The Color Of Money: Facts About Scorsese's Hustling Hit That Don't Roll Funny

When asked to name a Martin Scorsese movie, most film fans will reel off the usual suspects: "Taxi Driver," "Raging Bull," "Goodfellas," "Gangs of New York." They rarely mention the overlooked gem that is "The Color of Money."

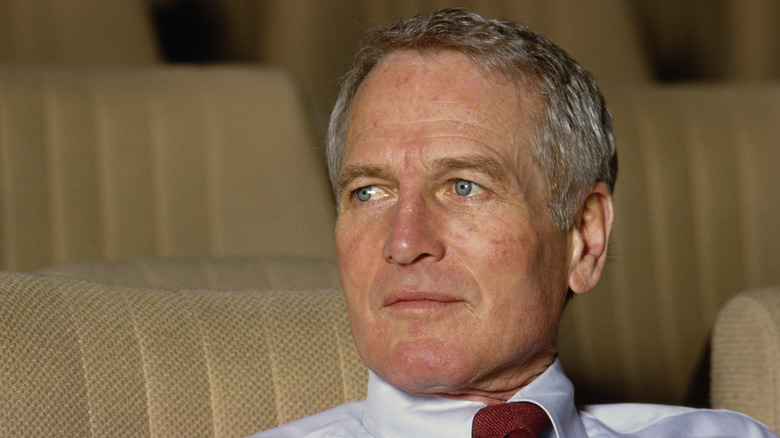

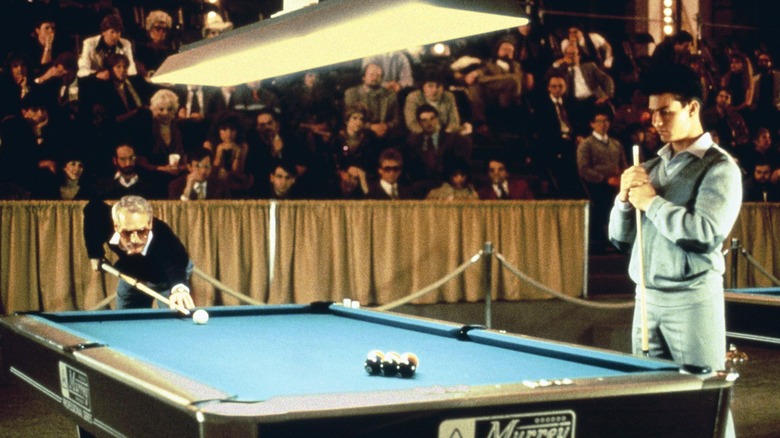

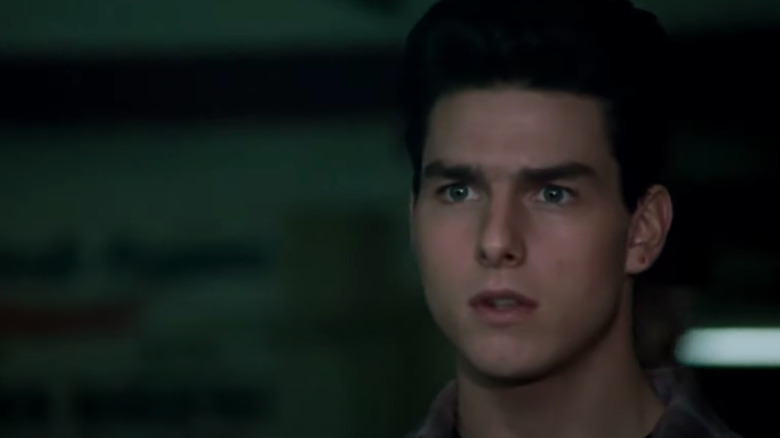

The 1986 movie about pool sharks on the make deserves a more prominent place in Scorsese's portfolio, not just because it features standout performances from Tom Cruise, fresh from "Top Gun," and Paul Newman, who won an Oscar for his portrayal of Edward "Fast Eddie" Felson, but because it hits as hard as a winning nine-ball off the break. "The Color of Money" is a legacy sequel to Robert Rossen's 1961 film "The Hustler." Yet it's very much its own beast and works just as well as a stand-alone movie about the intricate dynamics of relationships, greed, corruption, age, regret, redemption, hustling, and, of course, pool!

