Facts Only True Fans Know About Alan J. Pakula's Paranoia Trilogy

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

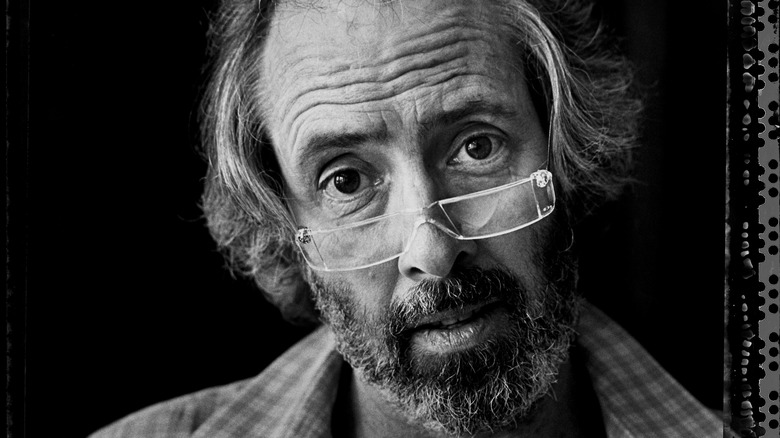

The '70s was an amazing decade for movies, as a new generation of filmmakers took the reigns of Hollywood and churned out classics from "The Godfather," "Chinatown," and "Taxi Driver" to "The Exorcist" "Jaws," "Rocky," and "Star Wars." But although names like Coppola, Lucas, Scorsese and Spielberg are still invoked with reverence today, one that you hear far less frequently is that of Alan J. Pakula — another tremendous filmmaker who stood toe-to-toe with his peers during the decade, making three classics in a row: 1971's "Klute," 1974's "The Parallax View," and 1976' "All the President's Men," the latter still regularly ranked among the greatest films of all time.

Now considered Pakula's "paranoia trilogy," they were thrillers that captured the disillusionment and fear that emerged during the era of Watergate and Vietnam. In "Klute," a hooker could provide the key to solving a murder, and a detective has to protect her from being killed herself. In "The Parallax View," a reporter is trying to get to the bottom of a political assassination, and it leads him into a dense web of conspiracy. In "All the President's Men," Pakula did a masterful adaptation of the best-selling book by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, which detailed how they uncovered the Watergate break in.

All three of these films were strong reflections of their time, and they hold up remarkably well today. In fact, with so many people caught up in conspiracy theories and paranoia in the modern era, these films still have a lot to say. Here are some facts about the Pakula paranoia trilogy that will make you want to dive back into the rabbit hole.

Pakula was an underrated '70s filmmaker

The '70s is considered by some to be the last golden age of cinema, and there were many great filmmakers whose soaring stars propelled the decade. In addition to the aforementioned names, there was George Roy Hill, John Schlesinger, John Carpenter, Brian De Palma, Robert Altman, William Friedkin, Hal Ashby... all cranking out classics.

Yet, for whatever reason, Pakula often goes unmentioned among their ranks. Pakula not only directed the paranoia trilogy films all in a row, he also helmed the wonderfully witty romantic comedy "Starting Over," the acclaimed adaptation of the William Styron novel "Sophie's Choice," and the Harrison Ford thriller "Presumed Innocent," to name a few.

Early in his career, Pakula gave Liza Minelli her breakthrough film role, and helped cast a then-unknown Robert Duvall while producing the big screen adaptation of "To Kill a Mockingbird," nominated for Best Picture and also among the usual suspects for greatest film of all time. As Pakula told Dick Cavett, he knew there was a movie in "Mockingbird," and became determined to get it made.

"On 'Mockingbird,' I happened to call the writer's agent and said I thought there was a film in the book," Pakula told Dick Cavett in 1978. "I walked into her office, and there was Harper Lee, who wrote the book. She took a liking to me; I was rather young and boyish and enthusiastic, intense. I went down South and met her father, the basis for the character Gregory Peck played. She said 'I'd like him to do it,' and so I got the rights to the rights to the book. That was my major contribution, and I worked on the screenplay with Gordon Foote and cast the film."

