15 Great Modern Movies Filmed In Black And White

When the sepia tones of "The Wizard of Oz" seamlessly transformed into a technicolor world in 1939, it was like a revelation. As The National Museum of American History points out, Victor Fleming's classic wasn't the first movie to use color. Still, it was the first film to open up the true potential of its groundbreaking palette, with the already fantastical film made even more remarkable by the alluring shade of Dorothy's ruby red slippers, the irresistible hue of the wayfinding yellow brick road, and the toxic green of the Wicked Witch's face. When Dorothy opened the door of her little Kansas farmhouse and walked away from a monochrome world into one of glorious color, imagination, and possibility, the audience walked into it with her. Who would predict then that one distant day in the future, filmmakers would lament the days of black and white and revert to making films in that format — not out of necessity but choice?

Esquire reports that George Miller wanted "Mad Max: Fury Road" to be released in black and white, but the studio strongly disagreed for commercial reasons. To this day, the director insists that "The best version of this movie is black and white, but people reserve that for art movies now." Miller is far from alone in his passion for the old-school way of shooting movies, and everyone from Martin Scorsese to Steven Spielberg has created critically acclaimed films in black and white. Here are 15 of the best modern movies shot in black and white.

Belfast

Kenneth Branagh's "Belfast" is a riveting account of a childhood spent in Northern Ireland in the late '60s, during the onset of the troubles. Although loosely based on Branagh's own experiences, "Belfast" is more a biopic of a time and place than an individual. The black and white footage adds a historic and timeless element, taking the personal experiences and making them universal. In an interview with Vanity Fair, Branagh explained how the Covid-19 pandemic helped make the film a reality. He remarked how lockdown "reminded me of a fragility in our lives" and he "felt obliged and compelled" to make a movie that captured the world of his childhood — a world that would be rendered colorless.

Splashes of color are used extremely sparingly in "Belfast," and it is revealing that it features in the scene when Buddy (Jude Hill) and his family pay a trip to the movie house. The contrast between the sharp and uncompromising world of black and white, with the glorious and indulgent kingdom of color, is a stand-out moment and a tribute to the transformative nature of films. Branagh told Vanity Fair, "The cinema, for me, was one place where the screen engulfed you so totally that you could, for those moments, forget." "Belfast" cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos told The Wrap that Branagh, "Really loves the transcendental quality of black and white. It can be the present and the past at the same time."

La Haine

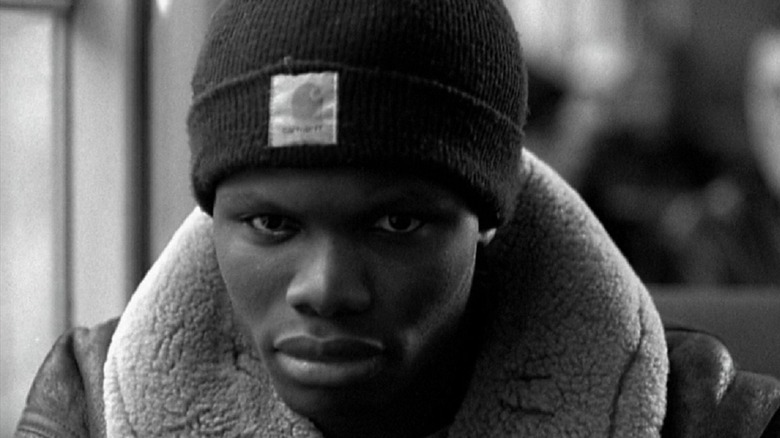

Director Mathieu Kassovitz's masterpiece about three young friends from Paris — and the effect one day and night has on them all — is an engaging reflection on the divisions that threaten to rip society apart. Condemned to an aimless existence, the three urban musketeers — Vinz (Vincent Cassel), Hubert (Hubert Koundé, and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) — are universal representatives of angry young men everywhere.

