Things Only Adults Notice In Spirited Away

It would be a gross misjudgment to assume that anime is just for children. You certainly wouldn't want to plunk your kids down in front of a movie like "Perfect Blue." However, it is probably safe to assume that it's okay for kids to watch most of the films from Studio Ghibli ("Grave of the Fireflies" and "Princess Mononoke" excluded). This animation studio has produced several family films like "My Neighbor Totoro" and "Kiki's Delivery Service" and is known for its gentle and wholesome aesthetic.

"Spirited Away" is one such movie. After all, director Hayao Miyazaki created the movie with children in mind. Miyazaki was inspired by a real-life girl to make a movie that would appeal to 10-year-old girls. However, "Spirited Away" is much deeper and darker than your average family-friendly film, ensuring that there is plenty for adults to appreciate. The film's mature themes of consumerism and workplace harassment might go right over kids' heads. In addition, one iconic scene might even force viewers to confront an uncomfortable truth about adulthood. These details from "Spirited Away" will give adults in the audience a lot to think about.

Chihiro's parents are pigs in more ways than one

Any kids watching "Spirited Away" will watch the transformation of Chihiro's parents and take it at face value. Her parents were acting like pigs, engorging themselves on food that wasn't even theirs, so naturally, they got turned into pigs. However, the scene in "Spirited Away" means more to fans than you'd think. There is a whole other layer to the pig metaphor.

The key to understanding this subtext is something Chihiro's father says when he first enters the realm of spirits. "It's an abandoned theme park," he concludes. "They built them everywhere in the early '90s. Then the economy went bad and they all went bankrupt." According to Cal State University student Penelope Yagake, this is a reference to Japan's bubble economy, which expanded rapidly in the 1980s and brought short-term prosperity, only to collapse in the early 1990s and plunge Japan into a recession.

Miyazaki intended for Chihiro's parents to embody the rampant materialism of that era. After all, they are indulgent and heedless of consequences. They assume it's fine to take the food without getting permission from the owner. "We can pay the bill when they get back," says Chihiro's mom, which is symbolic of the "eat now, pay later" mindset that caused the economic bubble to burst. In a reply to a fan letter (translated by Sora News 24), a representative of Studio Ghibli explained that Chihiro's parents are becoming pigs in the same way that many people became pigs during the bubble economy.

Yubaba embodies Westernization

Chihiro's parents aren't the only characters who represent a corrupting influence on Japan. Blogger Amanda Actually points out that Yubaba embodies the West. Her Victorian-style clothing, the pipe she often smokes, and her preoccupation with profit all seem more European or American than Japanese. Yubaba takes something that is traditionally Japanese (a bathhouse) and then Westernizes it by turning it into a for-profit operation, complete with Western technology (like Kamaji's industrial boiler room) and Western infrastructure (like foremen who would seem more at home in a Western factory than a traditional bathhouse). Yubaba runs a system where everybody needs to get a job to survive, which seems as alien to Chihiro as the Western capitalist system must have seemed to the Japanese when Westerners first began to exert their influence in Japan.

When Yubaba imposes her Western values on everyone at the bathhouse, the characters begin to forget who they are. Some critics, including Cal State University student Penelope Yagake, argue that the film can be read as a metaphor for Westernization threatening to erase traditional Japanese culture. Just as Chihiro and Haku must fight to keep Yubaba from stripping away their identities, many Japanese people feel like their identities are eroded by Western influence.

The movie's slow pacing is intentional

"Spirited Away" clocks in at a lengthy two hours and five minutes, and not all of that time is spent advancing the plot. The film often lingers, taking its time to absorb Chihiro's surroundings or focus on a character's face. For instance, one sequence spends two-and-a-half minutes just on Chihiro inching her way down a winding staircase and peeking into the boiler room, while other filmmakers might have simply skipped ahead to Chihiro in the boiler room. Miyazaki certainly likes to take his time.

