Today's Studio Tax Write-Off Craze Is A Terrible Omen For The Future Of Hollywood

In 1967, or so the story goes, a disappointed Lucille Ball hopped a plane to Miami. Against the advice of her board of directors, she'd gambled on and stood by an odd new sci-fi series in whose yet-to-be proven value she fervently believed in, but whose per-episode cost drained her beloved Desilu Productions. Unwilling to give up on the series, she was eventually forced to sell Desilu to a company then called Gulf + Western. Under its new, more corporate ownership, the fledgling series' hackneyed third season failed to earn it a renewal, much to the relief, insiders say, of the company itself. In syndication, however — and just as Ball (who knew a thing or two about syndication) predicted — the series thrived, and in 1979, its begrudging owners released the first feature film of what would become a lasting, celebrated film and television franchise (via Smithsonian Magazine).

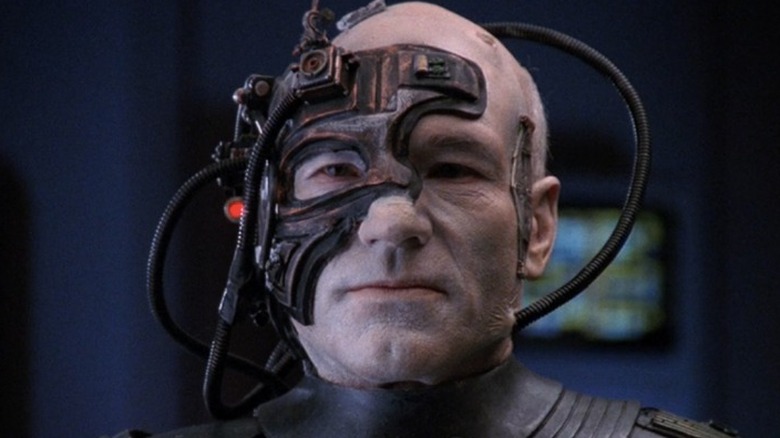

The series was Gene Roddenberry's "Star Trek" — one of the best surprise success stories ever told — and the production company that let it die (only to later make billions and billions of dollars off its various installments) was Paramount. "If they had their way," says Ralph Senensky, a director on the original series, "they would have killed it off. It survived in spite of them."

It's a tale as old as the industry itself, and one shared by countless films and series over the years. But in light of the recent trend of using productions as cannon fodder for tax write-offs (aka, "Batgirling" a project), the specific trajectory of "Star Trek" — and all we'd have likely lost were the series in a similar position today — is worth noting, since they bring the amorality, counter-productivity, and inevitable cultural cost of such a trend into stunning relief.

What's all this about tax write-offs?

The devastating impact the Covid-19 pandemic had on the entertainment industry in 2020 was far-reaching, multifaceted, and intricately tied to (and further complicated by) the challenges posed by the similarly complex streaming boom (per The Los Angeles Times). In the wake of all this profit loss, several big media companies have — in an effort to save money — begun pulling the plug on a project mid-production, or even post-production, reversing renewal decisions, and removing old seasons from streamers.

It's a disturbing trend whose implications and ramifications range from the immediate, obvious, and ethical, to the more insidious, profound, and cultural. And, given Warner Bros. Discovery's "Batgirl" fiasco and notorious gutting of HBO Max, AMC's recent 180s, and John Landgraf of FX's subtle defense of such measures (per Variety), it's also a trend that shows no sign of stopping without some serious intervention. As "Roswell, New Mexico" creator Carina Adly Mackenzie notes in a recent thread on Twitter, the fact that such measures are legal, and have been used sparingly before, doesn't justify their use, nor excuse the increasing frequency with which they're being deployed.

Is it...really that big a deal?

Imagine you've put a year or more of your life and career into a project, as "Batgirl" directors Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah — and the entire cast and crew, including Leslie Grace and Ivory Aquino — did. And imagine that throughout that year (to paraphrase Mackenzie) you've likely been forced to make countless compromises when it comes to your work, because a corporation with wildly different priorities and standards of success ($$$) has insisted you do so — and, more importantly, assured you that if you do so, they'll market and show that work.

Now imagine that on the cusp of your art finally seeing the light of day, it's used as a tax write-off instead. You, the artist, don't ultimately benefit from said write-off, and the corporation that just (let's not mince words here) lied to you not only benefits immensely, but justifies its abhorrent misuse of your work by insisting it would have failed anyway. This is the trend we're dealing with, and one numerous Hollywod creatives have begun speaking out against, even as corporations dance jargon jigs around its merit:

"The decision to not release 'Batgirl' reflects our leadership's [CEO David Zaslav's] strategic shift as it relates to the DC universe and HBO Max," said a spokesperson for Warner Bros. Discovery (whose merger left the conglomerate searching for $3 billion). The spokesperson then applauded Grace's performance in the film — which was essentially complete when WBD turned it into grist — and reiterated the company's gratitude for the cast and crew (via The Hollywood Reporter).

