These Things Happen In Every Hayao Miyazaki Movie

Hayao Miyazaki is a filmmaker without equal. This writer, director, and animator helped found Studio Ghibli, a world-renown animation studio that has created around two dozen films, many of which are some of the highest grossing movies in Japanese history.

Miyazaki himself has directed eleven films, and by all accounts, he is a truly obsessive filmmaker. According to the two documentaries that have been made about him — "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness" and "Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki" — the director ruminates endlessly about all aspects of the filmmaking process, he demands perfection from himself and everyone around him, and he has strong opinions on just about everything. Yet despite all the pain and suffering that surrounds Miyazaki's creative process, or perhaps because of it, this grumpy old man has created some of the most transcendently beautiful and joyous movies of all time.

Once you watch his entire filmography, and also learn a little about him as a person, you see all the ways in which Miyazaki's films are a direct reflection of his personality and worldview, even moreso than most directors. So today, we're running down all the recurring plot elements and thematic motifs that show up time and again in Hayao Miyazaki's filmography. Because despite his best efforts, in his words and in his movies, Hayao Miyazaki can't help being himself, and even if he could, we wouldn't want him to change anyway.

Flight

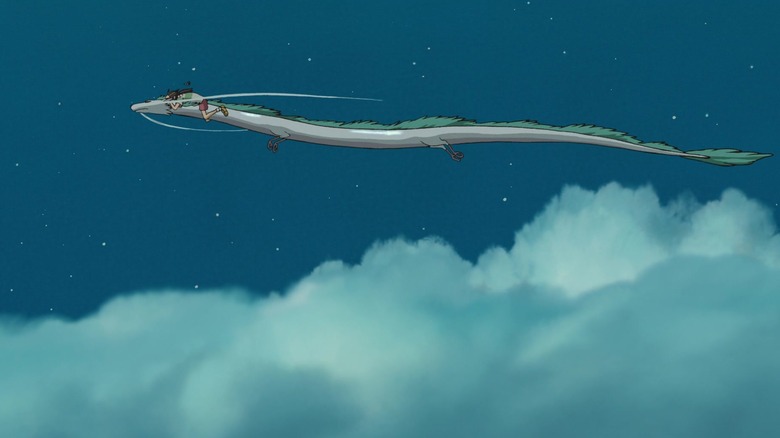

One of the most ubiquitous recurring elements throughout Miyazaki's filmography is his obsession with flight. Sometimes, his films feature actual realistic aircrafts, like the World War II-era planes in "Porco Rosso" and "The Wind Rises." Other times, they flight is totally magical, courtesy of flying broomsticks in "Kiki's Delivery Service" and flying monsters in "Spirited Away." Most films split the difference between these two extremes, featuring fantastical flying machines that are just a step beyond reality, such as Nausicaä's glider in "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" or the sky pirates' "flaptors" from "Castle in the Sky."

What's truly impressive, though, is how thoughtfully Miyazaki constructs these scenes of flight. The viewer is rarely down on the ground, watching from afar. Instead, they're over the pilot's shoulder, experiencing what the characters experience. When machines are involved, there's also an extraordinary amount of attention put into demonstrating how they function. This all helps put the viewer in the shoes of the pilot, making us feel like the ones who are actually flying.

In a way, these impossible flying machines are a microcosm of why Miyazaki's films work so well. They could never be real, but they're so thoughtfully constructed that it's easy to forget this, so we willingly take flight to a world of the fantastic, and for just a couple hours, we gleefully abandon logic, reality, and gravity.

The power of nature

Many of Miyazaki's films are about the relationship that humans have with nature, and each of his films tackle this issue from a different perspective. "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" is about the importance of taking time to understand the environment, rather than acting out of fear and selfishness. "My Neighbor Totoro" demonstrates the healing power of nature. In "Princess Mononoke," nature is so powerful that it's downright frightening, but it's also incredibly fragile and easily destroyed by human carelessness.

