Films That Got The Future Spectacularly Wrong

As anyone who has gazed furiously into a crystal ball will know, predicting the future is hard work. Prophecy has never been what you might call an exact science: It takes blood, sweat, tears, and a fair bit of outlandish imagination to see even the bare bones of what things will look like 10, 50, or 100 years from now. However, this hasn't stopped intrepid filmmakers from stamping their vision of the future on the big screen in a host of sci-fi movies. Oftentimes, this goes well. Films such as "The Truman Show," "Minority Report," and "Lawnmower Man" all contain elements like reality TV, targeted advertising, and VR headsets, which have become staples in the modern world.

Yet most movies set at some distant point in the future veer pretty wide off the mark. Cinematic accounts of humanity's future also tend to be dystopian, rather than utopian. They're typically set in the grim aftermath of a terrible catastrophe, feature totalitarian regimes and barbaric forms of entertainment, and nearly always involve people doing terrible things to one another. Things certainly aren't perfect, but this overwhelming negativity doesn't accurately represent the way things have turned out to be. Which films got the future spectacularly wrong? We're here to find out.

Soylent Green

Released in 1973 and set in 2022, Richard Fleischer's "Soylent Green" tackles soaring population levels. Yet as the plot thickens, the viewer is left with a plate of something extremely unsavory to digest. Nearly everyone in this film's New York City is starving and living cheek-by-jowl in abysmal conditions. The only thing that saves the Big Apple's citizens from starvation is their daily dose of a wonder protein called Soylent Green. As other food sources have presumably run out, Soylent Green is hailed as the nutritional savior of mankind. But is it?

According to official sources, Soylent Green consists of plankton harvested from the ocean. But when one of his top guys is murdered, curious cop Robert Thorn (Charlton Heston) smells something fishy. He starts digging with the help of his professor friend Sol Roth (Edward G. Robinson). Before long, the deductive duo discovers that the dying oceans haven't been a viable source of the plankton used in Soylent Green for years. The real ingredient being added to the mix is dead human flesh. This grim truth leads Thorn to shout the memorable line, "Soylent Green is people!" 2022 has come and gone, and although some insanely terrible things took place, we have yet to resort to cannibalism to survive.

Logan's Run

The modern world is obsessed with reversing the aging process. Growing old is treated by many as something to be avoided, or at least kept behind closed doors. This can be toxic — but at least we haven't started to euthanize people on their 30th birthday. In Michael Anderson's 1976 film "Logan's Run," human civilization has ended up in that dark place. Wrinkles, grey hair, and hip operations may be a thing of the past, but so is long life, maturity, and hard-won wisdom. Set in the year 2274, the people of "Logan's Run" live in a domed city ruled by an all-powerful computer. Everyone appears to live a life rich in pleasure and leisure. However, there is a catch. Due to the threat of overpopulation, everyone must participate in a "renewal" ritual called "Carrousel" on their 30th birthday.

Although it may sound like a Botox treatment, the rite of Carrousel actually vaporizes each participant. There is no escape from it, as the city's inhabitants are chipped with a crystal that flashes as they approach their last decade. Those who attempt to run away are chased down by the city's police, known as the Sandmen. But Sandman Logan (Michael York) manages to flee the city and discover an elderly man amid the ruins of once-great cities. Modern people might be youth obsessed, but at least we know there literally is life after 30.

Death Race 2000

Although many in the modern world are attempting to break away from fossil fuels, filmmakers often envisage a future where gasoline-fueled automobiles continue to rule the roost. The Earth may die, society may collapse, and man's inhumanity to man may scale new and giddy heights, but precious resources keep burning, because we've got to get around. Paul Bartel's 1975 film "Death Race 2000" is a great example. Set at the dawn of the current millennium, it takes place in the aftermath of a huge economic and civil crash that plunged America into totalitarianism. The public's one joy is the annual Transcontinental Road Race.

