The Ending Of The Witcher: Blood Origin Explained

With the release of "The Witcher: Blood Origin," Netflix has revealed even more of the universe surrounding the titular mutated monster-hunters, and it's as dark, bloody, brutal, and paradoxically full of song as the core series, "The Witcher." No, it doesn't feature any of Henry Cavill's Geralt (though neither will the main series, soon enough), but it does assemble its own cast of misfits, monsters, and otherwise mistreated mortals. Set roughly 1,200 years before the events of "The Witcher" and "The Witcher: Nightmare of the Wolf," the new miniseries takes fans back to the early days of the Continent, before the Conjunction of the Spheres littered it with a menagerie of mythical creatures, and therefore before the need for Witchers.

The Continent is an altogether different place in "The Witcher: Blood Origin," though by the end of the series, a few of its most notable features start to rear their ugly heads — and in the classic style of Andrzej Sapkowski and his world, the ugliness is matched with an equivalent beauty. A lot happens in the series to transform the young setting into something akin to the world of Geralt and Ciri's (Freya Allan) adventures, enough that it's worth exploring more deeply. To that end, here is the ending of "The Witcher: Blood Origin" explained.

The rise and fall of Elvendom

In the time of "The Witcher," the Continent is a hodgepodge of social, political, and religious groups, seemingly subject to an endless cycle of war and racial conflict. Much of that strife comes as a result of human machinations, as the many human nations of the Continent are prone to infighting just as often as they are to prejudice against Elves, Dwarves, and the like. One of the setting's most enduring and poignant features is the abundance of Elven ruins and artifacts across the land, over which humanity builds their empires and attempts to recreate old Elvish magics. Yet in "The Witcher: Blood Origin," humanity has yet to arrive on the Continent, and in its place, the Elven empires prove themselves every bit as bloodthirsty as their eventual human successors.

The series begins with three major Elven kingdoms uniting under one banner, with Xin'trea (later known as Cintra) as its capital city. The unification is no feat of diplomacy, but rather the act of a few scheming, power-mad individuals — namely, Balor (Lenny Henry) and Eredin (Jacob Collins-Levy) — and accordingly, the new, unified empire is built on a shaky foundation. This period is known in canon as a golden age in Elven history, and yet even then is a violent, tenuous time. By the series' end, the death of an empress, the shattering of dimensional barriers, and a peasant uprising all bring the so-called golden age to an ugly end.

Eredin and the Wild Hunt

Though they've yet to properly arrive in "The Witcher" to hound Ciri and plague Geralt's dreams, the Wild Hunt is one of the greatest threats in the Witcher canon and is likely to end up as the series' overarching villains. In the Sapkowski novels, video games, and other media, the Wild Hunt is the primary group (alongside the Nilfgaardian Empire) responsible for Ciri's constant pursuit and nomadic lifestyle. They want the unique power afforded Ciri by her Elder Blood, a power that is prophesied to either end the world or save it, and all of their efforts begin in the final moments of "The Witcher: Blood Origin."

When Balor betrays Eredin and casts him out into an unknown dimension (ironically cursing the eventual frost mage to burn for all eternity), the Elf seems doomed to a slow death on a dead, alien world. But it's precisely that exile that causes Eredin, alongside his band of loyal soldiers, to begin transforming into the fearsome Wild Hunt. Eredin's singular determination allows him to survive exile, discover the secrets to interdimensional travel, and return to the Continent (as well as other worlds) as the King of the Wild Hunt. Using advanced magic found only on other worlds, Eredin and his band evolve into something more than simple raiders — wielding frost magic and commanding elemental beasts, they become terrifying figures who haunt the dreams of folk from the Continent and beyond.

Ithlinne

There are a lot of major facets of the "Witcher" setting that the main story of "The Witcher: Blood Origin" has to establish origin stories for — the biggest and most obvious among them being the Conjunction of the Spheres and the creation of the first Witcher. But the series also finds time to sprinkle in small roles that are destined, as more hardcore fans will undoubtedly know, to become central figures in Witcher lore. One such figure is Ithlinne (Ella Schrey-Yeats), who appears in the series for just a few short scenes as a poor little girl who happens to have psychic visions. As it turns out, that little girl eventually grows into the most famous seer in history — the very seer whose most famous prophecy points to Ciri as the cause of Armageddon.

In the final moments of the series, Ithlinne offers Éile the Lark (Sophia Brown) a prophecy regarding her child and its descendants, and as ominous as its sounds, it's nothing compared to what she'll predict just a few years hence. Unlike so many other oracles, an alarming amount of Ithlinne's prophecies end up coming true, and so her writings become almost sacred texts in the world of the Witcher. Many of the major decisions made by kings, queens, and mages in the time of Geralt come as a result of Ithlinne's words and their ever-present doom — like, for example, the Wild Hunt's pursuit of Ciri, all thanks to Ithlinne predicting Ciri's role in the end times.