Killed in a freak car accident on November 19, 1998 at the age of 70, Pakula remains an underrated, underappreciated director long overdue for a rediscovery.

All 3 films were shot by Gordon Willis

Another great talent who helped define the '70s was cinematographer Gordon Willis, who shot all 3 of the paranoia trilogy films, and he also shot the "Godfather" films, "Annie Hall," "Manhattan," "The Paper Chase," and more.

Willis was a groundbreaking lenser who changed the look of films with "The Godfather." As reported in the '70s film history "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," when Willis shot "The Godfather," many of the scenes were very dark, to the point where the studio, Paramount, wondered if the audiences would even be able to see them.

In that era, films were brightly lit so they could be seen in drive-ins, but Willis followed his own vision, and it changed cinematography forever. (As the documentary "Visions of Light" explains, Willis was eventually nicknamed "the prince of darkness.")

Willis shot six films for Pakula, yet he remarkably never won an Academy Award until 2010, when he was given an Honorary Oscar for decades of great cinematography. Willis died on May 18, 2014 at the age of 82.

Willis used the language of cinema to convey good and evil

One thing that has become less frequent in modern filmmaking is the language of cinema, where directors employ cinematic shorthand techniques of editing, lighting and cinematography to speak volumes about the story that no dialogue could cover. Pakula and Willis really understood the importance of this, and harnessed its power with the paranoia trilogy.

Willis initially used the language of cinema on "The Godfather," where he used the contrast between light and dark photography to convey the shifting contrasts between good and evil. (One of the reasons Brando is darkly lit in "The Godfather" is Willis didn't want audiences to see what was going on in Brando's eyes.) Also, note how Al Pacino is lit differently as his Michael Corleone increasingly embraces his darker tendencies.

Willis also utilized such lighting contrasts in "The Parallax View" and "All the President's Men." In a 2004 interview, Willis called it "visual relativity," adding "I like going from light to dark, dark to light, big to small, small to big."

In an archival interview, Pakula said that with "Klute," he "wanted to get a sense of a claustrophobic world. I wanted to get that sense of compression and I wanted to play with scale, to get an inhuman scale, people feeling trivial, losing their sense of identity." In the scene where Jane Fonda is introduced in the film, for instance, Pakula decided to put gigantic fashion photographs on the wall above to make her look tiny.

Fonda spent time with sex workers for her role in Klute

"Klute" was the first film in Pakula's trilogy, and it dealt with a detective played by Donald Sutherland who is investigating a murder; and a key to the case was Bree Daniels, a prostitute played by Jane Fonda.

In playing Daniels, Fonda researched the role by spending time with real ladies of the night. As she recalled in an interview for The Criterion Collection, Fonda realized that after spending somewhere between 7 and 10 days with them, "The thing that struck me about the call girls in particular, there was no light in their eyes. It was like their soul had been taken out of them."

Fonda also noted that while doing this research, "not one john even winked at me!" She later told AFI she wasn't sure about taking the role, and didn't think she could do it, but as she and Pakula got deep into their research, they examined the sexual abuse that prostitutes had suffered.

Near the end of the film, a pivotal moment arrives when Fonda cries in a haunting scene, letting all her character's past experiences pour out. She later recalled, "I don't think I would have cried that way if I wasn't already becoming a feminist. I cried for women who are abused."

Fonda was coming off "Barbarella" at the time, and she didn't want to have long blonde hair to play Daniels; sitting in a stylist's chair, the classic, short brunette look was conceived that would become a major trend.

Fonda won her first Oscar for Klute

As Fonda recalled in a 2019 interview for the Criterion Collection, before she took on the role of Daniels, "I was just beginning to understand feminism. It was becoming part of my thought process... [I thought] if I'm a feminist, I can't be a prostitute."

But then a friend of Fonda's convinced her to take the role, telling her, "This script gives you a chance to go deep, and if you can go deep into any human being, that is feminism...it allows you to show an entire human being."