This is no Le Mans: Drivers kill pedestrians for bonus points as they blaze a trail to the finish line. They also have catchy names, such as Nero the Hero (Martin Kove), Calamity Jane (Mary Woronov), Machine Gun (Sylvester Stallone), and Frankenstein (David Carradine). These colorful characters drive highly modified cars that reflect their personalities. But 2000's race is doomed to be the last, because a resistance group plans to sabotage it in a bid to ignite a regime change. "Death Race 2000" explores our fetishism of the car as both a symbol of personal freedom and self-destruction. It's also a futuristic and darkly humorous take on Juvenal's famous reflection that all a contented public needs are "bread and circuses." Thankfully, the modern public confines their lust for vehicular carnage to video games.

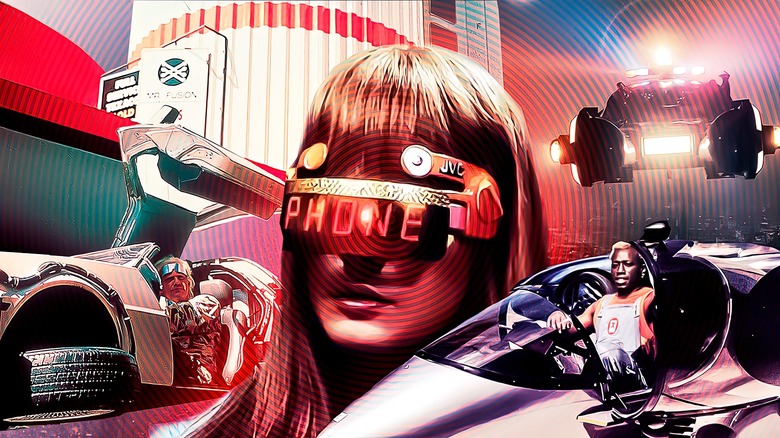

Back To The Future Part II

Although "Back to the Future" serves up a rose-tinted version of 1950s America, it's mostly accurate. Predicting the future, however, is a completely different ballgame. Get it right, and people will call you Nostradamus. Get it wrong, and people will have a good laugh at your expense for years to come. Released in 1989, Robert Zemeckis' "Back To The Future Part II" is set in 2015. It confidently predicts a completely different world to the one we all came to know after the clock struck midnight on December 31, 2014.

The movie's flying cars and hoverboards now make us roar in mirth. The outdated and outlandish fantasy of it all is, ironically, intensely '80s. Even worse, Marty McFly's 2015 features eyewear with a Google Glass vibe ... but no internet or mobile phones. Huge oversight. To the film's credit, it does anticipate automation and biometrics. But we've definitely not gotten to enjoy 17 "Jaws" movies. It also gets fashion all wrong: Who among us sports double-ties, gold raincoats, vests that come equipped with sound effects, sneakers with self-tying laces, or, best of all, self-drying and size-adjustable jackets? It's all pretty goofy, but we can't be too hard on "Back to the Future Part II." Its video calls are eerily prescient, given our modern use of Zoom.

2001: A Space Odyssey

When Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon back in 1969, he ripped up the rules of what was possible. To many people in the '60s, it suddenly seemed logical to expect commercial space travel to become as accessible as a local taxi service by the year 2001. Stanley Kubrick imagined this sort of future a year before the Moon landing in his science fiction classic, "2001: A Space Odyssey." However, despite predicting a world governed by technology, Kubrick's magnum opus fails to get the future right. As the likes of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk have proved, space travel is still the preserve of the elite.

Moreover, though there are tablet-like devices in the movie, nobody owns a personal or portable computer. This makes sense: In the 1960s, computers were so bulky and expensive that the thought of nearly every household owning one was more fanciful than men landing on the moon. Still, in HAL 9000, Kubrick does a pretty good job of predicting the rise of artificial intelligence. Suspended animation and mass colonization of the moon have yet to become a reality, though. This is no skin off Kubrick's nose: He did such a grand job painting a postcard-perfect picture of what space looks like, conspiracy theorists have claimed that he helped fake the actual moon landings.

The Running Man

The Earth is being stripped and sickened, corruption is commonplace, and injustice is rife. What keeps us all apathetic towards our plight? According to director Paul Michael Glaser's 1987 film "The Running Man," it's reality TV. This film is set in the U.S. of 2017, where a lack of food and natural resources has led to dystopia. To escape the harsh and unforgiving reality of everyday life, viewers tune into a highly popular game show in which criminals can get their sentences erased by fighting for their lives before a titillated audience.

