The 6 Best And 6 Worst Things In The Whale

Contains spoilers for "The Whale."

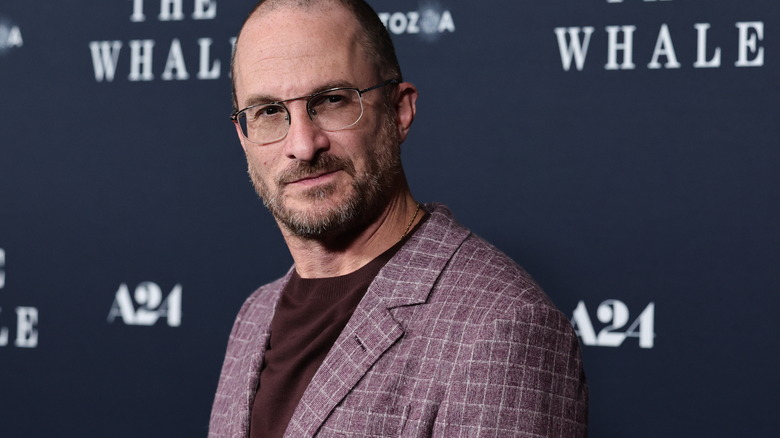

Adapted from a Samuel D. Hunter play of the same name (with Hunter also penning the screenplay adaptation), "The Whale" is a Darren Aronofsky directorial effort chronicling a week in the life of Charlie (Brendan Fraser). This man, after suffering several harrowing personal tragedies, has become a recluse who now weighs 600 pounds and grapples with a wide assortment of health problems, though he refuses any sort of medical treatment. The film begins as Charlie grows more and more cognizant that his end is drawing near and he wants to reconnect with the daughter, Ellie (Sadie Sink), whom he became estranged from years earlier. It's a harrowing story, but also one filled with emotionally tender moments that allow great actors like Fraser and Hong Chau plenty of room to excel.

"The Whale" is a movie that's bound to inspire plenty of conversation, and for good reason. This is a complicated feature, one that has a lot of love for its lead character but can also indulge in some stereotypes about fat people. That's just one of the ways this film can sometimes stumble even when it's soaring in other areas. Breaking down the best and worst aspects of this feature makes one realize "The Whale" is far from flawless, but also appreciate the bold swings it takes.

Worst: The score by Rob Simonsen

In what's easily his most prolific solo credit as a composer to date, Rob Simonsen provides compositions that underline the emotions of Charlie's tormented existence. Throughout the runtime of "The Whale," Simonsen does deliver some solid pieces of music that nicely compliment, rather than overwhelm, the performances on-screen. Unfortunately, his compositions have a bad habit of being overly intrusive. Moments that need to just let dialogue simmer on-screen free of musical accompaniment are instead blaringly undercut by Simonsen's score.

This becomes especially apparent as the home stretch of "The Whale" gets underway. As the mood of the entire movie gets darker, Charlie and the other characters become more vulnerable, but unfortunately, Simonsen's score also grows increasingly abrasive. The issues with his compositions only worsen as "The Whale" continues. It's disappointing that the instrumentation in his score isn't very creative. Charlie, as presented in this script, is a one-of-a-kind person and his story deserves to be told with music punctuated by equally idiosyncratic instruments. Simonsen's score is a letdown in this department and tends to undercut the most important emotional beats of "The Whale."

Best: Hong Chau's performance

It's a welcome development to see 2022 as the year where Hong Chau is suddenly showing up everywhere. Given her talented performances in films like "Driveways" and "Inherent Vice," she's always an incredibly welcome presence in any feature. With her work as a nurse and good friend Liz in "The Whale," Chau adds another impressive performance to her resume. She shares most of her screen time with Brendan Fraser's Charlie, and while his towering performance would ordinarily overwhelm any other actors in the vicinity, instead, Chau excels working off him.

