Wakanda Forever Doesn't Have Too Many Endings (& Neither Does The Return Of The King)

The MCU is full of countless stories. Some of these are one-off events, like "Black Widow." Others are lengthy narratives unto themselves, as is the case with Thor's quartet of films. Still others are massive crossover events, like "Avengers: Infinity War" and "Avengers: Endgame." Don't forget the serialized Disney+ spin-offs, too. Most MCU stories, though — especially the theatrical films — tend to be lengthy affairs. The long movie format, in particular, is a unique experience. It stretches out over enough time to prompt fans to caffeinate heavily before late-night showings and strategically plan their bathroom breaks.

"Black Panther: Wakanda Forever" is a good example of an MCU film that drew criticism for its length. Some would say that the movie's 161-minute run time is an exorbitant requirement to tell a single story. Others take issue with the number of "endings" in the film as particularly obnoxious (It's over, right? Oh, wait, nope. There's one more scene ... and another ...)

This particular criticism is reminiscent of another famous fantasy film: "The Return of the King." The theatrical version of Peter Jackson's award-winning conclusion to the "Lord of the Rings" film trilogy is 201 minutes long (nevermind the roughly 250-minute extended edition). Couple that with the film's near-infinite string of endings, and it's easy to see how both movies have gotten a bad rap for their failure to finish strong. Admittedly, this multi-ending format is frustrating at times — especially when a viewer hasn't had a bathroom break in nearly three hours.

But do bladder-based frustrations and petty annoyances born out of exhaustion mean having several endings to a movie is inherently bad? On the contrary, there's a solid case to be made that longer, multi-ending films don't have too many endings. In fact, they may have too few.

The many endings of Wakanda Forever

"Wakanda Forever" is such a massive film that it's hard to believe it takes place within a single franchise. The movie's sprawling cast of characters and global scale give it more of an "Avengers" feel than anything else. And yet, as the story plays out, it remains distinctly loyal to the Black Panther franchise. Sure, there are some crossovers like Riri Williams (Dominique Thorne) and Valentina Allegra de Fontaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus), but by and large, the bulk of the cast is all specific to the Black Panther universe.

Still, the huge number of characters involved leads to a lengthy string of ending scenes as the movie gradually comes to a close. For instance, after the climactic fight on the high seas (and nearby shores), where Shuri (Letitia Wright), the new Black Panther, defeats Namor (Tenoch Huerta), we see Riri return to MIT, just in time for her own spin-off. M'Baku (Winston Duke) becomes the new king of Wakanda. Namor and Namora (Mabel Cadena) sort through the emotional and political ramifications of their humbling at the hands of the Wakandans. Okoye (Danai Gurira) saves Ross (Martin Freeman) on his way to prison. Oh yeah, and as the credits roll, Shuri meets her nephew, T'Challa's son.

It's a constant roll of endings, for sure. The way fans count "endings" is a bit subjective, to be fair, but overall, there are around five of them before the film officially ends. This can take viewers by surprise if they're expecting a quick, traditional wrap-up once the main climax of the movie is over.

Now, let's see how "The Return of the King" compares.

The Return of the King has a lot of endings, too

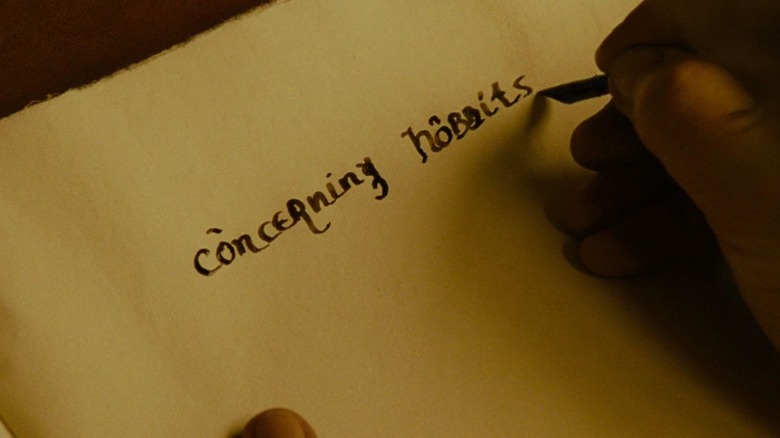

J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth is a rich and vibrant place. Amazon's "The Rings of Power" series is set thousands of years before "The Lord of the Rings," and even then, it barely touches on the world's earlier histories. Even within the confines of the "Lord of the Rings" trilogy, there are a ridiculous number of protagonists, antagonists, and storylines littered everywhere.

These start small in "The Fellowship of the Ring" and then fan out as the titular company of heroes is formed. By "The Two Towers," the group splinters, as does the story, and it doesn't come back together until the end of "The Return of the King." At that point, there are still a lot of characters alive and well, and the narrative takes the time to give all of them — or at least most of them — some sort of closure.