It's clear that Miyazaki has a great love for the environment, but his worldview is not as simple as "nature is good, humans are bad." After all, with no humans, there would be no airplanes! Yes, Miyazaki loves nature, but he also loves people and technology. When discussing environmentalism in a 1994 interview, he asserted that he would not associate with anyone who is a "fascist of ecology," and on the topic of cars, he said, "I will drive a car and cause pollution. If everyone has to stop, I'll stop, but even so, I'll continue to drive to the last."

Strangely enough, the film that perhaps best demonstrates the specific nuances of Miyazaki's environmentalist views is "Ponyo." Our plucky heroine is a magical goldfish from the natural world who falls in love with humanity. Her father, Fujimoto, hates humans unrepentantly, but he is also the antagonist of the film, and his total disregard for humanity is presented as an overreaction. The ultimate victory of the film is a union between the land and the sea, two worlds living in harmony.

Loss

On a surface level, the tone of Miyazaki's films varies tremendously, from lighthearted children's tales to somber war stories. But beneath the surface, even in his most whimsical films, there always exists an element of melancholy. This is because all of Miyazaki's films are, to one degree or another, about characters learning to carry on after experiencing loss.

In some films, this loss is palpable in every frame, as the world itself has been ravaged by widespread destruction. "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" takes place in a post-apocalyptic wasteland. "Porco Rosso" and "The Wind Rises" both depict actual historical periods of widespread warfare and death. In "Princess Mononoke," almost every character has experienced loss, and uses this as a justification to enact further violence on those they deem responsible.

Other times, the loss occurs on a more personal scale. "Howl's Moving Castle," "Spirited Away," and "Porco Rosso" all feature protagonists who have been magically cursed — stripped of their former identity and forced to live in difficult new circumstances. In "Kiki's Delivery Service," Kiki suffers the magical equivalent of artistic burnout, losing her ability to fly and her ability to communicate with her cat, Jiji. Although Kiki does regain her ability to fly by the end of the film, her ability to understand Jiji seems to be lost forever.

Even in "My Neighbor Totoro," perhaps Miyazaki's most seemingly frivolous film, is about kids contemplating the possibility that their mother may have a terminal illness. It's nowhere near as heavy as the director's more overtly tragic tales, but especially when you watch the film a second time, knowing about their mother from the very beginning, the shadow of potential loss hangs quietly over every happy scene.

The horrors of war

When it comes to the deeper meanings of his films, much of Miyazaki's work is somewhat ambiguous. His stories often deal with complex and elusive themes, where absolute truth is unknowable. That being said, there's one subject matter that, time and again, Miyazaki expresses his feelings on clearly and unambiguously, both in his films and in interviews, and that is his absolute and uncompromising hatred of war.

"The Wind Rises" and "Porco Rosso" both take place during World War II, and both feature protagonists who despise living in countries that are run by warmongering fascist regimes. "Princess Mononoke" and "Howl's Moving Castle" depict fictional wars in fantastical kingdoms, but despite their imaginary settings, combat is never shown to be glorious, and violence and destruction are never justified or sanitized.

"Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind" depicts a world that has been devastated by war, and yet the senseless fighting continues, preventing this broken world from ever rebuilding. As such, the ultimate act that our heroine takes during the climax is not to fight back, but rather to stand in the way of a stampeding army of giant bugs and allow them to trample her. In all cases, war is shown to be pointless and destructive, driven by idiotic vanity.

Given all this, whenever Miyazaki is asked about his feelings on war, he makes his position very clear. In an 1994 interview with Yom magazine, he said, "I like (reading about) war. So, people ask me such questions as 'do you like war?' I answer them 'do you think AIDS researchers love AIDS?' "

Aspirational protagonists

The first film that Miyazaki directed was "The Castle of Cagliostro," and even though Miyazaki was adapting the pre-existing character of Lupin III, his unique take on this iconic gentleman thief pointed towards the ways that this filmmaker would write many of his protagonists in future films. Though earlier portrayals characterized Lupin as a crude and selfish womanizer, Miyazaki's Lupin was a genuinely good soul, a fun-loving goofball who helps those in need. Throughout his career, Miyazaki would go on to create a wide array of iconic heroes, all aspirational figures in one form or another, with just enough flaws to keep them relatable.