Among her many great feats in this role, Chau is especially good at showing Liz shifting her attitude on a dime. She can go from being nonchalant and chatty to severe and determined without even blinking, a fantastic representation of how Charlie's health problems can come from out of nowhere and upend her existence. Her big solo scene with Thomas (Ty Simpkins), in which she comes clean about her backstory and her connection to Charlie, is an especially masterful showcase of Chau's acting gifts. She starts slow in this sequence as if it's hard to pry the words from her lips, before gradually building up to a mighty fury that spills out of her mouth. The organic nature of every line delivery in this scene encapsulates just how outstanding Hong Chau is in "The Whale."

Worst: Some of the fat jokes

Screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter lends a generally empathetic lens to the story of Charlie in "The Whale," but to reflect the darker aspects of humanity, the script does indulge in an old favorite of movies in any genre: fat jokes. It's not a surprising element in the film nor is it necessarily something totally uncalled for. The character of Ellie, specifically, is a figure who acts edgy and rebellious toward everyone. It only makes sense that she would make various fat jokes about her father, intentionally trying to wound him. The problem is that some of the jokes Hunter comes up with are pretty tired. If we're going down this road, must we also travel to such familiar comedic territory?

A perfect example of this is a comment made by Ellie after Thomas expresses shock that this teenager is Charlie's daughter. This inspires Ellie to comment "What's more surprising, that a gay man could have kids or that somebody found his penis?" The punchline of this joke was overdone when a "Family Guy" episode trotted it out as a running gag nearly 20 years ago, let alone when it appeared in a Darren Aronofsky drama in 2022. Fat jokes aren't necessarily out of place in this story, but they should've been executed with way more creativity at least.

Best: Darren Aronofsky expanding his tonal palette

Since he started directing movies in 1998 with "Pi," Darren Aronofsky has been well-known as a filmmaker who tends to keep himself at a distance from his characters and lather his stories in rampant darkness. These approaches have had varying degrees of success: His decision, for example, to twist the story of "Noah" into something akin to "The Shining" works perfectly. Meanwhile, other productions like "Requiem for a Dream" have suffered because of a lack of human touch or empathy for the characters on-screen. A filmmaker who has been known for his cold approach (sometimes to masterful effect) goes for a much different tone in "The Whale," a movie that's all about grand emotional gestures and a protagonist espousing an optimistic view of the world.

Traces of Aronofsky's default style creep into "The Whale," most notably in the bleak depiction of the world outside of Charlie's apartment or a third act scene depicting him engaging in binge eating. For the most part, though, "The Whale" is a much more intimate and grounded project, while its tone allows for more comedic moments than all of Aronofsky's prior movies combined. The director's inexperience with pronounced displays of sentimentality is sometimes awkwardly apparent, but for the most part, Aronofsky taking a tonal detour in his filmography for "The Whale" proves to be a creatively fulfilling exercise.

Worst: The missed opportunities in the aspect ratio

"The Whale" is told largely through a more narrow 1.33: 1 aspect ratio, a format commonly associated with vintage 20th century movies made in the Academy Ratio. In recent years, this format has become a staple of arthouse cinema, with it and similarly cramped aspect ratios appearing in movies ranging from "The Grand Budapest Hotel" to "First Cow" to "The Lighthouse." What was a tremendously unique visual detail in 2014 is now commonplace in the modern arthouse movie scene, though its ubiquity at least means many films have used it to great effect. "The Whale" doesn't necessarily use this format poorly, but it isn't an especially inspired use of the Academy Ratio.

Many films that utilize this aspect ratio tend to provide very precise blocking and framing that take advantage of the minimal amount of space in any given frame. "The Whale," on the other hand, mostly just captures the conversations and physical behavior of its characters in the same manner that it would if it were filmed in a more traditional aspect ratio. While the cramped spacing seems conceptually like a clever visual extension of Charlie's closed-off life, in execution, "The Whale" could've done way more with telling its story in a 1.33: 1 format.

