Emancipation: The 6 Best And 6 Worst Things Ranked

"Emancipation" tells the true story of the runaway slave Peter (Will Smith), who, as the movie begins, is ripped away from his wife Dodienne (Charmaine Bingwa) and children and taken to a new plantation. As the story goes on, Peter, upon hearing the news that slavery has been abolished, decides to make a break for Lincoln's soldiers located in Baton Rouge. As he makes his way through the treacherous Louisiana swamp, he encounters countless obstacles, all while being relentlessly pursued by a cruel slave hunter named Fassel (Ben Foster).

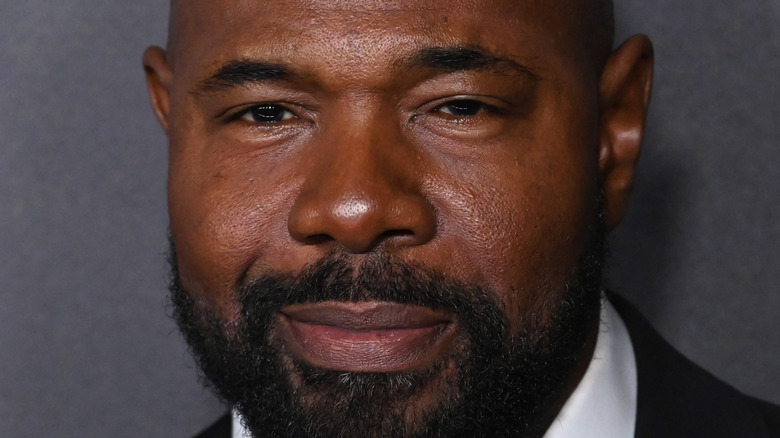

It's a story rife with seemingly insurmountable obstacles and brutality, all to recreate the horrors of slavery and provide a testament to the courage of those like Peter. Unfortunately, in the hands of director Antoine Fuqua and writer William N. Collage, "Emancipation" is largely a bust of a movie, one that fails to make a motion picture worthy of its real-life subject.

That's not to say "Emancipation" is devoid of worthy elements, however. The actors, in particular, turn in commendable work that often lends more depth than what's in the script. However, "Emancipation" is constantly weighed down by baffling decisions, including its peculiar cinematography and a lack of personality allotted to its supporting players. Breaking down the best and worst things in "Emancipation" makes it clear that this feature has brutality to spare, but also how far it misses the mark.

Best: Will Smith's physicality

Throughout his career, Will Smith has been a performer who has garnered much of his fame from his vocals. Whether it was his comedic line deliveries, his singing skills as a rapper, or even forays into voice-over work, Smith's greatest moments have come from his lips. But the physical qualities of Smith have often been just as crucial. Beyond having the handsome looks of a leading man, Smith has frequently demonstrated a gift for knowing just when to accentuate his body language to sell the punchline of a joke, something he displayed memorably in films raging from "Hitch" and "Independence Day." A more dramatic film like "The Pursuit of Happyness" saw Smith using this physicality to sell the personality of a father who will never stop chasing his ambitious dreams.

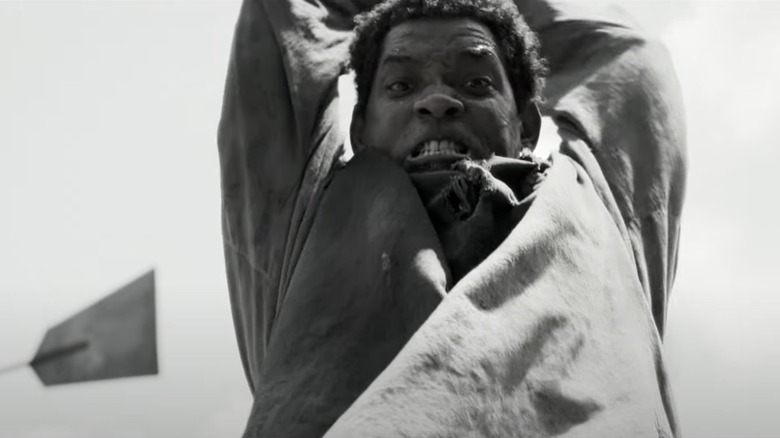

For "Emancipation," Smith gives the character of Peter a sense of physicality that's quietly complicated and admirably different than that seen in his prior performances. Through Peter, Smith adjusts his gait and body language to reflect a man who has been beaten down for decades; you can feel the aches in his bones as he moves hurriedly. Simultaneously, Smith also conveys perseverance in Peter's posture and stance. He's a person with pain in his soul, but also the tenacity to stand up against oppressors. It's a unique combination that doesn't recall prior Smith performances, but does speak to how superb he remains as a physical performer.