Also, somewhat unusually for a male director, a surprising number of Miyazaki's aspirational heroes are female. Characters like Kiki in "Kiki's Delivery Service," Chihiro in "Spirited Away," and Sophie in "Howl's Moving Castle" are all wonderfully strong and driven protagonists, and yet the films never portray them as superhuman. We see their pain, their struggles, and their failures, which makes it all the more inspiring when they are still able to stay true to their principles in the face of adversity. And thankfully, these female heroes are rarely sexualized — at least by the standards of most anime.

No traditional villains

Hayao Miyazaki's first three movies — "The Castle of Cagliostro," "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind," and "Castle in the Sky" — all feature fairly typical cinematic villains: mustache-twirling bad guys with only a hint of humanity. However, after these three early outings, Miyazaki abandons traditional villains almost entirely and never looks back.

When a Miyazaki film does feature an explicit antagonist, they're almost always portrayed as flawed people who exist in imperfect systems. They hurt people because of their situation, not their inherent villainy. Yubaba in "Spirited Away," Lady Eboshi in "Princess Mononoke," and Fujimoto in "Ponyo" all actively oppose our heroes, but their motives are also understandable. They can be reasoned with, and sometimes their minds can even be changed.

In Miyazaki's smaller slice-of-life movies, the conflict is largely internal. In "Kiki's Delivery Service," Kiki's recurring antagonists are the daily grind of having a job, the struggles of making friends, and depression. In "My Neighbor Totoro," the primary threat to Mei and Satsuki is the looming possibility of their mother's death. It's not a problem they can fight, so instead, they spend the film processing these difficult emotions in a variety of ways — some healthy and some not.

When we do encounter actual evil in Miyazaki's later works, it comes at a scale beyond that of a single person. In "Howl's Moving Castle" and "The Wind Rises," the evil is an entire broken society, operating at a level that is beyond our heroes ability to change. Instead, they must learn to live within it. The later films of Miyazaki show us that there isn't always a single bad person you can punch to fix everything that's wrong with the world. Unfortunately, being a human is far more complicated than that.

Kids that act like kids

Although little kid characters are a fairly common occurrence in American movies, it's surprisingly rare to have one that genuinely feels like a kid. More often, when a comedic or family film features child characters, they'll be an adorably precious child, unusually mature and articulate for their age. One great thing that you can say about Miyazaki is that he stays far away from this tired old cliché. When he is telling stories about little kids, they behave like actual kids.

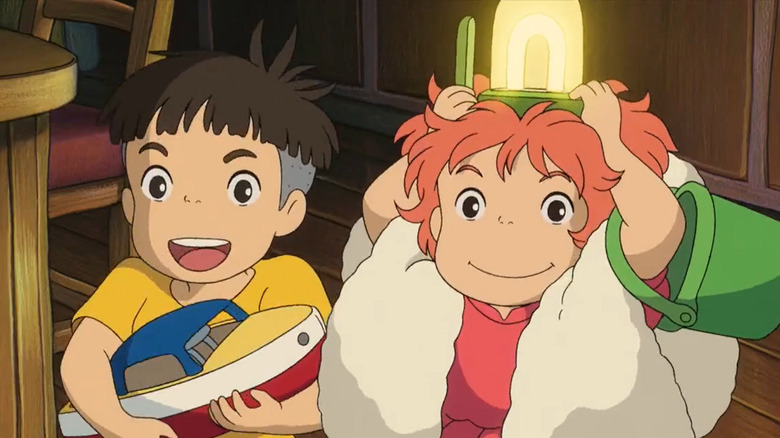

In "My Neighbor Totoro," protagonists Satsuki and Mei spend the first act of the film exploring their new home in the country. As they do so, they run around in circles, sing nonsensical songs, and scream, just like real kids who've just escaped from a long road trip. In "Ponyo," when our central pair of kids first meet, they instantly fall into both friendship and puppy love in ways that only five-year-olds can. They're overly excitable and utterly clueless, and we love them because of — not in spite of — these flaws.