The pacing of "Spirited Away" may occasionally make kids antsy, but adults will appreciate this artistic choice. By taking things slow, the movie allows complicated emotions to sink in and gives the characters breathing room, explains Loud and Clear. "If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness," Miyazaki told Roger Ebert in an interview. "But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension." Miyazaki added that he was trying to capture something that the Japanese call "ma." According to Miyazaki, "ma" refers to emptiness or the space between two things. In his films, Miyazaki uses "ma" as an intentional effect to immerse viewers in the story. In the case of the scene where Chihiro descends the stairs, this seemingly insignificant moment is important for conveying the vastness and the strangeness of the world that she feels totally unprepared to navigate.

Chihiro is experiencing workplace harassment

After Chihiro and Lin have been assigned a near-impossible task by Yubaba, Lin throws down her sponge and declares, "This is clearly harassment!" It's no secret that Yubaba treats her workers unfairly, but many kids may overlook the movie's real-life parallels. Adults who have experienced workplace harassment, on the other hand, will find Chihiro's experiences all too familiar.

The other bathhouse employees discriminate against Chihiro because she's a human. In fact, right from the start, Yubaba is setting up Chihiro to fail. She assigns Chihiro the filthiest tub and the stinkiest customer. When Chihiro asks for a herbal soak token to complete her assigned task, the foreman refuses to give her one and tells her, "Scrub it yourself" –- no matter that he hands out these same tokens generously to customers. Once the stink spirit arrives, Yubaba urges Chihiro to "take the nice customer's money" (an unpleasant task that involves getting up close to the stink spirit and receiving a handful of sludge) even though Yubaba is perfectly capable of doing it herself. Chihiro's boss wants to take credit for greeting the customer personally, but she delegates the dirty work to her underlings. Worst of all, Yubaba positions herself on the mezzanine above the stink spirit so she can watch Chihiro get humiliated.

All of these are situations that real-life workers can relate to, which lends authenticity to the movie and ensures viewers will root for Chihiro. So it's all the more satisfying whenever Chihiro beats Yubaba at her own game.

Chihiro isn't the only one impacted by toxic work culture

When it comes to dealing with the unhealthy working environment of the bathhouse, Chihiro isn't alone. Everyone in the bathhouse is affected because Yubaba puts profit over employees. For instance, Yubaba is much more concerned about the financial damage No-Face has done than the people he has swallowed. Viewers will notice that Lin is in the same boat as Chihiro. She is forced to clean the big tub along with Chihiro, and she too dreams of someday getting out of the bathhouse, though the movie suggests that Lin is so deeply entrenched in her way of life that this dream will always be out of reach.

Kamaji may seem at a glance to be an uncaring supervisor who works his soot spirits to exhaustion. However, Yubaba has taken her toll on him, too. CBR points out that Kamaji is under a lot of pressure from Yubaba to circulate hot water around the bathhouse, which is why he unfairly takes out his frustration on the soot spirits. Even Yubaba's henchman Haku is impacted. Haku is Yubaba's favorite and the others resent him for it, which leaves him with no friends whenever he falls from Yubaba's favor. Both Haku and Lin are shown to code-switch; they act cold toward Chihiro whenever Yubaba is nearby, but then show a more supportive side when they're sure Yubaba and her cronies are out of earshot. CBR concludes this is a behavior they've adopted in order to survive in the workplace.