While she had some misgivings about taking on a dark role, Fonda won her first Academy Award for "Klute." She told Healthy Living, "I thought that it was going to happen...It's in the air...I was expecting it." While Fonda was dedicated to her activism, she didn't get political when she won, telling the audience, "There's a lot to be said and tonight isn't the night."

Once she won, Fonda walked off the stage, and began to cry "because it seemed so wrong that I would win the Oscar before my father."

Fonda would soon win her second Oscar for the Vietnam war drama "Coming Home," and she finally was able to present her father, the legendary Henry Fonda, his sole Oscar for "On Golden Pond," which she called "one of the happiest moments of my life." Henry Fonda would pass away five months later.

The paranoia trilogy was an influence on David Fincher

Among modern filmmakers, David Fincher is considered one of the best, hailed for his dark, uncompromising visions in films like "Zodiac," "Fight Club," Se7en" and the acclaimed serial killer series "Mindhunter." It might not be a surprise, then, that his dark projects (visually and thematically) have been significantly influenced by two of his favorite movies, "Klute" and "All the President's Men."

In watching "Klute," it's clear that it was a big influence on "Se7en," and you can also see how "All the President's Men" was an influence on "Zodiac." Both are detective stories, and both emphasize how much research and investigative work it takes to solve a crime — also a key point of "President's Men."

As critic Zach Vasquez puts it, "Klute" can be compared to "Se7en" because "it is the story of a detective's search for a killer amidst New York's underworld flesh trade. Like 'Se7en,' it involves a pair of mismatched investigators stumbling their way through a world shrouded in darkness — both figuratively as well as literally. Pakula's thrillers are all set in a world of omnipresent shadow and night, and it's in them we find the biggest influence on Fincher's own aesthetic."

Vasquez also feels that the film "that casts the largest shadow over 'Zodiac' is 'All the President's Men.' Fincher mirrors the obsessive, spooky and surprisingly funny mood and style of Pakula's film, to say nothing of their similar period setting."

Why the recruitment test scene in Parallax transcends

It's an incredible, vastly under-appreciated scene in cinema history. In "The Parallax View," Warren Beatty, playing a reporter trying to uncover an assassination, is sitting in a chair. Beatty is shown a series of images, and a voice over a loud speaker tells him, "Just sit back, nothing is required of you, except to observe the visual materials that are presented to you."

A series of images flash past his eyes. Past presidents, the American Flag, people living in poverty, people rioting and being beaten by police, the Statue of Liberty, money, the Klan burning crosses, Hitler, along with words like LOVE, MOTHER, ME, HOME, ENEMY, COUNTRY and GOD. At the conclusion, the ominous voice announces, "Please proceed to our offices. Thank you for your cooperation."

It's an incredible segment that shows how an evil organization is trying to brainwash Beatty, then gauge his reactions to what he's seeing.

Esquire hailed it as "The best scene in the best conspiracy thriller ever," and as John Semley wrote in 2013, "The sequence nicely captures the confusion of post-Kennedy America, where the meaning of long-held values of family, patriotism, and self-worth had been tossed to the wind. It represents the flickering mental state of a nation whose search for meaning at times felt meaningless, when the very foundational ideas of nationhood had been yanked loose from their longstanding connotations."

Towne's twin paranoia classics

Another great classic of '70's cinema is the dark noir thriller "Chinatown," starring Jack Nicholson. That film was written by Robert Towne, considered one of the best screenwriters in Hollywood history; he also reportedly did some polishing on the "Parallax" script.

In addition to Towne's best-known works, from "The Last Detail" to "Chinatown," he worked behind the scenes as a script doctor on a number of instant classics, including "Bonnie and Clyde" and "The Godfather."

While it's been widely reported that Towne worked on the "Parallax" script, according to the '70's film history "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," it was top secret because he was allegedly working on it during the Writer's Strike, and if anyone found out about it, the Guild likely would have imposed a stiff fine on Towne. As it stands, "Parallax" is an adaptation of a novel by Loren Singer, and the credited screenwriters on the film are David Giler and Lorenzo Semple Jr.

