HBO's The Wire: Inside The World Of One Of TV's Greatest Dramas Of All Time

If you like "The Wire," chances are you love "The Wire." The seminal 2002 HBO series, part of a cohort of influential shows that includes "The Sopranos," "Six Feet Under," and "Deadwood," doesn't have fans so much as it has defenders and evangelists. They will say that it is just as bleakly funny and emotionally devastating as "The Sopranos," and just as poetic in its own way as "Deadwood," and they are correct. Still, the show has never quite shaken the reputation that it's the Peak TV version of eating your vegetables: something you're supposed to do because it's important rather than something you want to do because it's fun.

While David Simon and Ed Burns' cop-drama-cum-treatise-on-the-American-experiment may not be a "fun" show in the traditional sense, it is far from a homework assignment. It is sprawling and novelistic in a way no television series had been before and few have been since, but also has a scene where a duck drinks whiskey. It is meticulously researched and bitterly cynical, but also stars a folk hero stick-up artist who strikes fear into the hearts of drug dealers by whistling "The Farmer in the Dell" down dark alleys. While the sheer number of subjects that the show is "about" — race, class, sex, violence, politics, addiction — can be overwhelming, the experience of actually watching the show is akin to settling in with a good book, full of characters who we love even when they're not doing their best. Let's take a look at the inside story of "The Wire," one of the greatest television dramas of all time.

Before the beginning

"The Wire" may have been a revolutionary take on the traditional cop genre, but it didn't come out of nowhere. In many ways, it was the culmination of Simon's life's work up to that point. A longtime reporter for the Baltimore Sun, he spent a year in the late 1980s embedded with the city's homicide division. The experience became the basis for his 1991 book "Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets," which was adapted by writer Tom Fontana and fellow Baltimorean Barry Levinson as the acclaimed NBC drama "Homicide: Life on the Street" in 1993. Simon wrote several episodes of the series himself, including the Season 2 premiere "Bop Gun," in which a grieving husband (Robin Williams) shames the detectives investigating his wife's murder for the gallows humor they use as a coping mechanism.

Fontana and Levinson decamped for HBO in 1997 with the proto-prestige prison drama "Oz." Three years later, Simon did the same with his 2000 miniseries "The Corner." Based on the book by Simon and cop-turned-educator-turned-writer Ed Burns, whom Simon befriended during his days with the Baltimore homicide unit, the six-episode series covers a year in the life of a family of addicts, who struggle to survive in a West Baltimore neighborhood where drugs are the only thriving business. In many ways, the series was a test run for the themes and topics that would be explored with more depth on "The Wire," and many of his collaborators would go on to work on subsequent Simon productions, such as co-creator David Mills and actors Clarke Peters, Reg E. Cathey, and Khandi Alexander.

Trojan horse

Cop shows have of course been a part of the landscape since the very beginning of television, and even earlier than that; Jack Webb's "Dragnet" was a radio show for two years before becoming one of the most iconic and influential TV series of all time. Detective shows have a tradition of presenting its cops in a heroic light — often partly to stay in the good graces of the real-life police departments who provide resources and technical consulting. While the snap of handcuffs on a perp's wrists may make for a satisfying narrative resolution, real life is never that simple, either for the police whose on-the-job traumas often manifest as addiction and violence, or for the citizens who view the police as an occupying force rather than a protective service.