Surely, there's a reason for all this slaughter

Reportedly, that "strategic shift" was a move away from big-budget streaming films back toward theatrical releases. "Couldn't they have just released 'Batgirl' in theaters," you ask? No, silly, because it didn't cost enough money to make. The film's $90 million dollar budget (less than half of "The Batman," but $5m more than "Birds of Prey") meant it was too pricey for a streaming release and not pricey enough for a theatrical one. Numerous outlets, including Variety and Insider, say execs didn't feel such a mid-range budget could meet the theatrical expectations to which DC moviegoers have grown accustomed, and they therefore couldn't possibly justify the $50+ million it would take to market a theatrical release.

In other words: it's our fault, kids. It's our fault this potentially groundbreaking film and its several important firsts (per NBC) got sent to the IRS, and not our local theaters. If only us moviegoers could accept and turn out in requisite numbers for a film made on such a "shoestring" budget — like we've so often done for films good enough to warrant it, even when the budget truly was low — then WBD's hands wouldn't have been tied. A soulless corporate machine didn't kill "Batgirl," the argument goes — no, we did.

This, obviously, is nonsense, but blaming this trend on anyone and anything other than pure greed has become a trend in its own right.

Oh, it's money. The reason's money.

After insisting that FX had no immediate plans to take such measures, Landgraf told the Television Critics Association that the network "wouldn't rule anything out," adding: "There's a long process of optimizing how you tell stories and how you distribute stories through that technology (...) "Film [is] figuring it out again. You just can't take this infinite amount of money and dump it on something. For one thing, it gets stale."

Neither of these so-obvious-they're-meaningless statements justify putting artists through an entire production only to rip it out from underneath them. And Landgraf's use of the world "stale" is painfully ironic. You know what else gets stale for us viewers (other than non-explanations that underestimate our ability to see them as non-explanations)? Being fed the same safe storylines over and over and over again, then being told it's because that's all we'll watch.

Of course, a discussion of these trends must necessarily involve a discussion of what sort of standards companies use to determine whether or not a project will be "worth it" financially, since it highlights the short-term thinking taking root in a post-pandemic Hollywood. The implication — though not necessarily the reality — is that by dropping these (supposed) inevitable financial failures, a company is able to save and redirect money toward projects that aren't destined to fail.

Are they at least *inadvertently* saving us from Bad Content?

What seems to be missing from this pseudo defense is who decides what's "destined to fail," what it means to be a failure, and on what, exactly, that definition is based. These are important pieces of the puzzle, and their recent evolution is both relevant to the future of storytelling and integral to the industry's book balancing.

Take, for example, Netflix (who has itself reversed renewal decisions, per Comic Book and Deadline). There's a reason Netflix cancels so many shows, often right after the Season 2 mark, and it has depressingly little to do with the quality of the art. Wired's Alex Lee explores this phenomenon in depth, but the short version is: thanks to the very same bonuses Netflix uses to lure creators in, a third season of a series costs the streamer far more than a first or a second. Commissioning a new series thus makes more financial sense than renewing a series (even a popular or high-quality series, such as the socially relevant and innovative "Warrior Nun") that isn't meeting their viewership standards.

Unless the vast majority of Netflix subscribers — as opposed to a slightly more specific audience — are going to watch and complete a series within its first 28 days (per Vulture), its renewal isn't seen as worthwhile. In other words: if it doesn't instantaneously appeal to the greatest number of subscribers possible, it gets the axe.

The future of visual narrative is... Applebees

While Netflix's "bonus" bait and switch approach doesn't necessarily rise to the same level of deception that dumping or pulling completed projects does, their notion of success and the metrics used to determine it speak to the increasingly visible divide between artist/audience and producer/platform.

As anyone who has ever eaten or worked at a massive restaurant chain can tell you, the wider the range of your target demographic, the safer you have to play it when it comes to your product, marketing, and ethos. There's simply no room for the groundbreaking, unique, provocative, or potentially "divisive" on a menu meant to cater to literally everyone, everywhere, ever. Certainly, there are many elements of our society — healthcare, for example, or public education — that should cater to and meet the needs of the largest number of people possible. But with regard to art, it is and has always been the works that push boundaries, offer new insight, and voice fresh perspectives and techniques — works that, as a result, don't necessarily instantaneously appeal to or uphold the status quo — that have moved both their mediums, and their viewer, forward.