Pool is cool. That's not just an easy rhyme but a universal truth. And it doesn't get much cooler than when Paul Newman is sizing up a table with a glint in his eye and spouting lines like "Sometimes if you lose you win" and "Money won is twice as sweet as money earned." Although Cruise is on fire as the charismatic Vincent Lauria — who goes from a good-natured kid who just wants to "play to play" to a poker-faced hustler who can grift with the best of them — "The Color of Money" is about Fast Eddie and his search for salvation and the meaning of life in the dimly lit corners of America's pool halls. It's time to put the money down, rack them up, cue the action, and put the most interesting facts from "The Color of Money" back in the frame.

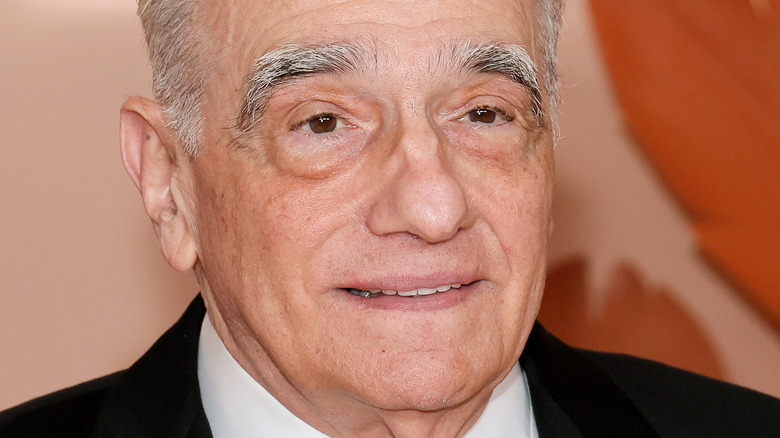

Paul Newman was adamant that Scorsese direct

"The Color of Money" was very much Paul Newman's passion project. The icon did all the legwork in getting the project off the ground, including getting in touch with Martin Scorsese and asking him if he would direct (via IndieWire). Like many people, Newman was deeply impressed by Scorsese's work on "Raging Bull" and believed its director was the perfect man to direct a sequel to "The Hustler." Newman told The New York Times that after reading Walter Tevis' novel, "It reminded me that Eddie wasn't completed at the end of the film like some other people I had played." Cinephilia and Beyond reported that because Scorsese was a longtime Newman fan, he overlooked the unsavory prospect of making a sequel to another filmmaker's baby.

Acclaimed New York novelist Richard Price, whose books included "The Wanderers" and "Bloodbrothers," was hired by Scorsese for script duties. The Director Series noted that with Tom Cruise, the star of "Risky Business" and "Top Gun," on board, things were looking promising. Scorsese explained that his ambition with "The Color of Money" was to make a Hollywood-style film. He added, "Or rather, I tried to make one of my pictures, but with a Hollywood star, Paul Newman. That was mainly making a film about an American icon. That's what I zeroed in on." Touchstone and Disney agreed to finance the film on the condition that if it went over its $14.5 million budget, Newman and Scorsese would be liable to make up the difference. With his salary and survival on the line, Scorsese ensured the shoot came in one day early and was under budget by more than $1 million.

Scorsese related to the self-destructive Fast Eddie Felson

Fast Eddie Felson is a complex character. Delivering boastful lines like "The best is the guy with the most" and "You gotta be a student of human moves" can make him seem more than a little superficial and obnoxious. Likewise, when he sets up Vince for a beating just to teach him to never go easy on his opponents, it offers insight into the more ruthless side of his personality. But when the same guy laments, "I'm too old, my wheels are shot," we know his bravado and bluster are masking an insecure soul who regrets some life choices and feels he no longer has skin in the game. An audience can relate to such a personality, and Martin Scorsese definitely could.

The outsider who lives on the fringes of society and is often the architect of their own downfall is the essence of so many Scorsese films. Fast Eddie Felson in "The Color of Money" is no different. In an interview with Midday, Scorsese explained that he was always interested in the Felson character and believes he was governed by the same forces as characters in other films of his, including "Mean Streets," "Raging Bull," "Taxi Driver," and "The King of Comedy." A streak of self-destruction that runs through characters like Travis Bickle and Fast Eddie Felson sees them sabotage anything good in their lives. That appealed to Scorsese. "My feeling," he said, "was the Eddie Felson character from 'The Hustler' was a guy who needed more than one or two lessons from life" before he could "come to terms with himself and reach some sort of peace."