"The Running Man" gets a lot of things right, like fake news, deep fakes, voice-activated household appliances, a dizzying abundance of flat screen TVs, and militaristic levels of airport security. It also gets a lot of things wrong, such as fitting prisoners with explosive collars and the continued use of cassette tapes and corded phones. The biggest thing "The Running Man" gets wrong is its central theme. Modern audiences may watch things like "The Hunger Games" and "Squid Game," which explore gory game shows. But these productions specifically frame such entertainment as depraved and unethical. We haven't yet returned to eagerly watching gladiators battle to the death — though we do like fiction that presents such a possibility as a ghastly warning.

Demolition Man

1993's "Demolition Man" begins innocently enough in the year 1996. But soon, policeman John Spartan (Sylvester Stallone) and hardened criminal Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) end up in a prison that puts convicts in suspended animation in the name of rehabilitation. Spartan and Phoenix wake up in 2032 to attend a parole hearing and find themselves in a Californian megalopolis called San Angeles. The good news is, violent crime has been all but eradicated. The bad news is, that makes the future easy pickings for a criminal like Phoenix. He has a field day killing people who don't how to fight back. Realizing it takes a wolf to catch a wolf, the authorities set Spartan on his path.

Watching Stallone and Snipes go toe-to-toe on the big screen is doubtlessly entertaining. Even more intriguing is the notion that all violent crime and bad behavior will be a thing of the past in 2032. But let's be honest: San Angeles is a pretty sterile and infantile place. Sports, sex, swearing, alcohol, and meat have all been outlawed, and citizens are treated more like cattle than humans. Denial of choice is not progress. But "Demolition Man" knows this: Its vision of the future is a warning that the road to hell is always paved with good intentions. It's not likely to come to pass, and we're thankful for it.

Planet of the Apes

Franklin J. Schaffner's "Planet of the Apes" doesn't monkey around: Its take on both Darwinism and the creation story is spectacularly different. Astronaut George Taylor (Charlton Heston) washes up on a strange planet where apes not only talk, they've enslaved humanity. These fearsome primates live in complex and intricate societies teeming with religious, scientific, artistic, and intellectual pursuits. Like most civilized creatures, they're capable of acts of great cruelty to any species that isn't their own. But the film lands an iconic final sting when Taylor finds the Statue of Liberty in pieces on the beach. Realizing he's traveled to a future Earth ravaged by nuclear war, he falls to his knees and howls in horror. Humanity was at fault all along.

As a movie, "Planet of the Apes" definitely works — but as a prediction of the future? Not so much. Although the threat of nuclear war is more present than ever, we can't help but wonder if apes would be any better at surviving the fallout than humanity. Additionally, a 2016 study revealed that the average human brain is three times greater in mass than a chimpanzee's. Moreover, our cerebral cortex boasts double the amount of cells. Earth isn't likely to become a planet ruled by any apes besides humanity any time soon.

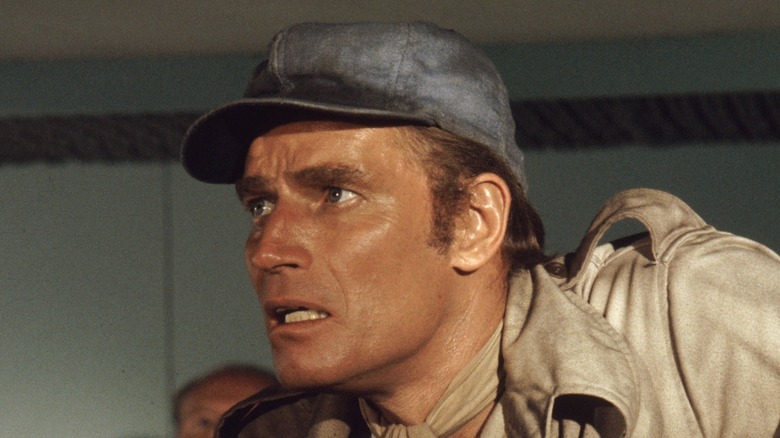

Escape from New York

1981's "Escape from New York" is a poignant reflection of its era's jadedness. The film is set in 1997, in an America at war with both China and the Soviet Union. The country is also fighting a never-ending tidal wave of crime. To cope, Manhattan Island is turned into a massive prison. No one gets in or out of this maximum security complex, which is unapproachable by water or land. But en route to a peace summit, the president's plane is hijacked. His escape pod lands squarely in this hotbed of crime and inequity.