Shot in black and white, "La Haine" perfectly captures the feelings of rage, hopelessness, and frustration that often define a generation of young people condemned to the margins and denied a foothold in the world. In a bid for authenticity, all three leading actors used their real first names in "La Haine" (per Esquire). This is a decision that pays off — as does the choice to film in black and white due to financial reasons.

Although it may not have been a strictly aesthetic decision to make the movie in black and white, it adds to the dynamic of the film. Devoid of color, the Paris in "La Haine" is transformed from the city of a million romantic getaways into an indifferent urban rat trap. Such was the divisive nature of the film, that when Kassovitz won the best director award at Cannes for "La Haine," the police guards at the ceremony "turned their backs on him in protest" (via The Guardian). By telling its tale in black and white, "La Haine" has a documentary feel — it is social realism, not escapism, and it packs a knockout punch.

Schindler's List

When the world woke up to the terrible reality of the Holocaust in the wake of World War II, it turned history on its head. When harrowing black and white photographs and grainy footage emerged from the concentration camps, it served as a terrible testament to the atrocities committed and the disregard for human life. The uniquely desolate nature of the Holocaust is encapsulated perfectly by Steven Spielberg's decision to shoot "Schindler's List" in black and white. The film is drained of color, reflecting the way the Holocaust stole so much life and energy from the world. For the brief moments when color is introduced — such as the scene featuring the girl in a red dress — it has a life-affirming poignancy.

As well as the decision to shoot in black and white, Spielberg also chose not to include subtitles in "Schindler's List." In an interview with Inside Film, Spielberg explained he deliberately did this because he, "wanted people to watch the images, not read the subtitles. There's too much safety in reading. It would have been an excuse to take their eyes off the screen and watch something else." By doing this — and opting to not film in color — Spielberg allows the images to speak for themselves, creating a movie where shadows and light sharply define the duality of good and evil and capture the historic nature of the Holocaust without diminishing it.

Raging Bull

From the iconic opening scene — featuring Jake LaMotta (Rober De Niro) boxing his own shadow — Martin Scorsese's "Raging Bull" has a classic, timeless feel that would seem tainted by something as garish as color. Scorsese once lamented to MasterClass about the death of black and white and how he missed it. He elaborated, "I was fascinated by three-strip technicolor. Yet black and white existed alongside it and had its own sense of color ... It had its own style. It had its own meaning." Yet Scorsese's decision to shoot "Raging Bull" in black and white was more of a happy accident than a deliberate ploy.

When shooting De Niro fighting in the ring in 8mm color, the color of his gloves wasn't reflective of the deep oxblood red more associated with the '40s. By switching to film in black and white they neatly sidestepped such inconveniences and simultaneously captured the newsreel look of the period. Additionally, Scorsese was also developing something of an obsession with film preservation, and realizing black and white footage would outlive color stock he saw a chance to immortalize "Raging Bull" (via Cinephilia And Beyond).

It has also been suggested that Scorsese was keen to make the movie in black and white to avoid any comparisons with "Rocky" (per The Sportsman.) Whatever the reason, the black and white footage puts "Raging Bull" in a class of its own, and the absence of colorful visuals allows the character of LaMotta to shine through in all its stark and epic tragedy.

Roma

In their review of "Roma," The National News enthused that "every single shot" of Alfonso Cuarón's film "deserves to hang in The Louvre." It may sound like hyperbole, but anyone familiar with the drama — focusing on the plight of an indigenous maid (Yalitza Aparicio) working in a middle-class white household in '70s' Mexico City — will appreciate just how masterfully this moving tale is framed. The visuals wash over the viewer and tell their own story, and being shot in black and white is a big part of their power.