Best: The subtle commentary on humanity

While the protagonist of "The Whale" carries a constantly optimistic view of the world around him, the movie itself is much more conscious about the shortcomings of humanity. It never travels beyond Charlie's apartment (save for two brief flashbacks to a sunny day at the beach from years earlier), but the glimpses we see of the outside world from his window reflect a landscape covered in fog and rain. The further views we get of the broader world are through spurts of commentary on the GOP primaries on Charlie's TV, with the presence of political figures like Ted Cruz and Donald Trump suggesting the rot in national and global leadership.

Offhand comments from other characters, all of whom now reside in Idaho, also reflect the economic despair these individuals are struggling to survive. Liz remarks in the third act that her car broke down the previous winter and she had to trudge through the snow to get Charlie's groceries. Through Facebook posts, we see that Ellie and Mary (Samantha Morton) are now living in a small shack near a Walmart, reflecting their poverty. While people like Cruz and Trump get richer and more powerful, working-class individuals struggle to make rent. Add in the presence of a hypocritical Christian organization that talks about "God's love" while spewing homophobic rhetoric and "The Whale," through its reflection of the darker parts of humanity, subtly makes Charlie's optimistic outlook all the more impressive.

Worst: Certain visual shorthands for Charlie's eating habits

The way "The Whale" approaches fatness in its lead character Charlie is ... complicated. It's a treatment that's bound to inspire conversation and much of it will be very understandable. For the most part, the decision to tell the story of "The Whale" through his eyes and emphasize his complexity as a human being (including how he has things like a sex drive and a job even while cutting himself off physically from the world) makes the film far less cringe-inducing than you might expect. In a handful of other respects, though, it is frustrating that "The Whale" indulges in some derivative visual shorthands to indicate to the audience that they're watching a story set in a fat person's house.

Specifically, the constant presence of a half-guzzled Diet Pepsi in Charlie's living room is a visual detail that plays on an ironic concept (the notion of fat people being obsessed with diet sodas) that's been done to death in other pop culture properties. Similarly, the messy nature of Charlie's living room or a drawer full of candy feel too familiar and evocative of other movies and TV shows chronicling the living spaces of fat people. It's not like those elements can never exist in a fat person's domicile, but "The Whale" indulging in these tired pieces of visual shorthand betrays its more empathetic quality as a movie.

Best: The emphasis on Charlie having a sex drive

The classical depiction of fat people in mainstream cinema has reinforced the idea that the mere thought of them pursuing sex is largely something to be mocked. This mockery manifests in different ways, but they typically carry the undercurrent that the concept of fat people wanting sex or being sexually attractive is ludicrous. "The Whale" opts to push back against that perception right away by making sure that the first time the viewer sees Charlie is when he's pleasuring himself to graphic videos of men engaging in physical intimacy. The image itself isn't supposed to be funny, but rather an indication of the kind of vulnerability Charlie will be exhibiting throughout the subsequent movie.

Later on, the viewer sees various framed photos lingering around Charlie's apartment showing him and his now-deceased partner smiling together on beaches or next to mountains. Upon being reminded of this past, Charlie notes that he was always a bigger man in size, but that he was always loved by his husband. This nonchalant depiction of romantic satisfaction for somebody that doesn't conform to the rampant skinniness in Hollywood productions is an incredibly welcome sight to see. "The Whale" sometimes succumbs to harmful media clichés about fat people, but its willingness to depict Charlie as a sexually vibrant human being is a welcome departure from those norms.

Worst: The brief tension between Liz and Charlie

In the third act of "The Whale," a source of enormous friction comes between Charlie and Liz once the latter character finds out that Charlie secretly has around $120,000 in his bank account, all of which he's kept for Ellie. Understandably, Liz is aghast at this revelation, since it means that Charlie always had the money necessary for health care or to pay for transportation when her car broke down the previous winter. After this reveal, Liz storms out of Charlie's apartment, with her abrupt exit indicating that one of the few friendships Charlie had has come to an end. However, shortly afterward, Liz returns to Charlie's side to care for him in his final hours. There's clearly some tension between the two in their conversations, but she's returned to her caretaking role again.