Paul Newman gave Tom Cruise invaluable advice

In a sense, "The Color of Money" can be seen as a passing of the baton between the old guard and the new. Paul Newman represents Old Hollywood royalty, and Tom Cruise, whose fame was about to soar into the stratosphere with "Top Gun," was the cocky young challenger to the throne. The two actors' roles reflected their status in the industry at the time: Eddie Felson is the jaded old-timer who's seen it all and has nothing to prove; Vince Lauria is the wide-eyed newcomer, ignorant to the corruption all around him. Felson recognizes something in Vince and sniffs a shot of redemption. But Vince, who plays pool for pure joy but ends up using the game to pull the kind of cons that make Felson wince, proves to be more than an apt pupil.

As Cruise told The Uncool, "Newman sees this raw talent and thinks, 'Man, I'm going to make a lot of money off this kid.' He tries to turn Vincent into a hustler. They each act as a catalyst for the other. Eddie sees what he is missing." Cruise revealed on "The Graham Norton Show" that during filming Newman gave him some invaluable acting advice. He explained that during a freezing-cold Chicago January he was filming a scene where Newman was in a heated car and a warm coat while Cruise walked alongside in a T-shirt. Cruise explained, "He just looked at me and said, 'T-shirt? You tried your wardrobe on in the summer, didn't you?' And I said, 'Yes, sir, I did.' And he said, 'Watch and learn, kid. Watch and learn.' I never forgot it!"

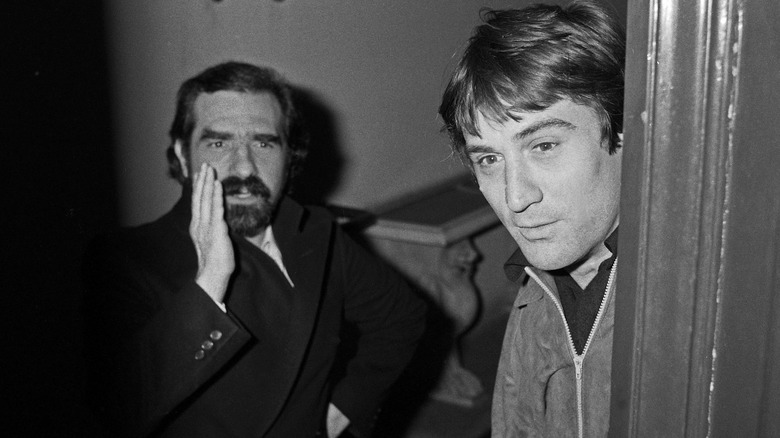

It was Scorsese's first time directing a major Hollywood star

Before "The Color of Money," Scorsese had never directed a household name before. His specialty was introducing the world to relatively unknown talents such as Robert De Niro and making them stars. According to The Directors Series, Scorsese had always wanted to direct a screen legend such as Paul Newman but while in pursuit of his artistic vision, he had always been too busy to make a full-blown Hollywood movie. When Newman contacted him out of the blue with a proposal to direct him in a sequel to "The Hustler," it was an offer Scorsese couldn't refuse. "The Color of Money" came at just the right time for Scorsese. "The King of Comedy" (1983) and "After Hours" (1985) hadn't exactly set the box office on fire. But Bright Lights Film Journal reported that "The Color of Money" grossed five times more than "After Hours" and earned Newman his best actor Oscar.

There seemed to be a consensus for years that "The Color of Money" was an inferior film to "The Hustler" and that it was a direct-by-numbers project for Scorsese. But it has gone through something of a re-evaluation in recent times, and Scorsese's delight to be working with a bona fide Hollywood star is evident throughout. FlavorWire reported that in his book "Martin Scorsese: A Journey," Scorsese explained, "A movie star is a person I saw when I was 10 or 11 on a big screen. With De Niro and the other guys, it was a different thing. We were friends. We kind of grew together creatively. But with Paul, I would go in and I'd see a thousand different movies in his face, images I had seen on the big screen when I was 12 years old. It makes an impression."

Scorsese does the voice-over in the film's opening scene

The opening scene to "The Color of Money" lets the viewer know they're entering a world of dimly lit rooms, whispers in the shadows, and steely-eyed hustlers who'll study your every move. There's a lone voice whistling in a friendly but strangely menacing manner, then a cut to a cigarette smoking away in the ashtray and to the pool chalk waiting to sharpen the point on some shark's cue. And then we have the evocative New York accent of Martin Scorsese telling us, "Nine-ball is rotation pool. The balls are pocketed in numbered order. The only ball that means anything, that wins it, is the nine. Now, the player can shoot eight trick shots in a row, blow the nine, and lose. On the other hand, the player can get the nine in on the break, if the balls spread right, and win. Which is to say, that luck plays a part in nine-ball. But for some players, luck itself is an art."