Worst: The emphasis on pain over characterization

"Emancipation" does not flinch in depicting the brutal horrors inflicted on Black slaves by white slaveowners. As Peter is brought into his new home, he sees the heads of Black men stuffed onto the tips of spikes surrounding the entrance of this domicile; shortly thereafter, a slave who attempted to flee is branded by his owners. An important thing to note here is the lack of names or discernible personalities given to the human beings who experience all this suffering. They only exist to depict anguish on-screen, their lives only garnering purpose in the eyes of "Emancipation" as a film whenever it's time for Black people to endure enormous torture on-screen.

Even once the film's cast is stripped down to just Peter and a handful of other slaves running away from captivity, screenwriter William N. Collage struggles to develop discernible personalities for the minimal characters steering the story. The goal of all this on-screen suffering is clearly in service to "Emancipation" emphasizing the horrors committed against Blacks, a reality that, along with countless other aspects of systemic oppression against the community, is too often erased in modern America. However, the staunch refusal on the part of "Emancipation" to flesh out these characters who are being branded, whipped, shot, and all other manners of tortured just leaves the film feeling hollow, not impactful. The characters depicted here deserve better than being reduced exclusively to their suffering.

Best: Charmaine Bingwa's performance

Though her screentime as Peter's wife Dodienne is limited, Charmaine Bingwa makes great use of what time she does get in "Emancipation" to deliver a rock-solid performance. In fact, she gets to deliver the best piece of acting in the entire film in a scene depicting Dodienne awakening in the middle of the night after having a nightmare about her husband. Set against a pitch-black backdrop with the camera lingering on just her body from the shoulders up, Bingwa's face communicates anguish and heartache without the aid of hand gestures or excessive amounts of dialogue. This moment, communicated in largely one unbroken take, is well-realized in the hands of Bingwa, who does commendable work wringing a ton of emotion while giving a restrained performance.

The rest of Bingwa's screentime in "Emancipation" doesn't give her anywhere near as substantial a load to carry, but she still manages to do what she can. A scene where she portrays Dodienne learning that she is being sent away to a new husband and away from her children, for instance, makes great use of her gift for haunted facial expressions and quiet displays of torment. Charmaine Bingwa's work in "Emancipation" is so good, in fact, that it deserves a more consistent, engaging film around it.

Worst: The cinematography

Director Antoine Fuqua and cinematographer Robert Richardson filter the world of "Emancipation" through a very specific visual style. Color is largely drained from the feature, though not to the point of the entire movie being realized in black-and-white. The hue of the movie is largely grey more than anything else, with occasional bursts of color (such as green in patches of grass, or blue dominating the frame in nighttime sequences) making their way into the "Emancipation" visual scheme. It's a bold concept on paper and, in the hands of a legendary cinematographer like Richardson, could've resulted in something extraordinary.

Unfortunately, all this visual style does is make "Emancipation" look dreadfully murky. The dimly-lit visual approach rarely suggests much in the way of a distinctive filmmaking voice, mostly because the thought process behind when certain colors are present or absent from the film comes off as erratic, at best. As demonstrated by countless directors (just look at the black-and-white works of Akira Kurosawa), draining the color from your movie can result in striking images that can potentially make great use of elements like shadows. Unfortunately, the "Emancipation" sense of staging and framing is always quite unimaginative, never taking advantage of the opportunities presented by its limited color scheme. While a bold choice in theory, this visual choice ultimately does nothing for the movie.

Best: Depiction of racism in Northern forces

The most interesting facet of Collage's screenplay comes when Peter is finally in the hands of Union soldiers. This is what he's been running towards the entire movie, it should feel like a triumph. However, "Emancipation" makes an intriguing swerve in depicting these would-be saviors as far more complicated figures.

Upon talking to a high-ranking official in the Union camp he's healing in, Peter learns that his options are now limited to either doing manual labor or being a soldier in the Union army. There is no other route for Peter, as this man's cries for help in retrieving his family fall on deaf ears. Rather than fleeing the South to find a wealth of prosperity and options, Peter has now found himself at the mercy of other white institutions who want to exploit him.

