Pixar Movie Details Only Adults Notice

Since the moment Toy Story debuted in 1995, Pixar has been a household name among adults as well as their animation-loving offspring. For better or worse, they ushered in the age of computer animation with a string of hit movies that resonated with critics and audiences. The key to their success has always been their goal of entertaining all ages, telling stories aimed just as squarely at adults and teens as they are at kids.

Some moments aren't meant for children at all. For instance, The Incredibles strings together its colorful superhero action with very real marriage drama and stark confrontations with mortality. The sequel will surely continue this method when it flies into theaters this June.

With decades having passed since their debut feature, Pixar's characters are now childhood favorites for whole new generations. The kids who were dazzled by Toy Story have kids of their own, and are picking up on the mature themes, sophisticated references, and trade secrets that make these movies timeless. If you're one of those adults, you might be surprised by some of these things you probably didn't notice before.

Coco had a controversial road to success

Pixar's latest effort has been one of their greatest successes, raking in record-setting box office and near-universal praise. In fact, it earned the studio their ninth Best Animated Feature Oscar. Most importantly, it's been embraced by the people of Mexico, who made it the most successful film in the country's history.

But Coco had to earn that love first. The film gained notoriety early in its production, when Disney (Pixar's parent company since 2006) attempted to file a trademark on the phrase "Dia de Los Muertos" in 2013. As Affinity Magazine documents, there was a public outcry against the idea of such a major American corporation trying to claim ownership of a Mexican holiday.

Mexican-American artist Lalo Alcaraz gained particular attention with editorial cartoon titled "Muerto Mouse." Disney/Pixar's first two steps to correct their major misstep were to withdraw the trademark filing and to hire Alcaraz as a consultant. As reported by Latinx Spaces , more controversy arose when Twitter users pointed out the similarities between Coco's trailer and The Book of Life, another film about Dia de Los Muertos produced by Fox in 2014. (Book's director, Jorge R. Gutierrez, graciously wished Coco success.)

With Alcarez's guidance, co-directors Adrian Molina and Lee Unkrich led the Coco team to victory. They populated the film with an all-Latinx voice cast (the highest-budgeted film ever to do so) and held the world premiere in Mexico, factors that certainly contributed to its acceptance by the culture it depicts. Only adults are likely to take note of Coco's bumpy road to success, however; kids should simply find an engaging story that celebrates underrepresented people.

A113 is everywhere

The California Institute of the Arts was founded in 1961 by a group of artists that happened to include Walt Disney. Its animation department would eventually become legendary, giving aspiring filmmakers a place to learn from the original masters of the art form. Its graduates have shaped the face of the animation industry, and they all had to pass through room A113.

In 2014, Vanity Fair profiled the CalArts graduates of the 1970s, a group that would go on to be largely responsible for the success of Cartoon Network, the fabled Disney Renaissance, and, of course, the phenomenon of Pixar. Many of them retained vivid memories of character animation classes in A113. "It had no windows and no door," illustrator Nancy Beiman recalled, "and you had buzzing fluorescent lights, and it was dead white inside."

That's why sharp-eyed enthusiasts have caught glimpses of this fabled code number scattered all over Pixar's films. Sometimes it's as subtle as a plaque in the background of Up. Sometimes it's as prominent as the pivotal executive order in Wall-E. And it's not just Pixar — CalArts graduates have snuck A113s into The Simpsons, American Dad, and even The Avengers.

A Bug's Life is a retelling of Seven Samurai

Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai has been a towering influence on cinema since its release in 1954. The most significant work it inspired is probably The Magnificent Seven, John Sturges' 1960 westernization of the story, which itself spawned three sequels, a TV series, and a remake. Less recognized is that Pixar has their very own version of the story.

Kurosawa's film tells the story of a village that is doomed to be raided by bandits after harvest season. The village's farmers set out in search of samurai who will protect them in exchange for food. They assemble a group of ronin who are mostly either past their prime or inexperienced, and the ragtag team trains the villagers to defend themselves.

Pixar's second feature film, 1998's A Bug's Life, introduces a colony of ants whose grain harvest is being targeted by a roving band of grasshoppers. Outcast ant Flik seeks help from tough bugs, and finds a troupe of disgraced circus performers. Flik mistakes the clowns for warriors after half-witnessing a bar fight, and the promise of food is enough for them to play along with the misunderstanding.

It's certainly not as much of a one-to-one remake as Magnificent Seven. Pixar cites the Aesop Fable "The Ant and the Grasshopper" as the genesis of A Bug's Life. But the similarities in concept are undeniable, as highlighted by a comparison at Decider.

Inside Out tackles depression

Pixar has always blown audiences away with their ability to imbue characters with feeling. Their casts of monsters, fish, toys, and even cars have captured the hearts of millions with their relatability. The studio took this devotion to emotion to a whole new level with Inside Out, a story about the feelings of, well, feelings.