Again, the war between art and commerce is nothing new, and the gap between the motivations and priorities of those financing the art, and those bringing that art to life — or loving that art — has always been vast, treacherous, and unforgiving (R.I.P., "Raised by Wolves"). But the methods and technologies that corporations can now use to justify and dictate their dismissal of that art have changed, and are giving commerce a major leg-up in that war.

Never tell them the odds

The widely reported list of revolutionary films and television series that bean counters and corporate naysayers have almost killed over the years (almost being the key word) is revealingly long, and includes (but is hardly limited to): Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho," AMC's "Breaking Bad," and, perhaps most famously, a quaint little space movie about an ideological skirmish in galaxy far, far away (per Vanity Fair). The history of film and television is littered, if not defined by, woefully underestimated narratives that far exceeded their expectations (e.g., "The Exorcist," "Moonlight," "Game of Thrones," "Get Out," "Jaws," and several of NBC's biggest hits, including "Seinfeld").

Which is to say: yes, the fact that a film or series has been officially picked up or even completed has never guaranteed that viewers will see it. However, it's also never been so easy for backers and platforms to prematurely determine a project's value, nor so popular for media companies to transform a "cutting of losses" into a source of revenue.

Reliable mediocrity and mass (aka, necessarily watered down) appeal aren't simply, as they've always been, reassuring and alluring to these businesses, but far easier to sponsor pushing in the wake of the pandemic's impact on the industry. Worse yet, this is happening at a time when said reliability is becoming ever easier, and faster, to determine.

Especially in a world where resistance is futile

Move over, test audiences. In 2019, The Verge reported that production companies had begun using AI — specifically, algorithms — to help them determine which movies to make. Fair enough. Human response to art (as in, the very reason art exists and has value in the first place) is subjective, emotional, fallible, and subject to change with changing social contexts and attitudes. Better to use a machine — a thing wholly incapable of understanding the emotional, subjective landscape in which quality art thrives and both reflects and impacts society — to make those decisions for us.

Algorithms already make all our other decisions, so what's one more?

This sneaky little tech trend — in conjunction with the other puzzle pieces mentioned herein (to recap: the industry's new favorite tax write-off trick, the increased emphasis on instantaneous viewership over all else, and corporations' increased ability to calculate and predict instantaneous viewership) — should, at the very least, be the canary in the coal mine — a warning of what the future holds, if these interconnected mechanisms gain further traction.

This lack of risk won't be worth the reward

Some will wonder why it matters — why it matters to "Art," that is — that this should happen (most infamously), to a superhero movie. After all, isn't the overwhelming abundance of superhero movies, series, and franchises the problem?

No. The overwhelming abundance of superhero movies, series, and franchises is a symptom of the underlying problem, and the fate of "Batgirl" (and other completed or agreed upon projects) reveals both just how bad the problem has gotten, and where, if left untreated, it will inevitably lead. That problem isn't superheroes, or the fact that profits are dictating the visibility of art (as they have in the industry since it first became "an industry"). The problem is that the risk-aversion typically employed by networks, production companies, and media conglomerates — an aversion that was traditionally balanced by the idea that rewards require risk — is edging ever closer to absolute and total risk avoidance. And why shouldn't it, when the stakes are so very, very low? Release the movie, don't release the movie. Air the season, don't air the season ... to the corporations that once had to gamble on a project's success, the ability to profit off its pre-and-self-ensured "failure" is infinitely more appealing.

Unfortunately, while profits can be made in a world without stakes, art — as in, stories that move, change, or inspire us — simply cannot.

Art is meant to save us from ourselves, but can art be saved from The Bottom Line?

Let's go back to the story that opened this piece. There are two ways of looking at Lucille Ball's steadfast refusal to terminate "Star Trek," and they highlight two very different "bottom lines."

The Powers-That-Be in Hollywood might well consider it exactly the kind of cautionary tale that justifies their actions (read: if you back a sinking ship, odds are, you're going to go down with it, as Desilu unfortunately did). But when we consider the multiple generations for whom "Star Trek" would come to mean so much — when we tally up the countless fans for whom Roddenberry's untested vision was so important (including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who famously convinced Nichelle Nichols to stick with the struggling series, per NPR) — the bottom line becomes less calculable, yet somehow more obvious: That in that stagnant, new world wherein artistic cowardice is so easily rewarded, and the incentive to take risks so efficiently removed, there's simply no need for innovation or progress. No room for stories that boldly go where none have gone before, and that inspire us (despite our initial reluctance or unwillingness) to believe humanity might actually be capable of more than our current shortcomings would suggest.

Would "Batgirl," or any other number of bottom line-beaten works and tax write-offs, have had such an impact? Reader, that's precisely the problem: we'll never know.