Cultural Critics Looking For A Political Agenda In Yellowstone Are Missing The Point

The argument that Taylor Sheridan's "Yellowstone" has fully established itself as prestige TV for the conservative viewer, as framed by TV Guide, is abundantly clear — the creator's ongoing refute of this reality notwithstanding. After all, the show's central protagonist is a wealthy, white rancher fighting the good fight against progress and retribution, and though Sheridan told The Atlantic's Sridhar Pappu that the show was really about exploring the idea of kingdom and morality (e.g.,"does morality factor into the defense of the kingdom? And what does that make the king?") the series made its Royalist thoughts on the latter abundantly clear long ago. The show's success in the South and Midwest (per Paramount) is a surprise to no one, and the "life imitating art imitating life" impact its success has had on Montana (per CNBC), while almost too perfectly ironic, was as predictable as a certain Dutton storming away from the dinner table at least once an episode.

And yet, for all its abject conservatism, the efforts of "Yellowstone" to appeal to and appease a wider range of viewers — successful or not — in Season 1 and part of Season 2 are worth considering. Now, to be clear, as a liberal apology for a series that slid (and continues to slide) so far to the right of its starting point, those efforts fail entirely. But the timing of when — and the speed at which — those efforts fell fully by the wayside speaks directly to the straightforward and wholly unromantic agenda upon which Sheridan ultimately settled. That is: defending, expanding, and promoting the kingdom of "Yellowstone."

Sheridan read the room early on

In "Yellowstone" Season 1, the series attempts to position itself as having, to some degree, the same implied thesis and perspective as any number of critically-beloved power struggle plots, wherein the morality of the work itself differs from the morality of its power-hungry or hoarding characters. The distinction is soft and inconsistent, but it served to give the story a thread of plausible deniability with regard to its ideology.

Initially, the irony of rich, white landowners making a desperate last stand on stolen land — against, in part, the very people from whom it was stolen — was very present, and even integral to the story and its narrative tension. But as The Guardian's Adrian Horton explores in-depth in "Yellowstone: the smash-hit TV show that exposed a cultural divide," both the series' placement on basic cable (whose audience skews older) and its core themes (e.g, home and land ownership) ensured its popularity with, as Horton writes, "land and business-owning local elites in smaller markets across the country, whose politics tend to skew conservative."

Thus, the room revealed itself, and so did the series' agenda — an agenda that remained the same, even as the show's clearly-motivated decision to drop this undercurrent of irony adjusted and locked-in its ethos.

Season 1 played its politics closer to the vest

In Season 1, the series plays it safe. We get several references to the benefits of running as an Independent, including John Dutton (Kevin Costner) insisting he won't let his son Jamie (Wes Bentley) run for office as a Republican, and Governor Perry (Wendy Moniz) saying, "He would run as an Independent. That way he has something to offer both sides."

Not that those sides matter. As we're reminded on just as many occasions, Jamie's focus is simply doing the bidding of his "constituency of one" (aka, John Dutton). Of course, the series can't get around the fact that Costner's patriarch, for all his enthusiastically reiterated lack of party allegiance, wants to maintain the status quo — a conservative motivation by just about any standard.

Instead, it tries to keep that status quo and its various opponents (e.g., Californians) grounded in Montana's divide and isolated from national issues, offers us a Dutton dissenter in the form of Luke Grimes' Kayce, and brings balance to the ranch storyline with Gil Birmingham's Chief Thomas Rainwater, the Long family, and the Broken Rock Indian Reservation. The reservation scenes are filmed on the Crow Indian Reservation, where Sheridan sought approval and guidance from Crow Nation tribal chairman AJ Not Afraid and local advisory teams (via Variety). This balance couldn't negate the conservative appeal of the series' central family, their implied politics, or the reality of how their ranch came to exist. But it does, in light of where the series currently stands, reveal something about its evolution.

Remember when Monica existed?

