The Ending Of Tár Explained

The following article discusses sexual abuse and suicide. If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

It's been more than 15 years since Todd Field's last movie hit theaters. Needless to say, a lot has happened in the interim. Field, a mentee of Stanley Kubrick, has previously used his films — 2001's "In the Bedroom" and 2006's "Little Children" — to explore tangled domestic relationships. With 2022's "Tár," Field turns his lens toward tangled professional relationships. Of course, all relationships, including the ones we form at work, are personal, and that's at least part of the film's point. The worst executives and luminaries didn't only start abusing their power in the last decade and a half — it's just that we've only started to have public conversations that reckon with that fact in person, online, and in our art.

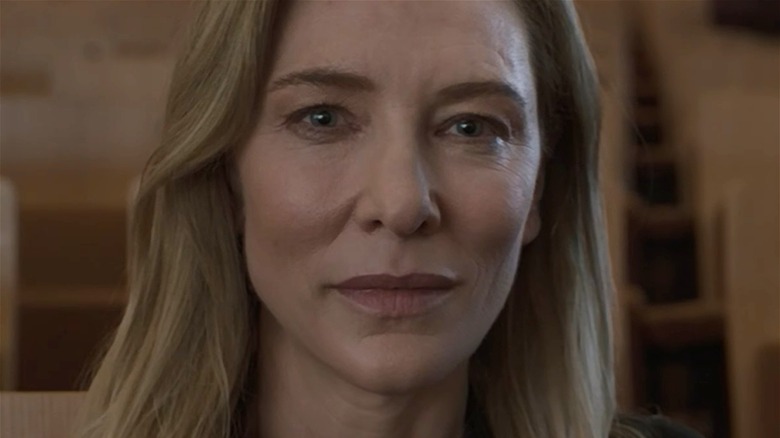

Field is also a musician (as well as an actor), and he sets this timely psychological drama in the elite world of classical music. This particular world is already so high-strung it's been the setting for similar psychological dramas. However, "Tár" shows us that world not from the perspective of the stressed-out ingenue but the accomplished master slash monster, the titular Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett). The story of the woman with the baton is thorny and largely unresolved, and it asks more questions than it answers.

Lydia Tár is at the apex of her career

When we meet Lydia Tár, she's taking one last deep breath before walking on stage to participate in The New Yorker Festival, where she's being interviewed in front of a live audience by the magazine's famed staff writer, Adam Gopnik (as himself). Gopnik enumerates the many feathers in her cap. She's an accomplished pianist and composer. She's an expert in the music of Peru. She's one of only 15 EGOTs. Leonard Bernstein was her mentor. She's held enviable positions at music institutions all across the globe and is finally about to record Mahler's 5th symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic, her current employer, which will complete her own cycle of the composer's work. It should be noted that the use of Mahler as a source of inspiration for Lydia is symbolic on various fronts, as we'll get into down the line.

Lydia is also about to publish a book, "Tár on Tár." That she's achieved enough to be worthy of a career retrospective at a relatively young age shows us just how celebrated a figure within a rarified world she is. So do shots of her expensive custom shirts being hand cut and sewn, as well as early scenes in which those in her orbit (her assistant, Francesca, and her business partner, Eliot) fawn over her. However, the way Gopnik asks and Lydia answers questions — as if they both automatically assume that everything she says is brilliant — is the biggest clue that this high-horse riding anti-hero is ripe for an epic fall.

She's not exactly an ally to the disenfranchised

While in New York, Lydia gives a guest seminar for students at Juilliard. In a prolonged single-take sequence that doesn't reveal its point until the end, the maestro fast talks to a nervous "BIPOC pangender person" named Max who says that they aren't interested in the old masters like Bach.

Max is a straw character for woke identity politics, and they think the Bachs of the world have already gotten enough attention and that the next generation isn't obligated to interpret their "intent" (a favorite word of Lydia's) if they perceive that intent to be bigoted or exclusionary. The visiting professor first suggests that if Max can reduce Bach to his superficial identity, then anyone could just as easily reduce Max to Max's. Then she humiliates him in front of his peers until Max curses at her and storms out of the room.

