Small Details You Missed In Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio

Of all the directors working today, there is probably no one who's style called out for stop-motion animation than Guillermo del Toro. Pairing with co-director Mark Gustafson, a veteran of claymation most famous for animation direction on "Fantastic Mr. Fox," del Toro brings his full vision to bear with his version of the classic story of Pinocchio. Ever since Carlo Collodi's original novel "The Adventures of Pinocchio" in 1883, the story of our favorite wooden puppet has been adapted dozens of times, most famously in hand-drawn animation by Disney in 1940 (and in live action by Disney earlier this year). But even beyond the need to distinguish it, it's telling that the new Netflix adaptation has the full title "Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio": It's the product of his very specific imagination.

Like his earlier works "The Devil's Backbone" and "Pan's Labyrinth," "Pinocchio" pits the magical optimism of childhood against the inescapable horror of history, but trades the Spanish Civil War for the backdrop of Mussolini's Italy before and during World War II. Del Toro's "Pinocchio" falls somewhere in between transporting fantasy and grim anti-war parable, splitting the difference evenly between the darker tone of the original story and the iconic whimsy of the Disney version. It's a complex, dense story that will reward repeat viewings narratively as well as visually — all the unmistakable product of Guillermo Del Toro's mind — as well as highlighting some blink-and-you'd-missed them details. Here are some of the small details in "Guillermo Del Toro's Pinocchio" you may have missed.

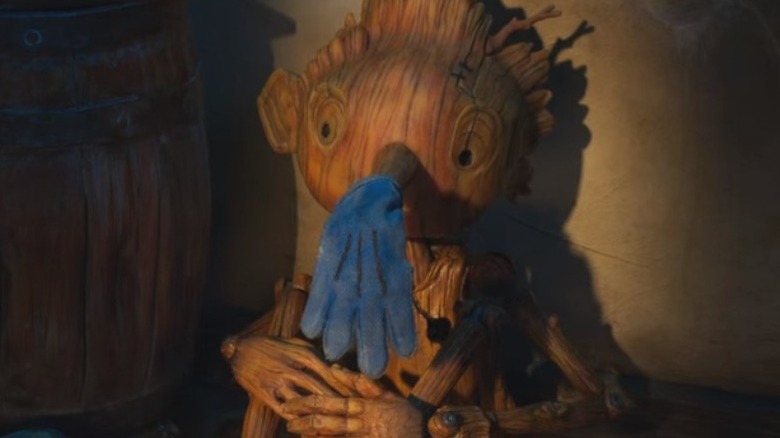

Pinocchio is unfinished

Although each of the "Pinocchio" puppets cost more than your car individually, the actual design of Pinocchio (voiced by Gregory Mann) by Gepetto (David Bradley) reflects the haphazard circumstances of his creation: Geppetto is intoxicated and in a place of deep grief while creating him, and he cuts a few corners. In contrast to the crucifix Gepetto fashions for the local church, as well as the much more ornate and painted figurines in his workshop, Pinocchio is all unfinished wood with visible knots and cracks and a branch sticking out of the back of his head. It's a miracle that he manages not to destroy the "home" of Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan MacGregor), right around Pinocchio's heart.

Although it's not exactly subtle — Gepetto even says he'll "finish him tomorrow" out loud — Pinocchio is brought so well to life for the rest of the movie that his raw character design fades to the background, especially since he's essentially immortal. But it's easy not to notice, for example, that Pinocchio only has one ear for the entirety of the movie. Unlike the picturesque, almost human-looking Pinocchio in the classic Disney version, del Toro's Pinocchio is an unvarnished, vulnerable image of the turbulent emotions of his creator.

The bomb is a reference to The Devil's Backbone

Guillermo del Toro loves to tell stories about childhood and war, specifically holding onto the magic of childhood amidst the unfolding of a historically significant conflict. "Pan's Labyrinth" and "The Devil's Backbone," two of Del Toro's best movies, are set during and after the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. "Pinocchio" stays in the tumultuous '30s and shifts the setting to Italy, contrasting Pinocchio's streak for disobedience against the rise of Mussolini's fascism. To keep this unofficial childhood/wartime trilogy connected, del Toro snuck in some references to the other two movies.