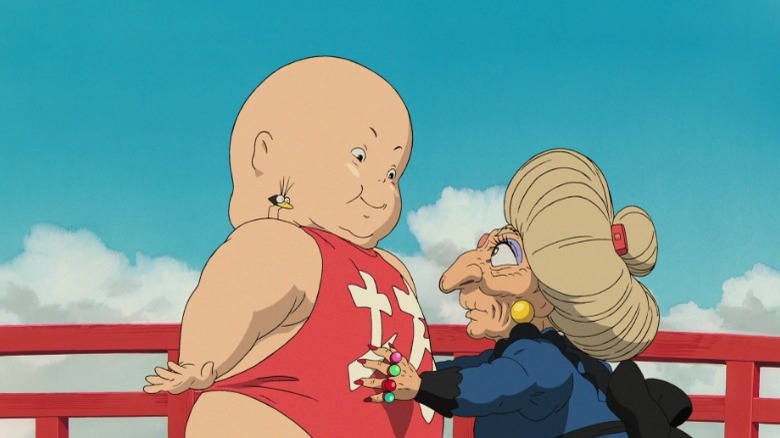

Yubaba is an overprotective mother

At a glance, the scenes with Yubaba and her son Bôh seem absurd. Kids may laugh at the strangeness of a gigantic baby who is bigger than his mother. Parents, however, will notice that the scenes with Yubaba and Bôh are actually grounded in reality.

Yubaba is clearly spoiling her son. She picks up his toys for him and gets him whatever he wants. She manipulates Bôh by telling him that the outside world is teeming with germs, and she pampers Bôh in hopes that he'll never want to leave. Yubaba paints the walls with a fake pastoral backdrop, gives him practically every toy ever, and smothers him with love because she's terrified of the inevitable moment when Bôh won't need her anymore.

Yet Yubaba is wrong — she's actually holding her son back. Chirio tells Bôh "staying in this room is what will make you sick." Cal State University student Penelope Yagake argues that sheltering your children too much will make it harder for them to survive on their own, adding that the dynamic between Yubaba and Bôh is a perfect example of this. Only when he is free of his mother's smothering influence does Bôh begin to grow. When Yubaba is finally reunited with Bôh, she is surprised to learn that he can stand on his own, just as Chihiro learns to survive without her parents.

The bathhouse could be read as a metaphor for the sex industry

Some fans have pointed out an eyebrow-raising theory about "Spirited Away" — one that is definitely not appropriate for kids.

It's possible that the bathhouse is encoded as a brothel, and Chihiro's journey could be alluding to the experiences of women in the sex industry. This interpretation shouldn't be surprising. As CBR explains, many bathhouses actually were brothels during Japan's Edo period. In "Spirited Away," one sign outside the bathhouse reads "hot water." This could be a reference to "hot water women," the name given to Edo-era sex workers. Also, Chihiro must change her name, not unlike the way many sex workers adopt stage names. This theory may seem a little far-fetched, but who knows? After all, the bathhouse customers all appear to be male, points out Studio Ghibli Movies. One such customer is No-Face, whose actions take on a whole new meaning if you look at the movie through this lens. You'll notice that No-Face tries to buy Chihiro's trust with things he assumes she likes, which is reminiscent of a tactic that pedophiles often use.

Of course, Miyazaki almost definitely didn't intend the movie this way. Since the director's whole reason for making "Spirited Away" was to create a movie for 10-year-old girls, it follows that the very adult subject of the sex industry probably wasn't in his plans. Nevertheless, fans still may have trouble un-seeing this theory.

Certain nuances are lost in translation

Those who compare the Japanese and English versions of "Spirited Away" will get a deeper meaning from the movie. The Japanese version contains some lingual wordplay. According to The Otaku, many of the meanings behind character names are lost in translation. For instance, Kamaji's name is derived from the Japanese words for "boiler" and "old man." Likewise, Yubaba's and Zeniba's names translate to "bath grandmother" and "money grandmother," respectively. Most notably, Chihiro's assigned name "Sen" can be translated to mean "one thousand," meaning that Yubaba is essentially reducing Chihiro to nothing more than a number.

Also, the Japanese version has Zeniba refer to Yubaba as "imouto," a word that means "younger sister." Even though the two sisters are canonically twins, using a word with this connotation adds another layer of meaning to their relationship. The Otaku argues that Yubaba views Zeniba as an annoying older sister and perhaps might even be jealous of her.

