The 12 Best Films That Turn 20 Years Old In 2023

Film buffs love to debate which year was the best in movie history. Partisans will stand behind 1939, the year of "Gone with the Wind," "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," and "The Wizard of Oz," or perhaps 2007, when masterpieces like "Zodiac," "There Will Be Blood," and "No Country for Old Men" stormed arthouse theaters and multiplexes alike. Most of these debates are fairly silly; pointing to any year as the "best" means leaving out the hundreds of films released that year that were terrible or mediocre. Conversely, every single year sees the release of major hits, cinematic milestones, and films that will shape the course of the medium.

2003 is not often on the list of "best film years," but looking at the movies that were released then, one could make the case for it being a transformational year, for individual artists, for studios, and for the way in which films were marketed and sold. 2003 is the year that pointed the course for the next two decades of epic CGI fantasy films, the year that saw at least two majorly influential documentaries, and the year in which the predominant animation studio of the era figured out that it could entertain children and emotionally devastate parents at the same time. Let's take a look at the best films that turn 20 years old in 2023.

The Dreamers

Sex, movies, and politics collide in Bernardo Bertolucci's coming-of-age film, "The Dreamers." Set against the backdrop of the Paris student riots of 1968, the film stars Michael Pitt as Matthew, a young American studying abroad and staying for the summer in the book-and-art-filled flat of fraternal twins, Théo (Louis Garrel) and Isabelle (Eva Green). Left alone by their bourgeois parents, Théo and Isabelle welcome Matthew into their impossibly glamorous life of traipsing through Paris, drunk on wine and youth, endlessly debating film, music, and leftist politics. Matthew falls hard for both Isabelle and Théo but soon learns that the twins have a deeper, more troubling connection to each other.

Perhaps not surprisingly, a film about bisexual French incest was controversial, earning an NC-17 rating — one of a spate of films at the time that tried to turn the adults-only rating into a viable commercial option. 20 years later, Bertolucci's film remains a heady, erotic exception to the rule. It did not inspire a wave of sexy arthouse imitators and is perhaps most notable now for being Eva Green's breakthrough performance. Just 23 at the time, Green commands our attention in every scene; as good as Pitt and Garrel are (and they are very good), they just can't keep up.

The Station Agent

In the 2000s, a mini-genre of American independent film existed; dramedies about isolated men who are drawn out of their shells by a combination of pushy friends and some unusual hobby or job. Take, for example, 2002's "Love Liza," where Phillip Seymour Hoffman's grieving widower is rescued by a group of remote-control airplane enthusiasts.

Tom McCarthy's "The Station Agent" is one of the best entries in this field, a low-key comedy about a depressed man who lives in an abandoned New Jersey train depot. As much as he tries to withdraw from the world, he can't seem to shake an artist (Patricia Clarkson) who keeps nearly hitting him with his car, a pregnant young woman (Michelle Williams) with an abusive boyfriend, and a hot dog vendor (Bobby Cannavale) who insists on being his friend.

The man at the center of all this is named Finbar McBride, played by future "Game of Thrones" star Peter Dinklage in his first lead role. Dinklage had been kicking around film and television for the better part of a decade, often in roles that used his size as a punchline. McCarthy's script doesn't define Fin by his dwarfism, but doesn't ignore it either; he and Dinklage wring both laughter and pain from the small indignities he suffers from other people. The moment when he steps up on a stool and challenges a bar full of giggling yokels is wonderfully cathartic for the audience and announces Dinklage as a star on the rise.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

What a high-sailing franchise we could have had. Patrick O'Brien's bestselling novels about 19th century Royal Navy captain Jack Aubrey and his best friend, surgeon Stephen Maturin, have come to the screen just once in Peter Weir's "Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World." Adapting two of O'Brien's Aubrey-Maturin novels (hence the bifurcated title), the film stars Russell Crowe as the dashing, headstrong Aubrey, captain of the HMS Surprise, and Paul Bettany as his more measured but no less brave companion, Maturin, as they pursue a deadly French privateer that has been attacking British whaling ships in the waters near South America.

Weir staged much of the action on the open sea and filmed its Galapagos Islands sequences on location — the first major film to ever do so, (per movie-locations.com). Crowe and Bettany's warm camaraderie is the heart of the film — may we never forget the lesser of two weevils — but James D'Arcy is a standout as the Surprise's first lieutenant who proves himself in battle.