In an interview with IndieWire, Cuarón revealed that he chose black and white because, "I didn't want a film that looks vintage, that looks old. I wanted to do a modern film that looks into the past ... It's not a vintage black and white. It's a contemporary black and white." Cuarón — who based the film loosely on his own experiences growing up in Mexico City — added that because the film was about the character Cleo and "the tune was memory" he believed he could only capture the essence of the past by using black and white footage. The lack of color in "Roma" serves to emphasize the drudgery and dreariness that threatens to overwhelm Cleo — yet it also highlights her spirit and strength of character and allows it to shine like an inner light throughout the film.

The Elephant Man

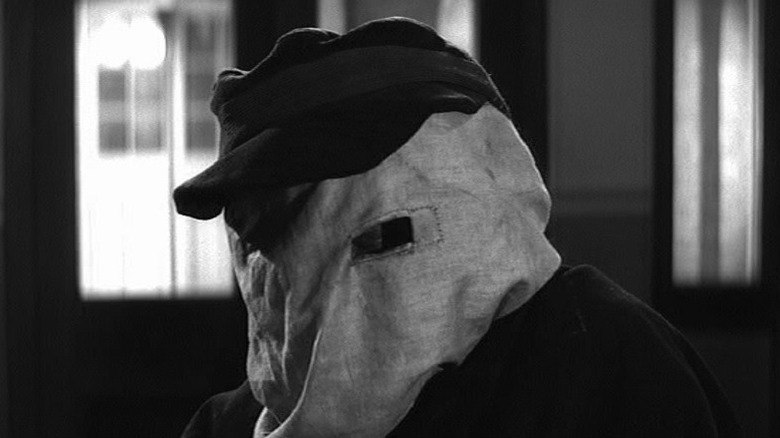

To recreate the unique and striking facial features of the real-life Joseph Merrick (named John Merrick in the film) for David Lynch's "The Elephant Man" was no small task. Prosthetic make-up artist Christopher Tucker was tasked with capturing the humanity behind the disfigurement and deformity that saw Merrick cruelly branded a freak by his contemporaries (via Dangerous Minds). By sitting in the make-up chair for seven to eight hours, John Hurt was able to physically transform into Merrick in a haunting portrayal that once seen is never forgotten. By filming "The Elephant Man" in black and white, Merrick's appearance is softened somewhat and doesn't distract the viewer from the human beneath. It refuses to play for shocks and captures the often grim and claustrophobic feel of the Victorian era.

Courtesy of the grainy and atmospheric footage of cinematographer Freddie Francis, Lynch presents a world devoid of color which adds to the surreal and dream-like nature of "The Elephant Man." Despite dealing with a very real individual, the film exists in a fantastical universe, where strangeness exists in the shadows on the edge of consciousness. Speaking about the film's visual style, Lynch explained, "I always thought of 'The Elephant Man' as a black and white film. Black and white immediately takes you out of the real world" (via Time). Following his debut feature film "Eraserhead," "The Elephant Man" marked Lynch's second black and white movie, and it was only with the release of "Dune" four years later that the world finally got a taste of a color movie from the director.

Muscle

Craig Fairbass is a criminally underrated actor — perhaps because he's often cast as the shouty cockney criminal, who is physically intimidating but requires little in the way of acting chops. Yet when he's given the sort of script and character that allows him to flourish, he's a class act. In director Gerad Johnson's "Muscle," Fairbass pulls out all the stops as a personal trainer, Terry, who is consumed by machismo and spends his days in a murky subculture of dumbbells and sleaze. When office worker Simon (Cavan Clerkin) enlists Terry's expertise to train him, Terry is only too happy to help. Yet all that toxic masculinity and chest-beating bravado come at a cost, and "Muscle" is a study of the price men pay.

"Muscle" is a bleak and cautionary tale set in a grim and desolate environment. Its message that physical self-improvement can also lead to mental self-destruction leads to many bleakly comic episodes. In a world without nuance — where strength is celebrated and weakness is scorned — "Muscle" is a hard watch, and shooting it in black and white reflects the lack of grey area. In an interview with Cineuropa, Johnson explained that opting to film in black and white helped soften the impact of the notorious orgy scene and that he was "drawn to the British New Wave from the 1960s" for inspiration. Influenced by films including "Taste of Honey" and "Saturday Night and Sunday Morning," Johnson said of "Muscle," "It was always black and white in my head."

