Directors Who Hate Their Own Movies

The movie business is one of the most collaborative environments in the world. By the time a film makes the long journey from pre-production to theaters, it's likely that dozens of people have put their own little stamp on the final project. Because of this, when a film turns out well, there are dozens of people to thank for that success. Of course, when a film goes bad, the list of the blamed gets considerably shorter.

Even with so many cooks in a movie's proverbial kitchen, the first in line for the title of "fall guy" is usually the film's director. More often than not, that blame is merited. While some filmmakers seem more or less content to remain quiet and let the quality of their films speak for themselves (good or bad), sometimes a director's silence doesn't quite say enough. Here are a few famous directors who hate their own movies — and let the audience know using some seriously choice words.

Josh Trank — Fantastic Four

Prior to releasing his stylish found footage sci-fi drama Chronicle, Josh Trank was just another up-and-coming filmmaker with little more than a couple of film credits to his name. Once Chronicle arrived in theaters — scoring big with critics and raking it in at the box office — Trank became one of the most revered young filmmakers in Hollywood virtually overnight.

The problem with overnight success is that it heightens expectations for a filmmaker's next project. For Trank, that project was Fox's reboot of their Marvel property Fantastic Four, and expectations were sky high that Trank would deliver a unique opening chapter in the would-be franchise.

That didn't happen. Per some reports, Trank had trouble adjusting to the epic scope of the project and the intense studio scrutiny that came with its equally epic budget. Those same reports claim the young director was, "erratic," "indecisive," and "isolated" throughout much of the film's production. They also claim he was removed from Fantastic Four's editing process by Fox brass.

Behind that news, and the film's pre-release critical drubbing, expectations were tempered to say the least. Then, on the eve of the film's premiere, Trank took to Twitter to completely disown the movie by stating, "A year ago I had a fantastic version of this. And it would've received great reviews. You'll probably never see it. That's reality though." Though Trank quickly deleted the Tweet and played down the situation in the weeks after, he's never actually rescinded that statement.

Ti West — Cabin Fever 2: Spring Fever

Speaking of up-and-comers who had trouble making the jump to larger scaled productions, say hello to indie horror guru Ti West. After making a name for himself with a couple of hard-hitting micro-budget thrillers, West eventually got the call to direct the sequel to Eli Roth's horror hit Cabin Fever.

Though he'd later regret taking that call, West jumped at the chance. And his initial experience on Cabin Fever 2: Spring Fever was quite positive. In fact, pre-production and principal photography on the film went off without a hitch. West and his crew finished shooting the film in April of 2007, but Spring Fever didn't hit theaters until the fall of 2009.

Why the holdup? Seems financial problems at Lionsgate Studios stranded Spring Fever in editing limbo. After a few months, West gave up on ever finishing the film and moved on to his next project, 2009's The House of the Devil. Once Lionsgate got their house in order, they recut Spring Fever sans West. Per the director, the new edit (complete with reshoots he was also not involved with) was "so hijacked" from his original vision that he lobbied to have his name removed from the film altogether.

That request was denied. Though West still works with many of the people he met on Cabin Fever 2, he now considers it "a mediocre movie" that feels like "Dane Cook telling Seinfeld jokes." We're assuming he'd be the Seinfeld in that scenario.

Joel Schumacher — Batman & Robin

In the pantheon of films that have been disowned by the people responsible for making them, few have been more thoroughly dissed than Joel Schumacher's nipple-suited franchise-killer Batman & Robin. In the 20 years since Schumacher's cartoonish, neon-drenched version of The Dark Knight hit theaters, the film has remained one of the biggest punchlines in the Hollywood — not to mention a cautionary tale of what not to do with a billion-dollar franchise.

Over the years, everyone from star George Clooney to writer Akiva Goldsman have apologized for just how bad the film ended up being. If you've ever subjected yourself to the painfully campy 125 minutes that is Batman & Robin, then you understand those apologies are indeed merited. If you haven't seen the film, just know that everything you've heard about how bad Schumacher's second and final Batman flick is are one hundred percent accurate.

As vocal as the cast and crew of Batman & Robin have been over the years, Schumacher remained relatively tight-lipped for a long time, never quite defending or condemning his most reviled film. That changed as Batman & Robin celebrated its 20th anniversary when Schumacher finally came clean about his own feelings for the film, ultimately apologizing to fans by stating, "I want to apologize to every fan that was disappointed because I think I owe them that." We wholeheartedly forgive you, Mr. Schumacher.

David Fincher — Alien 3

Of all the esteemed filmmakers that came of age in the 1990s, few are revered quite as much as David Fincher. With films like Seven, Fight Club, Zodiac and The Social Network to his credit, the director's reputation in Hollywood is all but unimpeachable these days. Still, Fincher's rep as an obsessive, visionary auteur was far from certain after his debut feature, Alien 3. In fact, many in Hollywood wondered if Fincher would ever get another gig behind the camera after that debut.

