The Ending Of The Devil Conspiracy Explained

The eternal battle between good and evil gets a technological twist in the religious action thriller "The Devil Conspiracy." Canadian director Nathan Frankowski and first-time screenwriter Ed Alan tell the story of Laura (Alice Orr-Ewing), an American art student and avowed atheist studying in Turin, whose life is forever changed when she is swept up in a sinister cult's plan to free Lucifer (Joe Anderson) and his army of demons from hell and destroy the world. Her only hope is heaven's greatest warrior, the archangel Michael, who comes to Earth in the body of a recently murdered young priest (Joe Doyle).

The film is a mishmash of influences, drawing on everything from the "Omen" series (particularly its New World Order-focused sequel "The Final Conflict") and "The Exorcist" to "Terminator 2" and modern day superhero films. Along the way, Alan's script insists that the angels and demons found in religious art — including, one assumes, those in this very film — are not metaphors for the human condition, but literal creatures waging literal war. By the end Lucifer has once again been caged by his own pride and hubris, but horror movie fans know that no great monster — especially the greatest monster — is ever truly down for the count. Let's take a look at the end of "The Devil Conspiracy," from its explosive highs to its perplexing lows.

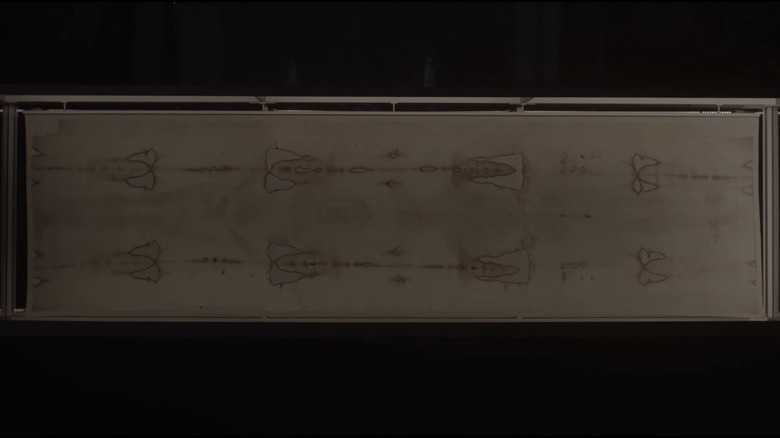

The Shroud of Turin

At the heart of both the film and the cabal of satanists' evil scheme is the Shroud of Turin, a long piece of linen bearing the blood and outline of a man's body that has long been believed by some to be the burial shroud placed over the body of Jesus following the crucifixion, and from which he rose from the dead after three days. Housed at St. Michael's Cathedral in Turin, the film's plot kicks into gear when the Shroud is put up for public display for the first time in decades. Seizing upon this moment of relative exposure, Lucifer's minions break into the Cathedral after dark and steal the Shroud, killing young Father Marconi (Doyle) and taking Laura prisoner.

For the film's conceit to work, one must go along with the following points: That the Shroud is an actual relic of the resurrection, that the DNA of Jesus lives in the stains of what appears to blood, and that the DNA could be sourced in order to engineer a clone of Jesus. While the final point is science fiction hokum (at least, for now), the first two have been a source of controversy for centuries. While nearly all historical and scientific analyses conducted on the Shroud have placed its origins in the 13th or 14th century, making it a forgery from over 1,000 years after the death of Jesus, religious believers have long maintained its legitimacy and its power as a symbol of faith. As far as the film is concerned, the Shroud is the genuine article; not even noted skeptic Laura dares question its legitimacy. Accepting the Shroud's provenance, at least in the context of the film, is the price of admission.

Saint Michael vanquishing Satan

The film's use of the Shroud as a MacGuffin is in keeping with its overall theme of the literal power of imagery. Early on, Father Marconi tells Laura that he views art as both a record of the past and a guide to the future — which is a maddeningly simplistic take on the value and purpose of art (especially religious art), but at least it serves the thematic purpose of the film. Frankowski borrows imagery from both the sacred and secular realms, most notably the traditional Catholic motif of Saint Michael defeating Satan. The film begins with a dramatization of the event, with actor/martial artist Peter Mensah playing Michael in his celestial form; later, when Laura is visiting the Cathedral and sketching a sculpture of the battle — one with a working, removable sword for some reason — Satan's head comes to life and moves slightly, just outside of Laura's peripheral vision.

Saint Michael's battle with the devil was a frequent subject of Renaissance art for centuries. Arguably the best known painting of it was by Raphael in the early 16th century. The painting depicts a winged Michael standing atop Satan in victory, with a sword on his hip and a spear held above the devil's head. Other paintings and sculptures over the centuries have adopted this same basic pose, sometimes with an added detail of Michael carrying golden chains with which to hold Lucifer prisoner. The film uses the sword and the golden chains as a plot point, as they are what keep Lucifer a captive in hell, until a mysterious earthquake rattles the chains loose and brings him one step closer to freedom.