The film has everything you would want in a gritty, realistic Napoleonic War-era sea adventure which audiences in November 2003 mostly did not. Despite strong reviews and Oscar wins, the film was overshadowed at the box office by fantasies like "Elf," the "X-Men" sequel "X2," and the first entry in the decidedly non-realistic sea adventure series, "Pirates of the Caribbean."

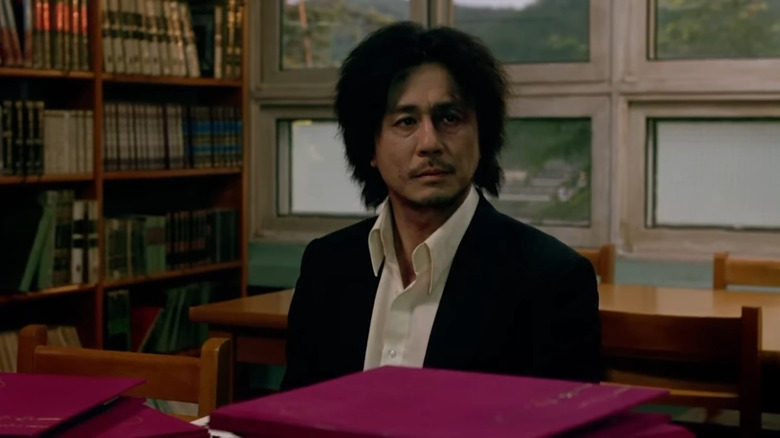

Oldboy

If "Oldboy" were nothing but its brutal, four-minute single-take hallway fight scene — AKA "the hammer fight" – it might have earned a place on this list. Aside from the incredible technical achievement by director Park Chan-wook, its influence can still be seen in fight choreography decades later, most notably in Netflix's "Daredevil" series. When Spike Lee remade the film in 2013, his camera moved in more directions than Chan-wook's side-scrolling video game technique, but other than that, the fight was staged more or less identically. Lee knew not to mess too much with perfection.

But "Oldboy" is more than its shock sequences like the hallway fight, or star Choi Min-sik eating a live octopus on camera. It is a bold and uncompromising thriller, taking its twin revenge schemes to such Biblical (or Greek, rather) extremes that the very idea of vengeance becomes horrible to comprehend. Deadbeat dad Dae-su (Min-sik) is kidnapped in 1988 and held in a hotel room-like prison cell for 15 years. In 2003, after going mad from despair and training his body for vengeance, he is released and given five days to uncover his captor's identity and the reason for his imprisonment. The answers, when they come, are too terrible to live with — not just for Dae-su, but for his sadistic captor and for Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong), a beautiful young chef who falls for him. The only escape for any of them is either a life of blissful ignorance or a bullet.

Kill Bill: Vol. 1

After playing around with '60s kitsch in "Pulp Fiction" and '70s blaxploitation in "Jackie Brown," writer-director Quentin Tarantino went all in on the East Asian martial arts films of his youth with the high-octane genre pastiche "Kill Bill: Vol 1." The film stars Uma Thurman as "the Bride," AKA Black Mamba, an assassin left for dead by her former boss Bill (David Carradine, mostly off-camera here). After being in a coma for four years, she awakens and embarks on a methodical plan of vengeance, not just against Bill, but the other female killers who comprise the Deadly Viper Squad.

Where "Jackie Brown" mostly borrowed from '70s crime movies for its soundtrack and overall vibe, "Kill Bill" is made up almost entirely of stolen parts. It's an amazing pop culture remix, incorporating everything from Bruce Lee's costume from "Game of Death" to the opening credits of the Raymond Burr show "Ironside" to Japanese medieval folk hero Hattori Hanzo, played here by samurai film legend Sonny Chiba.

At the heart of it, though, is Thurman, in arguably the best role of her career; the Bride is in nearly every scene, and her righteous anger propels the film like a needle full of adrenaline to the heart. "Vol. 2," released in 2004, is longer and more Western (both in genre and scope) than its predecessor, but doesn't have the same feeling of seeing something very old, but also very new at the same time.