As it happens, Fincher wasn't supposed direct Alien 3. He landed the gig after a few higher profile directors left the project due to creative differences with 20th Century Fox. Fincher probably should've taken heed of that fact. For those unfamiliar with the story behind the filming of Alien 3, the production was marred by creative clashes between Fox and Fincher about everything from the script to the film's final cut. In the end, Fox reportedly locked Fincher out of the editing room, recut Alien 3, and released a muddled, murky version of the film that failed to connect with critics and audiences.

Though Alien 3 has gained more than a few defenders in recent years, it was initially viewed as an outright disaster for all involved. That includes Fincher, who has disowned the work altogether, stating simply, "A lot of people hated Alien 3. But no one hated it more than me."

Alan Taylor — Thor: The Dark World

Prior to stepping foot into the billion-dollar world of the Marvel Cinematic Universe, director Alan Taylor made a name for himself by working some of the best shows on television (including The West Wing, The Sopranos, Sex and the City, Deadwood, Lost, Mad Men, and Game of Thrones). He even scored an Emmy for Outstanding Directing for his work on The Sopranos.

With such an impressive résumé, it was no surprise that the folks at Marvel Entertainment were eager to bring Taylor on board for a project. Taylor's work on GoT seemed to uniquely qualify him for the fantastical, gothic realm of Thor: The Dark World, even if the project was bigger than anything he'd done before. With Marvel reportedly giving the director "absolute freedom while shooting," Taylor rose to the occasion. Or so he thought.

As with many big budget films, creative control often disappears once a studio has their film in edit. Per Taylor's comments about working on Thor, "The Marvel experience was particularly wrenching," because his creative input on The Dark World went by the wayside in the edit. He went on to claim that the studio's cut "turned it into a different movie," and that the experience is "something I never hope to repeat and don't wish upon anyone else."

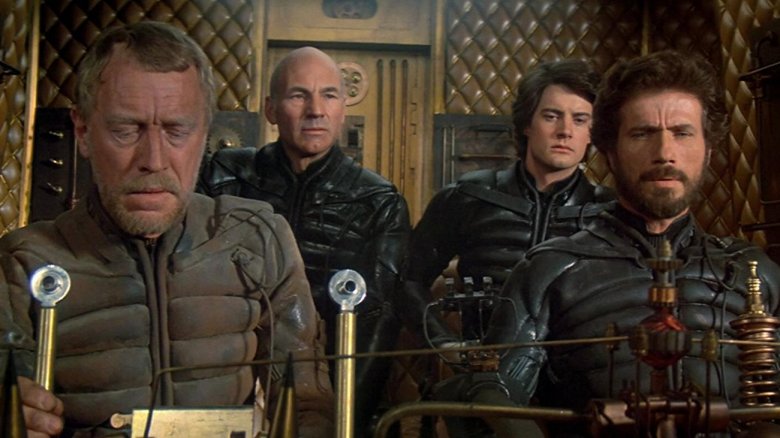

David Lynch — Dune

Post-production is where movies are made or broken. But sometimes a film just seems doomed before it even begins filming — like David Lynch's epic sci-fi misfire Dune.

It would seem all too easy to blame Lynch for Dune's shortcomings, but this is one of those cases where it seems anything that could go wrong with a film sort of did. Dune suffered through production struggles from scripting all the way through its final edit. If you've seen Dune, well, you understand how those struggles contributed to the film's quality ... or lack thereof.

Perhaps the biggest problem with Dune is that studio heads insisted on a maximum runtime of 137 minutes (so they wouldn't lose any screenings in theaters). If you know anything about Frank Herbert's Dune, you know that its dense, convoluted tale of interstellar power grabs, political maneuvering, and guerrilla warfare simply couldn't be told in that time.

Still, Lynch soldiered on and delivered a film that Roger Ebert called "a real mess." Over the years, Lynch has been quite candid about his feelings for Dune, saying he essentially "sold out" and admitting, "I probably shouldn't have done that picture." The fact that Lynch didn't have final cut on Dune certainly contributed that experience, and Lynch contends that the studio's condensing of Herbert's sprawling story "hurt it" in the end. We couldn't agree more — even if the film has become a bit of a cult classic.

Guillermo Del Toro — Mimic

Sometimes, it's not really the finished film that a director hates as much as it is the process of making it. That certainly sounds like the case for visionary director Guillermo del Toro and his English-language debut Mimic. After breaking out with 1993's arthouse horror flick Cronos, del Toro caught the attention of producer Harvey Weinstein, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Historically bad, that is. Mainly because del Toro and Weinstein were at loggerheads about the direction of the film before del Toro even had a finished script. As the director hadn't worked with a proper studio before, he lost pretty much every battle he picked with Weinstein, and by the time Mimic started filming, Del Toro admits he felt "condemned to doing the best giant cockroach movie ever made."

While the director might've achieved that modest goal, Mimic still isn't very good. While del Toro maintains that Mimic is "visually 100% what [he] wanted," and that it "has a couple of scenes" he's very proud of, he's also admitted that it's far from perfect.

