The Dark History Of Carrie

There have been a lot of incredible female horror villains over the years, but female characters who are both victim and villain — who get our sympathy and pity even as they eventually terrify us — are still comparatively rare.

The exception is Carrie White, the lead character from Stephen King's first novel. Carrie grabbed horror fans' attention, and we've never gotten tired of her. The book has gotten several relatively faithful adaptations – the Academy Award-nominated 1976 film, directed by Brian De Palma and starring Sissy Spacek; the 2002 TV movie, directed by David Carson, written by genre favorite Bryan Fuller, and starring Angela Bettis of "May"; the 2013 update directed by Kimberly Peirce and starring Chloë Grace Moretz; and even an ill-advised musical — and the sight of a blood-soaked Carrie in her prom dress has rightly become iconic.

We keep coming back to this story because Carrie herself is so compelling. In a lot of ways, she's the quintessential underdog — bullied, ridiculed, and abused — and we want to see her embrace her telekinetic powers and stand up for herself. When we get the darkest possible version of that, it's as unforgettable as it is horrifying. So we have to ask: How did Carrie get to that point? What events, in reality and in fiction, made her who she is?

'Carrie' originally landed in the trash

Stephen King was a struggling high school teacher when he sold "Carrie," his first published novel. In his memoir "On Writing," King describes the seismic impact the book's success had on his life. The sale of its paperback rights — for a then-astronomical $400,000 — single-handedly lifted him and his family out of grinding near-poverty. It kick-started an acclaimed career that made him the face of horror literature and one of the most famous living novelists, period.

And it almost didn't happen, because he wrote the first couple of pages, looked them over, and tossed them straight in the trash. He didn't feel like he had the expertise to write something immersed in the world of teenage girls — at least, he doubted he could write it naturally and comfortably — and on top of all that, he could already see that the "short story" about Carrie White would need to run longer than magazines usually accepted.

It was his wife, novelist Tabitha King, who fished the early pages of the manuscript out of the trash and told him that regardless of his concerns, he should keep working on it, adding: "You've got something here ... I really think you do." King wryly concluded that she was right, and he "did have something there. Like a whole career."

Carrie was modeled after two girls Stephen King knew in high school

In Stephen King's memoir "On Writing," he writes about how he drew on "the two loneliest, most reviled girls in [his high school] class" to create Carrie White.

"Sondra" was a friendless girl whose fanatically religious mother helped inspire Margaret White. Like Carrie, she grew up in the shadow of an immense and gory rendering of a crucified, suffering Jesus. The sight left a huge impression on King, who wrote that this image "undoubtedly played a part in making her ... a timid and homely outcast who went scuttling through the halls of Lisbon High like a frightened mouse."

Sondra's counterpart was "Dodie," whose humiliating high school experience provided a tragically vivid example of how horrifying teenage bullying could get. The child of eccentric and neglectful parents, Dodie was forced to go through over a year of high school wearing the same clothes day in and day out ... but the worst of the bullying actually happened when she returned from winter break with new, much more fashionable clothes. King reports that Dodie's brief attempt to better herself was met with harsher criticism than ever, and her spirit quickly wilted in response.

This real life inspiration makes Carrie's misery feel grounded and all too real: It's a grim, plausible starting point for a story that will end with telekinesis and bloodshed.

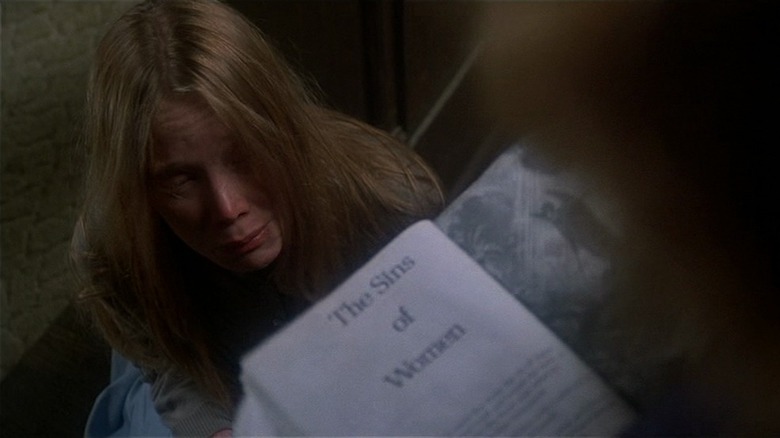

Margaret White's religious fanaticism shaped her daughter's whole life

Carrie grows up in a rigidly religious household governed by her mother's harsh and severely skewed view of Christian doctrine. It's notable that Margaret White is such an extremist that she can't find any church that meets her exacting and oppressive standards for holiness; any church outside her home is "doing the work of the Antichrist." Her house is decorated almost exclusively with religious art picked to emphasize judgment, suffering, and anger, and the massive plaster crucifix used to give Carrie nightmares.