The stained glass in the local church has images of the Faun and the Pale Man from "Pan's Labyrinth," although they're kind of impossible to spot during the movie but visible in "Guillermo del Toro's Pinocchio: Handcarved Cinema," a documentary that's also available on Netflix. Easier to catch is the visual parallel to "The Devil's Backbone": The bomb that falls on the church is framed exactly the same way as the sequence in Del Toro's earlier film, and the bombs themselves look identical. Of course, the one in "The Devil's Backbone" is a dud that looms inertly over the proceedings of the whole story, and in "Pinocchio" the bomb goes off and brings poor Carlo's life to an abrupt and tragic end.

The stained glass of the church foreshadows the bomb

A detail that's clearly visible in the church — that is, before it's blown up by a plane just unloading its bombs carelessly to reduce yield — is a grim bit of foreshadowing. A stained glass window, which against the night sky appears to be an image of a dove (a common religious symbol of peace), becomes even more significant in the golden light of late evening. When Geppetto and Carlo are wrapping up work on the crucifix, the wings of the dove are a different shade of blue, and the image looks uncannily like the bomb that will soon fall and destroy the window altogether.

In a thoroughly unsubtle move, the dove-bomb is framed one shot directly above the doomed Carlo's head. It looms like Carlo's death does over the entire opening sequence. The montage of Geppetto and Carlo's happiness rivals the opening of "Up" — one of the best scenes in Pixar history – knowing that doom is imminent makes it all the harder to bear. Upon rewatch, even the church itself seems to know what's coming.

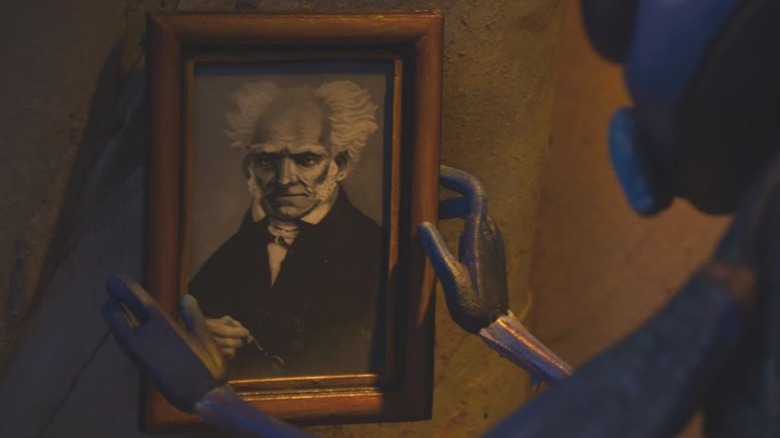

Sebastian has a tiny portrait of Arthur Schopenhauer

Sebastian J. Cricket, Pinocchio's eventual companion and guide, is the narrator of this version of the story and claims to be a well-traveled, intellectual writer. As proof, of a sort, when he's unpacking to move into Carlo's tree he puts up a teeny, cricket-sized portrait of what at a glance seems like it could be any historical famous writer that he looks up to — perhaps Charles Dickens or Carlo Collodi himself. But a second glance at the unmistakably wild crown of white hair reveals that it's none other than noted German philosopher Arther Schopenhauer.

Why Schopenhauer? Well, he was famous for what's known as "philosophical pessimism," a sort of bleak understanding of life that's right in tone with the overall darkness of "Pinocchio" and with the pratfall-laden antics of Sebastian himself. As the Professor David Woods wrote for Aeon, "Schopenhauer claims, if our world is ordered in any way, it is ordered to maximize pain and suffering." Sebastian has clearly made this part of his world view, as he exclaims overwrought things like, "Oh the pain! Life is such hideous pain!" when he gets repeatedly stepped on and squashed.

A small Disney reference

Disney's 1940 version of "Pinocchio" is so iconic that many people might not even be aware that it's based on an existing Italian novel. Like many of Disney's other properties, fans are so protective of the 1940 "Pinocchio" that they were quick to say how they really feel about the recent live-action version. Guillermo del Toro — perhaps to at least acknowledge that he's treading on some dangerous ground by making a wildly different version of the story — throws in one small reference to the iconic Disney version of the character when his Pinocchio is briefly stuffed in a closet by a terrified Geppetto.