In a recent interview he told reporters that he "really hated the experience" of working with Weinstein. He'd claim as well that his first American movie was almost his last, "because it was with the Weinsteins." Given the wave of disturbing allegations that've come out about Weinstein in the past year, we can't exactly claim shock at hearing he's also difficult to work with.

Arthur Hiller — An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn

Oscar Wilde once said that "Life imitates art far more than art imitates life." That quote may have been the basis for Arthur Hiller's 1998 Hollywood satire, An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn; though Hiller couldn't have foreseen how that statement would come to embody the film itself. Don't worry if you've never heard of Burn Hollywood Burn — not many people have. Just know that Hiller's sardonic tale of a first-time filmmaker's travails in the Hollywood machine is every bit the "spectacularly bad film" Roger Ebert claimed it to be in his zero-star review.

It's also a rather fascinating case of life imitating art. After all, the central character in the film is named actually named Alan Smithee, which was, for a long time, the name traditionally credited on a film when the real director no longer wanted his or her own name associated with it. That name, even the film's premise, still seems quite clever ... except Hiller made a truly terrible film himself. Even as the fictional Smithee struggled to get his name removed from the film within Hiller's film, Hiller soon found himself in the same spot. The director was so disappointed with Burn Hollywood Burn that he disowned the project before it was released, and even had his name removed. In the end, An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn actually credited Alan Smithee as director, which is the sort of biting ironic twist that even Hollywood couldn't have scripted.

Kevin Yagher — Hellraiser: Bloodline

As it happens, Hiller's Burn Hollywood Burn effectively ruined the pseudonym for future generations, and was in fact the last film to feature the Smithee credit. Lucky for Hellraiser: Bloodline helmer Kevin Yagher, Hiller hadn't yet spoiled the name when he ran into trouble on 1996's Hellraiser: Bloodline.

As Hellraiser fans no doubt recall, Bloodline was the ill-conceived franchise entry that took Pinhead and pals into space. It was also special effects guru Yagher's first turn in the director's chair on a feature film. When all was said and done, Bloodline would also be his last. That's not for lack of talent. By most accounts, Yagher came through with the goods on his one and only Hellraiser installment, delivering a cut of the film that, though deeply flawed, was considered by at least one critic to be an "ambitious, idea-filled exploration of the series' mythology." Unfortunately, the studio that funded the film disagreed.

The studio in question was Miramax's genre division Dimension, which means that none other than Harvey Weinstein was again meddling in a filmmaker's affairs — in this case, demanding that Yagher recut much of what had already been shot to make the film shorter and to feature more Pinhead. Yagher wouldn't have it, so Weinstein brought in Joe Chappelle to oversee extensive reshoots. In the process, Hellraiser: Bloodline became a completely different movie — one that Yagher (who hasn't directed a project since) refused to have his name on.

Michael Bay — Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen

It almost seems silly for Michael Bay to come out and trash one of his own films, mostly because so many critics have done a fine enough job of that without him. Still, as bad as many of Bay's films have fared with the critical set, they've generally played well with his Bayhem-obsessed fanbase.

While that fanbase turned out in force for Bay's 2009 Transformers sequel Revenge of the Fallen, the film didn't score well with many of them. It fared even worse with critics. In a surprising turn of events, Bay appears to be as big a critic of Revenge of the Fallen as anyone. In a 2011 interview, he openly admitted that "we made some mistakes" and added that the film was "crap."

While many viewers would likely agree with Bay's assessment, he offered a few interesting explanations as to why the movie turned out as badly as it did. First and foremost, the looming writer's strike played a major role in Revenge of the Fallen's narrative issues. With the studio rushing the project along in hopes of getting ahead of the strike, Bay went into production with little more than a 14-page outline of the film — and, well, shooting a film sans screenplay is hardly the framework for success. Though Revenge of the Fallen would pull in north of $800 million worldwide, it clearly remains a sore spot for the man behind the Bayhem.

Tony Kaye — American History X

No list of directors who hate their own movie would be complete without the epic tale of Tony Kaye and American History X. In the history of cinema, it's possible that no filmmaker has ever hated their own movie quite as much as Kaye hates this one; especially a movie that received such a warm critical reception. The film even earned an Oscar nomination for star Edward Norton. Of course, Kaye would hesitate to call the released version of American History X his own.

Norton himself is a big part of Kaye's problem with American History X. As the story goes, Kaye actually shot the film and delivered a rough cut to producers without problem. But then he spent over a year fine-tuning that cut, all the while fielding editing suggestions from Norton and his New Line Cinema bosses.

Eventually, those bosses got so fed up with Kaye's shenanigans that they kicked him out of the editing room. Then they brought Norton in to finish the final cut of American History X. Kaye responded by launching a smear campaign against Norton, New Line, and even the movie itself. He even tried to get his name removed from the film, but his efforts were all for naught — Norton's cut was released, Kaye is still listed as the film's director, and he may never really get over it.