senseless and violent? As the concerto premiere looms, Geroge finds himself in the clutches of an exploitative songstress ... and the suspicious tragedies continue to pile up.

There's a reason "Hangover Square" feels especially "Hitchcock-y." For starters, Both Cregar and director John Brahm's previous project was "The Lodger," a remake of Hitchock's 1927 film of the same name. Furthermore, its suspenseful soundtrack is indeed the work of "Psycho" composer Bernard Hermann.

But more to the point, "Hangover Square" is an adaptation of a play by Patrick Hamilton, the same man who wrote both "Rope" (adapted by Hitchcock in 1948) and "Gas Light," a formative psychological thriller which was adapted for the big screen in both 1940 and 1944).

With long shadows, expressionistic lighting, and a believably cruel femme fatale in Linda Darnell's Netta, the noir genealogy of "Hangover Square" is front and center. Its identity as a horror film is a little sneakier, but the "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" slasher angle is suitably terrifying twist that culminates in a fiery crescendo that must be seen to be believed.

The Invisible Man

1933's "The Invisible Man" was directed by James Whale — the same man behind other Universal horror classics like "Frankenstein" and "The Bride of Frankenstein." Based on H.G. Wells' 1897 novel of the same name, Whale's film begins with a man in crisis: Dr. Jack Griffin (Claude Rains) has turned himself invisible ... and he has no idea how to reverse the effects. Cloaked entirely in bandages to hide his secret, Griffin holes himself up in the Lion's Head Pub to create the antidote for his experimental drug. Unfortunately for our antihero (and the neighboring townsfolk), Griffin's invisibility has also driven the scientist completely insane. And the last person you'd want to be invisible is a homicidal maniac.

As the podcast "The Monsters That Made Us" explains in their coverage of "The Invisible Man Returns," Universal horror began to adopt the language of film noir as the genre came into its own in the 1940s. But even in the early 1930s, the germ was there, mutating in the wake of German Expressionism and Pre-Code crime films like "The Public Enemy" and "Scarface."

And if you look hard enough, you can spot some early rumblings in "The Invisible Man," with its stark shadows, concealing trench coats, insidious paranoia, unapologetic sleaze, and long sinister shadows ... without any apparent source.

Cast a Deadly Spell

Did you know, dear reader, that Martin Campbell (the guy who directed "GoldenEye" and "Casino Royale") made a horror noir TV movie? Well buckle your seat belts, because we're about to sing the praises of one of the great hidden gems of the early 1990s.

Set in a fantastical 1948, "Cast a Deadly Spell" follows hard-boiled private detective Harry Philip Lovecraft (Fred Ward), the one man in Los Angeles who doesn't use magic. Hired to recover a stolen tome of immeasurable occult power, Lovecraft must find the book, lest the folks who stole it reawaken the Outer Gods.

Yeah, yeah, "Cast a Deadly Spell" has zombies and eldritch abominations in it. But there's also an endless supply of cigarettes, a femme fatale played by Julianne Moore, and old partners who've turned to the dark side. If you ever wanted to know what it would be like if "Who Framed Roger Rabbit" (a great noir comedy, by the way) got in a three-way car wreck with "Dick Tracy" and Clive Barker's "Nightbreed," this film has got your back ... which is presumably cloaked in a trench coat and ample amounts of cigarette ash.

The Leopard Man

A maniac who kills like a cat is on the loose ... then again, there certainly is a lot of material evidence to suggest that the grisly murders were actually committed by a leopard. But what's a leopard doing in New Mexico? A big jungle cat did just escape from its enclosure at a local nightclub. Could it be that a real-life leopard is inexplicably staying within the city limits and picking lone women off one by one? Or is the alcoholic club promoter Jerry (Dennis O'Keefe) committing these heinous acts while stumbling around in a booze induced stupor?

An antecedent to the slasher genre, "The Leopard Man" is a swirling melange of unease and terror based on a looming and inevitable threat that lurks in the shadows of every dark alley. Released in 1943, "The Leopard Man" merges its rich gothic atmosphere with a compellingly pulpy murder-mystery, blurring the line between reality and fantasy in the New Mexico moonlight.

"The Leopard Man" is easily the more grounded of Tourner and Val Lewton's RKO collaborations. But with a decisive eeriness and just enough supernatural suggestion to raise audience arm hairs, the constant reminder of the town's violent colonial history feels nearly cosmic, like a cycle of violence echoing down the decades.