Margaret White doesn't limit her fire and brimstone speeches to "traditional" sins, either: She has a whole laundry list of ordinary, innocent comforts and pleasures that she believes are evil. Showers, pillows, and the color red are all sinful and forbidden.

Most damaging of all, however, is the fact that her fanaticism convinces her that the natural biological process of puberty is a sign of sin. She convinces a young Carrie that "good girls" don't get "dirtypillows" (her term for breasts), and she doesn't tell Carrie about the "sinful" existence of menstruation at all, leaving Carrie completely blindsided and terrified when she gets her first period in the shower at the school gym. Margaret is definitely one of the creepiest and most damaging fictional parents.

Carrie's mother almost killed her when she was a child

When Margaret White tries to murder her daughter on prom night, only Carrie's telekinetic powers save her ... but that's the last time she almost dies at her mother's hands, not the first. Carrie's mother tried to kill her three times before: Once when she was born, once when an infant Carrie first showed evidence of telekinesis, and once when Carrie was three and dared to talk to her sunbathing neighbor.

Mostly, Margaret's attempts on her daughter's life aren't really about her terrifying abilities: They're about what she thinks of as sin, both her daughter's and her own. She's convinced that any sex, even within marriage, is horribly sinful, and she believes that Carrie's birth was her punishment from having "sinned" with her husband. At the end of the novel, she tells Carrie that she originally planned to kill her at birth: "When the pains began I went and got a knife ... and waited for you to come so I could make my sacrifice. But I was weak and backsliding."

Right up until her own death, Margaret truly believes that murdering her daughter is the right, moral thing to do — to expiate her own sin, to prevent a budding source of terror, and to punish Carrie for even the faintest hint of sexual awakening. That certainty makes her one of Stephen King's scariest villains.

When she was a toddler, Carrie unconsciously caused stones to rain down on her house

One of the earliest and most public signs of Carrie's telekinetic powers comes when she's three years old.

Carrie's teenage neighbor Estelle is sunbathing in her backyard in a bikini, and the three-year-old Carrie — then a sweet, pretty little girl — comes over to talk to her. That's all it takes to incite her mother's fury. Margaret White is so appalled at the "sinfulness" of Estelle's bikini and so horrified by Carrie's obvious reluctance to come home that she starts tearing at her face with her fingernails, hurting herself to drive Carrie back to her.

She gets Carrie back in the house, but that's not the end of the story. Soon, enormous hailstones begin raining down on the Whites' property, followed by a cascade of actual stones. The showering of stones — including huge chunks of granite — wreck the White house, but leave everyone else's property undamaged.

It's a vivid illustration of Carrie's bottled-up hatred of her mother and her home, and we eventually find out that it was caused by more than just Margaret's usual abuse: It was actually Carrie's way of protecting herself when her mother tried to murder her. It's unsurprising that this reflexive desire to use her talent to protect herself, both physically and emotionally, would later come back in a much more tragic form.