It sounds like the gospel according to Saint Grifter, and it's a sound introduction to a world where fortunes are made and reputations lost in nine-ball pool. It is also a stunningly effective trick that enables Scorsese to fill in the viewer who has no knowledge of pool on everything they need to know about the game. By clearing up the technical aspects from the get-go, Scorsese can plunge straight into the heart of the action. As Film School Rejects pointed out, Scorsese is something of a maestro in using dynamic and integral voice-overs to enhance his films. From Ray Liotta's "As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster" in "Goodfellas" to Leonardo DiCaprio's engaging narration in "The Wolf of Wall Street," Scorsese has turned the humble voice-over into high art.

Tom Cruise learned his own trick shots for the movie

Flashy trick shots are an essential part of any self-respecting pool hustler's arsenal. Bewitching opponent and spectator alike with a little razzle-dazzle is a great way of rattling nerves and getting people to take their eyes off the ball and the long game. Vincent Lauria is the sort of flamboyant pool player born to perform trick shots. He dances around the table doing Samurai-like moves with his cue and occasionally bursts into high-pitched screams. It's entertaining stuff, but you need to be able to walk the walk at the table if you're going to act the showman. Ever the hands-on actor, Cruise learned to perform all except one of the trick shots for "The Color of Money," via UPI. Scorsese believes Cruise could have mastered a shot that involved the cue ball jumping over others, but it would have delayed filming. Pro pool player Michael Sigel was called in to deliver the goods.

In an interview with Russell Harty for Film 87, Paul Newman explained that Cruise was a natural at playing pool. "Cruise was fantastic," Newman said, "never had a pool cue in his hands and he was as good, if not better than I was, in five weeks." Waltzing around a pool hall with Fast Eddie's legendary Balabushka in his hand, Vincent is asked what's in the case he's carrying. With a toothy grin on his face, he delightedly answers, "Doom!" When playing such a character, it's only right to learn a few trick shots of your own to back up the brag.

Scorsese revealed Tom Cruise was very respectful on set

Tom Cruise was nowhere near the worldwide star he was today when he appeared in "The Color of Money." But with "Taps," "Risky Business," and "Top Gun" under his belt, the kid was going places. Yet keen to learn at the knee of masters of their trade such as Paul Newman and Martin Scorsese, and not one to take his position in life for granted, Cruise kept any blossoming star ego in check on the set of "The Color of Money." During an interview with Midday, Scorsese explained that Cruise was "extremely enthusiastic and extremely respectful. In fact, he called Paul Mr. Newman, and me Mr. Scorsese for a few weeks, and we had to kind of rough him up to stop that."

Scorsese added, "You have to remember that when we cast Tom he was very big off 'Risky Business,' but 'Top Gun' had not opened yet. We just cast him because we thought it was the right way to go." Scorsese also added that there's no point getting star actors on board if you're going to "do a movie about a man starring at a wall watching paint dry for an hour. No matter how existential or philosophical that may be. If you're going to use Paul and you're going to use Tom, do something that's exciting and entertaining."

Scorsese viewed The Color of Money as a steppingstone to The Last Temptation of Christ

Although he began the decade on a high with the release of his masterpiece "Raging Bull," the 1980s soon became something of an endurance test for Martin Scorsese. The Ringer reported that toward the end of 1983, the director was dealt a double whammy. "The King of Comedy" had flopped like a dead fish at the box office, and, worse still, his long-cherished pet project, "The Last Temptation of Christ," had been put on ice by the studio, which felt the cinema-going public wasn't ready for Scorsese's version of the Gospels. By the mid-1980s, Scorsese was stranded in a film industry that appeared to value special effects and franchises over innovative mavericks. In Scorsese's words, "The industry had changed, and the day of the personal film was gone."

Keen to prove he still had what it took to wow audiences, and to persuade studios that a film adaptation of Nikos Kazantzakis' novel "The Last Temptation of Christ" was still viable, Scorsese began to throw himself into projects that audiences wouldn't normally associate with him, such as the video for Michael Jackson's "Bad." Although "After Hours" was not a hit, "The Color of Money" made $50 million in the U.S. and was financially Scorsese's finest hour up to that point. Flush with success, Scorsese engaged the services of a new agent, Michael Ovitz. Scorsese told The New York Times that Ovitz said, "What is it you want to get done? What is the film you really want to get made?" To which the director replied, "'The Last Temptation of Christ.'" Shortly, Universal gave Scorsese his wish.