Constantine

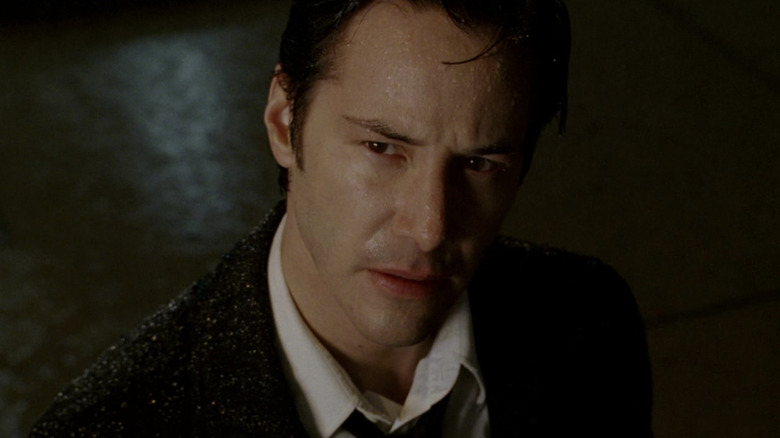

While Francis Lawrence's 2005 adaptation might not be the most faithful adaptation of the DC comic book anti-hero of the same name, the fact remains that "Constantine" absolutely rules.

John Constantine (Keanu Reeves) is a grizzled paranormal P.I. — a freelance exorcist and hardened cynic, really – who's as hard-boiled, and cigarette happy as they come. To be fair, Constantine has literally been to hell and back. And his brush with the afterlife left him with the ability to see the angels and demons that walk amongst us like the supernatural gangsters who prowl the city's underbelly, vying for control of mortal souls.

One day, a dame knocks on Constantine's door: the appropriately-named Angela (Rachel Weisz), an LAPD detective with a hunch that her twin sister's death was tied up in the supernatural. Together, they team up to determine who (or what) is responsible.

With cinematography emphasizing sharp shadows and enough film noir calling cards to play poker with, "Constantine" is a reminder that what we now call "superhero movies" used to dabble more boldly in established film genres. Horror-action-neo-noir doesn't exactly roll off the tongue. But damn if it doesn't make for one hell of a film.

Dementia

As if being a film noir with horror elements wasn't enough, "Dementia" also just so happens to be — and this is the technical term — experimental nightmare fuel. While resting in a cheap motel, a woman (Adrienne Barrett) wakes up, wild-eyed, from a nightmare. Stumbling around skid-row, caught between reality and a fever dream, the woman encounters a slew of grotesque characters in a hostile environment keen to push her already fragile mind over the edge into homicide.

Dialogue free (save for the cryptic presence of an unseen narrator), "Dementia" employs the shadowy visual language of film noir to emphasize its main character's paranoia, the grime of her nightmarish surroundings, and the lurking thought that all of this might be some sick dream. A portrait of a degrading mind as seen from the inside out, "Dementia" is patently uninterested in tying its chilling horrific interludes together in an easily digestible package.

All told, John Parker's 1955 labor of love is difficult to slot into any one genre, which is likely why "Dementia" fell into obscurity after the film premiered in 1955. Being banned by the New York State Film Board" for being "inhuman, indecent, and the quintessence of gruesomeness" probably didn't help (via BFI). But such is the price for making one of the great horror noirs of the 20th century.

Lord of Illusions

Nix (Daniel von Bargen) has gone too far. Kidnapping a little girl was the last straw. With Nix's golden boy Philip Swann (Kevin J. O'Connor) leading the charge, the rebellious cult members restrain their magic-wielding leader, fitting him with an iron mask and burying him deep within the Mojave desert.

Surely that's the last we'll see of this nefarious warlock, right? A decade or so later, P.I. Harry D'Amour (Scott Bakula) finds himself at the center of a string of deaths that all point to Nix's return. Before D'Amour can wrap his reeling mind around the fact that magic exists, he and Swann's wife Dorothea (Famke Janssen) find themselves up to their eyelids in a battle between good and evil.

Directed by Clive Barker and adapted from his own short story "The Last Illusion," this 1995 genre mish-mash blends horror beats with noir iconography. Harry D'Amour is truly one of the great grizzled gumshoes: a worn-down, world-weary private dick who thought he'd seen it all before ... uh, my notes say "cult members intentionally getting glass in their kneecaps to pay homage to their incredibly evil leader." Huh.

In the liner notes of the 1996 unrated director's cut, Barker clarifies that "Lord of Illusions" had even stronger noir vibes before studio meddling but "they wanted a simpler picture" (via CliveBarker.info). To think of what we could have had! Even so, "Lord of Illusions" still scratches the horror noir itch.

The Seventh Victim

Precocious teenager Mary Gibson (Kim Hunter) receives some startling news: Her private boarding school hasn't received any tuition payments from her older sister Jacquline (Jean Brooks) in the last sixth months. The school has tried to contact Jacquline without success, so the concerned Mary sets off to New York City to try and find her sibling on her own.

Mary's investigation drums up more questions than answers. Why did her sister keep her marriage a secret? Why has she sold off all her holdings in the perfume company she works for? And how seriously should Mary take the cryptic rumors that her sister ran afoul of a secret, underground society of witches?