Dead Man

When you're watching a Western about a mild-mannered accountant named William Blake (Johnny Depp) — who slowly transforms into a murderous outlaw and hangs out with a Native American spirit guide called Nobody (Gary Farmer) — you know you've strayed a long way from John Wayne territory. Yet as weirdly captivating as director Jim Jarmusch's acid-Western is, the decision to make it in black and white makes the strange a whole lot stranger. The unsettling oddness of a town called Machine and its peculiar inhabitants is exaggerated by the monochrome photography — the Wild West has never looked any wilder than it does in Jarmusch's film.

In an interview with The Harvard Crimson, Jarmusch revealed his ambition with "Dead Man" was to push the boundaries of the Western genre in every feasible form. Blake is a cut apart from the dynamic go-getting heroes most often found in the genre, and that's because Jarmusch opted to render him a passive victim of circumstance as opposed to an architect of his own destiny. However, it's the black and white footage that gives "Dead Man" its otherworldly vibe and places it in stark contrast to the vivid hues often associated with Westerns. Jarmusch admits that shooting in color was never an option and stressed he had always visualized the film in black and white. The director explained, "A guy goes into a world that becomes very unfamiliar to him and the black and white allowed that kind of eerie, unfamiliar quality to be maintained."

Twenty Four Seven

Shane Meadows' "Twenty Four Seven" is a sporting drama with a difference. In place of a heartwarming story about an individual or team defeating the odds, there exists a simple tale of the world-weary former boxer, Alan Darcy (Bob Hoskins), who strives to help get kids off the streets and into the ring to build self-esteem, confidence, and a positive mindset. "Twenty-Four Seven" is all about channeling the aggression of disaffected young people growing up in a deprived and claustrophobic environment, and its black and white footage perfectly encapsulates the ennui of many working-class areas in '90s Britain. It's a world without color, where a lack of purpose and drive has left a generation struggling to get out of bed and fight for opportunities in life.

Hoskins' character opens a gym and teaches the lads how to stand their ground and win respect in a world that doesn't want them to succeed. It's gritty and hard-hitting stuff, and Meadows pulls no punches on his feature film debut. In a 1998 interview, Meadows credits the success of his short film, "Where's The Money, Ronnie?" as the reason the producers of "Twenty Four Seven" trusted him enough to make a successful feature-length movie in black and white. "Twenty-Four Seven" ends in tragedy but before it does, it sows the seeds of hope with the message that when the world defines you as a nobody, it's up to you to be a somebody.

The Last Picture Show

"The Last Picture Show" is all about nostalgia and the passing of time in a small town in the '50s. Such themes are tailormade for black and white, and director Peter Bogdanovich does a fine job of evocatively capturing a decade that has been mythologized endlessly. The town of Anarene is universally recognizable as one whose glory days are already long gone, and the lack of any future is disguised by reminiscing about the good old days. The characters — Sonny (Timothy Bottoms), Jacy (Cybill Shepherd), Duane (Jeff Bridges), and Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson) — have an everyman quality that makes them extremely relatable. However, their portrayal in black and white puts a barrier between them and the audience which suggests they are like you but not you — archetypes trapped in a world of their own making.

The black-and-white nature of "The Last Picture Show" is a reminder that the promise of endless youth and capitalism without consequences is a lie. As the name of the film suggests, "The Last Picture Show" is one that will be shot without color because the sun has finally set on a long-held dream. A melancholy mood pervades every scene, and it seems to suggest that Anarene is a town full of ghosts, inhabiting a world that should no longer exist. Director of photography Robert Surtees explained to American Cinematographer, "I hate to see black and white go completely because it's absolutely right for certain types of stories" — and "The Last Picture Show" is definitely one of those stories.