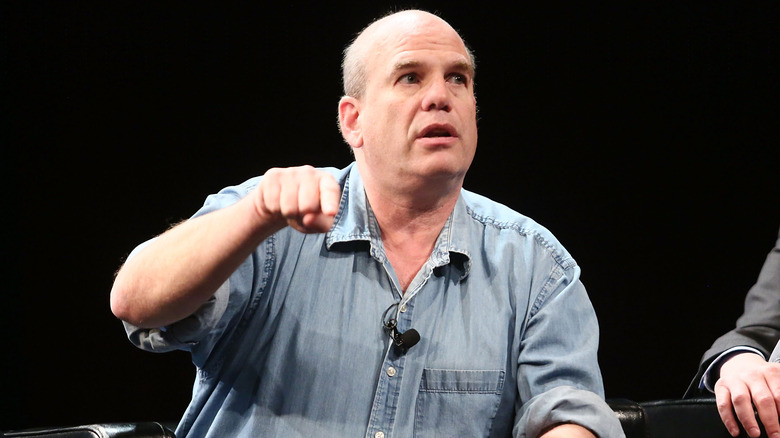

Simon and Burns understand both the warm comfort of fiction and the often demoralizing reality. "The Wire" uses that dichotomy to its advantage. Its cops-and-robbers routine was a Trojan horse hiding the show's true intent: An examination of decades of failed policies concerning policing and education, the pernicious influence of money on power at every level, and ultimately, the failure of capitalism itself. Crafting a great crime drama full of memorable characters was apparently dead last on Simon's list of priorities, to the point that he has seemed annoyed over the years that people do see it as a great crime drama full of memorable characters, as seen in a famously testy 2012 New York Times interview about the show's legacy.

True stories

Unlike "The Corner," "The Wire" is explicitly a work of fiction, but the plot of its first season is rooted in the real-life case that first introduced Simon and Burns to each other: The 1985 wiretap investigation of West Baltimore heroin kingpin Little Melvin Williams. Williams came up as a pool hustler and gambler in the 1960s and '70s, and by the early '80s was in the right place and time to become one of the city's biggest drug distributors, using a sophisticated system of pagers, pay phones, and coded language to move product and evade prosecution. Burns, then a homicide detective, was awarded a warrant to obtain information from those pagers — the first wiretap warrant of its kind in the country — and spent two years decoding Williams' system and gathering evidence in order to bring him down.

Williams (who would later have a small role on the show) was the clear inspiration for Avon Barksdale (Wood Harris); he even had a crafty, educated lieutenant, just like Barksdale's second-in-command Stringer Bell (Idris Elba). Elsewhere, Simon paid tribute to his friends and collaborators in different ways. The famous scene where McNulty (Dominic West) and his partner "Bunk" Moreland (Wendell Pierce) investigate a murder scene, communicating to each other with subtle variations of the f-word, is taken from a passage in Simon's "Homicide" book (per Brett Martin's history of the 2000s peak TV movement, "Difficult Men"). The character played by actor Delaney Williams was named after Simon's detective friend Jay Landsman, who also appeared on the show in a recurring role.

Casting across the pond

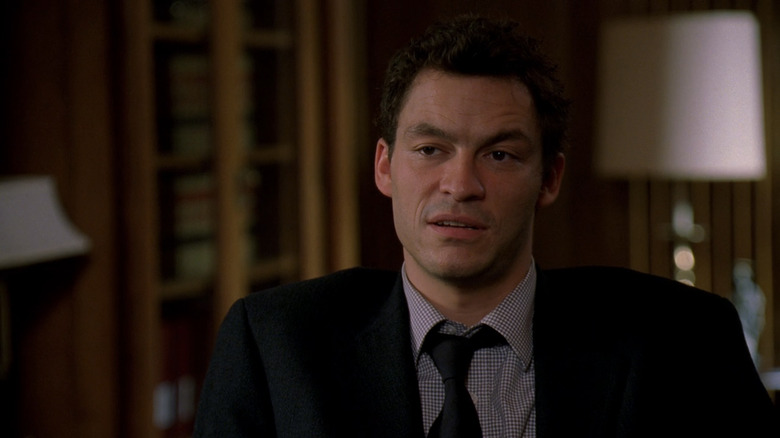

Jimmy McNulty (originally "McArdle" in Simon's show bible), the dogged, hard-drinking wreck of an Irish cop at the heart of the Avon Barksdale investigation, was a clear analogue for Ed Burns, though in "Difficult Men," Simon admits that McNulty's unstable personal life mostly came from his own experience. Originally the production had envisioned McNulty as an older detective, a veteran slightly gone to seed, and sought out British actor Ray Winstone. When they decided Winstone's American accent wasn't up to snuff, McNulty was reimagined as a younger man; Josh Brolin, John C. Reilly, and Liev Schreiber (whose brother Pablo would have a key role in Season 2) were all under consideration.