Soaked in an ominous occult atmosphere and brimming with palpable menace, 1943's "The Seventh Victim" takes the criminal underbelly of film noir and swaps it out for something a little stranger and more satanic. There's a reason Val Lewton makes several appearances on this list: The RKO producer's uncanny ability to pair paranoia, loneliness, and mystery are integral ingredients in the intersection of horror and noir.

Brimming with ill omens and bone-chilling nihilism that anticipate "Rosemary's Baby" 25 years later, this overwhelmingly atmospheric mystery is a must-watch for anyone looking to cross the streams between film noir and horror.

Les Diaboliques

Michel (Paul Meurisse) and Christina Delassalle (Véra Clouzot) run a boarding school just outside of Paris. While the school is, in fact, Christina's, her abusive husband calls all the shots and blames his wife's weak heart for her inability to take charge. Michel's brutish behavior would be more than enough to send any woman straight to a lawyer. But because Christina's Catholic faith forbids her from divorcing her terrible husband, she starts to contemplate murder with the help of her friend, Nicole (Simone Signoret).

However, once the murder has been committed, strange things begin to take place around the school. Someone knows what they did, Michael somehow survived, or they are completely insane. Then, of course, there are more ... supernatural possibilities.

Directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot (whose 1943 film "Le Corbeau" will no doubt interest readers of this list), "Les Diaboliques" predates the likes of "Psycho" and "Repulsion" with its shocking integration of criminal thrills and psychological horror.

As Claire Gorrara notes in "The Roman Noir in Post-War French Culture," Clouzot's film is a part of a larger cinematic trend in which French filmmakers were responding to the shadowy, pessimistic American crime films that they had missed during Nazi occupation. A suspense-filled, shadowy slow burn that is an essential viewing for film noir and horror fans alike, "Les Diaboliques" lives up to its name and then some.

The Beast Must Die

Not to be confused with the 1952 film or 2021 TV series of the same name, 1974's "The Beast Must Die" is a bit of an unconventional inclusion on this list. The film has a lot more in common with Agatha Christie-style ensemble murder mysteries than it does Philip Marlowe. But a little hair-splitting never hurt anybody. Especially when that hair comes off the back of ... a werewolf!

An eccentric millionaire invites a group of choice individuals to his rural English mansion, only to reveal that one of the party is, indeed, a lycanthrope. Who could it be? The pianist and his student-now wife? The diplomat? What about the werewolf expert? With a procedural bent, the guests subject themselves to all manner of tests to ferret out the threat.

Confined within an estate that doubles as a prison, "The Beast Must Die" is filled with red herrings, treacherous dames, and werewolf-hunting helicopters. Now that's a party we'd like to attend.

Wolfen

A series of grisly murders are ripping through New York City, leaving a string of victims as nothing more than crimson smudges on the sidewalk. While ceaselessly hungover NYPD veteran detective Dewey Wilson (Albert Finney) would like nothing more than to dismiss the killings as unconnected tragedies, his instincts tell him otherwise. Soon enough, Detective Dewey stumbles upon the horrible truth: a supernatural underbelly of man-eating predators.

Released in 1981 — improbably also the same year that both "The Howling" and "An American Werewolf in London" hit screens — "Wolfen" infuses police procedural beats with supernatural horror.

This genre melding is most obvious in the way the film represents New York City. This isn't somewhere people live: It's an oppressive and ominously gloomy landscape where menace lurks around every corner and stalks every shadowy back alley.

As if that delicious blend of genres weren't enough, Michael Wadleigh's sophomore flick also includes incredibly striking POV cinematography and some remarkably timely commentary on the grisly consequences of urban redevelopment and gentrification.

Seven

It's possible that some of you may balk at the suggestion that "Seven" is a horror film. If that is the case, clearly we did not watch the same movie. Did you not see the opening credits sequence where John Doe, the serial killer who commits a series of grisly murders based on the seven deadly sins, shaves off his own finger prints?

Did we not experience the same guttural fear when that supposedly dead bead-ridden sack of bones ("sloth") turned out to be very much alive? Was a man being force-fed spaghetti until he died not gruesome enough for you?

With demented, contrapasso style kills that would feel right at home in the "Saw" franchise, "Seven" follows two homicide detectives (Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt) as they attempt to capture a morally self-righteous serial killer.

Directed by David Fincher, "Seven" adopts a variety of noir tropes, from incessant rain to a procedural perspective, that give the thriller a suffocatingly moody atmosphere. From hardboiled gumshoes to stark photography, "Seven" further aligns itself with the noir opus by favoring compositional tension to blood-and-guts action.

We never see John Doe commit his crimes; we merely pick through the shadow-soaked aftermath with flashlights, a notepad, and an increasing sense of futility.