Liz's response to Charlie's secrecy is incredibly understandable, and the same is true for why she'd come back to help the dying Charlie. However, in the context of the story, this sudden deterioration of a previously flourishing friendship feels superfluous. Liz's betrayal by Charlie comes in the middle of a scene where there's already so much tension from Charlie interacting with his ex-wife, Mary (Samantha Morton). It doesn't feel like we need further animosity in this sequence while the lack of resolution for Liz's feelings is incredibly frustrating. The idea behind this plot point involving Liz and Charlie isn't bad, but the execution could have used work.

Best: The makeup and prosthetics

To play the character of Charlie, Brendan Fraser needed to embrace the glories of makeup and prosthetics. Fraser wore varying heavy layers of prosthetics on set (while also making use of CGI touch-ups added in post-production) that completely transformed him into another human being who could believably look like they weighed 600 pounds. Having Fraser in prosthetics play this role rather than an actual fat person will inspire some understandable controversy, but in the context of "The Whale" from a technical perspective, the makeup work on display is quite impressive. The film's makeup department delivers remarkable results, making sure that Fraser looks like a wholly new person rather than a constant reminder of his classic comedy roles from the 1990s.

What's especially impressive about the makeup work in "The Whale" is how it stands up under the feature's extremely subdued tone and aesthetic. This is a movie that's all about lengthy quiet conversations, with the camera glued to Fraser's face and other parts of his body covered in makeup and prosthetics. If these elements looked distractingly fake, the intimate tone of these exchanges would be crushed. Thankfully, the makeup work here is so strong that it registers as convincing no matter how long it stays on-screen, thus ensuring that the most pivotal emotional scenes aren't disrupted.

Worst: The ending

"The Whale" comes to a close with a scene that pulls out all the stops in trying to evoke emotions in the viewer. Charlie, in his dying moments on his couch, tells Ellie how amazing she is before begging her to read aloud an essay she wrote about "Moby Dick" in eighth grade. As Ellie proceeds to read the paper aloud, Charlie moves off the couch and begins to take a series of steps toward her daughter. As he finally reaches his child, Ellie finishes the essay, Charlie looks to the sky, and the audience sees his feet begin to ascend into the air as overwhelming light consumes the screen. The last image the viewer sees is a wide shot of Charlie, Ellie, and Mary at the beach years earlier.

The big problem with this ending is that it's way too overwhelming rather than emotionally sweeping. Between the intrusive score, the quick cuts between Charlie and Ellie, and the obvious imagery suggesting Charlie is heading to Heaven, it's a lot of very big elements that drown out the characters and their perspectives. This conclusion feels like it would've worked better on stage, where the innate sparseness of live theater could've shifted the focus onto Charlie and Ellie. In its film form, though, the ending of "The Whale" is undercut by images and sounds working far too hard to pluck at the heartstrings.

Best: Brendan Fraser's performance

Given all the hype surrounding Brendan Fraser's work in "The Whale," it's easy to imagine that, in the future, the reputation of this film as Fraser's big comeback vehicle will surpass any concrete details of the performance itself. Given that, it's important to remember that his work in "The Whale" is still incredibly strong. While on paper, casting Fraser as Charlie sounds like trite stunt-casting, this talented actor turns out to be a perfect fit for the role. Fraser can juggle the tormented and optimistic sides of Charlie's psyche with ease and subtlety, he's able to make such fragmented psychology incredibly organic. Fraser's vast experience with comedy also helps him nail some of Charlie's lighter line deliveries, such as his memorable delivery of the phrase "that's an interesting perspective" in response to Ellie's dismissive attitude towards the works of Walt Whitman.

Best of all, though, is the warmth and humanity Fraser exudes in the role, which goes a long way in ensuring that "The Whale" isn't just wall-to-wall fatphobia. Fraser manifests Charlie as a human being, a figure audiences should empathize with rather than mock. Conveying those qualities in such believable and compelling terms ensures that "The Whale" does live up to the hype when it comes to providing Brendan Fraser with an incredible dramatic star vehicle.