This complicated portrait of Union forces extends to the scene where a military general remarks upon Peter's "scourged back" photo depicting the various wounds this man received from the lashes of slave owners. This general notes that he sees these injuries only as evidence of Peter being "disobedient." The constant dehumanization of Peter, and dismissal of his worries, shows that the minimizing of Black people was all over America in this era rather than just confined to one region. This makes for one of the most subversive, sly pieces of commentary in "Emancipation," and it helps up the stakes of Peter's journey considerably.

Worst: Giving Fassel a backstory

Roughly midway through "Emancipation," Fassel and his cohorts, after a long day of chasing after Peter, settle down for the night in a tranquil part of the swamp. Upon hearing somebody dismiss Black people as innately stupid, Fassel begins a long monologue expressing his belief that Black people are actually smart, scheming, and determined to take over America. This whole speech hinges on a friendship he struck up with his Black nanny as a child. It was a dynamic that his father brutally opposed (he eventually killed the nanny), and the experience instilled in Fassel some disturbing ideas about the value of Black people.

Ben Foster has some good line deliveries and subtle bits of physicality in this sequence, but those qualities are never anywhere near enough to get one to wonder why on Earth "Emancipation" is bringing its story to a screeching halt to flesh out the backstory of a slave-hunter antagonist. While every Black person in this movie, save for Peter, never get to be defined by anything more than their pain (most don't even receive names), Fassel gets a grand speech explaining his worldview. The strange visual priorities of this sequence, which quietly reinforce the "importance" of Fassel by focusing on a tight close-up of his face (contrast that with "Tar" or "Red Rocket," which have dialogue from privileged characters set against shots of the faces of the marginalized), just hammers home how bizarrely conceived this entire sequence is.

Best: Not just focusing on the scourged back photo

Peter's lasting legacy in our modern world is as "whipped Peter," remembered via the "scourged back" photograph, which depicted the various wounds on his back that he endured from slaveowners. In the eyes of some, that photo dating back to his 1860s escape is something akin to one of the first viral images, and it has opened the eyes to multiple generations as unpolished evidence of the brutality of slavery.

By utilizing the then-new advent of photography, the experiences of Black people in America were finally being put on display. Such historical significance makes it understandable why "Emancipation" would want to chronicle the life of Peter.

Thankfully, the screenplay, on a conceptual level, opts to not just focus on the "scoured back" photograph, nor define Peter by it. In fact, the first two-thirds of "Emancipation" features no trace or tease of this historical set-up (beyond a moment where Fassel whips Peter's back, hinting at where so many of this man's injuries lie), instead focusing on fleshing out Peter beyond just the one image.

Even the sequence depicting Peter finally being photographed makes sure to emphasize his autonomy as a human being (he remarks that he can move his arms himself without any help from white people), rather than solely defining him by an image. The basic structure of "Emancipation" admirably attempts to emphasize that while the "scourged back" photograph is a key part of Peter's legacy, it does not solely define his legacy.

Worst: Fuqua's use of slow-motion

Director Antoine Fuqua is a filmmaker who has engaged in prolific dramas before "Emancipation" (namely the 2001 feature "Training Day"), but his primary focus as an artist has been in the world of mainstream-friendly action movies. Whether it's the "Equalizer" movies, "Olympus Has Fallen," or his "Magnificent Seven" remake, Fuqua has been a go-to figure for action films with plenty of explosions, memorable death scenes, and quippy one-liners. Some of those movies have been entertaining, others have been more forgettable, but the filmmaking tenets of such features, regardless of quality, aren't a good fit for the story of "Emancipation." Too often, Fuqua's directing style in this grim tale tends to lean back on the same tools he has employed in dispensable action flicks.

Rarely is this more apparent than in the recurring uses of slow-motion throughout "Emancipation." This feature is especially notable in the first-half of the story, where it's used to highlight particularly brutal acts of violence. Fuqua can't quite pass up the modern cinematic cliches of slow-motion, much like Zack Snyder or Michael Bay.

Overplaying moments like Fassel shooting a runaway slave (here, in extreme slow-motion) feels both ill-advised and gratuitous. Isn't the content of the moment powerful enough to stand on its own?

Such rampant, derivative use of slow-motion throughout "Emancipation" is a prime example of how Fuqua's filmmaking here struggles to shake off the ham-fisted gimmicks that might work in an action movie, but come across here as a lack of trust in the material.