Carrie's peers bullied her relentlessly

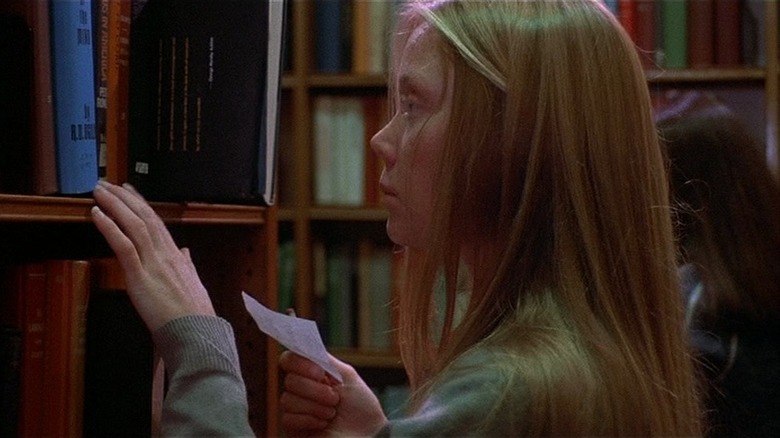

Carrie's mother makes her home life utterly miserable, and school provides absolutely no relief: If anything, it's even more humiliating. Carrie desperately wants to fit in, but all her efforts come to nothing. Even when she manages to scrimp and save enough to pay her own way to Christian Youth Camp — away from her mother's stern restrictions — she faces constant mockery and "a thousand practical jokes," and she eventually has to come home early just to escape.

High school, of course, only makes things worse. The novel recounts a wide range of torments, from Carrie being pinched and tripped to having peanut butter put in her hair. Most of all, everything bad and awkward that happens to Carrie — typical adolescent acne, getting a bad case of poison ivy, or splitting her skirt — becomes fodder for endless public ragging. Her self-esteem is ripped to shreds on a daily basis.

The regular bullying reaches its peak on the day of Carrie's first period, but even before that, her peers make sure that she's unhappy and deeply lonely.

The trauma of Carrie's first period set a tragedy in motion

Carrie gets her period unusually late, once she's already in high school, and she's completely unprepared for it. Her mother never told her anything about menstruation, so when she sees that she's bleeding — without, so far as she can tell, any cause — she understandably panics. She genuinely thinks she might be dying.

This would be an awful, traumatic experience under the best of circumstances, — but Carrie is so unlucky that it happens at the worst possible time: while she's showering in a crowded school locker room. The 1976 film offers a particularly visceral, horrifying vision of a naked, terrified Carrie confronted with the other girls' disgust and ridicule as they pelt her with tampons and pads, chanting, "Plug it up! Plug it up!" as she cowers in fear. The girls in the 2013 remake movie make a little more effort to be nice at first, but once the situation devolves, the movie adds a particularly awful contemporary twist: Chris Hargensen records the whole humiliating experience on her phone, all the better to make sure Carrie can never, ever live it down. That video comes back on prom night, sealing the deal on Carrie's climactic rage.

A horrific prom night prank made Carrie snap

Sue Snell feels real guilt about joining in with everyone bullying Carrie, so she makes the bold — and ultimately ill-fated — choice of asking her boyfriend, Tommy Ross, to take Carrie to the prom, just so Carrie can have one nice, ordinary high school milestone.

Unfortunately, Sue doesn't count on Chris Hargensen's vindictiveness. Chris is the most vicious of Carrie's bullies, and she refuses to accept the grueling detention their gym teacher insists on as punishment for the locker room incident. When that gets her banned from prom, Chris — with the aid of her sociopathic boyfriend Billy — decides to strike back at Carrie: She arranges for Carrie to be elected prom queen, and then dumps a bucket full of pig's blood on her head, drenching her in front of the crowd.

It's a horrible, iconic moment, and the 2013 film even exacerbates it by having the video of Carrie's locker room breakdown projected for everyone to see. Faced with all this humiliation, horror, paranoia, heartbreak, and the conviction that her one moment of happiness was a joke all along, Carrie shatters.

Carrie turned prom into an apocalypse

When Carrie's fairy tale of a prom night ends with her covered head-to-toe in blood, all her tentative happiness comes crashing down around her. In the novel, she temporarily retreats, even running out onto the lawn, and it's only when she thinks about the further shame and defeat that would come from crawling back to her mother that she decides to take revenge. The movie adaptations usually compress the timeline and keep her in the gym, although the 2013 film gives her time to react to Tommy's accidental death — the final touch that pushes her over the edge.

Carrie's telekinetic evisceration of her prom is presented differently in each version, but in all of them, she does her best to trap everyone in the gym — sometimes gorily killing or injuring them when they try to escape — while she burns the place down in an electrical fire. By this point, she sees everyone around her as a source of vicious, unending torment, and consciously or unconsciously, she pays them back with the same kind of hellfire her mother always told her about. The fire is a physical manifestation of her now-unchecked fury.

Carrie destroyed most of her home town

Carrie's wave of enraged destruction continues even after she leaves the school. In the 1976 and 2013 films, she limits this to just taking out her remaining tormentors: Chris Hargensen, Billy Nolan, and her mother.

