Your Favorite Yellowstone Character Is Officially The Villain Of The Story

Of all the many melodramatic elements that drive the western powerhouse that is Taylor Sheridan's "Yellowstone," its Strong Female Character — Kelly Reilly's acerbic and developmentally arrested Beth Dutton — is the one the series relies on most. Part man-eater, part princess of the show's essential fairytale, and part perfect cowboy wife fantasy, she's both the daughter of Kevin Costner's John Dutton and the latest in a long linea of dangerous women in literary tradition. And like so many male-conjured Belladonnas, her one-dimensional strength and superficial agency are proving to be her downfall. As these stories tell us, this is what happens when you fly too close to the sun. Unlike Icarus, however, Beth's literary ancestors aren't punished for the sin of hubris, but for the sin of influencing — or having the same strong will, sexual prowess, and fearlessness as — their celebrated male counterparts.

If the historical and sociological events and ideologies that birthed her character are complex, Beth's motivations are less so. (For example, it took centuries for Eve to transform from the serpent's innocent victim into, if not the serpent itself, a lustful temptress in enthusiastic cahoots with it, per Bettany Hughes' exploration in "The Daughters of Eve.") Beth's mission is to serve her father, a mission she uses to justify taking her brother Jamie (Wes Bentley) out of the equation. For herself, she wants only the one thing that was taken from her. It's the driving force behind her hatred for Jamie and a desire that, most recently, saw her cross a line from which she may never return.

Beth threatened a baby, and that's a no-no

Both throughout history and in present-day politics, as low-hanging fruit propaganda goes, positing one's enemy as a danger to children — or literal baby killer — is right up there (or, down there) with accusing them of cannibalism or incest. And as a line that can't be crossed, it's as effective in literature, film, and television as it was/is for sowing real-world disgust and fear (e.g. the Satanic Panic). Once a character crosses that line, there's no going back.

Though the harming-children line has been used to great effect in both horror (hey, sometimes kids turn into zombies, and there's nothing one can do) and overtly irreverent works (e.g., "A Modest Proposal"), "Yellowstone" has no interest in irreverence, irony, or demon babies and zombie kids. It's a series that, as critic Liam Mathews writes, traffics in "cliche-bound genre traditionalism" (via TV Guide). And, traditionally speaking (though to be clear, this really should go without saying), actually murdering or threatening a helpless innocent is very bad, and not in a deliciously badass way, either.

Unfortunately, that's just what our delicious badass Beth did in Season 5, Episode 4 of "Yellowstone." When she learns that Jamie has a baby, she makes her plan abundantly clear. "I'm gonna take him from you," she says; "I'm going to rob you of fatherhood, Jamie. You don't deserve it, and he deserves better than you. Next time you see him, you can kiss him goodbye, because, he's as good as gone."

On its own, the threat appears to be against Jamie, and not against little Jamie Jr. But there's both context and foreshadowing to consider if we're to read its implied meaning, both as a potential plot point and as a repositioning of Beth's character.

Beth's previous promise and the root of her anger

In Season 2, Beth outlines her intentions for Jamie, saying "one day Jamie ... someone will love you. And you'll love somebody. And I can't wait to take that from you. Even if I have to kill it with my bare hands, I will take it from you." The identical verbiage hardly seems accidental. Beth wants to take from Jamie, as Jamie has taken from her, and if that involves killing someone, so be it. It's an extreme plan of attack, even for Beth, but it's important to remember what, in her eyes, Jamie is personally and solely responsible for taking from her.

After two years worth of withholding, Season 3 reveals all. When a tween-age Beth (Kylie Rogers) becomes pregnant with a tween-age Rip's (Kyle Red Silverstein) son, she asks her older brother Jamie, who is on the cusp of his freshman year of college, for help. For fear that taking her to the Planned Parenthood in Billings will result in everyone finding out about Beth's situation, Jamie takes her to a clinic on the Broken Rock Indian Reservation, where women seeking abortions are required to undergo forced sterilization. (Though the abhorrent, racist practice was most prevalent in the 1960s and '70s, the notion that the practice and its repercussions are no longer a reality of numerous populations — per JSTOR, Global News CA, and Lady Science — is false).

Though the administrator attempts to talk Jamie out of bringing Beth in (not because of the requirement, mind you, but rather because she's white), his fear of both his father and what people will think drives his decision, which he makes without consulting Beth.

Yellowstone's focus thus far hasn't helped Beth

Beth's lack of agency over her own body — and its resulting physical and psychological realities — could have lent a progressive undercurrent to a distinctly conservative series. As it stands, Beth's narrowly-focused hatred for Jamie and the violent, dramatic ways in which it manifests (from her attempt to push him into self-harm to her implied intentions for his child) are far more foregrounded than either the notion of agency in general or the ways in which that same lack of agency has impacted and continues to impact both Beth and the Broken Rock Indian Reservation.