The role ultimately went to British actor Dominic West. Concerns that his native accent might pop out from under McNulty's "Bal'more" drawl were ultimately waved away. "Homicide" actor Clark Johnson, who directed the series' first three episodes, was particularly unconcerned: "I said, 'His accent sucks? Well, he came here from Dublin when he was nine and he's still got a trace of accent, so what?" he told Martin in "Difficult Men." "We'll make it work." West was not the only member of the original cast to hail from across the pond. Idris Elba was instructed by casting director Alexa Fogel to mask his cockney accent when auditioning for Stringer Bell. By the time Irish actor Aiden Gillen ("Game of Thrones") joined the cast in Season 3 as political striver Tommy Carcetti, however, any taboo against casting non-American actors had long since faded.

The writers room

Like the other HBO Davids, Chase ("The Sopranos") and Milch ("Deadwood"), Simon was both the creator of his show and its primary author, with a story credit on 50 of its 60 episodes and a script credit on 20 more. Burns' output was just slightly less, with story credits on 42 episodes and script credits on 10 more. But this was not a two-man operation, and Simon recruited writers whom he'd worked with on "Homicide" (Eric Overmyer, Joy Kecken, David Mills) as well as old colleagues from the Baltimore Sun (William F. Zorzi and Rafael Álvarez).

Simon also made the unusual move of recruiting crime novelists, which makes sense considering his ambition for the show to have the scope and structure of a novel. The first was D.C.-based writer George Pelecanos, who took on the duty of writing the penultimate episode of each season — usually the episode that had big, status-changing events, while the Simon-scripted finales would be more subdued. Boston novelist Dennis Lehane ("Mystic River") and writer Richard Price ("Clockers," "Sea of Love") both joined the staff in Season 3. The trio was respectful but also competitive, especially since Price, a generation older, had been a big influence on Pelecanos and Lehane. "Price was a guy we really looked up to," Pelecanos says in "Difficult Men." "But, having said that, I didn't want Richard to write a better script than I could."

On location

Armed with a cast that included Lance Reddick, Sonja Sohn, and Clarke Peters as keen-eyed detective Lester Freamon, the show was shot mostly on location in East and West Baltimore. Unlike the gritty streets of New York and Chicago, Charm City had little filmic history at the time. The city was mostly seen on screen in the works of two very different directors: Barry Levinson, who mined the nostalgia of his Baltimore upbringing in films like "Diner," "Avalon," and "Liberty Heights" (in addition to "Homicide"); and bad taste auteur John Waters, whose tales of multiple maniacs, cry-babies, and serial moms have become a point of civic pride.

Even a location as rough and ready as Baltimore needs a little movie magic now and again. Though the series was set on the west side of the city, filming largely took place in East Baltimore, where there were more vacant homes and fewer tree-lined streets. The Lafayette Courts housing project, where Little Melvin Williams had ruled his heroin empire in the 1980s, had been demolished by the city in 1995. To create "the Towers" — the Lafayette Courts analogue where the Barksdale crew is headquartered — production turned to a home for senior citizens. The building's lower floors were dressed to look like the projects, while additional stories were added to the top of the building via CGI.

Omar comin'

Even if creating memorable fan-favorite characters wasn't Simon's primary aim with the show, he was still very good at it. Every season, nearly every episode introduced some new major or minor character who arrived on screen fully formed, as if they had always existed, from knucklehead detectives Herc and Carver (Dominick Lombardozzi and Seth Gilliam) to confidential informant Bubbles (Andre Royo) and reformed thug Cutty (Chad L. Coleman) to unreformed Senator Clay Davis (Isiah Whitlock, Jr.). Standing above them all, shotgun in hand, is Omar Little, the legendary stick-up artist played indelibly by the late Michael K. Williams.