"Chinatown" is considered a '70s classic of paranoia as well, and it isn't hard to find the similarities. As Chris Hewitt of the Star Tribune writes, "The voyeuristic 'Chinatown,' while not set in the post-Watergate years, is also clearly a product of them... paranoid conspiracy thrillers are the answer to the film noir of the '40s, equally dark tales that also focused on lone wolves attempting to solve mysteries that were bigger than they realized."

Robert Redford pushed to turn All the President's Men into a film

Leading man Robert Redford had just came off a political film (the acclaimed 1972 dark comedy "The Candidate") when the Watergate break-in occurred. On the 35th anniversary of the movie, Redford spoke at the LBJ Library, and he told the audience, "Since I already had issues with Nixon, I was very primed to see something not go right with him."

Redford kept waiting for the news to pick up on the break-in, and eventually he saw a small story written by two guys whose names he didn't recognize. He then kept seeing their bylines throughout the Watergate crisis. Looking into Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, he was fascinated by their divergent personalities, and how they had to work together despite their differences in style and technique.

At first, Woodward and Bernstein were cool to the idea; Redford finally called Woodward, and the two-time Pulitzer-winning journalist didn't think it was really Redford on the phone. "We thought we were being set-up," Woodward later recalled. "We knew we were being watched, we were paranoid and frightened."

Redford had to play Woodward to get the movie made

When Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman played Woodward and Bernstein respectively, it made both reporters household names, and people would often confuse the real-life newsmen for their big screen counterparts.

Yet, as Redford would later recall, he initially didn't want to play Woodward in the film version of "All the President's Men." Warner Bros. was initially wary about making the movie. Watergate was a national ordeal, the details were quite well known, and the studio feared that by the time of release everyone would want to get past it.

"The way I was able to push through that was to say, 'It isn't about Nixon, it isn't about the national event," Redford recalled. "It's about what these guys did that other people weren't doing underneath the story that everybody knows."

Ultimately, it was the star power of Redford that got the greenlight — even if the star was reluctant to accept it. "I did not want to be in the movie," he said. "I thought that would distract, because these guys were unknowns and they should be played by unknowns."

Warners finally told Redford they'd buy the rights, but he had to be in the film. Once Redford agreed, he brought in Hoffman, and the big screen incarnation of Woodward and Bernstein was born.

The paranoia trilogy proved journalism movies could work

Before the success of "President's Men," journalism was considered a boring profession that wasn't movie-friendly. Then Woodward and Bernstein became household names, and journalism suddenly became glamorous, heroic and exciting.

Redford initially envisioned the Woodward and Bernstein saga as a small story, but the big screen success of "All the President's Men" proved that a movie about a stuffy profession could make a tau, and successful thriller. Political dramas were also usually not hits at the box office at the time; again, "All the President's Men" broke tradition.

According to Box Office Mojo, "All the President's Men" made $70 million, a substantial gross for 1976 and fourth highest grossing film of the year. It also won four Oscars including Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Sound, Best Art Direction, and Best Supporting Actor for Jason Robards, who played legendary Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee.

"President's Men" also received strong reviews, with the New York Times noting, "Newspapers and newspapermen have long been favorite subjects for moviemakers... yet, not until 'All the President's Men' has any film come remotely close to being an accurate picture of American journalism at its best."

The paranoia trilogy films are still relevant today

While all 3 of these Pakula films are '70s classics, they remain relevant and powerful today — perhaps more so than many of their contemporaries — in a social media and internet-fueled age where rumors, conspiracy theories and paranoia spread like wildfire.

Newer cinema fans write about these films with reverence; one recent retrospective of "The Parallax View" called the film "a chilling tale with modern-day repercussions... Strip away Beatty's bushy hairstyle and a few noticeably '70s touchstones, this hasn't aged but has actually become more probable and relevant than ever."

A modern review of "Klute" for the AV Club called it "a sharply feminist drama in the shadows of paranoid noir... peeking through the dark shadows of manly intrigue and underground malaise is the deeply personal story of a woman whose inner life stands out against the dull violence of her surroundings."

CNN felt similarly, observing recently that decades after its initial release, "All the President's Men" with its "crackling plot, excellent performances, and as-it-happens immediacy still make the film one to watch."