The question the narrative pushes is not, "how and why did (and does) this happen," but, "is Beth's hatred for Jamie (considering his own lack of emotional maturity at the time) justified?" The latter is a fair question for the series to pose. However, its complete usurpation of the greater issue — combined with both the increasing sympathy with which "Yellowstone" handles Jamie, and Jamie's young age at the time of the event — suggest "Yellowstone" has already made up its mind about how we ought to feel about Beth's motivations. While her pain and trauma are warranted, her hatred for Jamie is less so. For a show bound by traditional genre arcs and archetypes, this approach feels almost inevitable, and it speaks, with fairly obvious clarity, to the narrative's remaining options.

Will Beth be reduced to a tired trope?

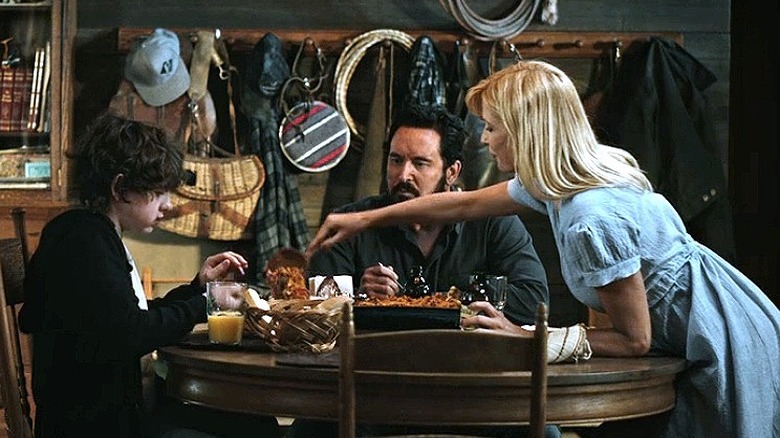

"Yellowstone" spends a good deal of time in Season 4 reminding us that, for all her lack of domestic prowess (which is, of course, balanced by her abundance of Perfect Wife sexual prowess), Beth just really wants to be the matriarch of a family. Never is her character more cottage-core chic than when she's dishing out questionable Hamburger Helper to her acquired child and strong, supportive, patient husband. But what could have added depth and a more nuanced depiction of strength to her character reveals itself, in Season 5, to have been a trap.

Beth's desire for a family doesn't give the viewer a different perspective on her, and it doesn't reveal more complex facets of her already family-above-all-else (except Jamie) personality. Instead, and like Medea before her, it drives her to unspeakable acts of violence. If Beth does rain her revenge down on Jamie in the form of harming his child — either physically, as previously promised, or by putting her desire for vengeance over the needs of a child — she'll officially become not just a villain, but yet another warning of the dangers of being an angry woman with a strong will — aka, the classic Madwoman.

In "Dissecting the Madwoman Trope," essayist and poet Yashica notes that contemporary works have made some headway. "Now, the women are not simply mad or angry but their rage is more nuanced and complex," she wrote of more recent spins on the device, later adding, "Their anger and agony are explored and the audience gets a chance to empathize with their characters instead of marking them off as lunatics."

Season 5 is certainly heading that direction

For all its traditionalism, "Yellowstone" has, to its credit, attempted to imbue Beth with nuance and complexity, as The Atlantic's Megan Garber explores in-depth. There are numerous instances in which we empathize with Beth — in no small part thanks to Kelly Reilly's performance — and the roots of her anger toward both Jamie and herself are repeatedly explored. However, we don't see it explored by Beth herself — "I am the rock therapists break themselves against," she says. Beth's arrested development means that despite her veneer of power and grit, she has no more agency over her mind or her actions than she had over her mother's death or her body as a teen. "The traumatized, without intervention, can become trapped in the moment of their injury," Garber wrote.

Unfortunately, the series itself is also trapped. Beth's storyline has become repetitive, but instead of her character (for instance) seeking treatment, or exhibiting any form of emotional growth, she's only grown more violent. Between cracking open a tourist's skull, beating Piper Perabo's Summer to a bloody pulp, and threatening Jamie's child (all events which occurred in episodes airing after Garber's analysis) Beth isn't simply trapped, nor is she simply digressing. She's escalating, and at the same time, the series is increasing its empathy for Jamie. Lest we forget, this is someone who murdered both a reporter and his own biological father).

Beth and Yellowstone's legacy are intertwined

If "Yellowstone" hopes to avoid turning Beth into the cliche madwoman it's for so long attempted to avoid, it cannot allow her to exact her revenge via a child, no matter her motivation. But will it?

One might argue that the show's penchant for romantic arcs and archetypes is the exact thing that will keep it from pushing Beth entirely past the point of no return. Forgiveness and redemption are some of the most traditional themes such a story can engage in, and it does seem far more likely that the series will see Beth ultimately overcome her anger and hatred than give in to them. The odds of her magically seeking out the therapy she so desperately needs are slim to none, but as the classic outcast, Jamie is ripe for redemption in the form of sacrifice. Meaning, he can't regain Beth's trust or forgiveness in life, but in sacrificing his own (likely, though not necessarily, literally) to prove his loyalty to the Duttons or to protect his son, he might at least earn some semblance of absolution.

For now, all that remains to be seen. All we can say for sure, in the wake of "Horses in Heaven" and "Watch 'Em Ride Away," is that the formerly line-toeing Beth has officially crossed one too many, and both her legacy — and the series' treatment of its central strong female character — rely on her finding her way back over.