Avallac'h awakens

Another minor character in "The Witcher: Blood Origin" who closes out the series in an impactful way is Avallac'h (Samuel Blenkin). For the vast majority of the series, the young Elf is merely a simple mage's apprentice, a stuttering lackey with no discernible importance beyond his meager station. His surprising rise to prominence comes only at the illogical whim of Empress Merwyn (Mirren Mack), who picks him to be her royal mage partially because of his unsuspecting demeanor. Merwyn has no idea what events she's setting in motion by promoting Avallac'h and granting him access to higher-level magical research, nor how he will one day play a major part in the story of Geralt and Ciri.

As fans of the novels and video games will know, Avallac'h is an ancient (which we now know to be about 1,200 years) Elven mage with an unparalleled knowledge of interdimensional travel who eventually becomes Ciri's mentor and bodyguard. In "The Witcher III," it's thanks to Avallac'h that Ciri is able to evade the Wild Hunt for so long, and it's only through him that she's able to understand the truth of her powers and finally (somewhat) master them. By awakening Avallac'h's potential, Empress Merwyn unknowingly sets in motion a series of events that culminate in Ciri's survival and therefore enable Ciri to play whatever cataclysmic role she's meant to.

The Conjunction of the Spheres

The world of "The Witcher: Blood Origin" seems harsh and violent enough for the series' first few episodes, but its finale takes everything to an extreme new level by ushering in the Conjunction of the Spheres. The Conjunction is perhaps the single most important event in the Witcher canon, and even when shown in the series, its full importance goes untold.

The finale shows the Conjunction's first moments, describing it as a shattering of space and time, a tearing of the veils between worlds, but even that grandiose narration doesn't begin to cover it. Almost instantly, the Conjunction transforms the Continent from a place of relative uniformity and stability into a terrifying, savage land where dozens to hundreds of different species of monsters — humans and Elves included — war with each other for supremacy and basic survival. Gone are the days when a peasant's greatest concerns were taxes and blight, replaced with the existential terror of vampires, basilisks, kikimores, and leshys. The establishment of the various Witcher schools is a direct response to this sudden influx of monstrous beasts and without the Conjunction, there would be no Witchers around which to build a franchise.

Humans arrive

As any longtime fan of the "Witcher" franchise can tell you, oftentimes the real monsters aren't the beings with sharp claws, stingers, and rotting flesh — they're the very people around us, the seemingly regular citizens who suddenly resort to ghoulish acts of violence and selfishness. That very paradox, that humanity is the real monster, is one of the central themes that guides "The Witcher" and all the other franchise media. In a clever stroke of world-building, Sapkowski chose to introduce humans to the Continent at the same time as the more obvious monsters, making the creation of the Witchers a dual necessity. In the latter half of "The Witcher: Blood Origin" finale, the Conjunction of the Spheres brings humanity to the Continent, forever changing its landscape (both literally and metaphorically).

In the finale, an Elven fisherman stumbles upon a shipwreck whose passengers speak no Elvish and bear smooth, rounded ears. Those first human settlers, though unintentionally, start a process on the Continent that in many ways resembles an infection, spreading from nation to nation, tearing them down in order to continue feeding and increasing their numbers. The Continent will never be the same now that the longstanding Elven dominion is challenged.

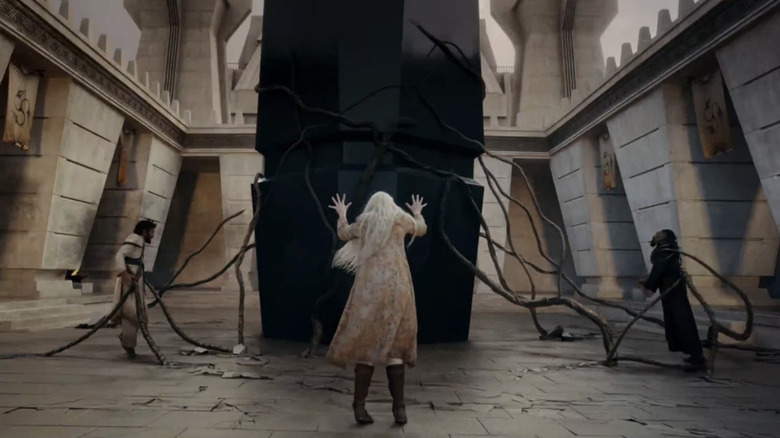

The monoliths remain

One of the more curious new additions to the Witcher lore in Netflix's "The Witcher" is the presence of the monoliths, strange, black pillars of stone that seemingly harbor deep secrets relating to magic and the Conjunction of the Spheres. The video games have their own monoliths which seem unrelated, and the books have no mention of them at all, making them a novel invention for the Netflix series. They pop up again and again in "The Witcher," forming the basis of Istredd's (Royce Pierreson) research, interfering with Ciri's power, and even summoning several entirely new species of monsters. The mysterious structures return in "The Witcher: Blood Origin," and like other important facets of the universe, their true nature and origin is revealed more fully in the series.