She's less focused in the novel and the 2002 adaptation, however — she brings a good chunk of the town down with her, leaving fire and rubble behind her as she heads for home. The book provides the most vivid account of the devastation, including excerpted testimony from multiple characters reporting on the damage. Carrie makes gas mains explode and leak everywhere, starting numerous fires when someone unknowingly throws out a lit cigarette, and she also duplicates the electrical fire she caused in the gym by opening up fire hydrants and then snapping the power lines to produce a flood of sparks.

Sources in the novel attribute at least 440 deaths to Carrie's rampage — a tragedy so extensive and (especially considering the youth of many of the victims) overwhelming that it effectively puts an end to the entire town. Even the survivors feel hollowed out by all the destruction.

Carrie murdered her mother

After a catastrophic prom night, Carrie comes home only to face the final and most devastating rejection of her life. Her own mother not only tries to kill her — attacking her with a knife or, in the 2002 TV film, trying to drown her in the bathtub — she also admits to having almost killed Carrie several times before.

In the novel, Carrie is willing to forgive her mother's murderous plans in exchange for whatever paltry comfort her mother can offer her, but Margaret isn't willing to move on. She plunges a knife into Carrie, and Carrie — in a scene that's dark but undoubtedly satisfying — makes her pay for it. In the book and 2002 adaptation, Carrie uses her powers to stop her mother's heart; in the 1976 and 2013 films, she uses knives, scissors, and other sharp objects to impale her in a crucifixion-style pose, giving Margaret a grislier death, but one with symbolism she might have appreciated ... at least under other circumstances.

After seeing how badly Margaret White warped her daughter, it's hard for us to mourn her death — but this isn't a triumphant, vindictive moment for Carrie. It's a devastating one. No matter how much she may hate her mother, she loves her, too, and once she's gone, Carrie has almost nothing left.

Carrie spent her last moments telepathically linked to Sue Snell

While most of the adaptations minimize Carrie's telepathy or leave it out completely, the novel makes significant use of it in the final section. Carrie is able to mentally broadcast her rage and sense of grievance to the whole town, making sure that, after a lifetime of being either ignored or derided, she finally takes center stage in a way of her choosing.

Her telepathic connection to Sue Snell, however, is much more intimate. Sue finds a severely injured Carrie, and the two of them link minds. At first, Carrie inundates Sue with all the excruciating memories of her trauma, accusing Sue of tricking her like all the rest, but Sue proves her relative innocence by letting Carrie pry into her own memories and complicated, messy feelings. Because she can tell that Sue didn't mean for this to happen to her, the exhausted, defeated Carrie spares her life — but to Sue's discomfort and horror, they stay mentally connected as Carrie dies, and Sue is forced to perceive that moment of death as if it were her own.

Even when adaptations don't go this route, they still usually imply a profound connection between Carrie and Sue — in the 2002 film, Sue even saves Carrie's life — that's emotionally intense, even if it's also traumatizing enough to lead to one of horror's most famous jump scares.

In The Rage: Carrie 2, Carrie's half-sister causes another tragedy

Aside from a stage musical that was a notorious flop, the "Carrie" franchise has stayed fairly contained, without the usual follow-ups and spin-offs. You've got one book, a couple movie adaptations, and that's it. The one exception is the surprisingly entertaining 1999 sequel "The Rage: Carrie 2."

Despite flatlining at the box office, "The Rage" deserves to be in any round-up of Carrie White's pop culture history. The movie gives Carrie an unknown half-sister, Rachel Lang, whose family history is eventually uncovered by an adult Sue Snell, now a high school guidance counselor. Though Rachel is stigmatized by her peers, she has a little more self-esteem than Carrie. She even has a friend, Lisa ... until a misogynist sexual game played by the school's jocks drives Lisa to suicide. While fighting for justice for Lisa, Rachel unexpectedly falls in love with the popular Jesse — but then a cruel prank convinces her that their relationship was a trick all along.

Losing the person she cares about most again drives Rachel over the edge, and she uses her telekinetic powers to completely eviscerate her classmates in a climactic party scene. (Rachel is even more inventive in her executions than Carrie, with her murder spree utilizing everything from a harpoon to a pair of glasses.) As a final twist of the knife, Rachel's eventual telekinetic rampage ends Sue Snell's hope of preventing the tragedy this time around — and ends Sue's life in the bargain.