Ed Wood

Tim Burton's heartfelt tribute to a true maverick movie maker may be shot in black and white, but it's a colorful depiction of a colorful character whose passion was unfortunately not matched by his talent. While Ed Wood was often hailed as "the worst filmmaker of all time" (via Cinephilia and Beyond), anyone who's experienced the giddy B-movie joy of "Plan 9 from Outer Space" knows this is an unfair label to pin on him. It is particularly unfair considering he is an individual whose sheer strangeness makes him the perfect lead character for a film about an outcast, who cares not one iota about fitting in.

Because it is shot in black and white, "Ed Wood" highlights the outsider status of its chief protagonist — played with exceptional reverence by frequent Burton collaborator, Johnny Depp. He's a man on the outside looking in and operates in the realm of another universe. And although there may be no color in that distant realm, there are stars and they burn bright and fierce. In his review of "Ed Wood," Roger Ebert hailed the film's visual style and wrote, "It convincingly recaptures the look and feel of 1950s sleaze, including some of the least convincing special effects in movie history."

Control

Anyone familiar with Joy Division's music will appreciate its stark, urban beauty. There's nothing pastoral or soothing about it — it is the post-industrial sound of a ravaged and bleak landscape. It's angular, sparse, and cuts to the bone. It's powerful stuff, and making a film about the band's doomed singer would never have looked right in color. Joy Divison was a product of their environment, and the film accurately reflects the grimness of Manchester in the late '70s and early '80s. Anton Corbijn's "Control" perfectly captures the world Joy Division's frontman Ian Curtis (played by Sam Riley) grew up in and was influenced by.

The black and white cinematography of "Control" is as evocative and atmospheric as Joy Division's music. It adds an artistic dignity to the tragedy of Curtis and gives the domestic mundanity of everyday existence an almost epic quality. In an interview with MovieWeb, Corbijn explained he made "Control" in black and white because of "how I remembered England at the time. Coming from Holland to England, it seemed really bleak and grey." The director also observed that "Every picture you find of them [Joy Division] is going to be in black and white ... So it was not my own preference to be working in the black and white medium. It just felt right for the subject matter."

Clerks

A day in the life of two retail clerks who hate the tedium of working in customer service lends itself naturally to a vision of monochrome life. Director Kevin Smith's cult classic "Clerks" is a darkly comedic study of how Dante Hicks (Brian O'Halloran) and Randal Graves (Jeff Anderson) handle the monotony of dealing with an angry, clueless, and demanding public while getting paid a pittance. Through quasi-philosophical debates on every subject under the sun, the two clerks like to kid themselves that they're somehow superior to their clientele. But as Randal points out, if they were as great as they think they are, they wouldn't be working in the store and complaining.

Although always an engaging and funny watch, you can really feel the drudgery of Dante and Randal's existence, which Smith — who worked as a clerk himself — enhances through the use of black and white. Because it's shot in this way, "Clerks" feels as though Dante and Randal are trapped in a strange retail limbo. They don't know how they ended up there and are not sure if there's a way out — as Dante's repeated lament points out, "I'm not even supposed to be here today." Although many critics felt it was in black and white because it was filmed from the point of view of the store security camera, in an interview on "The Late Show with Stephen Colbert," Smith explained that it was nothing quite as artistic, but simply a case of saving money on his first feature film as a director.