What only adults realize is that Inside Out is more than just a roller coaster ride through the human mind. Many grown-up viewers see the misadventures of Joy and Sadness as an allegory for depression, as central kid character Riley struggles to accept her own unhappiness. Newsweek profiled a group of six child psychiatrists who viewed the film through this lens when it was released in 2015.

Dr. Fadi Haddad praised Inside Out, stating, "I've never seen a movie like this that talks about the brain and the emotional part of the brain in kids." Haddad specifically appreciated Pixar's efforts to show the value of sadness. Dr. Judith F. Joseph agreed, describing Riley's story as "pretty accurate in terms of what you see with depressed pre-teens." Though they stressed that Inside Out "shouldn't replace neuro-anatomy in medical school," some of these professionals even intended to use the film to spark discussions in their sessions.

They love The Shining

Many modern animated films are rife with pop culture references. From Shrek's abundant spoofs to The Lego Movie's toy box full of Warner Bros. characters, filmmakers love to hook kids by showing them things they'll recognize. Pixar has a fondness for one movie in particular, but only adults will notice. For one thing, the allusions tend to be pretty subtle. For another, it's something the pre-teen set really shouldn't be watching.

References to Stanley Kubrick's The Shining have been littered throughout Pixar's feature films from the very beginning. Some are fairly prominent, like the Overlook Hotel's distinctive carpet lining the halls of Sid's house in Toy Story. Others fall more into the "blink-and-you'll-miss-it" category, like repeated uses of the number 237 or the hotel office PA system appearing in Toy Story 3.

Though he doesn't take credit for every Overlook Easter egg, Lee Unkrich is undoubtedly Pixar's biggest Shining devotee. One of the studio's core filmmakers, Unkrich has directed or co-directed many of their hugest hits, including Coco, Finding Nemo, Monsters Inc., and Toy Story 2 and 3. When he's not busy with all that, he maintains a blog, TheOverlookHotel.com, which he started primarily as a backup for the wealth of Shining ephemera on his computer.

In an interview with Empire, Unkrich revealed the depth of his adoration for this horror masterpiece. Beyond in-joke references, he cites the filmmaking lessons he learned from studying Kubrick and how he brings them to the medium of animation. He even hopes to compile a book on the making of The Shining, if he ever gets enough time between Pixar projects.

Monsters University has a lesson about failure

A prequel is always a tricky proposition. When the audience already knows about your characters' futures, it robs your story of a certain amount of tension. That makes the ending of Monsters University particularly impressive, as it not only provides a surprise twist, but presents kids with a pretty subversive message.

The film travels back to the school days of Monsters, Inc. heroes Mike and Sulley. Beginning as rivals, the plot runs them through the various tropes of classic college comedies like Animal House. By the story's end, however, the pressure to excel has left them unsure of the career paths that once seemed so certain. They end up expelled, but the duo, now bonded in friendship, can be seen working their way up the company ladder in a cheerful end credits montage.

A column at College for the Win spells out why this ending is unique among kids' movies, explaining, "Too often is college seen as the only option, and the message is that if you don't go to college, you are a loser and will never succeed." Director Dan Scanlon confirmed this goal in a Huffington Post interview, stating, "We felt that was something we had never seen in movies, especially family movies — yet it was something that had happened to so many of us, where we had one path and then veered into another direction."

The Incredibles reflects the comics industry

The Incredibles takes place in a timeline not quite our own, a retro-future world that takes style cues from the real 1960s. Bob Parr, a.k.a. Mr. Incredible, fondly remembers a golden age of freedom, not just from the pressures of family life, but from restrictions placed on superheroes by the government. Frustrated by structurally-imposed mediocrity, Mr. Incredible begins to carry out clandestine missions in secret. Adults who know their comic book history might notice a parallel between this story and the real-world superhero art form.

In 1954, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent, a book that drew connections between juvenile delinquency and the rise of comic books. In response, publishers formed the Comics Code Authority, a self-policing body much like the film industry's MPAA. By the '70s, a rebellion to the Code was brewing, with the "Underground Comix" movement and Marvel stories that tacked drug issues by forgoing the Code seal. Creators were determined to follow their own moral compasses, just like the Incredible family.

Writer/director Brad Bird has stated that he didn't have any specific comic books in mind while crafting The Incredibles, but the parallels are rewarding for superhero enthusiasts. Incidentally, the Comics Code was at last formally abandoned after the turn of the new millennium, just as The Incredibles burst into theaters.

Ratatouille parallels their relationship with Disney

To most of the public, Pixar is synonymous wih Disney, who have distributed all of their feature films. Pixar's characters have long been fixtures at the Disney parks, and their stories sit comfortably on the shelf alongside Walt's masterpieces. But it wasn't until 2006 that the two companies truly became one, and many people don't know that it very nearly didn't happen. When the original contract between Disney and Pixar expired with the release of Cars, its renewal was far from certain.