Lest anyone think "Yellowstone" has simply become more subtle about weaving in progressive pushback, it's worth taking a look at one of its (currently) least utilized characters. Early on, Kelsey Asbille's Monica repeatedly highlights the irony of the Duttons' worldview and mission. In Season 2, Episode 2, Monica delivers an introductory lesson on power dynamics and the European mentality. "What you know of history," she says to her class, "is a dominant culture's justification for its actions. And I don't teach that."

The episode, and two others in which Monica not-so-subtly exposes the Duttons' essential storyline via cultural field trips, aired in the summer of 2019. A little over a year later, then-president Donald Trump issued a memo calling Critical Race Theory — as imagined and portrayed by conservative scholar Christopher F. Rufo — "divisive, anti-American propaganda" (via The New York Times). Frankly, we don't see enough of Monica's curriculum to try and define it. But at the start of her arc, it's clear the series intended for her character (and this is about the character, not Asbille, whose casting prompted its own controversy) to reiterate, relay, and represent certain themes that called the Dutton narrative into question.

How well it accomplished this goal is its own debate. What's clear is that after Season 2, we never see Monica lecture again, and we've yet to see her in a position of power again. Of course, correlation doesn't necessarily imply causation. But the fact that the show's apparent use (or lack there-of) for Monica has changed so dramatically — and in such vivid alignment with conservative fan vitriol, per Outsider — is difficult to ignore, particularly since the original version of Monica provided some of the series' most important narrative tension.

Yellowstone went all-in on its king's perspective...

In "You're the Indian Now" (June 2020) Monica is given some telling dialogue, none of which lines up with the character we first met, and all of which marks the series' ultimate shift. "When this land belonged to my people 150 years ago," she tells John after Tate (Brecken Merrill) is kidnapped and retrieved, "children were stolen, men were killed, families herded away like cattle. And nothing's changed. Except you're the Indian now."

Except, of course he isn't, for so many, many obvious reasons. But having her character deliver that line — without, importantly, even a hint of irony or sarcasm — gives those viewers who might have some lingering reservations about rooting for the Duttons the freedom to go all-in.

From there on out, the series continues to draw parallels between the two, even having John repeat, almost verbatim, some of Chief Rainwater's lines from Season 1. Both characters say they're "the opposite of progress," and both characters note the difference between "what's legal and what's right." Chief Rainwater is given these lines in Season 1, but John Dutton doesn't deliver them until Seasons 4 and 5, and the mirroring isn't there to highlight a now long-dead thread of irony. Instead, it's there to quietly reinforce the idea that the Duttons are the new victims of colonization (and gone are the moments, like we get in Season 1, of Rainwater saying things like, "You people don't know the concept of victim").

...and on a specific fantasy

In Tressie McMillan Cottom's breakdown of "Yellowstone," its viewership, and the mechanics of how its conservatism plays to that viewership for The New York Times (titled "A Big TV Hit Is a Conservative Fantasy Liberals Should Watch"), the author examines the series through, "the asymmetries in how liberals and conservatives consume cultural objects." While she observes that "it is too easy to call it a conservative show," her exposure of why it's too easy rejects the notion that "Yellowstone" has some underlying progressive motive. "Whatever brings its audience to the show," she writes, "once they arrive, they are playacting within the vision of America that 'Yellowstone' holds. The show suggests that elitism and power can be reconciled with our need to be both moral and self-interested. It is a seductive fantasy because it does not ask the audience to give up anything."

That reality is part of what makes it so tempting to seek out progressive aspects within "Yellowstone," as so many examinations of both the show and of Sheridan's thoughts on the series, have done. For instance, a piece in The Hollywood Reporter reads, "'Yellowstone's' portrayal of land-use politics in the western U.S. — particularly their effect on the Native American characters — is a Trojan horse, a political subtext hiding within a melodrama," while a Vanity Fair article that explores the show's conservative fantasy also notes "it's obvious that ["Yellowstone"] believes our history's ideology and laws are deeply encoded with racism; it also thinks things won't always stay this way. Watching the series, its conservative viewers are forced to face their biggest fears, whether they realize it or not."