With his long duster, bulletproof vest, and fearsome facial scar, Omar was the scourge of small-time dealers across the city, an agent of chaos who, in his own way, was on the same side as McNulty and Bunk and the rest of the wiretap squad; he got to Stringer Bell before they did, after all. Omar was the role that put Williams, who overcame a tough Brooklyn upbringing (the scar was his own) to become an actor and filmmaker, on the map. It remained his best-loved role until his unexpected death in 2021. Amazingly, Omar is also based on a real-life person, Donnie Andrews, a Baltimore armed robber in the 1970s and '80s who, like Little Melvin Williams, became an anti-gang advocate later in life and was given a job on the show.

On the waterfront

After a first season spent following Omar and the Barksdale crew, Simon pivoted to another part of the city entirely for Season 2: the docks. And with that venue change came a slew of new characters, most notably union official Frank Sobotka (Chris Bauer), his nephew Nick (Pablo Schreiber), and his screw-up son Ziggy (James Ransome). Frank's desire to bring the failing harbor back to its former glory leads him to seek help from politicians and gangsters alike. When harbor cop Beadie Russell (Amy Ryan) uncovers a shipping crate full of dead sex workers, Frank finds himself caught between the police and the Greek mafia.

Season 2 is a turning point for the series, signaling that Simon's ambition was bigger than just the street corners in West Baltimore. By pivoting so early in its run, the show created a precedent for itself that allowed subsequent seasons to focus on city hall, the school system, and the newsroom without much pushback. However, the sudden change from the streets to the docks was a shock not just for critics and viewers (many of whom still consider Season 2 to be one of the show's worst), but for the actors as well. The number of minutes in a television season is finite, and a minute spent on a bunch of new, mostly white, characters is a minute not spent on established, mostly Black, characters. This fact was not lost on Williams, who was admittedly angry with Simon at what he saw as his character being sidelined.

Death around the corner

"The Wire," just like "The Sopranos," "Deadwood," and "Six Feet Under," played for keeps. Each series was about death in its own way, and there was never a guarantee that any character was going to make it to the end of a season alive. Since George Pelecanos was in charge of writing each season's explosive penultimate episode, he became a "grim reaper" of sorts, according to "Difficult Men," and the question of who was going to get the ax at the end of each season caused no small amount of anxiety in the actors.

This anxiety was compounded by the fact that Simon, by all accounts, was terrible at communicating with actors. This failing caused a bit of a problem in Season 3, when he and Pelecanos planned to end the penultimate episode with the death of Stringer Bell. The only problem is that no one bothered to tell Idris Elba this before he received the script. "I was pissed," Elba told the Hollywood Reporter years later. To Simon, Stringer's death was a thematic necessity. To Elba, though, it meant that he was getting fired. To make matters worse, the script originally had his killer, Omar Little, urinating on his body. Elba, already upset, flew into a rage at that particular detail, and it took Simon and Pelecanos removing it from the script to calm him down. On Elba's last day of filming, Simon took him for a walk and assured him that he had a long career ahead of him. Of course, Simon was right.

Season 4...

David Simon has a way with words, both on screen and off, but at the end of Season 3, he put his considerable rhetorical skills to work for an almost impossible goal: a fourth season. Season 3 had effectively concluded the Avon Barksdale saga and seemed like as good an ending as any, but Simon and Burns were adamant on a fourth season that would tackle the public school system, and a fifth season that would put print media in the spotlight. Simon pitched his fourth season to HBO president Chris Albrecht and executive Carolyn Strauss on the simple premise that there was more story to tell. Albrecht gave the go-ahead for Season 4; years later he joked to Brett Martin in "Difficult Men" that "I think it was easier to do the fourth season than to have to call up David and have another meeting."