Eraserhead

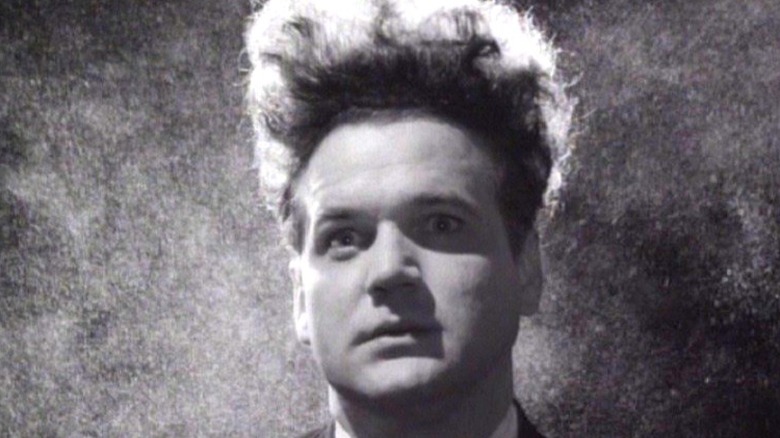

David Lynch's debut "Eraserhead" is a strange and captivating film. It tells the tale of a man (Jack Nance) in a bleak landscape caring for an inhuman, afflicted, and demanding child. With the man also plagued by frightening visions, things would be surreal enough without Lynch opting to film it in black and white. Since its release in 1977, "Eraserhead" has become a cult classic and much of its powerful imagery is familiar to audiences who have not even seen the film. Like all great surrealist works of art, "Eraserhead" bedazzles and beguiles with all the otherworldly, illogical and emotive potency of dreams and nightmares. It is a relentless assault on the senses, and eternally disturbing in its ambiguity.

In an interview with Vulture, Lynch explained that the film "needed to look a certain way, and the look comes about from what's in front of the camera and how it's lit." He went on to profess his adoration for the film saying, "I love the world of Eraserhead. I would love to live in that world. I loved being in there during those years." In the same interview, Lynch said that the interpretations of "Eraserhead" can vary depending on what personal baggage audiences bring to the table, cryptically saying, "No one, to my knowledge, has ever seen the film the way I see it. The interpretation of what it's all about has never been my interpretation."

Sin City

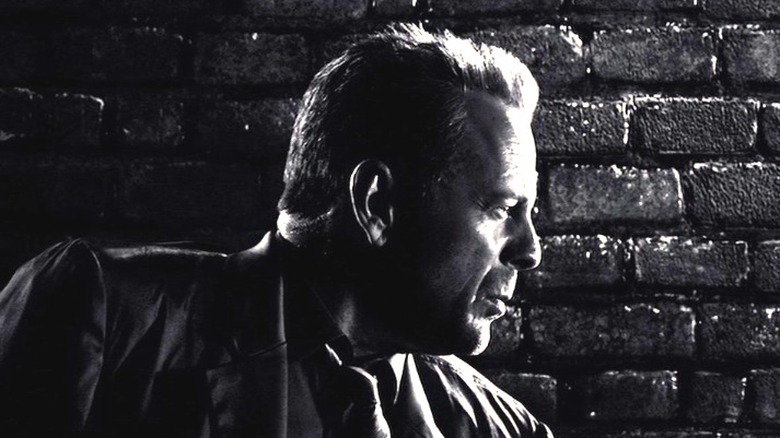

It would have been strange if Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez's "Sin City" had been made in color. The graphic novels it's based upon are celebrated for their atmospheric black-and-white imagery and subtle use of shadows. The comic was heavily influenced by film noir (via Kubert School Media) and so when the movie adaptation came calling, it was always going to take the lead from the graphic novels. With the exception of certain scenes — where color is used to sparingly highlight — the short stories which make up "Sin City" stay true to their monochrome roots.

The stylized and largely colorless nature of "Sin City" evokes the pages of the graphic novel with a punchy dynamic, and makes you feel like you're watching the drawings being brought to life — it's visual candy. In an interview with Wired, "Sin City" co-director Rodriguez explained that he thought the graphic novel's "stories were great, but what grabbed you was the look." Initially shot in color, "Sin City' was turned into the stark black-and-white masterpiece we know and love in post-production. Rodriguez talked about the challenges of shooting "Sin City" saying, "The movie wouldn't even be possible if I shot it on film." Yet film is all about making the impossible possible, and the result of Rodriguez and Miller's work on "Sin City" is striking.