This starts right after the One Ring is cast into the fire via a Gollum-shaped conduit. Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin) are saved in the nick of time by Gandalf (Ian McKellen) and the Eagles. Frodo wakes up in the Houses of Healing, where he's joined by his friends. They attend the coronation of Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) shortly after that. Arwen (Liv Tyler) shows up and joins her betrothed. From there, we see the Hobbits arriving home in the Shire (believe it or not, this skips like a dozen other endings in the book). Sam hooks up with Rosie Cotton (Sarah McLeod). Frodo writes his memoirs (along with Bilbo's). The Hobbits head to the Grey Havens, where Frodo and Bilbo (Ian Holm) sail off into the West. Sam returns home. And that's it. Again, by our count, that's nine endings. Yeah...

The case for too many endings

Okay, so "Wakanda Forever" has five endings and "The Return of the King" has nine endings (again, subjectively speaking). These are a lot to take in, especially at the end of each film's emotional rollercoaster of a storyline. The question is, are they justified? Is there a good reason to ask viewers to sit through so many endings, or is it just an off-the-rails writers' room or an ambitious director trying to cram everything into a truncated cinematic adaptation?

We'd like to posit that, often, the presence of too many endings is neither of those things. Instead, it's often proof positive of the worthiness of a story to be told in the first place. Let's explain.

"The Return of the King" is an iconic, beloved, and extensive story. Tolkien himself said in the foreword to "The Fellowship of the Ring" that the primary motive for writing the story was, in his words, "the desire of a tale-teller to try his hand at a really long story that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them, and at times maybe excite them or deeply move them." Most would agree that the Oxford professor succeeded in this self-appointed challenge. "The Lord of the Rings" is a superbly captivating story that is worth every second of the experience.

While it doesn't have as rich of a history as "The Return of the King," though, "Wakanda Forever" can also make its case for multiple endings. It was born out of a tragic and compelling set of circumstances, surrounding the unexpected passing of Chadwick Boseman. This generated a powerful creative dynamic, clearly visible both on-screen and behind the scenes. The entire movie has something to say, and it's dripping with deeper meaning.

The right to tell a good story ...in its entirety

Both "The Return of the King" and "Wakanda Forever" feature powerful narratives that are tested by time and the trials of life, respectively. This gives both films a special duty to deliver their stories well — regardless of the specific form or length of time that might take.

Now, to be clear, this isn't a license to drone on or use storytelling techniques that aren't appropriate for a cinematic format (more on that second one, in a minute). Nevertheless, stories as grandiose as these ones do require time to tell, and that includes the ending. So many characters are involved, each with their own skin in the game, that it would be an injustice to leave the "less important ones" unresolved in the name of a quick, clean ending designed to put a bow on top of the whole ordeal.

The stories that have something to say deserve enough runway to stick the landing. If "Wakanda Forever" needs five endings to provide closure and set the stage for the next stories in the franchise, so be it. If "The Return of the King" requires nine ending moments (and even more in the source material) to properly bring closure to its catalog of characters, that's okay with us.

Does this mean every story with a dozen endings is worthy of its multi-faceted finale? Nope. Not by a long shot. There are plenty of examples of creatives riding high on their own project's self-worth only to botch the landing with overly-extended endings. However, when there are clear, universally approved reasons for a story to exist, there's a good chance that it will also get an extra degree of grace as it spends additional time wrapping things up.

A counterpoint: satisfying the viewer

Before we go, there is one counterargument that deserves some attention, namely this: the natural format of a movie doesn't typically work with an excessive number of endings. To put it another way, movies aren't books (either of the novel or comic variety). You can put a printed form of entertainment down and go to the bathroom without missing anything. In fact, you can even bring it right along with you. On top of that, books can be consumed in multiple sessions over weeks and even months, whereas movies suffer when they're overextended or fractionalized.

When a viewer expresses discontent because they're exhausted or frustrated with the end of a long, drawn-out movie-watching experience, they're justified too. Each moviegoer has their own expectations, and they should absolutely be part of the litmus test of whether an attempt to tell a story is successful or not.

Even then, though, we quickly arrive at an impasse. On the one hand, die-hard fans (the loudest audience and the one that keeps these franchises alive) typically can't get enough storytelling. They'll eat up any number of endings as they seek emotional resolution for their beloved characters and piece together the larger stories. On the other hand, casual viewers are easily exhausted by the excessive ending trope. They're not as invested as the die-hards, and at the end of the day, it's the volume of their patronage that makes these movies possible in the first place.

It's a hard line to walk, telling a good story and keeping viewers of all kinds happy. Few have pulled it off successfully. And yet, it doesn't change the fact that good stories deserve to be told in full — even if it takes half a dozen endings or more to do so.