Time and again, little kids in Miyazaki movies are, delightfully, all heart and no brains, constantly overflowing with enormous emotions that are too big for their tiny little bodies to handle.

Beautifully animated mundanity

In all animated films, the complexity of animation will vary from one moment to the next. Some moments will call for highly detailed and technical animation, and other moments will employ more bare bones animation, with less characters on screen, less detailed action, and less frames per second. This is the case in Miyazaki's films as well. Often the animation will be truly virtuosic, but other times it will be a bit more functional and limited. But what sets Miyazaki's films apart is that these unusually detailed, beautifully animated moments don't always come when you'd think they would, in the climactic, action-packed moments. Just as often, incredible attention will paid to characters performing mundane actions in relatively quiet scenes.

There's countless examples to choose from, but here's just a few favorites. In "Kiki's Delivery Service," Kiki pins back her sleeves with safety pins before she removes a pie from the oven. In "The Wind Rises," as Jiro rushes to catch a bus, he places a hand on top of his hat, to keep it from blowing away. In "Princess Mononoke," when Ashitaka lowers his bowl into a river to get a drink, he first dips it in once just to clean the bowl, then dips it in a second time to get a drink.

These details may sound insignificant, and in a way, they are. Had they not been included, we never would have noticed. But because they've been included, because of these occasional moments of incredibly animated mundanity, Miyazaki's worlds feel truly alive in a way that few movies can match, animated or otherwise.

Quiet moments

"Ma" is a Japanese word meaning "gap," "space," or "pause," which is used by some to artists, both Japanese and non-Japanese alike, to explain the importance of emptiness and inaction, in both art and in life. Some have argued that it's similar to the concept of "negative space" in visual arts, the idea that the empty spaces in a composition are just as worthy of consideration as the areas that contain people, objects, and action.

Explaining the concept at the 2002 Toronto Film Festival, Miyazaki said (per RogerEbert.com), "The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb."

In many ways, this philosophy stands in complete opposition to conventional Hollywood wisdom. Screenwriting books everywhere tell aspiring writers that every conversation must contain conflict, and that every moment must move the story forward. Miyazaki's movies are confident enough in themselves, and in the attention spans of their audience, that they choose to take a break every once in a while, and just show us grass blowing in the wind, or raindrops on a window, giving the audience a moment to rest, to reflect, and to exist. A well constructed plot may be engrossing, and a brilliant action scene may be thrilling, but there is also an unquantifiable power in simply watching the sunset and doing absolutely nothing at all.

Weird little critters

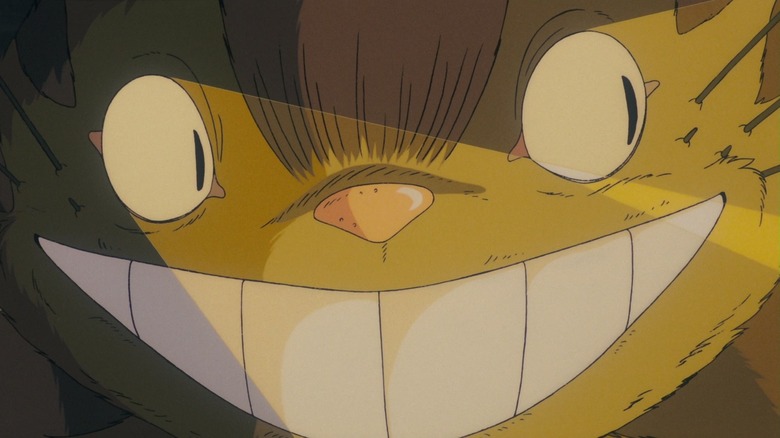

One of the most delightful recurring elements in the movies of Hayao Miyazaki are the fantastical inhuman creatures that populate his worlds. Some of these creatures are based on pre-existing entities from Japanese folklore. "Princess Mononoke" features kodama, forest spirits that each inhabit a different tree, and also the deer-headed god Shishigami (also known as Yatsuka-mizuo-mitsunu) who is worshipped in real world Japan in the Nagahama Shrine in the city of Izumo. "Spirited Away" has an entire bathhouse full of mythological creatures, including kami (venerated spirits from the Shinto religion), yōkai (more mundane and sometimes mischievous spirits), and plenty of original creations as well. In "My Neighbor Totoro," Totoro himself may be an original Miyazaki creation, but he's probably intended to be some sort of yōkai, and the Catbus is most likely a take on the bakeneko, a shapeshifting cat spirit.