Disney, naturally, wanted more Pixar content to add to their library. Pixar was faced with a choice between creative autonomy and financial stability, and concerned about control of the characters they had created during the partnership. This conflict happened to coincide with a particularly tumultuous time for the Disney Company. Tor's Mari Ness has detailed these negotiations and their connection to the film that Pixar had in production at the time, Ratatouille.

Fans have speculated that there's an autobiographical element to Ratatouille that stands as a metaphor for Pixar's relationship with Disney. In this theory, Pixar is Remy, inspired by the works of Auguste Gusteau, a Walt Disney analogue. Gusteau's iconic restaurant, representing the Disney Company, has stagnated in the years since its founder's death, staying in business by marketing mass-produced frozen entrees, a condemnation of Disney's habit of churning out direct-to-video sequels in the '90s.

The filmmakers behind Ratatouille have never commented on this reading, in which Pixar's need for a trusted public face to present their ideas is reflected in Remy teaming up with chef-in-training Linguine. Audiences not invested in studio politics will just see what really matters: a story about artistic expression and the balance between business and passion.

Wall-E is their most political film

In an election year, it can be easy to read political messages into any piece of entertainment, regardless of how intentional they may be. 2008 was a particularly contentious time, as Barack Obama and John McCain campaigned for the presidency and the era of George W. Bush drew to a close. That summer saw the arrival of Wall-E, Pixar's most directly satirical story to date.

It may seem hypocritical for a film distributed by the Walt Disney Company to condemn capitalism, but that's an undeniable part of Wall-E's message. In the future, the Earth has been made uninhabitable by the literal mountains of trash consumers have left piled across the landscape. The Buy N Large corporation, a shopping chain so ubiquitous its CEO functions as the American president, has led humanity into space, where people are surrounded by screens that inundate them with advertisements.

Not only does Wall-E raise concerns about climate change, its vision of the future of shopping makes some incisive observations only adults will notice about the age of in-app purchases that was just beginning to dawn. The target of the film's skewering becomes even more pointed when the Buy N Large CEO declares the company's intention to "stay the course," a controversial catchphrase of the Bush administration.

New York Times columnist Frank Rich highlights these themes in an Independence Day 2008 op-ed titled "Wall-E for President." Highlighting the ways in which the movie reflected the concerns of the campaign, Rich observes that its message was not lost on children, even if they didn't recognize its real-world allegories. "What they applauded was not some banal cartoonish triumph of good over evil," he writes, "but a gentle, if unmistakable, summons to remake the world before time runs out."

Their shorts are experiments

Pixar has sparked a return to the long-lost tradition of running short cartoons before feature films. Ever since A Bug's Life, they've warmed up the crowd with a few minutes of animation, usually dialogue-free, playing with such diverse topics as alien abduction, magic shows, and lovesick umbrellas. The shorts have been just about as crowd-pleasing as the features, earning Academy Award nominations and receiving their own art books and home video collections.

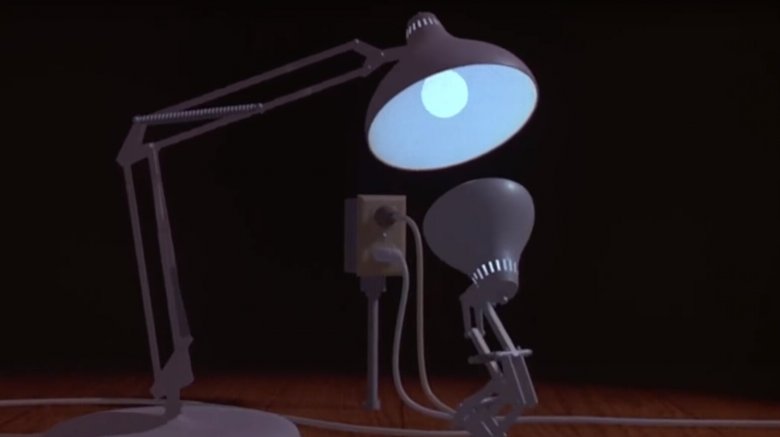

But Pixar doesn't just make these micro movies for their own sake. Look beneath the surface of their entertainment value, and it becomes clear that the short films are development labs for new techniques and training grounds for up-and-coming filmmakers. This tradition dates back to the very beginnings of the studio, when director Alvy Ray Smith debuted "André & Wally B." in 1984 with the goal of proving that basic character animation was within the realm of computer generated imagery.

Pixar continued to look to its experimental shorts for guidance as they rose to prominence. 1988's "Tin Toy" planted the seeds of what would become Toy Story. "The Blue Umbrella" broke new ground in the art of realistic environments in 2013. Of course, the most iconic Pixar short will always be 1986's "Luxo Jr."with its little lamp that would become their logo. A 2011 Slashfilm article illustrates the many motivations and processes behind the shorts via an in-depth look at the production of "La Luna." In 2017, Pixar announced the formation of a new "Experimental Shorts Division," the first results of which will be seen when "Smash and Grab" debuts before The Incredibles 2.