Lydia is trying to have her intellectual cake and eat it, too, throughout "Tár." She calls herself a "U-Haul lesbian" while she picks apart identity politics. During her New Yorker interview, she's dismissive of the idea that there's anything special about the fact that she's the first female chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. She gives lip service to the women who came before her, but Lydia's commentary on gender, sexuality, and her profession in the first half of the movie shows her as the type of woman who pulls the ladder up behind her — unless she can use that ladder to her advantage.

She's a bully and a liar

The audience's first impression of Lydia Tár might vary from admiration (she is very cool and successful) to annoyance (she is also really full of herself and pretentious). Viewers — especially those who enjoy classical music and Cate Blanchett — might even be lulled into liking the character. Still, "Tár" signals that we're not supposed to like her, or if we do, we're supposed to like her despite our better judgment, as might be the case with her wife, her assistant, and the other sycophants in her circle of influence. We get evidence of her toxicity in nearly every exchange she has with another person, save for that stagey New Yorker interview.

It's clear from the start that Lydia is blacklisting Krista and misrepresenting their relationship to Eliot and Francesca. When Sharon asks why she didn't answer the phone, Lydia tells her wife not to be a "scold." Worse yet, she lies and manipulates without remorse.

However, one conversation stands out as especially foreboding. Sharon confides in Lydia that she's worried about their daughter, Petra, who comes home from school with bruises. Lydia finds and confronts the bully. On the surface, a parent's instinct to protect their offspring is a virtue, but the power differential between an adult and child combined with the way Lydia intimidates her is seriously problematic. She threatens the girl and tells her if she ever speaks up, no one will believe her. This is grooming and primes the audience for what comes next.

She takes an interest in a cellist named Olga

During rehearsals, Lydia's eyes frequently pause on a young Russian cellist named Olga. She isn't even officially a member of the Berlin Philharmonic yet, but the conductor seems taken with her and her playing. Lydia researches Olga online and discovers a YouTube video of her playing Edward Elgar's Cello Concerto as a teenage prodigy. Knowing Olga is familiar with it, Lydia announces to the company that they'll perform the concerto as the companion piece to Mahler's 5th. She also makes the unorthodox decision to hold auditions for the solo rather than to give it to the first chair cellist, as is the custom. Only two cellists agree to participate in the audition, and Olga is chosen and given a permanent job, just as Lydia intended.

Lydia begins inviting Olga to her home to practice and accompany her on trips. At first, the girl is bubbly and grateful in her mentor's presence. However, Lydia, who's used to these kinds of transactional relationships going her way, begins to see that this time she's the one that's being used. On a trip to New York, Olga feigns jet lag to avoid going out to dinner with her boss. When Lydia later catches her getting into the elevator dressed up for a night on the town, she tries to follow her through an abandoned housing unit before falling and falsely blaming the injuries on a made-up attack. Olga is further proof that Lydia has trouble with the truth and abuses her power.

An assistant conductor makes an accusation

Lydia's treatment of her assistant conductor, Sebastian, is similarly informative. Projecting, she questions his professionalism to Eliot, who suggests exactly what she wants — she should rotate him out of Berlin. When she makes a move, she intends to give his job to her assistant, Francesca. It's ambiguous whether Lydia and Francesca are or were romantically involved, but Sebastian (knowing he's being let go) puts things more plainly than the rest of the movie does when he assures her that everyone knows she has favorites. People are aware that she trades promotions for sexual favors and that she likes pretty young girls. He correctly assumes she's planning on putting Francesca in his place, which forces Lydia to deny this and name someone else.

Sebastian doesn't seem to realize that Lydia's moved on to Olga, but calling her out causes the rift that leads to Lydia's comeuppance. Importantly, he doesn't focus on Francesca. Instead, he points out a pattern he's witnessed in the seven years Lydia's been at Berlin, one in which he's acknowledging he's been complicit with his silence. We're left to wonder if Lydia and Sharon's marriage began this way when Sharon describes how they had a hard time going public. Later, she accuses Lydia of only ever having one relationship in her entire life that wasn't transactional — the one between her and her daughter. This episode demonstrates that Lydia treats everyone this way and that her supposed genius has provided her with ample enablers.