Blood Libel

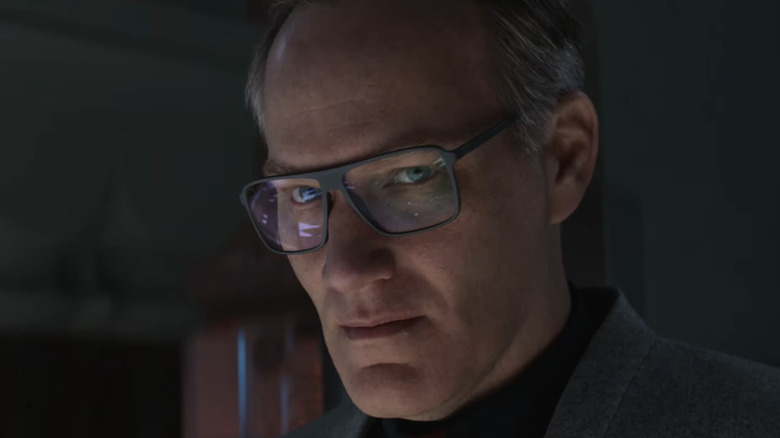

So, who exactly is aiding Lucifer in his bid to rule the world? Why, a bloodthirsty cabal of shadowy child-sacrificing elites, of course! Symbolized by an ever-present inverted triangle insignia, this group presents to the world as a groundbreaking biotech company operated by the sinister Dr. Laurent (British character actor Brian Caspe), while behind the scenes they are led to do the devil's bidding by white-haired Liz (dancer Eveline Hall) and the mute, monstrous Beast of the Ground (Spencer Wilding).

Fears of innocent Christian children falling prey to ritualistic sacrifice have fueled conspiracy theories and violence for centuries. In the 1980s it manifested in "Satanic Panic," where heavy metal music and Dungeons and Dragons games were evidence of the devil's pernicious influence. More recently, QAnon and Pizzagate conspiracy theories implicated high-ranking politicians and celebrities in an imaginary sex abuse cult. But the root of these modern-day panics can be traced back to the "blood libel," the seemingly deathless belief that Jews use Christian blood in their food and religious practices, which has provoked anti-Semitic violence the world over. While Alan's script does not mention the blood libel directly, history has shown that the very idea of a dark conspiracy carried out by wealthy globalists often has its origins in anti-Semitic thinking; audiences need only read between the lines.

A better Jesus

The role of this biotech company in the cult's master plan is a little murky; in fact, by the end of the film it can be difficult to parse exactly what Liz and the Beast of the Ground had in mind, or how long they have been working toward it. According to narration by the grizzled Cardinal Vincini (James Faulkner), the cult has been attempting to find an infant host for Lucifer to latch onto for centuries, if not millennia, but no matter how many babies and pregnant women they lower into the pit at the bottom of the devil's fortress (conveniently located not too far from Turin), none were ever strong enough to bear Lucifer's weight. The teenage refugees seen in the pit along with Lucifer and his demons appear to be the souls of the babies who were sacrificed, though this plot point also remains unclear.

The biotech company seems to be the perfect next step in the cult's plan. Rather than hope for a perfect natal specimen, they will craft one from the DNA of the one human who would be strong enough to hold the prince of darkness: the prince of peace. "A new Jesus," Liz explains to Laura after she has been impregnated. "A better Jesus." Other than a brief, somewhat humorous scene of the cult auctioning off a baby clone of Michelangelo for millions of Euros, however, the film loses interest in that entire plot thread. The "conspiracy" part of the devil conspiracy ends up being something of a red herring.

How much time has passed?

A thriller need not explain every single aspect of its plot in order to be successful. "The Big Sleep," for example, one of the most beloved detective films of all time, has a plot that's almost impossible to fully follow; even director Howard Hawks apparently wasn't 100% clear on every detail. But there are a few things that do need to be clarified for an audience to be able to follow the action, usually questions of time and space that orient us in the film. The first scene of the film takes place thousands of years in the past, while the last scene picks up five or so years in the future. In between, however, it's not very clear exactly how much time passes.

Once Laura is impregnated with the clone of Jesus that will serve as Lucifer's earthly host, viewers watch as the pregnancy progresses and the devil takes control of Laura's body. Based on the pace of the rest of the film up until, it would appear that she is gestating at a supernaturally fast pace, going from fertilization to full term within days, if not hours. But the film doesn't confirm that this is the case, and since Michael is trapped in hell for most of Laura's pregnancy, it could just as likely be that this part of the film is a montage over the course of 40 weeks.