Iggy Pop and a young Forest Whitaker make cameos

Although more renowned as a golfer (and a rocker) than as a pool player, Iggy Pop makes a brief cameo in "The Color of Money" as some guy in a bar whom Vince beats on his way to the big money in Atlantic City. Far Out reported that it's a bang-in-a-bottle kind of cameo, and Iggy doesn't have any dialogue. Yet what the "street walking cheetah" and "runaway son of the nuclear A-bomb" does have is presence — the sort of face that makes for a memorable barfly, particularly when Vince adds insult to injury and drinks his shot after taking his money. Pop is listed in the credits as "Skinny player on road."

A young Forest Whitaker, on the other hand, does have a little dialogue during his brief cameo and he uses it to disarming effect as the young hustler who shakes down Fast Eddie Felson. All innocent-eyed and smiling with an easygoing manner, Whitaker plays Amos, who draws Felson in with a basic but convincing con about being a hapless dude who participates in medical experiments for money. He lets Felson beat him, and then he's offered a double-or-nothing rerun. Amos decides to up his game and teach Fast Eddie just how slow he's become. Amos pretends he cannot believes how well he is playing and keeps apologizing for beating him. Finally, a devastated and disbelieving Felson asks, "Are you a hustler, Amos?" To which he replies, "You wanna quit?" Felson takes the bait and continues to lose big time. It's a defining point in the film — and newcomer Whitaker easily holds his own with a screen legend.

The Color of Money's release led to a surge in pool playing

Mark Twain once wrote, "Pool playing is better than any doctor's medicine" (via Quedos). The "Huckleberry Finn" author was in esteemed company when it came to his appreciation of the game's poetry. U.S. presidents George Washington, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Ulysses S. Grant, and Theodore Roosevelt found sanctuary in pool. Since its origins in the guise of billiards in the 14th century, the game has dipped in and out of popularity. In 18th-century England, pool was banned from pubs because hustling had become such a social problem. Its image for a long time was associated with those who live while governed by the flip of a coin and come from the wrong side of the tracks.

Movies such as "The Music Man," "The Hustler," and "The Color of Money" played up to this stereotype, and, truth be told, it didn't have a detrimental effect on pool's universal appeal. Following the release of "The Hustler" in 1961, everyone and their dog wanted to pick up a cue. Pool rooms appeared to open up overnight in the U.S. before the game's popularity took a nosedive in the 1970s. In 1986, "The Color of Money" introduced an unsuspecting generation to the wonders of the sport. North Hollywood Billiards Club owner Terry Moldenhauer told The Los Angeles Times upon the film's release, "The movie is a shot in the arms. Sales of cue sticks are up 25%. Pool table sales have increased. We're seeing an impact from 'The Color of Money' because kids need an idol to identify with and relate to. Tom Cruise could well be that person."

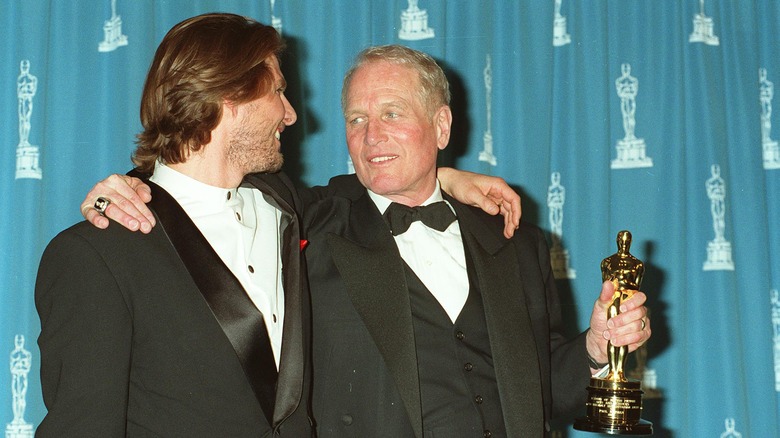

Paul Newman's Oscar win saw him join an exclusive club

Before "The Color of Money," Paul Newman had carved out a spellbinding career in films like "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof," "The Hustler," "Hud," "Cool Hand Luke," "Absence of Malice," and "The Verdict." He was nominated for an Academy Award for best actor in a leading role for all six of those films. Still, it wasn't until "The Color of Money" that he was recognized with an Oscar in competition (a year after winning a career-spanning honorary Oscar). The win also placed Newman in an exclusive club of husband-and-wife teams who had won Academy Awards. Us Weekly reported that, alongside the likes of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, Judy Garland and Vincente Minnelli, and more recently Michael Douglas and Catherine Zeta-Jones, Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward became a special kind of Hollywood power couple.