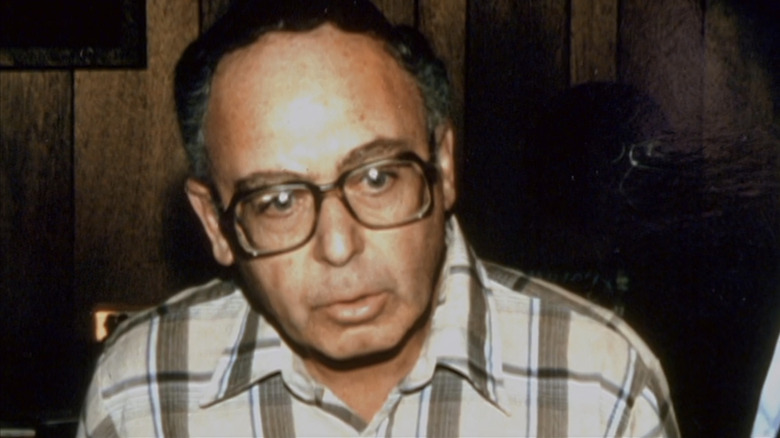

The Fog of War

Errol Morris' Interrotron is an intimidating thing for its subjects. A bulky piece of equipment, it allows the Academy Award-winning documentarian to conduct interviews from a distance while his image is broadcast in front of the subject, allowing them to maintain eye contact with Morris and the camera simultaneously. In a 2004 interview with FLM Magazine (via Morris' website), when Robert McNamara first sat down to be interviewed for the 2003 Academy Award-winning documentary, "The Fog of War," he didn't like the machine and said so outright. "But then he sat down, and we proceeded to record over 20 hours of interviews," Morris said. "I guess he came to like it, too."

For nearly the entire film, McNamara — former Secretary of State under Kennedy and Johnson, and in many ways the architect of America's involvement in Vietnam — stares directly at you, seated just right of center in the frame. The only break from McNamara's gaze comes from stock footage clips of the Vietnam War and World War I and II.

The film is structured as 11 "lessons" that McNamara is imparting to us, but the real subject is not his knowledge but the man himself. Morris allows us to stare into the eyes of one of the most consequential men of the 20th century and draw our own conclusions, whether he is tearfully quoting T.S. Eliot or candidly admitting that the United States committed war crimes in World War II.

The Triplets of Belleville

Disney has long held American animated film in an iron grip, but every so often a feature comes along to remind us that there are other ways to be. 2003 Oscar-nominated film, "The Triplets of Belleville" has the bones of a Disney-type film, or at least reads that way on paper. When Parisian bicyclist Champion (Michele Robin) is kidnapped by mobsters after competing in the Tour de France, his grandmother Madame Souza (Monica Viegas) travels across the Atlantic to rescue him, aided by the eponymous Triplets of Belleville, a trio of ancient women who were popular singers in the 1930s.

But that dry description doesn't begin to communicate the experience of watching the film. Written, directed, and animated by Montreal filmmaker Sylvain Chomet, the world of Champion, Madame Souza, and their pudgy dog Bruno is a singular vision, exaggerated and grotesque but inviting just the same. Madame Souza's flat, tall and thin and constantly rattled by passing trains, is perpetually mud-colored, while the countryside where the race begins pops with the colors of the French flag.

Champion is a wiry man with giant legs, while Madame is his visual opposite, squat with little tiny legs — one longer than the other — poking out of her dress. Despite a sensibility that Roger Ebert described as "the Marquis de Sade meets Lance Armstrong," though, the film is unexpectedly sweet and ends with a touching tribute to parents (and grandparents) long gone. Disney would be proud.

Capturing the Friedmans

What do we really know about another person? A close friend? A parent? How could someone who has loved us and cared for us for our entire lives have a different side to them, a monstrous side? And does that disqualify or taint the love that they may have shown us? These are the terrible questions that power Andrew Jarecki's true-crime documentary "Capturing the Friedmans."

In 1987, high school science teacher Arnold Friedman was arrested for possession of child pornography, and he and his oldest son Jesse were accused of pedophilia and sexual assault. The case made headlines and rocked the Long Island suburb where they lived. Arnold always maintained his innocence, though, and evidence of police misconduct in the case left room for a sliver of reasonable doubt.

It's a compelling, if awful, story on its own, but what makes it such a great, troubling film is the fact that one of Friedman's younger sons, David, had a camcorder and filmed nearly everything surrounding the arrest and trial. This treasure trove of footage, however, doesn't elucidate the facts of the case — in fact, it often muddies them even further, as the specter of the crimes makes any moment of Arnold on screen, even doing normal everyday things, feel sinister. When imagery can take on so many different meanings, how can the truth ever be uncovered? It's a question the film cannot answer.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.