La Pietà

In the moment just before Laura/Lucifer gives birth, when Michael has been gravely injured and it seems evil has won the day, she holds his body cradled in her lap. Frankowski shoots this moment straight ahead, and the allusion is clear: He has positioned them like La Pietà, Michelangelo's iconic sculpture of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus' dead body after the crucifixion. Like Saint Michael defeating Satan, this is clearly a deliberate visual reference, but the values have been inverted. Instead of a moment of love and comfort, it is a gesture of hatred and defeat. In the context of the film, it's almost a joke.

There is very little humor in "The Devil Conspiracy," despite its potential for campy fun; nearly every scene is as po-faced as Michael, who is an archangel by way of a Terminator. And when there is a conscious attempt at humor, it is often in the form of inane comebacks, as when Lucifer whines "Was that really necessary?" as Michael chains him to a rock at the beginning of time. Every so often, though, a spirit of wit seeps into the proceedings. Laura and Michael's Pietà recreation is one of those, or when Michael hops in the late Father Marconi's car and the INXS classic "The Devil Inside" comes on the radio. He switches stations and lands on Real Life's "Send Me an Angel."

No one must know

At long last, Lucifer's human host has been born. Liz presents the screaming newborn to Dr. Laurent and the other cult members, who kneel in reverence. But little do they know that their part of the devil conspiracy has come to an end. By Lucifer's orders, no one must know of what took place at this fortress, so the Beast of the Ground takes his preferred weapon — a razor-sharp triangular blade attached to a long chain — and brutally murders every cult member, including poor Dr. Laurent, who surely thought he had worked his way into the devil's favor.

Before this moment, there had been a fair amount of violence in the film, but most of it of the PG-13 superhero variety, where people get beaten up or shot without much outward sign of pain or injury, and very little blood. This scene is different, however, and the sudden lurch into flayed skin and bloody horror can't help but recall the 21st century's most popular religious film, Mel Gibson's ultraviolent Easter pageant "The Passion of the Christ." Even before that, though, Bible epics have often indulged in displays of sex and violence under the guise of history or a strong moral message, from the early films of Cecil B. DeMille to Bruce Beresford's decapitation-happy version of "King David" starring Richard Gere. Infusing Old and New Testament stories with buckets of blood and guts is a tradition, it seems, as old as Hollywood itself.

Michael gets his old body back

Part 2 of Lucifer's plan to cover his tracks is to detonate explosives around the fortress after his demons have reemerged from the hell pit. But that plan hits a snag when Michael, thought to have been killed, survives long enough to get Laura (also thought to be dead) and her newborn into a car and down the mountain. With his last ounce of strength he detonates the explosives before the rest of the demons are able to escape, destroying the body of poor Father Marconi. Freed from his mortal shell, Michael returns to hell in his angelic form to fulfill his promise to escort the refugee souls to heaven.

Except, he had already returned to his angelic form earlier in the film. After being trapped by Lucifer, Michael-as-Marconi sits captive in hell for however long Laura's gestation was — days, weeks, or months — before turning into his celestial self after retrieving his sword. And then he turns back into Michael-as-Marconi when he passes through the entrance of the hell pit back to the real world. If that doesn't make very much sense on the page, it makes just as little sense on the screen. It feels as if the film enjoyed the catharsis of Michael restoring his angelic form so much that it simply did it twice, logic be damned.

A new homily

Laura and Cardinal Vincini return to the Cathedral of St. Michael, Shroud and baby in hand, as the hapless Bishop Bustamante (Pavel Kriz) gives a homily about, what else, the existence of angels and demons and the importance of recognizing their literal existence in the 21st century. His words catch in his throat when he sees this motley duo returning with the Shroud, and when he notices the baby, he can ask only, "What child is this?"

Laura, whose hair fell out during the pregnancy as Lucifer raided her body for energy, wears a shawl around her head. What once was a young, carefree atheist is now a solemn mother, stooped by the burden of cosmic responsibility. The moment calls back to not only the start of the film, when Laura argued with both her lecherous professor and with Father Marconi that Catholic art must be metaphorical because angels and demons aren't real, but to its main themes of sacrifice and taking religious art — and by extension, the scriptures — as literally as possible.

Another Devil Conspiracy?

But Laura and the Cardinal are not destined to live their lives dour and hairless. The final scene flashes forward several years, where the two of them are joyously playing in the woods with a young dark-haired boy named Michael. As Michael helpfully explained earlier, Lucifer was done in by his own hubris. He thought he was God's equal, and that the only mortal body suitable to hold him was that of Jesus.

He was right, in a sense. The body of Jesus was the only one strong enough to hold Lucifer — captive, that is. He had not counted on the innate goodness and power that a clone of Jesus would possess. Now, instead of being chained to a stone in the afterlife, Lucifer is held prisoner within the body of a five-year-old Christ. But prisons, even almighty ones, are made to be escaped from. In the film's final moments we see that Liz survived the destruction of the fortress and has found her master once again. She calls his name from a distance, and a serpent made of smoke and fire slithers from the boy's mouth. Could there be another devil conspiracy in the works? That remains to be seen.