Yellowstone's increasing success is no surprise

While these observations apply to the romantic idea of what "Yellowstone" might hypothetically have become, both that subtext and that obviousness — that line between what the work thinks about the Duttons' perspective and the Duttons' actual perspective — haven't existed for the majority of its run. And its erasure refutes the idea that in inviting conservatives who relate to John Dutton to more easily swallow the irony of his situation (by comparing his, and by extension their own, conflicts to those of Native characters), the series is somehow "secretly" incorporating a liberal agenda (as does, to an even greater degree, the fact that the series does offer "white grievance that you can feel good about," as McMillan Cottom explains in an interview with Vulture).

Once "Yellowstone" found its inevitable actual audience, the imagined audience no longer mattered, but the idea of a conservative viewer's "biggest fears" sure did. And although fear can and often does function as a vehicle for social commentary or furthering an agenda, "Yellowstone" has little interest in the self-awareness such functionality requires. It's the justification of that fear (of rampant social anxieties about a changing way of life), that "Yellowstone" utilizes, and while there's no defined political agenda behind Sheridan's flagship series (it doesn't need one) there is this: the more a viewer empathizes with a particular fear, the scarier its portrayal is; the scarier something is, the harder it is to look away; and the harder it is to look away, the more money the thing being looked at pulls in.

The series is committed to its fandom

After its early attempt to distinguish its worldview from that of John Dutton, "Yellowstone" (or so the shift in its writing would suggest) quickly realized that Fear A (losing one's way of life or property to progress and development) was a more tangible, immediate, and compelling threat to much of its audience than Fear B (the less tangible notion of acknowledging an irony). Thus, A remained, and B more or less disappeared. By Season 5, John Dutton has even won over Monica, his last remaining dissenter, in a move that did not go unnoticed by fans. Again, the shift reveals that there's certainly an agenda at work here, but it has very little to do with pushing politics, despite its reaping the rewards of established allegiances.

Unlike the weak, over-educated Jamie, "Yellowstone" never had a constituency of one. And despite Sheridan insisting that his only loyalty was to "responsible storytelling" — which it may well have been in those halcyon days before the ever-expanding gap between the (outspoken and largely liberal) critical response to the series and that of its (equally outspoken and largely conservative) fandom revealed itself — it seems that, in the end, the series' main concern was not to its story (insomuch as there even is one anymore), but to appeasing its constituents, as we learn in "Watch 'Em Ride Away."

The episode isn't so much an installment in the narrative as it is Sheridan making it known, once and for all and with comedic clarity, for whom the series is officially and exclusively written. In place of a plot, viewers are treated to a sequence of smirks.

Season 5, Episode 5 thumbs nose, waves red flag

First up, we get Beth's (Kelly Reilly) speech about greedy environmentalists. Next, we're given the "new and improved" Monica — whom fans have long criticized for being "mopey," a "burden," or "ungrateful" (read: traumatized, rational, and aware) — happily swooning over her gaslighting husband. She smiles, she laughs, she makes nice, and by the end of the episode, the most we can hope for Monica is that she didn't feel any pain during her off-screen lobotomy.