Cocky convict Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) is sent in via stealth glider to rescue the president from the clutches of a crime lord known as "the Duke" (Isaac Hughes) and his menacing minions. From here on out, it's all action, bravado, and one-liners as Snake slithers around Manhattan in a demented bid to keep the president safe. Released before cyberpunk was really a thing, "Escape from New York" would prove extremely influential. At the time, it even seemed like a logical conclusion to the mean New York streets depicted in films like "Taxi Driver" and "Superfly." Fortunately, the Big Apple cleaned up its act by the time 1997 rolled around. Instead of becoming a prison, Manhattan became a very desirable place to live.

Blade Runner

1982 classic "Blade Runner" is set in 2019 Los Angeles, where everything is manufactured and manipulated by unregulated corporations — even human beings. The technology is cutting-edge, glittering, and intense, and humanity is in danger of losing its soul and moral compass. To help it regain its way, former cop Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) hunts down a gang of replicants who look and act human, but are in fact bio-engineered humanoids.

"Frankenstein" for the cyberpunk age, "Blade Runner" is set in the future, but at heart, it's a study of what it means to be human and how greed, technology, and corporate interests trample our finer sensibilities. When Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) says, "I've seen things you people wouldn't believe ... All those moments will be lost in time like tears in rain," it's impossible not to feel his pain. Nevertheless, "Blade Runner" falls way short of being an accurate prediction of 2019. Flying cars, off-world colonies, and humanoids capable of independent thought and action just aren't around yet. Plus, Atari and Pan Am are definitely no longer huge commercial concerns.

The Terminator

Humans have something of a love-hate relationship with technology. We'd be lost without our smartphones and computers, but we also have grave concerns about artificial intelligence. One minute we're chilling with Netflix — the next, we're eyeing Alexa with increasing paranoia. To date, machines have generally served our best interests. But this doesn't prevent us from harboring long-held suspicions that given the right opportunity and circumstances, the machines might turn on us like an army of serpents.

Released in 1984, James Cameron's "The Terminator" plays effectively on this deep-rooted fear. When 2029 resistance fighter Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) travels back in time to rescue Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) from being murdered by a cybernetic killer (Arnold Schwarzenegger), we all nod our heads sagely. When we learn that Sarah Connor's unborn son John will lead the resistance against a rogue computer system called Skynet, it makes sense. But ask yourself this: Has any machine independently attacked you, ridiculed you, or gone out of its way to make your existence unbearable — let alone cause genocide on a mass scale? "The Terminator" is a great film, but it gets our computer friends and the future all wrong. Just ask Siri!

2012

Ronald Emmerich's 2009 disaster flick "2012" doesn't hold out much hope for humanity's future, particularly for those living in poverty. In a world where the ice caps are melting, the sea levels are rising, the sun is heating up, and the magnetic poles are shifting, some lucky people are secretly offered once-in-a-lifetime tickets to board one of nine arks. Each ark will ferry 100,000 individuals far away from the impending apocalypse and global flooding. The problem is, these tickets cost $1 billion per person. This price tag puts the tickets out of reach for struggling father of two Jackson Curtis (John Cusack). But, through a series of surprising events, Curtis unearths the ark conspiracy.

Warnings of ecological crisis and impending doom are hammered home in "2012." Yet, despite what various interpretations of the so-called Mayan doomsday calendar suggested, the world didn't end in 2012. If any film about the future is handicapped by its title, it's this one. "2012" is driven by events as opposed to characters, which means it doesn't really bear re-watching. In fact, watching "2012" may make you wish the whole apocalyptic process would speed up by 158 minutes or so.