When asked by Film 87 host Russell Harty if he thought he'd win an Oscar for "The Color of Money," Newman he hadn't given it much thought, adding that the prestigious trophy had eluded him for a long time. "It's like chasing a beautiful woman for 80 years," he said, "and then it's 'Well, here I am.' And you say, 'So ... now what?'" Joanne Woodward won her Oscar in 1958 for "The Three Faces of Eve." Newman revealed that a win "would create some kind of balance in the house" before explaining, "Every time I get into an argument with Joanne about cooking or laundering shirts, she just shakes her Oscar at me and I'm dead in the water. So it would be kind of the great equalizer after 30 years."

Paul Newman fussed nonstop over Richard Price's script

In an interview with "Film 87" host Russell Harty, Paul Newman explained, "It's very dry out there. I know I'd like to do at least two films a year and now it getting lucky if I do a film every two years." He added, "There are no good scripts out there" — before clarifying that in the 13 years since he and Robert Redford had made "The Sting" they had not found another script they felt would be good enough for them to act in together. Newman said, "It's not out of a lack of desire but simply lack of material." Obviously, when an actor has that sort of view on scriptwriters they're potentially going to be a thorn in the side for whatever poor person eventually writes their lines. Such was the case with Newman and "The Color of Money" wordsmith Richard Price.

The New York Times reported that Martin Scorsese, Newman, and Price had numerous meetings in restaurants and offices to discuss every angle and direction of the script. "Everybody had his say and everything was out in the open," Newman recalled. "The great thing was that ideas just came up and blossomed. And it didn't matter who owned them." Price, who was brought in to adapt Walter Tevis' novel, had a different take. "We not only went over every word," he said, "we went over every punctuation mark." Price added how he would often hear Newman say, "'Guys, I think we're missing an opportunity here,'" and sigh to himself, "'Oh, no, here we go again.'" Price did add the caveat that Newman was rarely wrong with his input, but he also remembered thinking in the heat of the moment, "If I hear 'we're missing an opportunity' one more time, you're going to be missing a writer."

Scorsese wanted The Color of Money to be a stand-alone movie

When filming began on "The Color of Money," many industry insiders were surprised to learn that such a fiercely independent filmmaker as Martin Scorsese was willing to not only film a sequel but a sequel to a movie in which he had no hand. Although the director told The New York Times, "My tastes don't run to shooting sequels," he confessed to being a big fan of "The Hustler" and Paul Newman, so when he was asked by the man who played Fast Eddie Felson to direct a new vehicle featuring the iconic pool player, he was all ears. Determined to shoot a movie that could be enjoyed with or without seeing "The Hustler," Scorsese didn't want to do a literal sequel "based on at least some familiarity with the original." So he suggested to Newman they wipe the slate clean and develop a story different from that of the book.

"I don't know anything about pool," Scorsese explained. "I don't like what's on the table, but around the table, the intrigue, the manipulations." Yet for screenwriter Richard Price, a working knowledge of "The Hustler" added another layer of poignancy to "The Color of Money." The scriptwriter explained that Felson had turned into the "thing he hated most: the George C. Scott character in the original. He had become a stakehorse, a man who backs young pool players." Felson had become a man who had lost the one thing that made him great. "The Color of Money" is all about how he reclaims it.

Roger Ebert believes Martin Scorsese's heart wasn't in The Color of Money

Film critic Roger Ebert described Martin Scorsese as "the most exciting American director now working" in his review of "The Color of Money." But the rest of Ebert's review was scathing — he believed that Scorsese had sold himself short, and out, with the movie. He wrote that unlike other Scorsese films it lacked electricity, tension, and punch. Ebert admitted that if "The Color of Money" had been made by another director he wouldn't have had such high hopes or felt so let down. Ebert's opinion was that the trouble began when Scorsese decided to commit himself to the sort of mainstream project that was simply the wrong fit for his maverick spirit.

Ebert wrote, "I believe he has the stubborn soul of an artist, and cannot put his heart where his heart will not go. And his heart, I believe, inclines towards creating new and completely personal stories about characters who have come to life in his imagination — not in finishing someone else's story, which began 25 years ago." You can't please all the people all of the time, and as proved by Newman's Oscar, its box office success, and the fact it's still being discussed nearly 40 years later, "The Color of Money" continues to talk the talk and walk the walk.