Translator Dr. Jonathan Clements pointed out in an interview with the BBC that the scene in which Chihiro and her parents wander through the ghost town is even more intense for Japanese-speaking viewers because they will be able to read some of the signs in the background. Japanese audiences will notice that there's something a little bit off about each sign. For instance, says Clements, what appears to be an optician is actually "an 'eyeball shop', and it's even advertising 'fresh ones' just in." These signs only amplify the feeling of dread.

The motif of eating and vomiting has a deeper meaning

Watching "Spirited Away," you may notice that there are an awful lot of scenes that involve eating or vomiting — or both. Chihiro's parents stuff their faces while No-Face eats anything he can get his hands on. Yet by the end, No-Face barfs everything back up again, while Haku coughs up the seal he swallowed. What's up with that?

Plain Flavored English argues that all this eating and vomiting imagery is there for a reason. There's a clear pattern: All the characters who eat voraciously undergo an unpleasant transformation (like Chihiro's parents or No-Face), while the characters who purge something from their bodies end up returning to their true selves. For instance, No-Face shifts back to his original form once he is done spewing, and Haku needs to regurgitate the seal before he can break free from Zeniba's curse. Even the stink spirit vomits, in a sense, whenever Chihiro yanks the trash from its body and allows it to become a river spirit again.

Plain Flavored English posits that this motif is a commentary on consumerism. In a consumer culture, we consume things hoping to find meaning or a sense of belonging, whether we are literally consuming food or figuratively consuming material goods. But of course, all these objects can't fill the void in our souls, just as the things No-Face swallows can't satisfy his need for an identity. Perhaps Miyazaki is saying that we need to purge ourselves of material "things" in order to discover who we are.

Chihiro is constantly expected to be a grownup

Anybody could tell you that "Spirited Away" is a coming-of-age story. But it's interesting to note that Chihiro is repeatedly forced to step up into the role of an adult whenever the real adults fail her.

The most egregious failure comes from Chihiro's parents. Although they ought to be protecting their daughter, they drag Chihiro into the realm of spirits, despite Chihiro's insistence that it's a bad idea. In a startling reversal of roles, it is the kid who must tell the grownups that they can't just take whatever they want. And after her parents transform into pigs, Chihiro is the one who must save them. She must get a job in order to survive, something that many young adults first striking out on their own can empathize with. Once she starts work, Chihiro is unfairly held to the same standard as adult women, even though she's only a kid and it's her first day on the job, observes Study Corgi.

For much of the movie, Chihiro is cleaning up other people's messes, whether she is returning the seal to Zeniba on Haku's behalf or dealing with No-Face when all the other adults refuse. While it's true that Chihiro was the one who let No-Face into the bathhouse, the other characters are also guilty of feeding the spirit. The fact that Chihiro is taking responsibility for her own actions — and everybody else's — shows how much she has matured.

The shadowy passengers on the train represent adulthood

Fans agree that the train scene is by far the best scene in "Spirited Away." Still, there's one thing the movie never explains: Who or what are the ghostly figures riding the train?

One theory, according to Film Daze, is that these are all people who have lost their spark to the drudgery of adulthood. Specifically, says Krispiness, it may be a reflection of one particular aspect of adult life: work. Adults will notice that many of these passengers carry briefcases and look like they're making a long and weary commute to work. Perhaps they have all signed away their souls to their jobs, and their work has drained all their energy until, little by little, they have faded away. Maybe this scene is expressing what happens to everybody whenever they grow up — they become empty shells.

Chihiro's decision to board the train marks a key step forward in maturity since she is venturing into the unknown to help her friend Haku. Arguably, this is the moment Chihiro finally becomes an adult. She knows it's a one-way trip, yet she does it anyway. Fittingly, becoming an adult is also a one-way trip. However, it's worth noting that Chihiro doesn't fade like the other passengers, and she ultimately makes it home okay. Perhaps that's a sign that she has learned to survive the adult world without losing her innocence.