Best: The costume design

Francine Jamison-Tanchuck has had an incredibly eclectic career as a costume designer in the film industry, with her credits ranging wildly from "One Night in Miami" to "Glory" to "Garfield: A Tale of Two Kitties."

Her vast experience with period pieces means she was a natural pick for "Emancipation," and the costumes designed here are certainly one of the better elements of the feature. A particularly interesting element in her costume work is the subtle details that reinforce how often American society strips away identity from its Black citizens. For instance, in the early sequences set in the compound where Peter is held after he's taken away from his family, Jamison-Tanchuck's costumes for Peter and the other male slaves tend to use similar fabrics.

These men are wearing clothes they've been forced to wear, rather than outfits they've chosen, and the lack of variety in wardrobe is meant to be a reflection of how white oppressors strip these individuals of all traces of uniqueness.

A similar feat is accomplished in later sequences showing Peter as a Union soldier. These wartime outfits look pristine and sharp in terms of the materials used to realize them, but they too have been intentionally scrubbed of distinguishing characteristics. Peter and his fellow soldiers are largely thought of as mere cannon fodder, and those outfits reflect that. That brutal idea is well-realized within the apparent craftsmanship of Francine Jamison-Tanchuck's costume work.

Worst: The ham-fisted religious elements

The religious experiences of American slaves was incredibly complicated and, more often than not, revolved around a mixture of Evangelical Christianity and conventional core beliefs from the theologies of their assorted home lands. Such nuance is largely ignored in "Emancipation," which depicts Peter as a man who clings tightly to his Christian beliefs, constantly thanking God for his very existence on Earth. There's nothing wrong with this idea conceptually — especially since many Black men living in bondage in this era similarly strongly adhered to such beliefs — the problem is in its oversimplification.

Theological elements in the film come and go at random within the plot and are often forgotten about for long periods, so that the feature can function as a conventional survival thriller. There are also awkward moments revolving around Peter's faith, like a fellow slave (who has just been tortured for hours on end) hearing Peter's prayers and declaring that God doesn't exist. Despite having an understandable reason for his theological doubts, this character's behavior is played so broadly that he might as well be a "God's Not Dead" villain. Using religion as a way to explore how Peter coped with all the torment he endured could've been interesting, but the film's lack of faith in consistent, subtle storytelling undercuts this part of the feature.

Best: The expansive scope of Emancipation

Throughout "Emancipation," the viewer is constantly reminded, largely in moments where Fuqua's camera swoops around key environments in unbroken takes, the expansive nature of its canvas. Despite covering a historical figure that isn't quite a household name, nor being anything remotely resembling a conventional blockbuster, "Emancipation" has a grand scale to it. Given the film's reported $120 million budget, it's no surprise that "Emancipation" boasts several expansive, practically-built sets as well as tons of extras, lending an appropriate sense of grandeur to a third-act war sequence.

Seeing all this excess in pursuit of such a personal story can't help but make one wonder whether "Emancipation'" would have been better served with a more intimate scope. Still, in the modern filmmaking landscape, it is interesting to see so much money and resources being put into a kind of movie that isn't designed to sell Funko Pops or launch a cinematic universe. "Emancipation" as a whole leaves much to be desired, and features critical flaws that shouldn't be duplicated, but the notion of devoting lavish budgets to adult-skewing dramas is something Hollywood should embrace more often.

Worst: The film's lack of a larger point

"Emancipation" ends with some text playing out against a black screen, talking about how the "scourged back" photo of Peter had an enormous impact on America in the 1860s. The text goes on to note that the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery was put into effect in 1865.

Unfortunately, the phrasing here (likely unintentional) makes it seem like racism was solved after 1865; of course, it would only take on new, insidious forms in the years to come. The kind of horrors and dehumanizing viewpoints Peter contended with in the 1800s remain, and the disinterest of the film in acknowledging any sort of modern-day parallels speaks to how much the movie struggles to deliver any sort of meaningful thesis or reason for existing.

Lacking unique social commentary or insight into the historical events it chronicles, "Emancipation" is nowhere near interesting enough in its camerawork or editing to overcome that by functioning as a visual exercise. Its rudimentary, linear story structure doesn't allow any narrative risks, either.

Ultimately, "Emancipation" doesn't offer much to viewers except a rote retelling of certain historical events and a whole lot of extreme depictions of Black people in pain. Neither element is enough to give "Emancipation" a raison d'être, so it's no wonder the movie feels so lifeless and slight, a sensation that continues even through its end credits.