It turns out that the monoliths are Dwarven creations, only controlled by the Elves because of their gradual conquest of the Dwarves and their territory. Their magic is ancient, predating even Elvish magic, and is intrinsically tied to the land itself, even the underlying properties of the dimension itself. Just as the monoliths withstood the magical experimentation of the Elves and endured until the time of humanity, they also endured throughout the days of Dwarven dominion and Elvish conquest, making them some of the only unchanging features of the Continent's landscape.

Fjall, the first Witcher

The world of the Witcher is chock full of fascinating characters, creatures, coalitions, and conflicts that make for excellent story material, but at the end of the day, the reason we're here is the Witcher himself, Geralt of Rivia. He and his fellow cat-eyed, sword-slinging brethren provide the franchise with its namesake and are Sapkowski's primary invention. "The Witcher: Blood Origin" is fully aware of this fact, which is why the bulk of its conclusion is dedicated to the creation — and eventual destruction — of the Continent's first Witcher.

Interestingly, the first Witcher wasn't created by any organization in response to encroaching monsters, and it even predates the Conjunction of the Spheres. Instead, the first Witcher is made as a bespoke solution for killing one single monster. Although the process of mutating young boys into Witchers eventually becomes standardized, the first attempt is anything but. Fjall is laid on the dirt floor of a cave, given a mix of herbs, and infused with the blood of the most convenient monster. The transformation ultimately consumes him and leads to his death, making the creation of the first Witcher a less-than-perfect beta test, to put it mildly. How the process was revived and eventually streamlined is still unknown.

One of her blood shall sing the last

Bookending "The Witcher: Blood Origin" are prophecies from the young Ithlinne. The first prophecy centers around the Lark and her quest, but the second prophecy, the one that comes at the tail end of the finale, seems tailor-made for Geralt and Ciri. In particular, the lines about a seed that will "carry forth the first note of a song that ends all times, and one of her blood shall sing the last" are almost certainly a direct reference to the Elder Blood, Ciri, and her eventual role in the ending of the world.

This final prophecy of the series echoes the most famous of Ithlinne's predictions in the books and games. Known in Geralt's time as simply Ithlinne's Prophecy, it foretells the ending of the world, all centered around the Elder Blood. That very Elder Blood is the blood flowing in Ciri — and as far as anyone is aware, only Ciri — making the girl perhaps the greatest asset to anyone in the Spheres who has a stake in Armageddon (in other words, everyone). Like Ithlinne's Prophecy, this prediction from the "Blood Origin" Ithlinne is likely what will (at least partially) set in motion the series of events that lead to future generations' fear and manipulation of those with the Elder Blood, like Ciri.

The Song of the Seven

As "The Witcher: Blood Origin" concludes, Seanchai (Minnie Driver) implores Jaskier (Joey Batey) to "sing the Song of the Seven," referring to the tale she just told him of Fjall, the Lark, and their five companions. Her goal in relaying their tale to the famous bard is for him to spread it far and wide, rekindling the fire of hope among Elvendom that the Lark and company first breathed to life over a millennium ago.

Thus, the series exists for a reason, not just for Netflix and "Witcher" fans, but also in canon. Tasked by the mysterious and godlike Seanchai to sing the Song of the Seven across the Continent, Jaskier emerges from the series with a new purpose, one meant to tip the scales of power toward the side of Elves. Seanchai's nature and ultimate motivations are unclear, so it's difficult to determine exactly why she brought this tale back to life or what will come from it, but regardless, it will certainly mean more for Jaskier, the Scoia'tael, and therefore the state of the world for Geralt and Ciri, in future seasons of "The Witcher."

Brief hints at the future

Despite the fact that the majority of "The Witcher: Blood Origin" is set long before the time of Geralt and Ciri, there are two brief sequences set in their era, one at the series' very start and one at its end. In those few moments, we're actually able to glean a decent amount about the current state of the Continent and its warring inhabitants.

For one thing, we know that the wars in the Northern Continent have for some reason attracted attention from extra-dimensional beings, hence Seanchai's involvement. Further, as Driver has confirmed that she'll be playing Seanchai in more "Witcher" projects going forward, both she and the Song of the Seven are likely to appear in "The Witcher" in future seasons, hopefully with better intent than the other most famous mysterious, godlike being in Witcher lore, Gaunter O'Dimm. In addition, the scene in which we first find Jaskier says a lot about the current state of things. He is apparently regarded as a folk hero, the noble Sandpiper, Rescuer of Elves, and is even beloved enough to warrant his rescue from human capture by an entire company of Scoia'tael. It seems since we last left Jaskier and the rest of our heroes in "The Witcher" Season 2, the Continent has moved forward, elevating Jaskier along with it.