After he crashes into the closet, Pinocchio has a glove stuck on his nose for a brief moment that resembles a blue version of the classic white gloves worn by Disney's Pinocchio, as well as Mickey Mouse and many other classic cartoon characters. It's a small gesture, one that's tellingly placed on Pinocchio's nose, his barometer for lying. Del Toro's Pinocchio, with his five ungloved and fully articulated fingers, won't become a real boy, won't get turned into a donkey, and won't even learn a lesson about lying over the course of this version of the story. The blue glove is a defiant statement that del Toro has a much different agenda than Disney's typical feel-good vibes.

The church is still not repaired, decades later

Like many countries after World War I, Italy's economy was struck by inflation, unemployment, and strikes. This instability led to fears of a revolution, and those fears were what allowed Benito Mussolini and the fascist party to rise to power on promises of restoring law and order. By the end of the 1920s, the worldwide Great Depression tanked the economy yet again. This general economic climate is reflected in the church's continual state of disrepair. It's easy to miss in the wide shot, but when Geppetto and Pinocchio are at last finishing the crucifix, large portions of the roof and walls are still missing.

Although Mussolini instituted major public works projects in Italy's major cities, rural towns like Geppetto's were unlikely to be major points of interest for the Fascist party, and the local townsfolk have clearly been unable to afford much in donations themselves. Like Geppetto, the church and the town still carry the deep wounds from the first World War in the run up to the second. The local priest (Burn Gorman) even takes Geppetto's carving of Pinocchio somewhat personally: He's offended that Geppetto's carved a "monstrosity" of a surrogate son puppet instead of finishing the crucifix for the poor, war-torn church building.

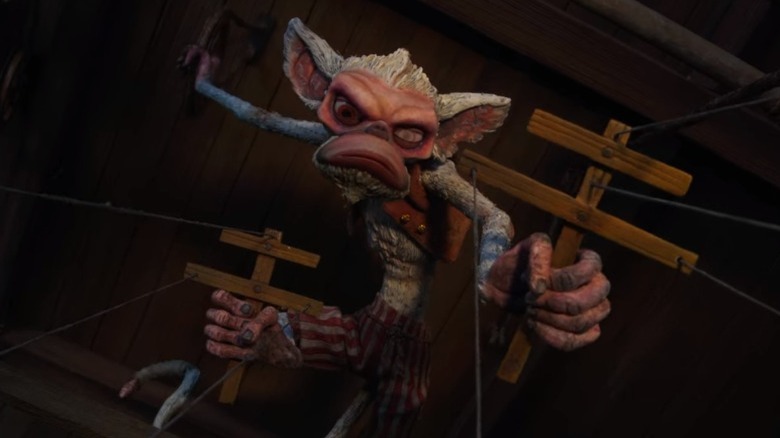

Volpe looks just like his fox sceptre

One of the best inventions for del Toro's "Pinocchio" is Count Volpe, a debonair fallen aristocrat that runs a carnival and tempts Pinocchio into a life of stardom. He's wonderfully voiced by the great Christoph Waltz, and deserves his own origin story as much as any Disney villain. In a delightful small touch, as he takes on the role that the Fox played in the original Collodi story, Count Volpe has wild red hair that look like pointy ears, as well as angular and foxlike mutton chops. His name, Volpe, is of course Italian for "fox" also.

If that weren't enough, as a finishing touch he bears a striking resemblance to the gold fox-head statue that's on the head of his own scepter. The scepter is no mere walking stick: Revealing hidden deviousness much like its owner it turns out to be a sword during a key confrontation later in the film.

The murals in town change with the times

The creep of fascism is steady during the course of "Pinocchio" — eventually Pinocchio will sing truth to power by basically calling Mussolini a "doo doo head" right to his face. But early on in the movie, the backdrop of the local town shows the way that fascism's reach extends to the quiet and rustic corners of life. A building during the Carlo and WWI years has a pleasant mural showing a woman with a basket of fruit and the phrase "Festa del Raccolto" or "Harvest Festival." Years later, during the fascist era, the same building is seen not only noticeable dingier and with boarded-up windows, but it also bears a mural of a grim-faced solder and the words "Credere, Obbevire, Combattere," or "Believe, Obey, Fight."