American Splendor

"Look, before we get started with any of this," Harvey Pekar (Paul Giamatti) says to his future wife Joyce Brabner (Hope Davis) when they meet in person for the first time, "you might as well know off the bat that I had a vasectomy." The compelling combination of bluntness and vulnerability in that line is both Pekar and his biopic, "American Splendor," in a nutshell.

Pekar was a clerk at an Ohio VA hospital in the 1970s when he started drawing comic strips and hawking old records on the side. His friendship with underground comic book artist Robert Crumb (James Urbaniak) inspired him to create an autobiographical comic, also titled "American Splendor," and its success made him a star in the alt-comic world; to the general public, he was probably best known for a number of combative appearances on "Late Night with David Letterman" in the '80s.

To tell his cinematic life story, including his 1990 cancer diagnosis, writer-director Shari Springer Berman and co-director Robert Pulcini use three different versions of Pekar: Giamatti's performance, with its slouching posture and angry midwestern croak; Pekar himself, commenting on the action via behind-the-scenes "interviews" conducted by Berman; and a black-and-white animated version of Pekar's comic book self, butting in from time to time on the live-action retelling. The strength of the screenplay is matched by the uniformly excellent performances from Giamatti, Davis, and Judah Friedlander as Pekar's friend and self-described "genuine nerd," Toby Radloff.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King

With Disney churning out epic Marvel movies at a steady clip for over a decade, it's easy to forget what an incredible achievement Peter Jackson's "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy was. Not only did the New Zealand filmmaker, best known at the time for gross-out low-budget horror-comedies like "Meet the Feebles," successfully adapt a series of novels long thought unfilmable, but he also released each film annually, starting with 2001's "The Fellowship of the Ring" and 2002's "The Two Towers."

Armed with state-of-the-art digital technology and an ensemble that included Elijah Wood, Viggo Mortensen, Cate Blanchett, Liv Tyler, and Ian McKellan, Jackson brought the world of J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-Earth to vivid life. 2003's "The Return of the King" brings the fantasy epic to a close, concluding the story of young hobbit Frodo Baggins (Wood) and his quest to destroy the powerful, corrupting One Ring in the bowels of Mount Doom. (And then it concludes again, and again, and one more time for good measure.)

The film boasts chilling setpieces — as when Aragorn (Mortenson), the titular returning king, raises an army of ghostly soldiers to aid in the war against the evil Sauron — and thrilling battle scenes whose influence can be seen in the "Avengers" movies' massive team-ups. In a rare moment of critical and popular consensus, "The Return of the King" also won Best Picture (plus ten other awards) at the 2004 Academy Awards.