A former fellow commits suicide

As fascinating and frustrating a person as Lydia Tár is, much of the film seems like a confident if ambling character study. Then the plot comes crashing in.

Lydia and Eliot have set up a fellowship program designed to help level the playing field and promote more women into conductorships. They brag to each other about how they've successfully placed all but one of their graduates. Krista Taylor's parents have contacted Eliot to complain that she hasn't been able to find work despite her stellar performance. Krista herself is emailing Francesca, who tries to get Lydia to take her growing desperation more seriously. However, Lydia insists that Krista is a strange girl who simply isn't one of them.

When Lydia's out running, she hears screams but can't trace them. Shortly after, Francesca informs her that Krista has committed suicide. Her assistant breaks down, feeling responsible. Again, Lydia derides the victim and protects herself. Then, in flashes of haunted memory, we see that Lydia did have a predatory sexual relationship with Krista that somehow went awry. The movie hinges on the fact that the title character ignored Krista's pleas and, no matter how hard she tries, can't control the fallout.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Her partner and protégé have had enough

When Lydia passes over Francesca to save face after her confrontation with Sebastian, she deals her career a fatal blow. Francesca resigns and begins cooperating with the investigation into Krista's death. Her parents are suing Lydia, and a scorned Francesca is happy to supply them and their lawyers with all the information they need to make their case. She didn't delete the damning emails as her former boss — and perhaps lover — ordered, which outline Lydia's abuse of the girl and the extent to which she defamed her within the music world to keep that secret. Lydia tries her old tricks with the board, her agents, and her lawyers to little avail. Her defense — that the girl was obsessed with her — doesn't hold much water.

In the wake of the now-public scandal, Sharon leaves with Petra. Their last fight strongly implies that Sharon's always been aware that Lydia cheats. She accepted that Lydia brought Olga to New York with the expectation of sex (Lydia, who cannot be wrong or show humility, yells she just needed someone to carry her bags). Sharon is angry that Lydia didn't prepare their family for the coming storm. Even if Lydia can't be faithful, Sharon at least wants her famous and lauded wife to respect her enough to tell the truth and ask her opinion. Seeing that she'll never get that kind of mutual respect and honesty, she ends things for good.

Lydia's bad behavior catches up to her

At least some people who watched "Tár" knew it involved a famous figure being canceled. Those viewers surely waited with bated breath through all of Lydia's awfulness for the other shoe to drop. However, Lydia isn't canceled overnight because of a trending hashtag or viral video. Yes, her ill-advised rhetorical flourishes at Juilliard get deceptively edited into a YouTube clip that makes the rounds and makes her look less polished and intelligent — but just as callous as she was in the moment. Yes, Gen Z protestors with cardboard signs accost the limo outside her doomed book signing. Still, none of that is what ends her career.

It isn't a single other shoe that drops, it's just that the people in her inner circle all come to the same realization at around the same time. Olga rebuffs her advances. Francesca quits and turns on her. Sharon takes off with their child. More stories come out. Her agent drops her. The Berlin Philharmonic — unconvinced by her side of the story — removes her as chief conductor. They may have been aware of the kind of monster she was, but they were just willing to put up with it for the benefits of being associated with a genius.

Once her sins come to light, nobody wants to be associated with Lydia anymore because all her relationships are strictly transactional and controlled. There's no benefit to being with a monster, personally or professionally, once everyone knows they're a monster.

She makes a spectacle of herself

In its opening scene, "Tár" tells us what Lydia's entire career has been leading up to — she's about to conduct Mahler's 5th, the last of the Austro-Bohemian composer's pieces which she has yet to record with the Berlin Philharmonic. That she loses her job just before this performance is scheduled to take place is either delicious just-desserts or bittersweet irony depending on how sympathetic one finds Lydia. However, the way in which Field relays this information to the audience is one of the film's best surprises.

We see Lydia dressing in stiff whites and blacks. She breathes in and out ritualistically, as we've seen her do before when she's about to take the stage. Then she runs aggressively down the aisle of the theater and body slams Eliot, who we suddenly realize has been hired to fill in at the last minute. That she's been replaced by the man she considers to be beneath her talent-wise and who dared to cut ties with her is apparently too much for Lydia to endure. The players, including her estranged wife, look on in horror and embarrassment as Lydia is hauled away by security.