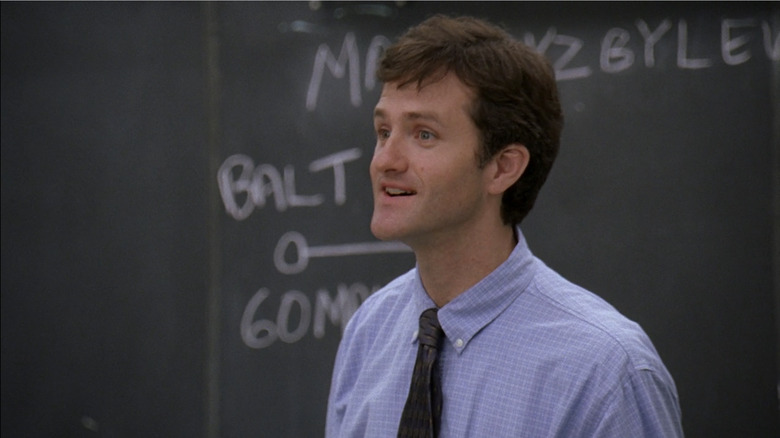

Saved from the brink of cancelation, Season 4 is widely considered not just "The Wire's" best season, but possibly the best season of television, period, a heartbreaking look at the way that the public education system is set up to fail its most vulnerable students. Based on Burns' experience as a seventh-grade public school teacher, the season focuses on disgraced detective "Prez" Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost), who at the end of Season 3 has left the BPD to become a teacher. His efforts to make a difference in the lives of his kids and be a role model are mirrored by the rise of psychopathic gangster Marlo Stanfield (Jamie Hector).

...and then Season 5

The critical response to Season 4 was enough to buy Simon and Burns a shortened fifth season. It had always been Simon's plan to use the final season as a critique of the newspaper business. "It was a critique of newspapers," he says in "Difficult Men," "but it was also a critique of the audience, of how stupefied and simplified the audience has become." As the season begins, the Baltimore Sun is going through another round of buyouts and layoffs; an opportunistic reporter (Tom McCarthy) latches onto a story about a serial killer prowling the streets of Baltimore. The only problem, though, is that there is no serial killer; the whole thing is an outlandish scheme by McNulty to divert funds to understaffed investigations, capitalizing on the panic (and funding) that news of a serial killer brings out.

Despite usually finding itself on or near the bottom of any seasonal ranking, Season 5 was well-received by critics, even if it didn't hit the astronomical heights of Season 4. Simon, however, seemed to take any indication that the serial killer plot was outlandish, or that the newspaper storyline was too inside baseball, as a personal affront. A week after the final episode premiered in 2008 he penned a bitter missive on the Huffington Post, more or less accusing critics and audiences of not adequately understanding the season. Four years later in the New York Times, he was still beating that drum, grumbling about shallow-minded fans who came to the series late.

Way down in the hole

"The Wire" was famously overshadowed in popularity by HBO stablemate "The Sopranos," and infamously overlooked by the Academy; in five seasons it only received two Emmy nominations, both for writing. But critics like Alan Sepinwall had already crowned the show a landmark in American television after Season 3, and its esteem and influence have only grown since then. Its depiction of queer Black characters like Omar and Sonja Sohn's detective Kima Greggs helped open the doors for further representation in the decades ahead. Any show of the streaming era that has pitched itself as a "10-hour movie" owes a debt of gratitude to "The Wire's" innovations in long-form serialized storytelling.

Among other rewards, like far more money than he ever would have made as a newspaperman or novelist and a Macarthur Genius Grant, the show gifted Simon with a number of lifelong collaborators. Ed Burns and George Pelecanos, together or separately, have been on board with every Simon-helmed project since, including "Treme," "The Deuce," "We Own This City," "Generation Kill," "Show Me a Hero," and "The Plot Against America." Wendell Pierce, Clarke Peters, and Khandi Alexander from "The Corner" starred in "Treme," a sprawling look at the lives of musicians and service workers in NOLA in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, while Simon still holds out hope that one day he and Idris Elba will work together again. Together, these artists made a lasting impact on American culture. Fifteen years after it ended, "The Wire" remains the standard bearer for mature, uncompromising, socially conscious television.