Finding Nemo

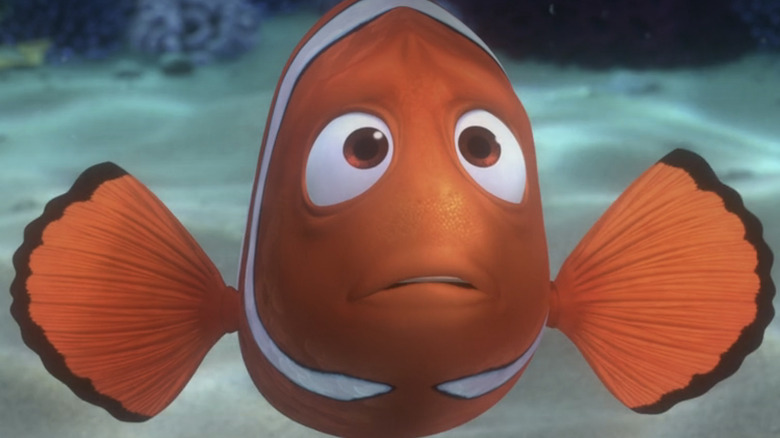

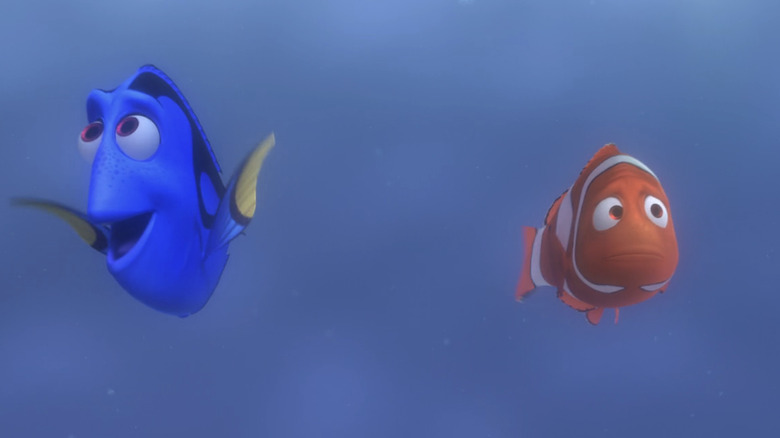

Over the last two decades, Pixar films have developed a reputation for entertaining children while emotionally devastating adults. From the short film of love and grief that begins "Up" to the tragic fate of imaginary friend Bing Bong in "Inside Out," grown-ups know to keep their Kleenex handy when firing up the studio's latest offering. But in 2003, Pixar wasn't yet known for traumatizing parents.

That all changed with "Finding Nemo," which begins with Marlon, a clownfish with big dreams voiced by Albert Brooks, losing his wife and all but one of their eggs to a terrifying barracuda attack. Years later, Marlon has grown agoraphobic and overly terrified that his young son Nemo will get hurt. But when the worst happens and Nemo is captured by a fishing boat, Marlon must gather his courage and set out across the ocean to rescue his son.

Directed by Andrew Stanton and Lee Unkrich, "Finding Nemo" is primarily a road picture, with Marlon joining forces with a forgetful blue tang named Dory (Ellen DeGeneres) and facing off against sharks, whales, seagulls, and more. Meanwhile, Nemo (Alexander Gould) stars in his own prison escape movie, trapped in an Australian dentist's tank alongside stern lifer Gill (Willem Dafoe) and a menagerie of sea creatures desperate to swim free. But through it all, the adventure and comedy are rooted in, and made richer by, very real emotions. Brooks' vocal performance as the perpetually panicked Marlon is a standout, simultaneously hilarious and harrowing.

Lost in Translation

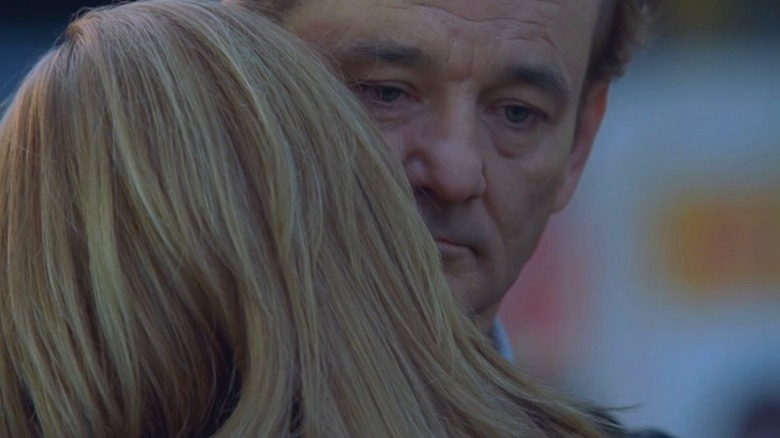

Before 2003, Bill Murray had already displayed his deadpan, melancholic side in his collaborations with Wes Anderson, "Rushmore" and "The Royal Tenenbaums," and long before that in the little-seen 1984 drama, "The Razor's Edge." Scarlett Johansson had graduated from child actor roles with mature performances in "The Man Who Wasn't There" and "Ghost World" two years earlier. Writer-director Sofia Coppola had already announced herself as an auteur in the making with 1999's sensitive, elegiac, "The Virgin Suicides." And yet for all three artists, "Lost in Translation" feels like a breakthrough, a statement of purpose that would define not just the next two decades of their respective careers, but the next two decades of independent film.

Bob Harris (Murray) is a middle-aged Hollywood star working in Tokyo who strikes up an unlikely friendship with Charlotte (Johansson), a similarly adrift young newlywed staying in the same luxury hotel. The two have potent chemistry together, and while Bob and Charlotte's connection isn't romantic, it's not not romantic either. Coppola films Tokyo as if it were an alternate universe, where everything is just familiar enough to be uncanny, but is ultimately more interested in her American characters' alienation than the setting that spurs it. And, it must be said, there are a handful of moments — like Bob's misadventures with a sex worker — that indulge in some tacky racial humor. Nevertheless, the film is a triumph for all involved and a high-water mark for film in the last 20 years.