Again, this extreme outburst can be interpreted differently depending on how sympathetic one finds the protagonist. Perhaps it's a statement that Lydia is unwell and suffering from mental illness or personality disorder. Or, perhaps she's an irredeemably self-obsessed, destructive person. These two possibilities aren't mutually exclusive. The larger point is, canceled or not, Lydia just body-slammed whatever slim chance she had at a comeback.

A visit home tells us who she really is

Everything in Lydia Tár's life is painstakingly curated to maintain and preserve her mythical reputation. Her appearance, her apartment, her mannerisms, and her food choices are all a living museum to a constructed persona. We find out just how much of a creation that identity is once Lydia has lost everything and has to return home to Staten Island. She pulls up in front of a mid-century working-class house and ventures inside. Her brother is waiting, and he says in a thick accent that their mother mentioned she might be stopping by. There isn't much warmth in his voice, which suggests there isn't much love between Lydia and her sibling.

This quick and humbling visit home reveals a little (though purposefully still not much) about Lydia's backstory. She's actually Linda Tarr. Somewhere along the way, she changed her first name and altered the spelling of her last name to give herself more of an upper-class aura. That she changed her accent and doesn't at all embrace her blue-collar roots was likely taken as a rejection by her family. Figuratively speaking, Lydia tried to get as far away from her childhood as possible.

Whether her family rejected her interest in music (or women) first or whether she was also emotionally abusive to her family members, we can't know. However, as "Tár" winds down, it's clear that she's made herself unwelcome both at the home she was born into and at the one she made with Sharon and Petra.

She restarts her story

The final scene of "Tár" is a jarring tone shift but also a fitting resolution to the plot. After taking a guided tour of Tokyo, Lydia is preparing to conduct musicians again. She recites her now-familiar talking points about a composer's intent, and the players begin to play. Fans of the "Monster Hunter" video game series might recognize the melody, as she's found work leading the "Monster Hunter" orchestra, which is performing in front of a live studio audience populated by enthusiastic cosplayers.

Just prior to leaving for Tokyo, Lydia met with a new talent agency. She couldn't secure representation with their top-tier management, but an eager young gun was willing to take her on. He advised her that she needed to restart her story. It's a euphemism for accepting that she's been knocked down many pegs and will have to start from the bottom if she ever hopes to work her way back up to stardom, acclaim, and social acceptance again.

The conclusion is admittedly silly but still thought-provoking. Despite her possible crimes — the case against her seems to be ongoing — she's still getting to do what she loves, and what she's doing is still making people happy. It's only a fall from grace if she snobbishly turns her nose up at video game scores. Still, keep in mind that we also see throughout the film that she only has one take on interpreting classical music, which could indicate she was never that much of a genius but just a talented work-a-day conductor like so many others around the world.

Comparisons to Mahler

Let's return to the biography of Gustav Mahler. At one point, Francesca and Lydia get into a lighthearted spat about him. Francesca tells Lydia that she disagreed with her New Yorker comments about the composer's marriage and how it influenced his compositions. In particular, Francesca doesn't think Mahler's wife, Alma, should've had to put her music career on the back burner just because she was wedded to a supposed genius. There's an obvious parallel here to Lydia and how she forces the people in her life — romantic partners especially — to take a back seat to her success. However, there are more parallels between Mahler, the fictional Lydia Tár, and the movie itself.

Mahler was born to a Jewish family and faced anti-Semitism. He even converted to Catholicism to secure positions. This mirrors Lydia's gender, sexuality, and efforts to other herself as little as possible to get ahead in her chosen profession. Mahler also had a reputation for scandalizing young women who yearned to sing in the opera, one that his wife Alma (19 years his junior) was aware of. He had an abusive father, suffered from mental illness, and had a tic in his right leg, which calls back to the Juilliard scene. He passed away before he finished his 10th symphony, while Lydia becomes persona non grata just before she can complete her performance cycle of his work.