A few of Miyazaki's most iconic original creatures even recur in multiple movies. The adorable little fox squirrels, first seen in "Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind," also return in "Castle in the Sky," and the sentient soot balls known as susuwatari appear in both "Totoro" and "Spirited Away." Even with characters that shouldn't be cute at all, such as No-Face in "Spirited Away," the Ohmu in "Nausicaä," and the rusted old robots in "Castle in the Sky," they all end up being strangely adorable, for reasons we can't quite put our finger on. You won't be able to help it; we want plushies of them all.

Food is love

In the films of Miyazaki, pretty much everything is drawn and animated beautifully, but the food is downright transcendent. Many of the most touching scenes in Miyazaki's movies are all about people giving food to one another, but this isn't just because the food itself looks delicious — although it does — it's because these scenes are all actually about how people connect to one another through food.

In "Howl's Moving Castle," one of the first things that Sophie does upon arriving in the castle is making breakfast for all its denizens, a key moment in her journey towards joining Howl's eclectic found family. In "Spirited Away," Haku offers Chihiro a gift of some onigiri, and though she's reluctant to eat it at first, once she gets started, she starts crying uncontrollably, clearly overwhelmed with emotion, perhaps because Haku's gift is one of the first acts of kindness that anyone has shown her in quite a while. In "Ponyo," there are two things that our titular fish princess falls in love with in the surface world that make her want to stay there forever and become a human. One is the human boy Sosuke, and the other is ham. In the language of Miyazaki, food is love.

No easy answers

Even though Miyazaki generally makes his movies with children in mind, one of the best things that can be said about his films is that they don't shy away from raising complex issues, and they never offer comfortable solutions to unsolvable problems.

In "Kiki's Delivery Service," Kiki loves flying on her broomstick, so she gets a job delivering packages. But then, she works so much that flying becomes joyless, and eventually, she can't fly at all. The film asks, "How do make your passion into a career without losing your love for it?" In "Howl's Moving Castle," Howl is an all-powerful wizard, and yet he is unable to stop a senseless war that is raging all around him. The films asks, "How are we supposed to live when terrible things are occurring that are beyond our ability to change?" In "The Wind Rises," Jiro wants to design airplanes, but he lives in a time when the only airplanes anyone wants are weapons of war. The film asks, "Is it worth it to create something beautiful, when someone else may twist your creation and use it for evil?"

Unfortunately, none of these questions have easy answers. As such, rather than resorting to old truisms and simplistic morality to answer these questions, Miyazaki often chooses to merely raise the question, and leave the answer unsaid.

The sublime

One could discuss the recurring themes in the work of Miyazaki all day — what sorts of ideas appear over and over in his movies, what they could mean, and why they're so powerful, are so powerful, but in a certain way, this in-depth analysis might be missing the forest for the trees. Listing and categorizing everything that makes Miyazaki great is arguably forgetting the larger point that much of the power in these films does not come from anything that can be explained or intellectualized.

When Nausicaä rides her glider through an endless desert, why are we left speechless? When raindrops fall on Totoro's umbrella, and this strange forest spirit shudders in delight, why are audiences not only giggling, but also enraptured? When Chihiro flies through the air on the back of Haku, why do viewers cry their eyes out? These seemingly simple scenes are all undeniable in their impact, causing an almost transcendent or religious experience in some viewers, and yet its almost impossible to articulate why.

In philosophy, this concept is known as the sublime, an encounter with something that is so great, and so beyond our understanding, that it totally overwhelms our senses, sometimes even beyond the point of beauty and into the realm of horror. Miyazaki seems to have a great respect for the beautifully enigmatic, for things beyond human understanding. As he himself put it in the documentary "The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness," "The world isn't simple enough to explain in words."