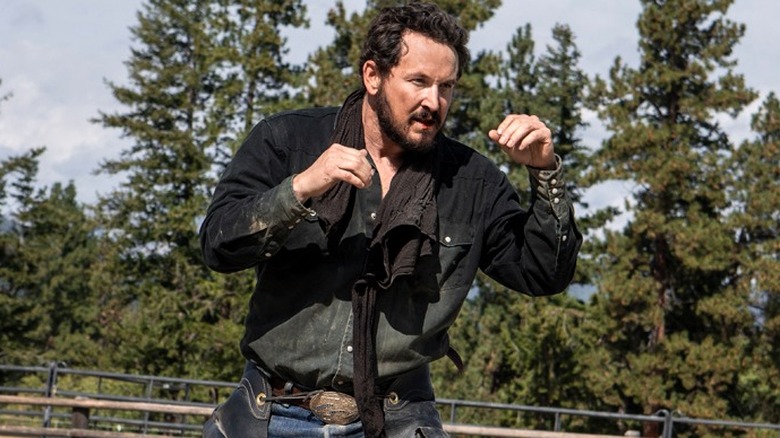

Finally, there's Piper Perabo's Summer, a cartoon vegan who — despite being a second-generation omnivore and Nature Lover — is shocked to learn how cows digest grass, doesn't know how forest fires start, struggles to comprehend the most basic analogies, verbally attacks her hosts, and may or may not know how to convert oxygen to carbon dioxide without John Dutton's guidance. She exists solely to forward an increasingly frequent theme of the series — that if you don't agree with the Duttons, it's because you don't understand what they do — and when Beth takes her out back for a good 'ol fashioned blonde-on-blonde fist fight, the Rational Man of The House (Cole Hauser's Rip) has to play the parent.

The entire episode is Sheridan speaking by-proxy through his characters, but the icing on the cow pie is Rip's take down of Summer's liberal snobbery, in a speech that almost perfectly mimics Sheridan. "You should be mindful of not berating the subject you are trying to educate," the writer and director said in the aformentioned interview with The Atlantic." Rip's version is simpler: "You're never gonna convince someone to think the way that you think by insulting them in their own house."

And "Rip" has another, potentially more telling point to make: "You don't like the food, don't ******* eat it."

Sheridan's approach is paying off

Whatever its initial intentions, "Yellowstone" — a story that takes place in a red state and revolves around a white rancher — premiered two years into the Trump administration, and blew up during a pandemic that proved even basic public health precautions could be violently polarizing, while at the same time keeping people indoors, on couches, in front of TVs, and on social media. Over the years, it's wooed millions and millions of largely conservative viewers while simultaneously prompting liberal outlets to go from panning it or writing it off as a messy soap opera (such as THR and IndieWire) to analyzing its politics and agenda as they impact its reputation and Emmy odds (also THR). By losing the irony and keeping things firmly ideologically conservative, Sheridan has thus been able to kill two profitable birds with one big, red stone. Obviously, the behind-the-scenes agenda of all series is to renew and grow. But few have so directly and transparently relied on the political identity of their art and its viewership — as opposed to, for instance, the art itself — to further their commercial agenda.

In Season 4, John and Rip discuss betting the farm on the revered horse trader, trainer, and rodeo star Travis Wheatley, aka The King (Taylor Sheridan), and his ability to (like Sheridan) win big on the circuit while expanding the Yellowstone name.

"They made such a name for themselves you can buy a damn truck with their brand on the seat," John says of Travis' Bosque Ranch empire before adding, "outside this valley who knows we're even here? I'm gonna let the world know we're here." He wants to put Travis on the road for Yellowstone, but as the cocky cowboy reminds him, you gotta spend money to make money.

...and Yellowstone is riding the red wave all the way to the bank

After telling a desperate John exactly how much it will cost to scoop up his prestige and all three of his cutters, Travis concludes with, "I'll get you the best of the best in all three, and I will stack checks on your desk thick as a ******* phone book."

The episode aired in November of 2021, roughly nine months after ViacomCBS announced their own pricey partnership with Sheridan (per THR) in an effort to expand the reach of Paramount+ and broaden its brand (per L.A. Times). "1883," "1923," and "6666" were all born from this partnership (bringing sum total of spin-offs, by 2023, to three), and given the universe's following, the millions of new subscribers Paramount+ has picked up, and the fact that Sheridan's writing and developing plate currently includes eight different series, it seems the conglomerate's gamble to take Travis... er, Sheridan, up on his costly pitch is paying off. And it is, in no small part, thanks to the pair's pragmatic fanbase loyalty, both in-world and out (via The Wrap).

In the end, and as always, it's our intrepid ranch hand Rip who says it best: "That ****** doesn't do anything but win, Sir," he tells John of Travis. "He puts the ***** in horse trainer. But if he's ridin' for the Y, he'll be true to it."