The true fascist nightmare fuel isn't just in marches and political fanfare; it's the erosion of differences among people, and it's in the replacement of regional traditions and color with party unity and national identity. The paintings on the walls become tests of loyalty, just like something as small as Pinocchio's refusal to attend school is taken for dissidence.

Spazzatura can speak fluently

Depending on how much you research the film ahead of time, on of the most surprising reveals in the credits of "Pinocchio" is that not only is Cate Blanchett a voice in the movie, but she voices Count Volpe's monkey companion Spazzatura. Although it apparently wasn't easy to find the right voice, she does a more than believable job as the beleaguered servant. But in two scenes that are easy to miss the implications of, she actually uses her voice when Spazzatura acts as a puppeteer for Volpe's non-magically-brought-to-life puppets, revealing the somewhat shocking fact that Spazzatura the monkey can speak flawless English.

For the most part, the rules of the magical realism of "Pinocchio" are never entirely clear. People are shocked to see a living puppet for the most part, but Sebastian the talking cricket is at points seemingly understood by humans like Geppetto without comment. But it seems like a talking monkey would be at least nearly as big of an attraction for Volpe as a living puppet? Unfortunately, Spazzatura only seems capable of articulated speech when puppeteering, although he can also throw his voice so expertly that Pinocchio seems to be fooled into believing the other puppets are also alive.

Death has pine cone scales on her tail

Tilda Swinton, a natural at playing supernatural characters like vampires and no stranger to dual roles, voices both the Wood Sprite that brings Pinocchio to life and the embodiment of Death that greets him in the strange, blue limbo that he goes to each time that he dies. Like her sister, Death has brilliantly glowing blues eyes, and a combination of many different animal features. But her tail has a detail that connects her to an important motif throughout "Pinocchio": It's scaled in a way that resembles the scales of a pinecone.

"Pinocchio" begins and ends with an image of a pinecone, and in between they symbolically represent the entire cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Carlo is killed attempting to retrieve his "perfect pinecone," the one that "still has all of its scales," and that same pinecone later grows into the tree that will become Pinocchio's body (as well as Sebastian's home and final resting place). It's easy to miss amidst all of the hourglasses and emotional resonance of Pinocchio's death scenes, but Death's tail connects her directly to the movie's elegant pinecone imagery.

Geppetto saves Pinocchio's goodbye note

After tumult and misadventure, all ends well for Pinocchio, Geppetto, Spazzatura and Sebastian, as they wile away the rest of their lives (Pinocchio excepted) in Geppetto's small home. If you look closely, you can spot a small memento from the course of the movie, one that it's heartwarming to see Geppetto saved. On the mantelpiece above the fire, the "goodbye note" that Pinocchio left behind when he took off to join Volpe's carnival is visible, framed and well preserved after many years.

The "note" is, of course, just the drawing of a smiling sun that also stands in for Pinocchio's signature. During the montage, Pinocchio is also seen reading to Geppetto from a book of children's stories. Hopefully, he's long since gotten over his distaste for attending school and learned to write properly as well. In any case, it's nice to see the goodbye framed as a testament to a happy resolution, even though it did lead directly to Geppetto being swallowed by a dogfish.

Sebastian's matchbox has one of the skeleton rabbits on it

In a clear tie-in to the strange afterlife realm populated by Death and her team of working-class skeleton rabbits, the matchbox that serves as Sebastian's coffin and final resting place has a drawing of a very similar rabbit on the cover ("Fiammiferi" is just Italian for "matches"). The rabbits are one of the most fun and intriguing parts of "Pinocchio" because they apparently earn wages and punch a clock in the strange limbo realm and occupy themselves between shifts with an endless game of poker — the "queen" in their deck of cards is also depicted as a blue rabbit.

Over the end credits, Sebastian is revealed to not just be in limbo with the rabbits himself but to have even earned a coveted invitation to their poker game. Limbo apparently doesn't worry about relative sizes. Like Pinocchio, he stands the same height as the rabbits, even though Sebastian himself is much smaller than Pinocchio. But his choice of "coffin" has endeared himself enough to buy some time before facing Death, and he even gets a chance to finally sing the song he's tried to sing at two different points in "Pinocchio" without being interrupted.